Chapter 9 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

When Green Mill Gardens opened its doors in 1914, the surrounding neighborhood was a hub for the fledgling movie industry. “The astonishing reality is that Chicago filmmakers produced literally thousands of movies between 1896 and 1918, perhaps more than any other single city in the country during this time,” Michael Glover Smith and Adam Selzer wrote in their 2015 book Flickering Empire: How Chicago Invented the U.S. Film Industry.1

Motion pictures were still something of a novelty in 1908, when the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company opened its studio at 1333-45 West Argyle Street, where St. Augustine College is today. Moving pictures had been shown in Chicago for the first time in 1894, and moviemakers didn’t really start figuring out how to use these pictures to tell stories until the turn of the century.

“Movies”—a word that began appearing in Chicago newspapers around 1912—were rarely longer than 10 or 20 minutes. Theaters often showed them as part of vaudeville variety shows, interspersed between live entertainment. Movies were rarely advertised in Chicago newspapers, beyond the briefest of mentions, until around 1914. But this new form of entertainment was booming in popularity. A growing number of feature films—an hour or even longer—was coming out, boosting the prominence of movies as the main event for an evening or afternoon of entertainment. The names of actors had begun appearing on screen for the first time,2 and people were starting to get interested in the lives of these movie stars.

The Essanay studio was just five blocks northwest of Pop Morse’s roadhouse. So, it isn’t surprising that Essanay’s actors and film crew members visited the saloon, continuing into the era after 1914, when Green Mill Gardens replaced the roadhouse.

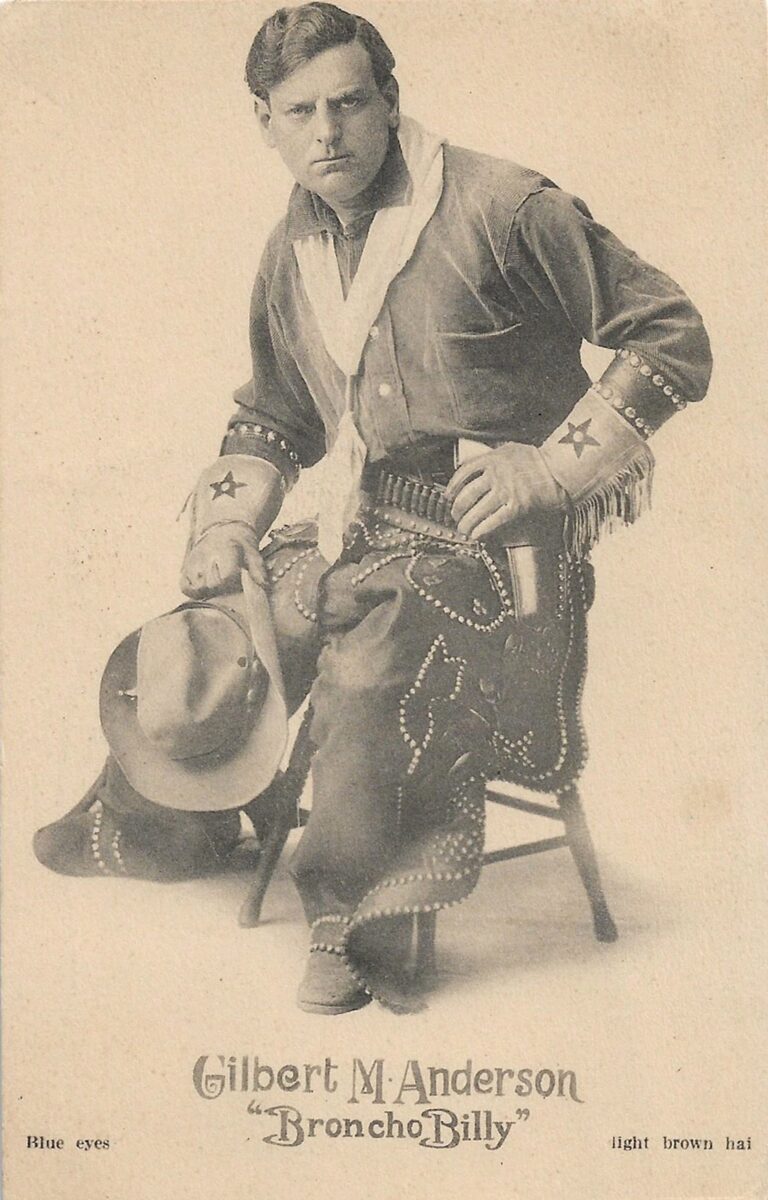

“They all used to come here,” Steve Brend, who owned the Green Mill Cocktail Lounge in later decades, told journalist Jacki Lyden for her 1980 book about Uptown. “ … There was even a hitching post outside for the horses the cowboy actors always rode, like Wallace Beery and Broncho Billy Anderson, who was half-owner of the studios.”3 In another interview, Brend told the Chicago Reader: “The Chamales brothers put a hitching post outside where the bus stop is. They did for Wallace Beery because he used to ride his horse over here.”4

As he often did with his stories, Brend may have jumbled a few of the facts, although there are some kernels of truth in these tales. It’s likely the roadhouse already had hitching posts before any movie actors playing cowboys showed up. The saloon was built in 1897, at a time when horses and horse-drawn vehicles were common modes of transportation. A map shows a hitching shed on the property just west of the main saloon building in 1905, three years before Essanay arrived in the neighborhood.

