A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

By ROBERT LOERZEL

Photographs by Robert Loerzel (except historic images)

(Jump ahead to the TABLE OF CONTENTS)

INTRODUCTION

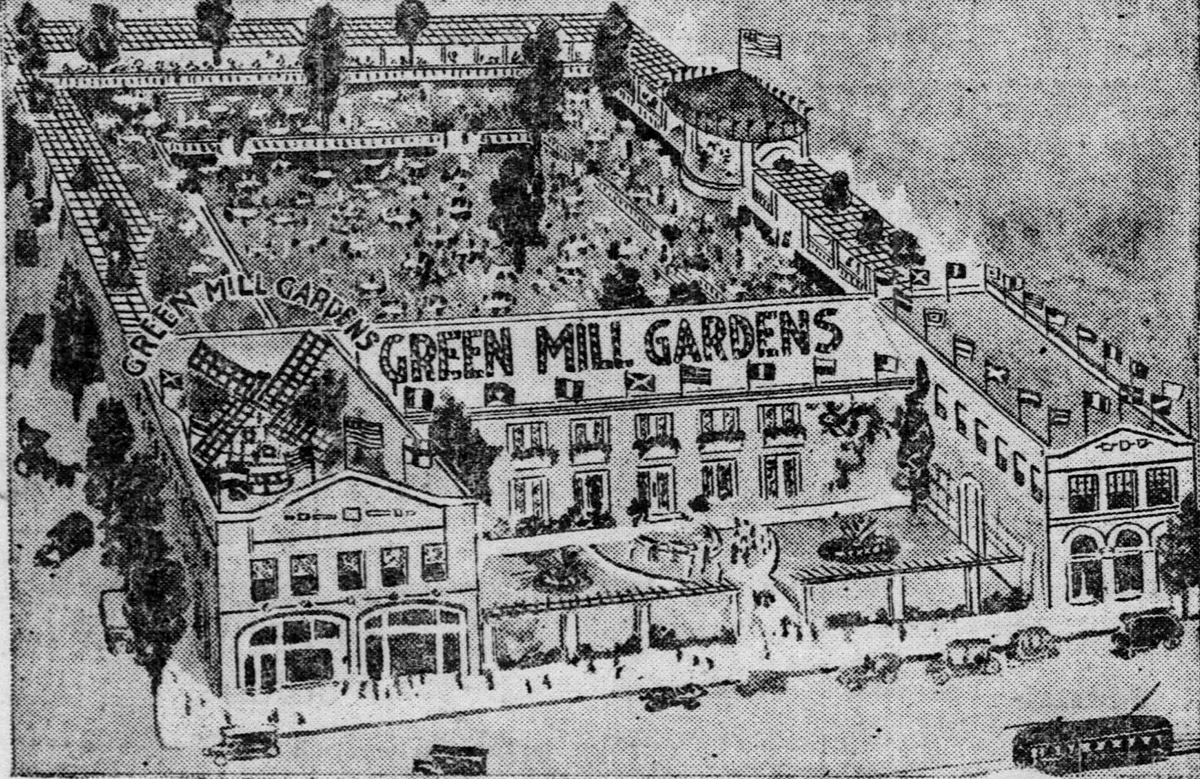

When Green Mill Gardens opened in June 1914, an advertisement called it “the coolest spot in Chicago.” That was surely just a reference to the temperature in the sprawling complex’s “sunken” outdoor area, where visitors were promised an “evening in comfort and pleasure in a delightful spot encircled by a terrace of flowers and climbing vines.”1

It wasn’t until years later—after World War II—that the African American expression “cool” was popularized by bop musicians, becoming a term of the highest praise.2 The word’s precise meaning is ever elusive, just like the mysterious qualities that make something cool. Whatever “cool” signifies, the Green Mill’s still got it. Lots of people (including me) think so, anyway. But of course, “cool” is in the eye and ear of the beholder.

For a very long time now, the place has been called the Green Mill Cocktail Lounge, a name spelled out in neon letters amid the blinking lights above the entrance. It’s at the same street corner where it all started—just northwest of Broadway and Lawrence Avenue, the heart of Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood—but the venue is far smaller than it was in those early days. It’s tucked inside what remains of the original Green Mill Gardens building (which was enlarged, reconfigured, reduced, damaged by a fire, and rebuilt).

(Photo: Chicago History Museum, DN-A-0821, Chicago Daily News, 1933. I recently asked the Chicago History Museum if it had any photos of the fire at the Green Mill building in 1933, and the archives staff found some glass negatives, which had never been scanned—until I requested them. This is one of those photos.)

If the Green Mill isn’t the coolest spot in Chicago today, then it’s certainly a strong candidate for that distinction. It’s also one of the best places anywhere to see live jazz. I consider myself lucky to live just a few blocks away. No matter how many times I’ve stepped through that door, I still marvel at the sensation that I’m entering a nightclub from a bygone area.

The joint hasn’t been redecorated for decades, and I hope it never will be. The walls are encased in wood, and not just basic wood paneling. The L-shaped room resemble like a giant piece of furniture. Large light fixtures on the ceiling look something like upside-down tables.

