Chapter 8 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

If you stand near Lawrence and Magnolia Avenues, looking toward the northeast corner, you’ll see the giant Uptown Theatre, which was built in 1925. Try to imagine what this corner looked like from 1914 until 1923.

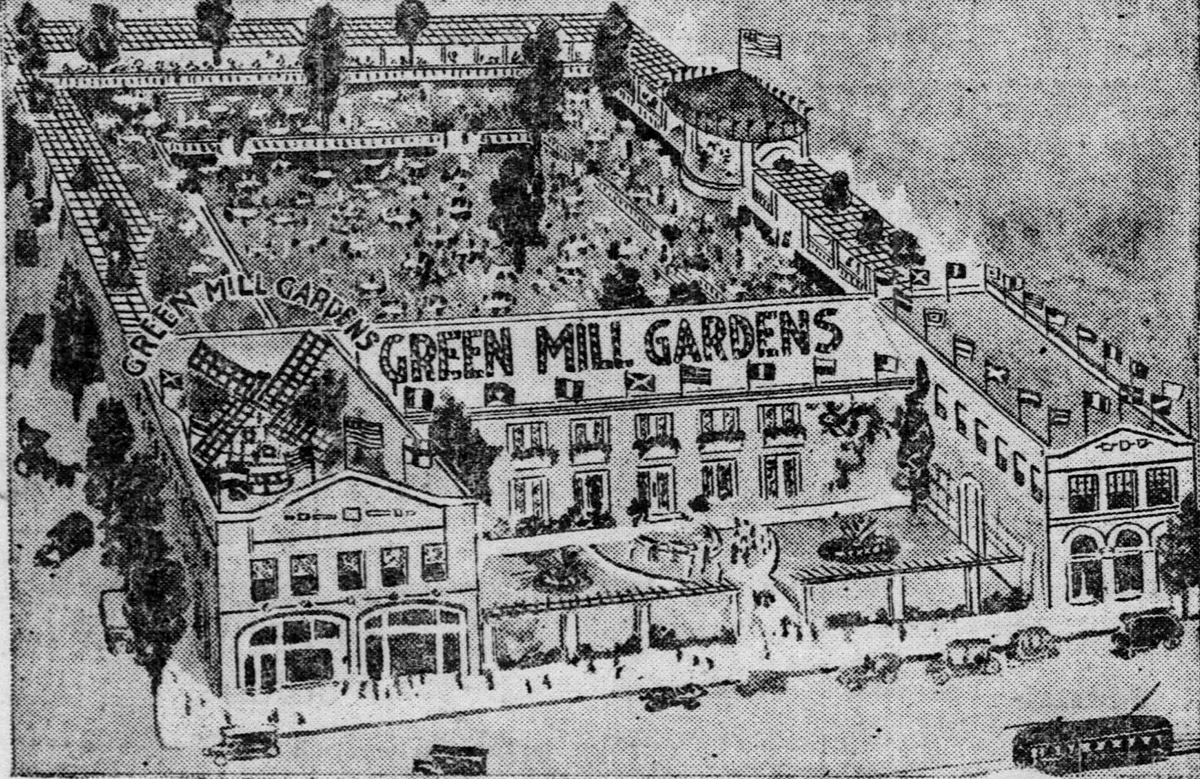

Before the theater was constructed, this land was a garden filled with tables, where people sat drinking beer and cocktails, alongside a dance floor and an outdoor stage where bands played. You wouldn’t have been able to see much of that from across the street, though—it was all surrounded by walls. This was the outdoor portion of the Green Mill Gardens complex.

“The Green Mill sunken garden has probably the best dance floor in the city of Chicago,” Reform Advocate magazine commented in 1916. “The scene presented any night, when the beautifully gowned women and the well-attired men dance to the strains of an orchestra of post-graduate musicians, while the tables, topped with linen and relieved with the multi-colored attire of the guests, form a picturesque background, is worth alone the visit.”1

This palace of entertainment opened in June 1914 at the same spot where Charles “Pop” Morse had built his humble roadhouse 17 years earlier.

A Lease on Life

As Tom Chamales prepared to construct Green Mill Gardens, he signed a new lease in 1913 with the woman who owned the roadhouse and the land under it—Morse’s daughter, Catherine Hoffman. Chamales secured the location for the next quarter century, with a lease running through April 30, 1938. His monthly rent would be $750 (roughly $23,000 in today’s money), gradually increasing to $1,000 by 1925. Chamales also agreed to pay property taxes on the building and improvements.