Gilbert M. Anderson. Wikimedia.

Essanay filmed portions of its cowboy movies nearby, trying to pass off Chicago scenery as western locations. These short films included The James Boys in Missouri (1908) and Broncho Billy’s Redemption (1910), starring Essanay’s co-owner, Gilbert M. Anderson, in his first appearance as his trademark character Broncho Billy.

It’s possible that Anderson and some of his costars hitched their horses on Lawrence Avenue when they stopped at the saloon for a drink after a day of filming. But Essanay didn’t use Chicago much for filming westerns after 1912, when it established a second studio in California, so it’s questionable how often actors rode horses to Green Mill Gardens after it opened in 1914.

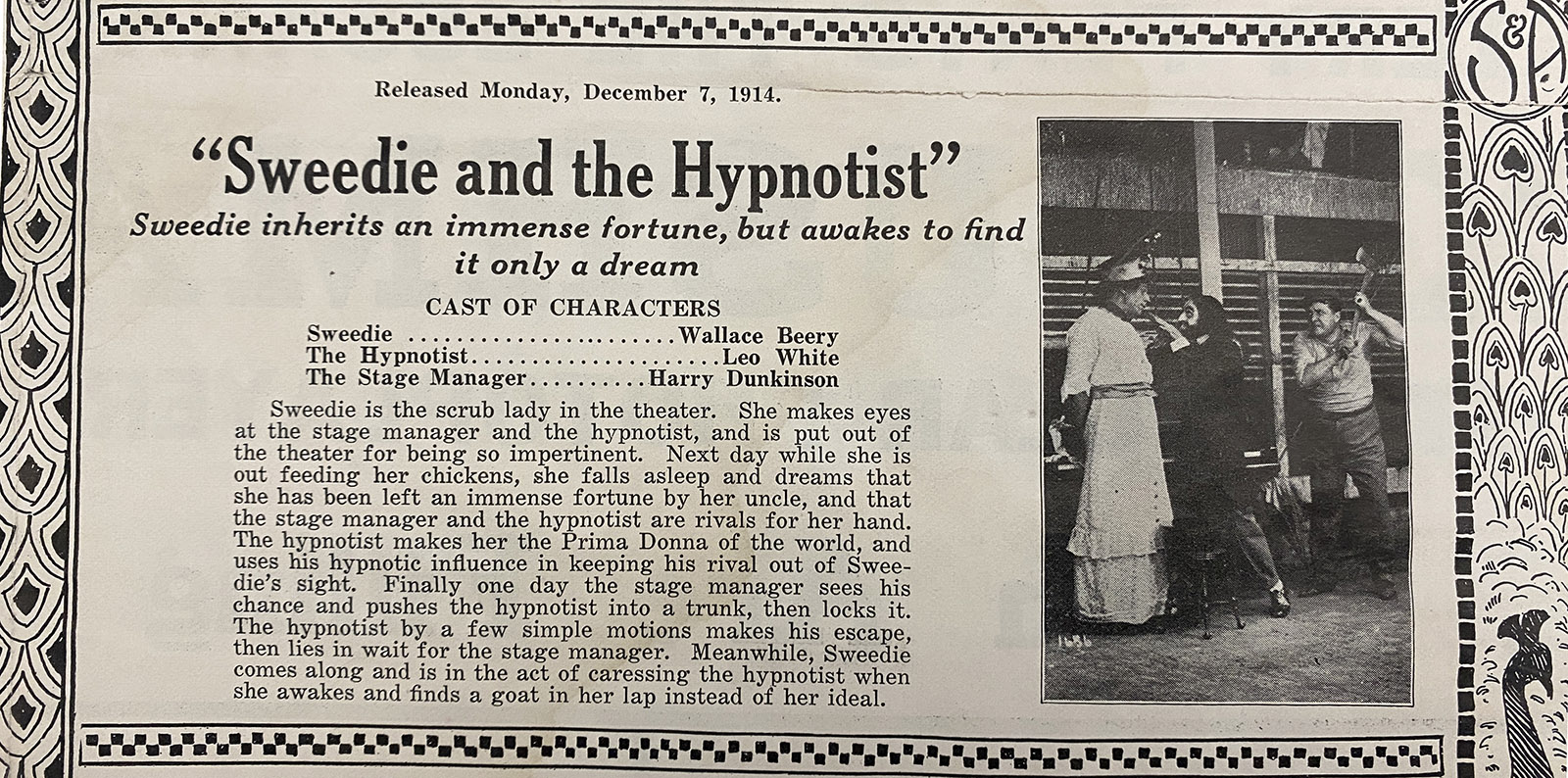

It also seems doubtful that a hitching post would have been installed specifically for Wallace Beery, who started acting for Essanay in 1913. At the time, Beery was best known for wearing women’s clothing in his recurring role as a Swedish maid named Sweedie,5 and he was often seen speeding around town in sporty automobiles, not trotting on horses.

Essanay News. Chicago History Museum.