At places, the woodwork on the walls opens up to reveal large paintings of rivers and lakes. These landscapes are surrounded by elaborate wooden curves, but those aren’t exactly picture frames—they’re actually part of the wall. Red lights shine on these idyllic aquatic images, practically obliterating whatever colors were on the artist’s paintbrush. Everything just looks red.

At the back of the room, behind the stage, one of these openings in the wall shows a dark red curtain instead of a painting. (A curtain inside a wall? If it ever opened up, what might it reveal? Surely, just another wall—but the imagination wanders…) Hanging in front of this curtain, cursive neon letters spell out “GREEN MILL” in an appropriately green glow. The juxtaposition of red and green should evoke Christmas, but the colors clash and mix here in stranger ways.

A sculpture of Ceres, the Greek goddess of the harvest, holds a bundle of fruit in a back corner, standing behind an organ and a pile of musical gear. Naked from the waist up, she’s lit from below, like a monster in an old movie, with blank eyes that seem to stare blindly out at the Green Mill’s audience (including people young, old, and in between, some of them casually dressed in jeans and T-shirts, some of them decked out in snappy suits and dresses).

Musicians call the statue Stella, alluding to an old jazz standard.3 “That great symphonic theme / That’s Stella by starlight / And not a dream / She’s all of these and more / She’s everything that you’d adore.”4 A life-size cardboard cutout of the late Chicago saxophonist Von Freeman peeks over Stella’s shoulder.

Dave Jemilo, who has owned the Green Mill since 1986, often serves as the emcee, standing near Stella as he introduces bands at the beginnings and ends of all three sets, making sure to say each musician’s name. Jemilo is the Green Mill’s official shusher, imploring his customers not to talk whenever musicians are playing. And when people do talk, I’ve heard him command them to “shut it.”

In his own gruff way, Jemilo demonstrates enthusiasm for the music. “You guys are lucky sons of bitches—there are two sets left,” he said one night in 2022, after the Makaya McCraven Quintet had finished its first set. After a set by the Flat Five in 2016, Jemilo picked up his microphone and declared: “That’s the Flat Five. How about that shit?”

On another occasion, he took the night off from work, but showed up anyway, to see a performance by Green Mill regulars Joel Paterson, Chris Foreman, and Greg Rockingham. “If I didn’t own the joint, I’d be here to hear it,” Jemilo remarked, after he happened to sit down next to me at the bar.

Behind the bar sits a Hammond B3 organ (a classic made-in-Chicago instrument), which Foreman plays during an early set every Friday evening. On other nights, Green Mill employees sometimes stand next to the organ’s wooden cabinet, using it as a sort of desk. A framed photo of Al Capone used to sit atop the organ, but I haven’t seen it lately.

Signs taped to the bar’s mirrors declare, “CASH ONLY,” and all of the money goes in and out of old-fashioned cash registers. Amid the rows of liquor bottles, a statuette of a woman holds an illuminated globe aloft, Earth encircled by a Schlitz ribbon. There’s a trap door in the floor behind the bar, where bartenders can occasionally be seen descending into the Green Mill’s famous subterranean storage area to retrieve supplies.

Near the Green Mill’s entrance, a large painting hangs in front of the mirror, depicting some of the legends about the joint’s early history. Al Capone is shown, sitting at a table. I’ve overheard Green Mill customers regaling their friends with tales about Capone sitting in a particular booth or escaping through a network of tunnels.

I started digging into the history of the Green Mill around 2006, when I moved to Uptown. At that time, the Green Mill’s website said the place originally opened in 1907,5 so I thought I might write an article about its hundredth birthday.

But as I learned more, I came to doubt whether it really had begun in 1907. And I began questioning other stories that are often told about the Green Mill’s early years.

The Green Mill is an object of endless fascination, and many people have written about. If you’re looking for stories about the Green Mill in recent decades—the era since 1986, when Jemilo took over—I recommend Patrick Sisson’s Chicago Reader article “An Oral History of the Green Mill.” But I was more interested in exploring the early era, when this place was Green Mill Gardens. How many of those stories about the Prohibition Era are true?

One day in December 2008, I was walking down Broadway when I noticed something curious happening at Fiesta Mexicana, a restaurant located a few doors north of the Green Mill, inside the same building. The restaurant’s sign had been taken down for some maintenance work, exposing a part of the building’s façade that’s normally hidden.

The words “GREEN MILL GARDENS” were revealed. They’re etched in stone at this spot above the restaurant—a remnant of the era when the entertainment complex at this address was known by that name. Was Fiesta Mexicana where the entrance was located back in the 1920s?

A day after I’d seen the restaurant’s sign taken down, it was back in place. Once again, it obscured that historical clue. But a miniature sculpture of a windmill is visible on the façade above the restaurant, along with two faces. I think they’re masks representing comedy and tragedy—symbols that often appear on theater buildings—though it’s hard to tell which is frowning and which is smiling.