Meanwhile, Hoffman agreed to lend Chamales $35,000 to help with construction costs, which were estimated at $45,000. Although Chamales was constructing the building, he wouldn’t own it. When the lease ended in 1938—or if it was terminated earlier—he would be required to “yield up said premises to the Lessor [Hoffman] in good condition and repair, loss by fire, and ordinary wear excepted, and will deliver the keys at the office of Charles Hoffman,” who was Catherine’s husband. When the lease ended, Catherine Hoffman would owe Chamales some money for the buildings he’d constructed—but the formula set $17,500 as the maximum payment.

This deal put Chamales in a curious position: He was investing money to construct an entertainment complex, knowing that he’d wouldn’t actually own the property—and that he might be forced to hand over the keys in 1938, if not sooner. Did 1938 just seem like it was far off in the future, nothing to worry about for the time being? Or perhaps Chamales thought he’d make enough money at Green Mill Gardens to make it all worthwhile. Or maybe he was already thinking about ways that he might be able to emerge eventually as the property owner.

The agreement between Chamales and Hoffman anticipated that problems might arise from selling alcohol, which had been a flashpoint for controversies throughout Chicago’s history. Chamales agreed to use the property “for no other purposes except that of conducting a saloon, restaurant, cafe, concert hall, or other legitimate business.” And Hoffman said she wouldn’t be held responsible if Chamales used the site for “the unlawful sale … of any intoxicating liquors.” Chamales agreed not to sublease the property to any other “saloon, cafe, or concert hall purposes” without Hoffman’s written permission.2

Chamales also signed a lease with real estate agent Edward E. Hamer3 for the property just west of the roadhouse, which he would use for the new venue’s outdoor gardens. That lease also ran through 1938.4 But after Chamales signed these leases in February 1913, Charles and Catherine Hoffman bought the western property in a series of three transactions over the following 10 months.5 Was Chamales aware of their plans? Or did they pull off these deals on the sly? In any case, the Hoffmans succeeded in securing more of the land that Chamales was using as the site for his new venue. They now owned all of the property where Chamales planned to open Green Mill Gardens.

Two weeks after signing the new lease with Catherine Hoffman, Chamales advertised in Construction News, seeking bids for subcontractors to work on the project. He’d already hired O.W. Rosenthal & Co. as the general contractor. The ad said it was a $75,000 project: a two-story brick building with a café, kitchen, buffet, billiard hall, and summer garden. It said the building would be 51 by 158 feet, which did not turn out to be accurate, and it did not mention any architect.6

Curiously, the lease required Chamales to construct “a building in accordance with plans and specifications prepared by O.W. Rosenthal & Company, architects.”7 The company was run by Oscar W. Rosenthal—a prominent contractor who would serve as president of the Chicago Building Congress8 and lead a committee that rewrote the city’s building code9—and Joseph B. Cornell. They weren’t described as architects in the city directory.10

A Bartender Named Butterly

To pull off his plans, Chamales needed John F. Butterly to move his own saloon out of the way. Butterly had a bar in a leased building at 1216–1218 West Lawrence Avenue, just west of the Morse roadhouse.11

Butterly, an Irish immigrant, apparently had a long history at this street corner. According to a letter published in the Chicago Daily Tribune in 1924, Butterly “helped make famous ‘Pop’ Morse’s place in the Wilson avenue prairie days”—although it’s not clear precisely what he did to make the place famous. The gist of this letter (which was signed with the initials “J.D.”) seems to be that Butterly was a well-known character at several Chicago saloons over the years.

Butterly had previously been a prominent member of the “crew” that drank at Malachi Hogan’s saloon12 at 42 North State Street (which became 176 North State after 1911),13 when it inspired “When Hogan Paid His Rent,” a hit song from 1891 by J.W. Kelly, a garrulous Irish storyteller known as “The Rolling Mill Man.”14

In the song, a rent collector shows up at Hogan’s bar and demands payment. “Treat the boys, says Hogan, or I’ll never pay a cent,” the song goes. A wild brawl ensues, teaching the rent collector a lesson: Always buy drinks for the boys at Hogan’s saloon. The chorus goes:

Each gave back the other what he sent,

The bones they didn’t break were badly bent,

They slugged each other, hugged each other, and with sticks they clubbed each other,

Any kind of fighting went when Hogan paid his rent.15

(Here is a recording of the song from around 1961 by “Square” Jim MacDonald.)