Articles in Chicago newspapers and movie magazines confirm at some of the legend about Essanay’s movie stars visiting Green Mill Gardens. Those stories mention Green Mill visits by Ruth Stonehouse, an actress famed for her dancing, who also directed films; Ben Turpin, the perpetually cross-eyed comedian; and Beery, who was starting a long career that would include an Academy Award for Best Actor in 1931’s The Champ.6

It’s quite plausible that other Essanay players—like Anderson, matinee idol Francis X. Bushman, and the beautiful Beverly Bayne—spent some time at either Pop Morse’s roadhouse or Green Mill Gardens during the years when they were making movies just a few blocks away.

What about Gloria Swanson? She was only 15 years old when she visited the Essanay studios for the first time and got hired as an extra. She’d graduated from the eighth grade one week earlier, on June 26, 1914 (the same day as Green Mill Gardens’ grand opening). In spite of her youth, it’s conceivable that she may have visited Green Mill Gardens at some point before she departed from Essanay in 1915.7 This wasn’t long after some concerned people in the neighborhood had accused the Morse saloon of being a hangout for high school girls.8

Essanay’s most famous star was Charlie Chaplin—indeed, he’s arguably the most famous of all movie stars. He arrived in Chicago at the end of 1914, less than a year after making his movie debut for Keystone Studios, but already he’d made 36 short films, usually appearing on screen as a lovable, down-on-his-luck vagabond—the Tramp.9 He was already becoming of one cinema’s iconic figures. Chaplin is often mentioned as one of the actors who went to the Green Mill. That’s possible, but I haven’t yet found any solid evidence of an actual visit.

Charlie Chaplin, circa 1915. Wikimedia.

Chaplin worked at Essanay’s Chicago studios for just a short time, arriving on December 23, 1914, and departing less than a month later, after he’d made one two-reel comedy, His New Job.

Ben Turpin and Charlie Chaplin in His New Job.

That didn’t give him much time to hang out at Green Mill Gardens, although one reporter observed that Chaplin “seldom moved as fast while on screen as he did during the first few days of his stay in the Windy City.”10 Green Mill Gardens was a trendy and popular nightspot, having opened half a year earlier—just the sort of place you’d expect Chaplin’s new Chicago acquaintances to take him.

Chaplin had been to Chicago four years earlier, when he was touring with a vaudeville troupe. During that 1910 visit, “we lived uptown on Wabash Avenue in a small hotel,” Chaplin recalled in My Autobiography. (Although he called it “uptown,” he was clearly referring to Chicago’s Loop.) “Although grim and seedy, it had a romantic appeal, for most of the burlesque girls lived there. … The elevated trains swept by at night and flickered on my bedroom wall like an old-fashioned bioscope. Yet I loved that hotel, though nothing adventurous ever happened there.”

At that time, Chaplin wrote, “Chicago was attractive in its ugliness, grim and begrimed, a city that still had the spirit of frontier days, a thriving, heroic metropolis of ‘smoke and steel,’ as Carl Sandburg says. … It had a fierce pioneer gaiety that enlivened the senses, yet underlying it throbbed masculine loneliness.”11

Charlie Chaplin, photographed by White Studio, New York. Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library.

Tracking Chaplin’s whereabouts

When Chaplin returned to Chicago in late 1914, he stayed at the apartment where Gilbert Anderson (whose real name was Max Aronson) lived with his wife, Mollie, and their two-year-old daughter, Maxine.

“The day he came in, he walked around the apartment,” Mollie (or Molly) Anderson recalled in a 1968 interview with writer William F. Grisham. “We had a beautiful Christmas tree, shining with decorations, and my daughter was just a baby. Charlie looked at the tree, then at little Maxine. He walked around the tree with a radiant expression on his face. And he kept exclaiming: ‘A Christmas tree, a baby, a Christmas tree. It’s wonderful!’ He was so happy. He had never been in a home like ours. 12

Where was the Andersons’ apartment? In a 2007 article for Chicago magazine about Essanay, I wrote that it was at 1027 West Lawrence Avenue. My source for this address was David Kiehn’s 2003 deeply researched book Broncho Billy and the Essanay Film Company.13

If you look around the southeast corner of Lawrence and Kenmore Avenues, a few blocks east of the Green Mill, you won’t find that address. The building no longer stands; it’s now the site of a strip mall occupied by the Uptown Research Institute, a facility dedicated to the study and treatment of mental health disorders, and Dib, a sushi and Thai restaurant. This location is where the Andersons lived from 1911 through sometime in 1914, according to city directories, telephone books, and classified ads.

The southeast corner of Lawrence and Kenmore Avenues.

But as it turns out, that’s not where Charlie Chaplin slept. Further research shows that the Andersons moved in 1914. Their apartment was listed for rent in a Tribune classified ad on May 3.