When Green Mill Gardens opened, the Chicago Daily Tribune ran an advertisement featuring a picture of the place. Seeing how large it was in 1914, I wondered how this palatial complex, which covered almost an entire acre of land …

… was transformed over time into the Green Mill venue and building that we know today:

In 2020, I returned to the topic of the Green Mill’s history when I answered a question for WBEZ’s Curious City. Uptown resident Karen Kinderman wanted to know why the neighborhood has so many old entertainment venues—places like the Green Mill, as well as the Riviera Theatre and the Aragon Ballroom.

You can hear my story and read the online version here: “From Cemetery Saloons to Movie Palaces: How Uptown Became an Entertainment Hub.”

As with many stories like this, I gathered far more information than I could include. And since then, I’ve found even more, combing through newspaper articles, court documents, property records, and old pictures. I talked about some of my findings during an event by Curious City and the Chicago Brewseum on April 12, 2023, at Carol’s Pub in Uptown. It was called “The Chicago Handshake: A People’s History of Beloved Bars.” Here’s a recap. Click “Listen” to hear the half-hour-long podcast recorded at the event.

This is the first in a series of blog posts about the history of Green Mill Gardens—with digressions on related topics, such as the early days of the place that became Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood; stories of some other local joints, including the Sunnyside Inn and Rainbo Gardens; the Prohibition Era; and, of course, musicians and mobsters.

This is something like a book, although at the moment, it’s a work in progress. I’m including some unanswered questions, along with notes about my research. I’m allowing myself to go down some tangents and rabbit holes that may or may not prove to be that relevant. And I’m sure this will be more detail than a lot of folks want.

I welcome corrections and comments, along with information about any stories, facts, or documents I may have overlooked. Feel free to email me at loerzel@comcast.net.

Continue reading with Chapter 1: Pop Morse’s Roadhouse and the Myth of 1907.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. Pop Morse’s Roadhouse and the Myth of 1907

Addendum: The “L” Arrives at Wilson

2. Piecing Together the Green Mill Puzzle (UPDATED)

3. Topography, Tombs, and Tolls

4. The Sunnyside, Cemetery Saloons, and the Rise of Ravenswood

5. The Early Years of Green Mill Founder Tom Chamales

6. The Battle Over Beach Rowdies, B-Girls, and Disorderly Women

7. Cabarets, Gardens, the Dance Craze, and That Paris Thing

9. Where Charlie Chaplin Slept, and Other Essanay Episodes

10. Miss Patricola, the Queen of the Cabaret

11. A Tribune Reporter Discovers Jazz and Blues

12. ‘What kind of noise is that!’ When Jazz Became Jazz

13. When the Blues Cured the Blues

14. Concerts and Controversies of 1915

15. ‘Personal Liberty’ Under Attack in 1916: The War on Cabarets

16. 1917: The Jazz Army Goes to War, and the Shows Go On

17. A Jazzy Trial in 1917 Chicago: Who Wrote Those Blues?

18. Chicago’s 1918 War Against Fun

19. Building Chicago’s Riviera Theatre

20. Chicago, June 30, 1919: John Barleycorn Must Die!

21. Prohibition’s Dawn and the Great Zion Beer Grab

23. The 1920 “Whisky Ring” and the Snitching Golfer

24. Ben Hecht and a Flapper Find “Nirvana” in Uptown

25. Cora Orthwein’s Trial: “I loved him and I killed him. It was all I could do.”

27. Cabaret Woes, “Evilly Disposed Persons,” and the Dancing Tenor’s Divorce

28. When Chicago Shimmied and Toddled

30. Green Mill Gardens’ Showdown With “Count” Yaselli

31. Capone-Adjacent Guys and Shady Land Deals

32. The Montmartre Years: Secret Gambling, Benny Goodman, and Girls Who “Salute”

33. The Uptown Theatre, a Palace of Dreams

34. Ted Newberry, Alleged Green Mill Mob Boss

35. The Aragon Ballroom, Dance Watchdogs, and Weird Echoes

36. Joe and Jack, Part 1: Showman and Hit Man

37. Joe and Jack, Part 2: “Guerrilla Warfare” and Green Mill Gigs

38. Joe and Jack, Part 3: The Attack

39. Joe and Jack, Part 4: “The Man the Gangsters Couldn’t Kill”

41. Uptown “Hell Holes” and the Red Hot Mamma

42. Texas Guinan’s Bang-Up Green Mill Show

Addendum: 1930 Photos of Lawrence Avenue in Uptown

PHOTO GALLERY

Below are some of the photos I’ve taken during various visits to the Green Mill since 2010.

FOOTNOTES

1 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 26, 1914, 4.

2 J.E. Lighter, ed., Random House Dictionary of American Slang, Volume 1, A–G (New York: Random House, 1994), 474.

3 Patrick Sisson, “An Oral History of the Green Mill,” Chicago Reader, March 20, 2014, https://chicagoreader.com/music/an-oral-history-of-the-green-mill/.

4 “Stella by Starlight” lyrics, accessed March 7, 2023, https://genius.com/Ella-fitzgerald-stella-by-starlight-lyrics.

5 Green Mill website, archived on January 4, 2007, https://web.archive.org/web/20070104002103/http://www.greenmilljazz.com/history.html.