Butterly was around 17 or 19 years old when the song came out in 1891.16 According to that 1924 letter in the Tribune, Butterly was “Malachy Hogan’s man,” suggesting a close connection between the men. “After the song went its way from John Long’s theater in State street, the Butterly crew drifted to Hogan’s and Batchelder’s places in State street and from there wound up at Owen Murray’s, across from the Palmer house,” J.D. wrote.17

Butterly was working as a bartender by 1898. Sometime after 1900, he moved to the North Side.18 And in 1910, he was working as a salesman at a hardware store. By 1911, he had his own saloon on Lawrence Avenue and was living with his wife and daughter a couple of blocks away, at 4645 North Magnolia Avenue.19 On January 27, 1914, Chamales paid Butterly $4,500 to take over his lease, while agreeing to let Butterly rent space for a saloon in the new Green Mill Gardens building’s north wing, facing Broadway.20

The Walls Go Up

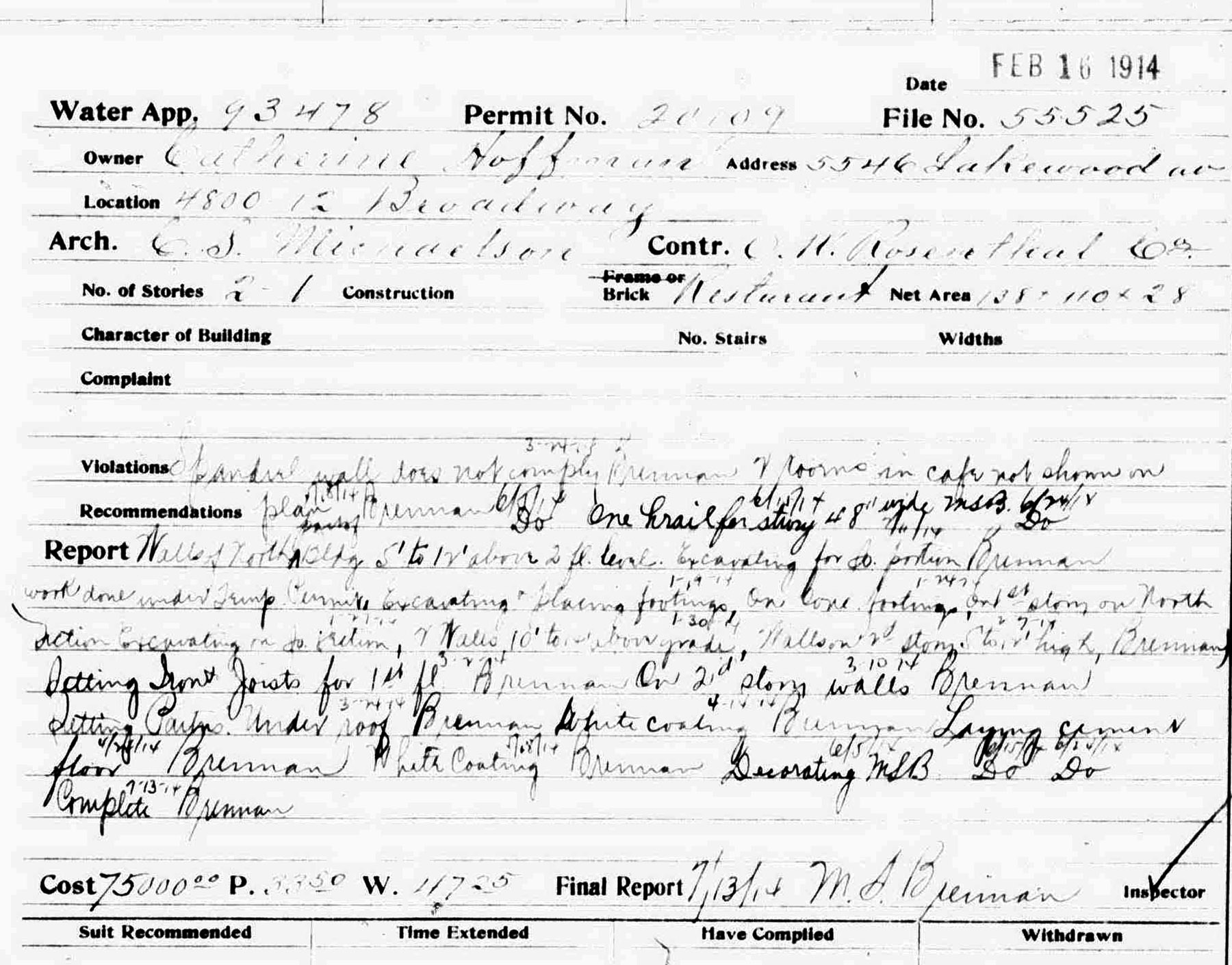

The building’s walls were already rising up in mid-January 1914, even though the city had issued only temporary building permits. The project finally received a permit on February 16, 1914, with Catherine Hoffman listed as the property’s owner. The plan was to construct a two-story brick restaurant stretching 110 feet along Lawrence Avenue and 138 feet along Broadway.