And when the June 1914 white pages were published, there was no listing for Gilbert Anderson,14 who was spending most of his time making movies in California. “Although he had a charming wife and daughter in Chicago, he rarely saw them,” Chaplin recalled in his autobiography. “They lived their lives separately and apart.”15

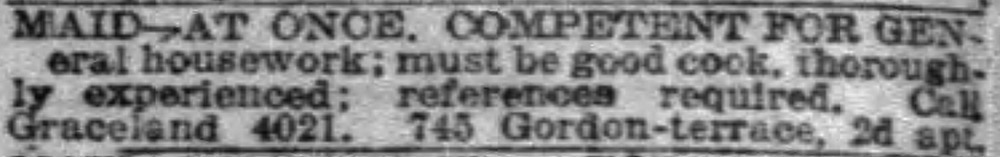

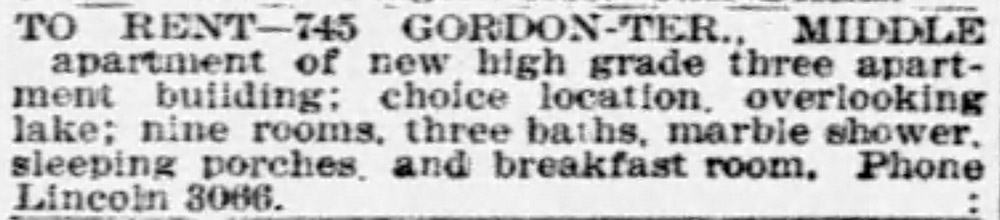

When a new edition of the white pages was published in October 1914, Anderson was listed with a residence at 745 Gordon Terrace, and the phone number Graceland 4021:

That phone number later appeared in a classified ad alongside the address “745 Gordon-terrace, 2d apt.”:

Anderson was listed at the same address in the February 1915 white pages:16

![]()

So, it seems clear that the Andersons were living at 745 West Gordon Terrace when Chaplin came to stay with them at the end of 1914. Chaplin later described Anderson as “the millionaire cowboy who had entertained me in Chicago at his wife’s sumptuous apartment.”17

The building’s “middle apartment,” apparently the same one where the Andersons lived, was listed for rent in a Tribune classified ad in August 1914, which described a “new high grade three apartment building; choice location, overlooking lake; nine rooms, three baths, marble showers, sleeping porches, and breakfast room.”18

Constructed in 1913,19 the building at 745 West Gordon Terrace seems to be the same one standing there today in the Buena Park neighborhood, a classic Chicago brick structure covered by ivy.

It’s a mile and a half from the old Essanay studios. The four-story building now has more than three apartments, so it seems likely that the large unit where the Anderson family lived was later broken up into smaller apartments.

The Andersons apparently lived in the building for just one year. The apartment was advertised for rent in September 1915, with availability on October 1.20 In 1916, the city directory showed actor Gilbert M. Anderson living at 429 West Melrose Street, in the East Lake View neighborhood:21

![]()

I emailed Kiehn, who’s the historian at the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum in California, to share my latest research on where the Andersons lived, and he replied: “G.M. Anderson was certainly a wanderer, as was his wife. I think he and his family moved about seven times when he was a kid living in St. Louis. When he was living in San Francisco in the 1920s and ‘30s he moved several times as well.”22

When Chaplin slept in the building on Gordon Terrace, he often slept late. “Very late,” Mollie Anderson recalled in her 1968 interview with Grisham. “And when he appeared, it was without a shirt collar. He had curly hair and never ran a comb thru it. The maids kept his food waiting. We heard no apology from him. So I simply did what I could. I was a young person, too, and I told him, ‘Charlie, run a comb thru your hair, and make yourself a little more presentable, and we’ll have breakfast.’”23

Did Chaplin stay at the Andersons’ apartment for the entirety of his month or so in Chicago? That isn’t certain. He could have lodged somewhere else for at least part of that time. According to Kiehn’s book, Chaplin stayed with the Andersons for two weeks. But Gilbert Anderson was out of town from January 2 until January 12.24 Would Chaplin have continued staying at the apartment alongside Mollie Anderson while her husband was absent?

If Chaplin did stay somewhere else, the details are unknown. There’s a persistent legend that he resided at the Brewster Building, at 2800 North Pine Grove Avenue.25

Brewster Building. Wikimedia.

According to a 1994 Tribune story, the Brewster’s elevator operator said that Chaplin had lived in the building—but he clearly got the time period wrong, saying this was “in the late 1920s.”26

An acquaintance of mine who lives in the Brewster told me he’d heard similar stories from the building’s former elevator operator, who also served as the doorman, but he’s skeptical that there’s any truth to these tales. “I think it’s unlikely Chaplin ever ‘lived’ here, though he may have stayed here, since the Lincoln Park Palace (Brewster’s original name) was a hotel,” he said.

Meanwhile, the owners of an apartment building at 1325 West Wilson Avenue have said Chaplin was “rumored to have lived” there,27 a claim repeated in a Block Club Chicago story.28 But this rumor is easily debunked by one basic fact: The building, originally known as the Norman Hotel, was constructed in 1928—long after Chaplin’s time in Chicago.29

It’s easy to imagine how rumors spread about where Chaplin stayed during his month in Chicago. Although he was still in the early days of his movie career, he was already famous—and Chicagoans seemed to be fascinated with his activities in their town.

Film Fun magazine’s 1915 illustration of Charlie Chaplin reading the magazine. Wikimedia.

George Spoor, who owned Essanay with Anderson, was skeptical about Chaplin’s burgeoning fame, but he quickly discovered that Chaplin was a genuine celebrity.

Spoor tried an experiment when he was lunching at one of Chicago’s big hotels.