By now, the project had a new architect: Christian S. Michaelsen,21 who later formed a partnership with Sigurd A. Rognstad. Michaelson and Rognstad would design some iconic Chicago buildings, including several that were completed in 1928: the Garfield Park Fieldhouse, the Northside Auditorium Building (now the Metro concert venue), the On Leong Merchants Association Building (now Pui Tak Center), and the former Won Kow restaurant.22

Green Mill Gardens’ second-story walls were up by March 10, 1914,23 a week before the Chicago City Council voted to add cement sidewalks on both sides of Lawrence Avenue from Broadway to Clark Street.24 On April 24, workers were laying the building’s cement floor.25

On June 10, 1914, Tom Chamales received a building permit to construct a “Brick Enclosure for Summer Garden,” with a six-foot-high wall encompassing a 138-by-140-foot space west of the building, with Michaelson listed again as the architect.

On June 15—just five days later—building inspector M.S. Brennan reported that the wall had been constructed to its full height, and the bandstand’s metal lathing was in place.26

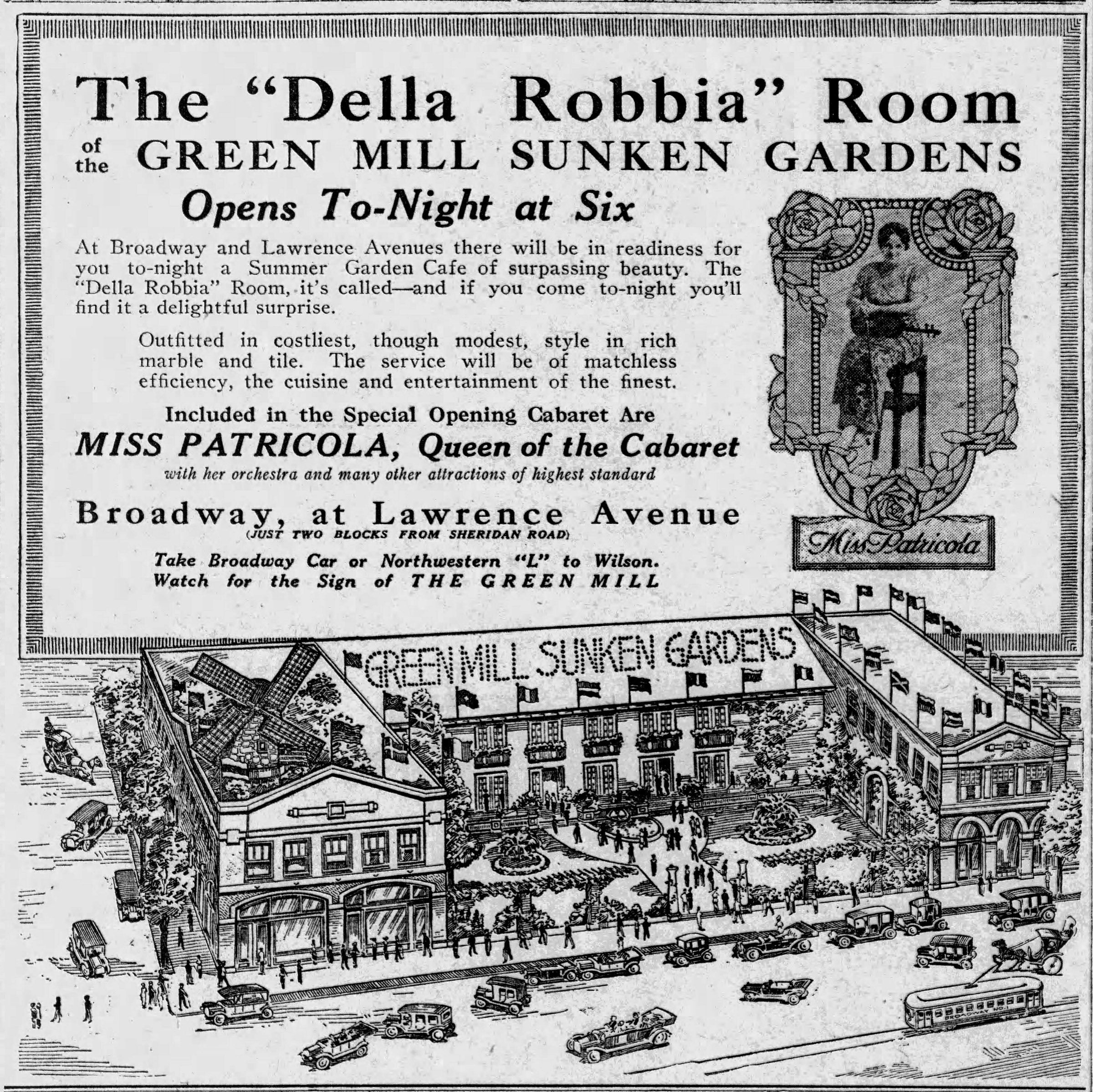

By the time Brennan made that report, it was already two days after the venue had announced its opening in the Chicago Examiner, calling itself “the Green Mill Sunken Gardens.” The word “sunken” would sometimes appear in advertisements, and sometimes not; it apparently wasn’t part of the official business name.