“He gave a boy a quarter and had me paged throughout the hotel,” Chaplin wrote in My Autobiography. “As the boy went through the lobby shouting: ‘Call for Mr. Charlie Chaplin,’ people began to congregate until it was packed with stir and excitement.”30

Essanay hangouts

Whether or not Chaplin ever went to Green Mill Gardens, he did visit other places in the neighborhood. He ate with Essanay folks at Albert Stenberg’s bar, at the northwest corner of Broadway and Argyle Street, “where most of the actors and scenario writers took their lunch,” according to Charles J. McGuirk, an Essanay publicist and writer.

The former bar of Albert Stenberg, at 5000 North Broadway.

That building still stands at 5000 North Broadway. The corner space, which was a branch of Cathay Bank until 2021, is currently vacant. Top Tao Tea occupies another portion of the building.

Herb Graffis, who grew up in the neighborhood, recalled that Stenberg’s place offered free food at lunchtime, as many Chicago saloons did during the era, using food as a lure for drinkers.

“Stenberg was a generous Swede who keep free lunch until the evening, because down the street was the Essanay movie studio which engaged numerous talented parties who were not paid enough to get fat,” Graffis wrote in a 1973 article for the Chicago Sun-Times’ Midwest Magazine. “Among these geniuses I recall Charlie Chaplin, the funniest man I ever saw. He was tighter than a warped door, and when it came his turn to buy a drink at Stenberg’s, he side-stepped to ease bladder trouble.” 31

McGuirk said that these lunches at Stenberg’s were “the only time I ever saw Chaplin really excited.” According to McGuirk, the Essanay people did have to pay a bill for lunch. (Maybe this was the tab for drinks, or maybe not all of the food was free.) “It was the custom of a group of us to shake dice to see who would pay for all the lunches,” McGuirk wrote in a 1925 article for Photoplay. “And, if Chaplin ever thought of anything but his work, it was of that moment when he would test his luck against the rest of us.

“He watched every throw of the dice eagerly, bending over the table and insisting that the player leave them there while he rapidly counted up the points he had to beat. Given the box for his shake, he would make at least five false motions before he got the temerity to roll the dice.

“When he won, he would chuckle, his eyes snapping, and laughingly sympathize with the man who had been beaten. But if he lost, his expressive eyes would mourn for all the world to see. It wasn’t the money involved. I don’t think he ever thought of that. It was the fact that the fates, as expressed through the dice, had been unkind to him.”32

Graffis, a columnist for the Sun-Times, also recalled seeing the young Gloria Swanson in Stenberg’s joint. Keep in mind that Swanson began working at Essanay when she was 15 and she’d left by the time she was 16. Graffis would have been 21 or 22 at the time. Like any reminiscence written decades after the fact, Graffis’s story should be viewed with some skepticism.

“Another enthusiastic patron of Chez Stenberg was a pretty kid named Gloria Swanson,” he wrote. “She was a merry and pretty Swede kid who loved living and was going to keep on doing it. I always thought there was a girl who lost a photo-finish to Helen of Troy and Cleopatra as a girl who could make men line up in company front and count-off. Even at free lunch, she had the air of an empress. Years after my burning love for her had waxed and waned as a bright deep secret, and my wife could mention her name without making me faint, I thought of that Swanson kid as the female saint of Stenberg’s free lunch.”33

Another North Sider who grew up nearby, Roger McCabe, also remembered Essanay people frequenting Stenberg’s place.34 But McCabe had more vivid memories of the movie people hanging out at Winona Gardens, a Schlitz Brewery tied-house at 5120 North Broadway, which is now the South-East Asia Center.35

The South-East Asia Center, formerly Winona Gardens.

“My father was honored to be introduced to Frances X. Bushman one time at the Winona, an inn at Winona and Broadway,” McCabe recalled in a 1992 Edgewater Scrapbook article. “That was before Prohibition, and the Winona was famous for its ‘free lunch’ in those days. After buying a stein of beer or a drink or two, patrons could help themselves to a large cup of hot beef stew or a large corned beef sandwich. The inn had stained glass windows, a mahogany bar and wooden booths.”36

Someone identified only as “Herb” offered a similar reminiscence in a 1939 letter to the Tribune, recalling that the Winona Gardens and another bar known as “the Argyle” were the places “where the movie mimes from the Essanay studio used to relax—Gloria Swanson, the Beery boys, Francis X. Bushman, Beverly Bayne, and Charlie Chaplin.”37

If Chaplin ever did step foot inside Green Mill Gardens, one likely occasion would have been December 29, 1914, when Essanay performers took part in an evening of “minstrel and vaudeville entertainment” to raise money for Christmas charities. Green Mill Gardens donated its space for the event. The Chicago Daily News reported that participants would include Stonehouse, Beery, and Turpin, along with the venue’s star singer, Isabella Patricola. The story did not mention Chaplin.38

Motography later reported that Anderson and Chaplin “danced the ‘Broncho Billy’ waltz at a consolation party in the Windy City, appearing in their motion picture makeup. The dance was originated by Mr. Anderson and is one of the weirdest and funniest stunts on or off the stage.”39 But the magazine didn’t say exactly where this party took place. Kiehn’s book describes it as a charity event.40

On New Year’s Eve, the Andersons took out Chaplin to the College Inn, a popular restaurant in downtown’s Sherman House hotel (which stood at the northwest corner of Randolph and Clark Streets, where the Thompson Center is now). Inside the restaurant, one of the Howard brothers, a vaudeville act, spotted Chaplin. “He took Chaplin by the scruff of the neck and made him stand on a chair,” Mollie Anderson recalled. “Howard waved to the whole audience. When there was silence, he said, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, I want to introduce you to the funniest man in moving pictures—Charlie Chaplin!’”41

Green Mill connections

Around the same time, the Tribune mentioned another connection between Essanay and Green Mill Gardens: Kathleen Stevens, who wrote scenarios and acted for Essanay, had fallen in love with Harold Guentzer Margraff, a professional dancer at Green Mill Gardens. On January 5, 1915, the Tribune reported that Stevens—a 20-year-old from Decatur, Illinois—had attempted to kill herself when Margraff jilted her.