Opening Night(s)

The venue’s earliest ads touted an indoor space called the Della Robbia Room, “a Summer Garden Café of surpassing beauty … outfitted in costliest, though modest, style in rich marble and tile.” This wasn’t the first place with that name—there was already a well-known dining space known as the Della Robbia Room in New York’s Vanderbilt Hotel. It was named after Luca della Robbia, a Renaissance sculptor from Florence known for his colorful, glazed terra cotta statuary.27

According to the Examiner ad, Chicago’s own Della Robbia Room was opening at 6 p.m. on June 13. The ad promised: “The service will be matchless efficiency, the cuisine and entertainment of the finest.” The entertainment at this “Special Opening Cabaret” would include Isabella Patricola, “Queen of the Cabaret with her orchestra and many other attractions of highest standard.”

Realizing that some Chicagoans might have trouble finding this new nightspot—in a part of the city that had been almost rural a decade earlier—Green Mill Gardens included advice about how to get there. The ad said it was “just two blocks from Sheridan Road.” (Actually, it was four blocks away.) And it noted: “Take Broadway Car or Northwestern ‘L’ to Wilson. Watch for the sign of THE GREEN MILL.”28

But even as that advertisement appeared, work was continuing on the building. Brennan, the city inspector, noted some violations: The café included two rooms that weren’t shown on the blueprints. And he found problems with a spandrel wall and a “hrail,” likely an abbreviation for “handrail.” It’s unknown how these problems were resolved. Brennan did not give his final approval on the building until July 13, weeks after the venue opened for business.29

Another ad appeared on June 26—this time in the Chicago Daily Tribune—announcing that Green Mill Gardens was opening at 6 p.m. that night. If the Dellia Robbia Room had opened for business on June 13, then this June 26 ad may have been announcing the outdoor garden’s opening. Or perhaps this was the venue’s grand opening, following an earlier “soft opening.”

“Come Tonight to the coolest spot in Chicago—the only real Sunken Gardens in America—the most novel summer garden where every night is a gala night,” the ad proclaimed. Was it truly the only sunken gardens in America? That seems doubtful, but it depends on precisely what that meant. The use of the term “sunken” suggests that the venue’s garden space was below street level. “Come where you can spend your evening in comfort and pleasure in a delightful spot encircled by a terrace of flowers and climbing vines,” the ad continued.30

The Green Mill Gardens building faced Broadway, with two wings jutting east toward the street and a courtyard in the middle.

At the corner of Broadway and Lawrence, a windmill was on the roof. “There used to be a big windmill on top of the building,” the Green Mill Cocktail Lounge’s later owner, Steve Brend, told the Chicago Reader in 1982. “The arms would turn and were covered with lights.”

How long did the windmill last, and what eventually happened to it? That is one of the building’s unsolved historical mysteries. The windmill was gone by the time photos were taken in the mid-1920s.

Clues Point to the Past

West of the building, a walled-in garden stretched all the way to the next street, Magnolia Avenue, covering land where the Uptown Theatre was later built. “Outside the place had high walls around it so you couldn’t see in,” Brend said, repeating the stories he’d heard about that era. “There were walks through the gardens and tables, around a raised outdoor dance floor. It was really somethin’.”31

Today, you can see a narrow corridor on the north side of Lawrence Avenue, half a block west of Broadway, where garbage dumpsters are stored between the Uptown Theatre and the Green Mill building.

It’s hard to see from the sidewalk, but the Green Mill building’s west wall shows some traces of what it originally looked like in 1914.

“The remnants of a series of French doors, which faced the outdoor beer garden, can be seen, although bricked up to facilitate the installation of windows,” David Syfczak, who has been the Uptown Theatre’s caretaker since 1996, told me. “Their concrete sills at the interior floor level remain in the exterior masonry wall.”

The exact layout of Green Mill Gardens in that era isn’t certain, but it appears that the indoor space for entertainment was in the building’s northwest portion. “A rooftop view shows the truss roof, which eliminates the need for support columns, indicative of vast floor space below it which would be required for dancing and entertainment purposes,” Syfczak said. That curved roof is visible in this 2023 aerial photo, from Cook County’s NearMap website.

Note that the right side of photo shows a smaller second section of humped roof—the portion of the building that was added in 1922, covering up the original courtyard. Tim Samuelson, the city of Chicago’s cultural historian emeritus, told me that this “indicates that there were two areas of clear-span trusses to create column-free spaces” during that era.