Most newspapers wouldn’t publish this sort of story today, but papers in that era often had less compunction about invading people’s privacy: The Tribune ran the news about Stevens’s attempted suicide on page 1. The story suggests that Essanay employees were socializing at Green Mill Gardens and, in some cases, finding romance there.42

(Margraff made news again three months later, when his mother applied for public aid, complaining that he wasn’t supporting her. Officials alleged that Margraff had given a $200 ring to his dancing partner, Mrs. Ralph Herz, a.k.a. Leah May, while spending $98 on dinner and $35 on flowers when he hosted her birthday party at Green Mill Gardens. Herz denied writing love letters to Margraff: “I didn’t write those ‘baby’ letters. I didn’t. And it’s positively false to say that Mr. Margraff gives me any of his salary.”43)

Motography published two reports in January 1915 about Ruth Stonehouse performing at Green Mill Gardens. In the magazine’s January 9 issue, a Chicago correspondent wrote: “Ruth Stonehouse, one of our Village’s fairest daughters, was the star attraction at Green Mill Gardens, one of the burg’s swell eating houses, one night this wk., when she danced for charity and the edification of all that could get into the place.”44

And on January 23, Motography reported that “Ruth Stonehouse’s ‘Storm’ dance at Green Mill Gardens, Chicago was greeted with storms of applause. What more appropriate—unless it might be a rain of flowers or the thunder of handclapping.”45

A portrait of Ruth Stonehouse by Benjamin Eggleston from Shadowland magazine, December 1922.

Chaplin shakes off Chicago’s dust

By the time this report was printed, Chaplin had abandoned Chicago and gone west in mid-January.46 On January 20, the Los Angeles Times reported that he was back in California, where he complained that Chicago was “too damn cold” to work in.47

Motography reported: “It was at first planned to have the comedian work in the Chicago studio, but on account of the lack of available exterior locations and the climatic conditions it was thought best to return to the West.”48

In spite of Chaplin’s quip about Chicago’s cold weather, the climate wasn’t his only reason for leaving. He’d also been unhappy with the working conditions at Essanay’s Chicago studio. Anderson later recalled: “He didn’t like the cameraman and he didn’t like the fellow who painted the scenery and he didn’t like this and he didn’t like that.”49 Or as Chaplin put it in his memoir: “Circumstances went from bad to worse.”50

The Chicago correspondent for Motography ruefully noted Chaplin’s departure in the magazine’s January 30 “Our Burg” column: “Chas. Chaplin, the comical chap what so recently arrived in our midst, has shook the dust of our fair city from his ft. and is even now back in that sunny Calif. at work.”51

Charlie Chaplin’s one and only Chicago-made movie, His New Job, was released in theaters on February 1, 1915.

Wallace Beery exits amid scandal

Chaplin wasn’t the only one who’d decided California was the place to make movies. Other Essanay stars also went west, including Beery—who departed under clouded circumstances in 1915.

As tempting as it is to look back on this era as a quaint time populated by charming characters, the silent movie industry also had a dark side. Gloria Swanson’s autobiography, Swanson on Swanson, revealed some stories about Essanay that would fit right in with Hollywood’s recent #MeToo controversies.

As tempting as it is to look back on this era as a quaint time populated by charming characters, the silent movie industry also had a dark side. Gloria Swanson’s autobiography, Swanson on Swanson, revealed some stories about Essanay that would fit right in with Hollywood’s recent #MeToo controversies.

When Swanson was 16, Beery started driving Swanson home in the evenings, after they’d finished filming for the day. (Swanson was living in 1915 with her mother and grandmother at 4215 North Leavitt Street, two miles southwest of the Essanay studio.52)

“I wasn’t interested in him that way in the least,” Swanson wrote. “He was probably old enough to be my father.” (He was 30 years old at the time.) “But I thought it would be fun to ride through the streets of Chicago in an open roadster, and it was, even though he turned out to be a terrible show-off.” On one of these drives, Beery took Swanson to his apartment. “Once we were inside I felt his hand on my hip,” she wrote. “I wasn’t startled in the least; I guess I had expected that too. I turned calmly and walked out the door. Outside I waited for him to open the car door for me, and then he drove me home.”

Swanson said she began avoiding him. In late May 1915, “Mr. Beery was soon involved in serious gossip,” she wrote. “Some girl’s parents had complained to Spoor about him. They had threatened to go to the authorities because their daughter was a minor, and the studio couldn’t afford such a scandal. Mr. Beery quietly disappeared, and we were told that he had gone out west to work at the other Essanay studio in California.”