“There is a large corridor/hallway to the rear of all of the storefronts that runs the length of the building north to south,” Syfczak said. “In the northwest and southwest corners of that rear corridor are wide staircases leading to the second-floor former ballroom.” Before the building was reconfigured to create that ballroom space on the second floor—sometime in the late 1920s or early 1930s—it had balconies overlooking the main floor of the performance space. Here’s a glimpse of a staircase in the building’s southwest corner.

The building’s south wing—the portion where the Green Mill Cocktail Lounge is now, along with Carmela’s Taqueria and Birrieria Zaragoza, which recently took over the former Broadway Grill space—was part of the original Green Mill Gardens complex that opened in 1914.

The Chicago city directory listed two addresses in 1917 for Tom Chamales’s saloon, 1210 West Lawrence Avenue and 4802 North Broadway, indicating there were entrances on both streets.32

Note how the north end of Carmela’s Taqueria is two steps higher than the rest of this small restaurant. Is that a remnant of steps leading into the entertainment space that was north of this spot?

Glowing Reviews

Green Mill Gardens’ advertisements in 1914 emphasized that the venue’s indoor restaurant was lavish, but not garish. “Dine in our Della Robbia Room designed with rare skill and carried out in the costliest, though not gaudy, marbles and tile,” said Tribune ad. “Attractive and rich—a place where you will enjoy the finest cuisine prepared by expert chefs. The cleverest entertainers.”

Once again, the headline act was “The Queen of the Cabaret, Miss Patricola.” The ad noted: “With her orchestra of 25 pieces and many other stellar attractions, especially engaged for tonight’s opening, will entertain you as you have never been entertained before.”33

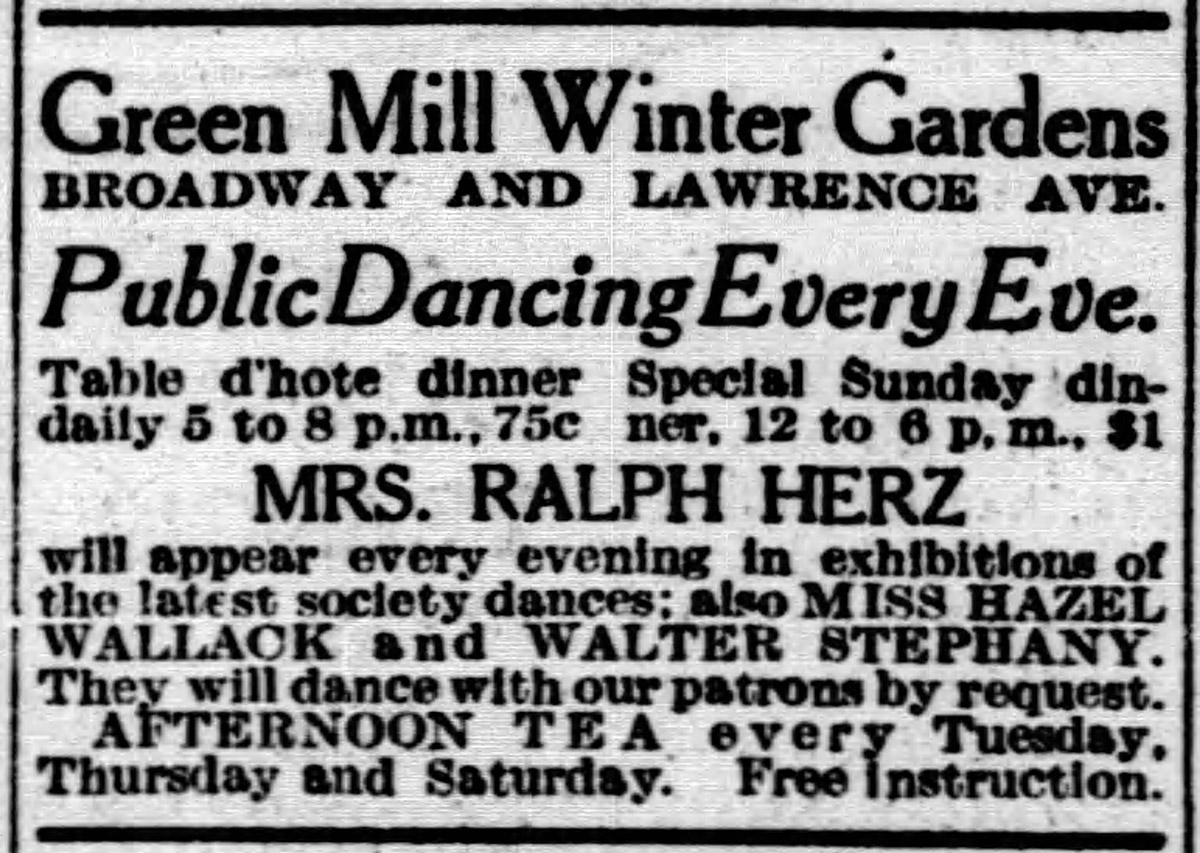

At the end of summers, the entertainment at Green Mill Gardens shifted indoors. The Della Robbia Room began holding “public dancing” every night starting on October 12, 1914, with “Mrs. Ralph Herz” (a.k.a. Leah May34) presenting “exhibitions of the latest society dancers.” Professional dancers would dance with patrons by request.

The venue also hosted “tango teas” on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons. A special Sunday dinner, served between noon and 6 p.m., cost $1. And a table d’hote dinner (typically, a meal that gave customers little, if any, choice about their order) was served from 5 to 8 p.m. each evening, for 75 cents.35

During 1914—that year when Green Mill Gardens was constructed and began welcoming guests—Chamales had a residence at 5719 South Prairie Avenue, 13 miles away on the South Side.36 But by 1915, he’d moved closer to Green Mill Gardens, living just around the corner, at 4749 North Magnolia Avenue. In 1916 and 1917, he lived at 4755 North Magnolia.

His brother William also lived nearby, at 4700 North Broadway, in 1915. But William moved down to the Loop in 1916, as he ran the Savoy restaurant on South Wabash. In 1917, he returned to the North Side, working as the manager of Green Mill Gardens while residing at the Plymouth Hotel, on the north side of Leland Avenue between Racine Avenue and Broadway.37

When Green Mill Gardens’ outdoor area reopened around the end of May 1915, it included “a new outdoor dance pavilion, accommodating three hundred couples,” the New York Clipper reported. The newspaper commented: “The beautiful electric sign in front of the gardens has long been the subject of enthusiastic comment.”38

That July, the Chicago Daily News reported: “The Green Mill garden … continues to be the mecca of those who enjoy music, while the dance ‘mad’ crowd takes to the new outdoor dancing floor.”39 An ad described “Patricola and Her Forty Entertainers”—apparently, an even bigger band—performing at the “Finest Open Air Floor in America, with the Best Dancing Music in Town.”40

In the summer of 1916, Green Mill Gardens received a glowing review in the Reform Advocate. The rabbi and scholar Emil G. Hirsch published this weekly magazine in Chicago “in the interest of Reform Judaism,” but it also included commentary on other topics for its national audience of Jewish readers. The magazine argued that Green Mill Gardens was classier than other amusement gardens:

The day of tinsel and glare had its day. It is dying. Good taste killed it. In no field of endeavor was it more abused than in amusement gardens.

The idea of a cabaret, or recreation garden, was at one time confined simply to making so much noise that the diners could not find an opportunity of thinking. The properties of the places were designed with no regard for permanence or dignity, but with a dazzle and ornateness which struck the eye of the visitor hard. Gentlemen and ladies declined to visit gardens for this reason.

Tom Chamales, whose whole life has been spent in the business, saw the handwriting on the wall. He interpreted the desire and inclination of gentlemen and ladies. He built the Green Mill Gardens. …

He built a wonderful, classic Della Robbia room, and every inch of space was planned with care to present a finished product of dignity and beauty. He built a splendid sunken garden adjoining. It is a delight to the eye and a comfort to the soul. The atmosphere spells relaxation. People do not come to the Green Mill Gardens for excitement. They come for rest. They come to eat, drink, laugh and dance. The food is as good as can be purchased. …

Chamales’ waiters are artists. They are the sons of the grandsons of waiters. They are there to serve, and they know how. There is no silly obsequiousness, no superciliousness, attempt to intrude or dominate. If you want a waiter, he is there. If you don’t—he is there anyway, but you cannot see him.

All the adjectives that might be spilled cannot tell the story of the Green Mill Gardens as well as might a visit. Come any night. It will be a wonderful night when you come.41

The 1917 Automobile Blue Book recommended three “Outdoor Restaurants and Amusement Places” as places to visit in Chicago: Bismarck Gardens, Edelweiss Gardens (formerly known as Midway Gardens), and Green Mill Gardens. The travel guide described this trio as the “Principal Summer Gardens of the City.”42

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Footnotes

1 “The Green Mill— and Chamales,” Reform Advocate, July 29, 1916, 899. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015028004888?urlappend=%3Bseq=909%3Bownerid=13510798900635327-965

2 Document 7048590, Book 16543, 500-510, lease agreement between Catherine Hoffman and Tom Chamales, February 28, 1913, recorded January 28, 1921, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division, 500-505.