The accusations against Beery are reminiscent of concerns that neighborhood residents had raised in 1913, when they’d claimed that teenage girls were frequenting the Morse saloon. Clearly, they were worried that older men would take advantage of these girls. Now, a movie star working in the neighborhood had done just that—at least, according to Swanson’s story, which was sketchy on the details. By the time Swanson’s book was published in 1980, Beery had been dead for three decades, so he wasn’t around to tell his side of the story.

“Within a week the payroll department demanded birth records on all the girls who worked at the studio, and men’s and women’s dressing rooms were strictly separated,” Swanson recalled. Apparently, now that Swanson was 16, Essanay considered her old enough to work at the studio.

In light of the situation with Beery, this may have had to do with the age of consent under Illinois law at that time. In 1915, the state considered it rape for any male 17 or older to “have carnal knowledge of any female person under the age of sixteen years and not his wife, either with or without her consent.” (Two decades earlier, the age of consent for girls in Illinois had been only 10 years old. The law was changed in 1886, when state legislators decided that girls couldn’t consent to having sex until they were 14. The law was revised again in 1905, raising the age to 16. Today, it’s 17.53)

It doesn’t appear that any stories about the Beery scandal made it into newspapers at the time, but word got out. The father of a young actress named Virginia Bowker, who’d shared a dressing room with Swanson, showed up at Essanay when the girl was in the middle of filming a scene. “Her father dragged her out of the studio, hollering that no daughter of his would work in that place anymore,” Swanson remembered.

And yet, Swanson followed Beery to California in January 1916, after receiving a postcard from him. She sought him out in spite of his scandalous past—and then she married him just after her 17th birthday. In her autobiography, she would accuse him of brutally raping her on their wedding night.

“I was now a member of the great conspiracy of silence,” Swanson wrote. “I had joined it in the moment I stifled my screams after Wally said to be quiet or I would wake up the whole hotel. I started paying in dues during the first weeks of my marriage by talking with my mother about anything except how unhappy I was. I recognized how many other members belonged as I sadly began to study the faces of women around me at work, in stores, on the street. And I realized to my dismay that no one could warn off … Gloria Swanson or any of the other starry-eyed girls who couldn’t wait to be initiated. The world of 1916 was a man’s world…”

Swanson and Beery divorced three years after they’d married.54

Gloria Swanson, in Pantomime magazine, 1921.

As Chaplin, Swanson, and Beery rose to greater stardom in Hollywood, the Chicago movie industry was fading. By 1916, “there was not much film work left in Chicago,” Smith and Selzer wrote in Flickering Empire. Essanay shut down in 1918, as did Chicago’s other major movie studio, Selig Polyscope.55

And with that, the curtains came down on the era when movie stars worked in the neighborhood around Green Mill Gardens.

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Footnotes

1 Michael Glover Smith and Adam Selzer, Flickering Empire: How Chicago Invented the U.S. Film Industry (London: Wallflower Press, 2015), 2.

2 Smith and Selzer, Flickering Empire, 28-29, 76, 89; “Feature Film,” Wikipedia, accessed June 28, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feature_film; Brian Cronin, “Who Was the First Actor Credited in a Movie’s Opening Credits?,” Pop Culture References, accessed June 25, 2023, https://popculturereferences.com/who-was-the-first-actor-credited-in-a-movies-opening-credits/; Ken Kahre, “Who was the first movie actor or actress to receive screen credit?,” accessed June 25, 2023, https://www.quora.com/Who-was-the-first-movie-actor-or-actress-to-receive-screen-credit.

3 Jacki Lyden, Landmarks and Legends of Uptown (Chicago: Jacki Lyden, 1980), 29.

4 Robert Ebisch, “Whatever Happened to the Green Mill,” Chicago Reader, Oct. 29, 1982, 1-2, 20, 22, 24.

5 Smith and Selzer, Flickering Empire, 90, 93, 99, 102.

6 “Hotel Guests Help Charity,” Chicago Daily News, December 26, 1914, 7.

7 Stephen Michael Shearer, Gloria Swanson: The Ultimate Star (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2013), 12-15, 21.

8 “Demand ‘Lid’ for North Shore Cafe,” Chicago Examiner, January 17, 1913, 4.

9 “Charlie Chaplin Filmography,” Wikipedia, accessed June 25, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlie_Chaplin_filmography.

10 Charles J. Caine, “Charles Chaplin in a Serious Mood,” Motography, January 16, 1915, 95. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433034835631?urlappend=%3Bseq=117%3Bownerid=13510798903613635-121

11 Charles Chaplin, My Autobiography (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1964), 126-127.

12 William F. Grisham, “Those Marvelous Men and Their Movie Machines,” Chicago Tribune Magazine, December 7, 1969, 42-49.

13 David Kiehn, Broncho Billy and the Essanay Film Company (Berkeley, CA: Farwell Books, 2003), 185.

14 Chicago city directories, 1911-14, Fold3.com; Chicago white pages, February and June 1914, Chicago History Museum; classified advertisements, Chicago Daily Tribune, October 9, 1913, 17; January 18, 1914, 63; April 9, 1914, 24; May 3, 1914, 83.

15 Chaplin, My Autobiography, 169.

16 Chicago white pages, October 1914 and February 1915, Chicago History Museum; 1915 Chicago city directory, Fold3.com; classified advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, September 5, 1915, 53.

17 Chaplin, My Autobiography, 169.

18 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, August 16, 1914, 57.

19 May 1913 building permit and index card for 745 Gordon Terrace, Chicago Building Permit Street Index Reel UID CBPC_IND_038, 1039; Chicago Building Permit Ledgers Reel UID CBPC_LB_14, 52, Chicago Building Permits Digital Collection 1872-1954, University of Illinois at Chicago Library.

20 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, September 5, 1915, 58.

21 1916 Chicago city directory, 113, Fold3.com.

22 David Kiehn, email to author, June 2, 2023.

23 Grisham, “Those Marvelous Men.”

24 Kiehn, Broncho Billy, 185-187.

25 “Brewster Apartments,” Wikipedia, accessed June 3, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brewster_Apartments.

26 Mary Maguire, “Past Is Present,” Chicago Tribune, February 4, 1994, section 8, 20.

27 “No. 1325 Wilson,” Flats Chicago, archived December 19, 2013, https://web.archive.org/web/20131219045733/http://www.flatschicago.com/uptown-chicago-apartments/1325-wilson/1325-2-bedroom-apartments/chaplin.

28 Joe Ward, “Northalsted-Based Elevate Coffee Opening Uptown Location In Former Home Of Heritage Outpost,” May 5, 2023, https://blockclubchicago.org/2023/05/05/northalsted-based-elevate-coffee-opening-uptown-location-in-former-home-of-heritage-outpost/.

29 Index card for 1928 building permit at 1317-27 West Wilson Avenue, Chicago Building Permit Street Index Reel UID CBPC_IND_118, 1337, Chicago Building Permits Digital Collection 1872-1954, University of Illinois at Chicago Library; Martin C. Tangora, “Sheridan Park Historic District,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form, July 25, 1985, 17, accessed June 1, 2023, https://www.james46.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Sheridan-Park-National-Register-District-Chicago-text.pdf.

30 Chaplin, My Autobiography, 167.

31 Herb Graffis, “A Young Man’s Fancy When Chicago Was in Bloom,” Chicago Sun-Times, Midwest Magazine, November 18, 1973, 48.

32 Charles J. McGuirk, “I Knew Them When,” Photoplay, March 1925, 113, https://archive.org/details/pho28chic/page/n377/mode/1up.

33 Graffis, “A Young Man’s Fancy.”

34 Roger McCabe, “A Son Looks Back,” Edgewater Scrapbook 4, no. 2 (spring-summer 1992), http://www.edgewaterhistory.org/ehs/articles/v04-2-6.

35 “Final Landmark Recommendation: (Former) Schlitz Brewery-Tied House,” adopted by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, February 3, 2011, https://www.chicago.gov/dam/city/depts/zlup/Historic_Preservation/Publications/5120_N_Broadway_Tied_House_Report.pdf.

36 McCabe, “A Son Looks Back.”

37 “A Line O’ Type or Two,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 15, 1939, 20.

38 “Hotel Guests Help Charity,” Chicago Daily News, December 26, 1914, 7.

39 “Brevities of the Business,” Motography, 13, no. 4 (January 23, 1915), 138, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433034835631?urlappend=%3Bseq=164%3Bownerid=13510798903613635-170.

40 Kiehn, Broncho Billy, 185-187.

41 Grisham, “Those Marvelous Men.”

42 “Actress Tries Suicide; Says Dancer Jilted Her,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 5, 1915, 1.

43 “Mrs. Herz Denies Letters,” Chicago Daily News, March 4, 1915, 5.

44 “Our Burg,” Motography 13, no. 2 (Jan. 9, 1915), 60. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433034835631?urlappend=%3Bseq=78%3Bownerid=13510798903613635-82.

45 “Just a Moment Please,” Motography 13, no. 4 (January 23, 1915), 128. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433034835631?urlappend=%3Bseq=154%3Bownerid=13510798903613635-160.

46 Kiehn, Broncho Billy, 189.

47 “Charley Chaplin,” Los Angeles Times, January 20, 1915, III 4.

48 “Chaplin Returns to California,” Motography, 13, no. 5 (January 30, 1915), 166, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433034835631&view=1up&seq=196.

49 Kiehn, Broncho Billy, 189.

50 Chaplin, My Autobiography, 166.

51 “Our Burg,” Motography 13, no. 5 (January 30, 1915), 168, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433034835631?urlappend=%3Bseq=198%3Bownerid=13510798903613635-210.

52 1915 Chicago city directory listings for Gloria Swanson, 1603, and Mrs. Adelaide M. Swanson, 1601, Fold3.com; her grandmother, Bertha Lew, is at the same address in the 1920 U.S. census, Illinois, Cook, Chicago Ward 26, enumeration district 1548, sheet 9B, Ancestry.com.

53 “Age of Consent Laws (Table),” Children & Youth in History, accessed July 3, 2023, https://chnm.gmu.edu/cyh/primary-sources/24.html; Harvey B. Hurd, The Revised Statutes of the State of Illinois, 1915-1916 (Chicago: Chicago legal news company, 1916), 921; 1880: 393; 1903: 600.

54 Gloria Swanson, Swanson on Swanson (New York: Random House, 1980), 37-38, 60-63; Shearer, Gloria Swanson, 21-22.

55 Smith and Selzer, Flickering Empire, 147, 155.