3 1913 Chicago city directory, 565, Fold3.com.

4 Document 7048590, 508.

5 Tract book 543 A-2, 249, 252, 253, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

6 “Taking Bids,” Construction News 35 (March 15, 1913): 14. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433090820436?urlappend=%3Bseq=344%3Bownerid=27021597770176289-348.

7 Document 7048590, 502.

8 “Oscar W. Rosenthal,” New York Times, October 3, 1943, 48.

9 “New Building Code May Be Ready in July,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 17, 1932, part 2, 13.

10 1914 Chicago city directory, 1385, Fold3.com.

11 Document 5382042, Book 12722, 560-561, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

12 Letter signed “J.D.,” to “In the Wake of the News” column, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 21, 1924, 11.

13 1891 Chicago city directory, 1081, Fold3.com.

14 Trav S.D., “J.W. Kelly ‘The Rolling Mill Man,’” Travalanche, September 1, 2011, https://travsd.wordpress.com/2011/09/01/stars-of-vaudeville-340-j-w-kelly-the-rolling-mill-man/.

15 J.W. Kelley, “When Hogan Paid His Rent,” (New York: Frank Harding, 1891). Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.100007145/.

16 1910 U.S. Census, Illinois, Cook, Chicago Ward 25, enumeration district 1054, sheet 16B; 1920 U.S. Census, California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles Assembly District 63, Enumeration District 0149, Sheet 6B; 1904 birth record of Josephine Stewart Butterly, Cook County, Illinois, U.S., Birth Certificates Index, 1871-1922, Ancestry.com.

17 Letter signed “J.D.,” to “In the Wake of the News” column, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 21, 1924, 11.

18 Chicago city directories, 1898–1909, Fold3.com.

19 1911 city directory, 253, Fold3.com.

20 Document 5382042.

21 Permit 20109, file 55525, Feb. 16, 1914, Chicago Building Permit Ledgers Reel UID CBPC_LB_14 246 (original 177), Chicago Building Permits Digital Collection 1872-1954, University of Illinois at Chicago Library.

22 Julia Bachrach, “Michaelsen & Rognstad: Architects of Fanciful Jazz Age Buildings,” Julia Bachrach Consulting, November 1, 2019, https://www.jbachrach.com/blog/2019/10/31/michaelsen-amp-rognstad-architects-of-fanciful-jazz-age-buildings; Laurie McGovern Petersen, ed., AIA Guide to Chicago, Fourth Edition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2022), 126-127, 243, 346.

23 Permit 20109.

24 Journal of the Proceedings of the City Council of the City of Chicago, Illinois, vol. 74, March 16, 1914, 4418, https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofcit74chic/page/4418/mode/2up.

25 Permit 20109, file 55525, February 16, 1914, Chicago Building Permit Ledgers Reel UID CBPC_LB_14 246 (original 177), Chicago Building Permits Digital Collection 1872-1954, University of Illinois at Chicago Library, https://researchguides.uic.edu/CBP.

26 Permit 222569, file 64827, June 10, 1914, Chicago Building Permit Ledgers Reel UID CBPC_LB_15 p. 26 (original p. 47).

27 “Della Robbia Room, Vanderbilt Hotel—1912,” Geographic Guide, accessed June 7, 2023, https://www.geographicguide.com/united-states/nyc/antique/hotels/vanderbilt/della-robbia.htm.

28 Advertisement, Chicago Examiner, June 13, 1914, 11.

29 Permit 20109, file 55525, February 16, 1914, Chicago Building Permit Ledgers Reel UID CBPC_LB_14 246 (original 177).

30 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 26, 1914, 4.

31 Robert Ebisch, “Whatever Happened to the Green Mill,” Chicago Reader, October 29, 1982.

32 1917 Chicago city directory, 338, in Fold3.com’s collection of pages from undated city directories. This matches the number of a page that’s missing from the 1917 Chicago city directory at Ancestry.com.

33 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 26, 1914, 4.

34 “Ralph Herz,” Internet Broadway Database, accessed June 7, 2023, https://www.ibdb.com/broadway-cast-staff/ralph-herz-23515.

35 Advertisements, Chicago Daily Tribune, October 11, 1914, November 11, 1914.

36 1914–1917 Chicago city directories, Fold3.com.

37 1915 Chicago city directory, at Fold3.com.

38 “Chicago News,” New York Clipper, June 5, 1915, 34. https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=NYC19150605.2.155&srpos=7&e=——-en-20–1-byDA-img-txIN-%22green+mill+gardens%22———.

39 “Green Mill Garden,” Chicago Daily News, July 10, 1915, 19.

40 Advertisement, Chicago Daily News, July 3, 1915, 16.

41 Reform Advocate.

42 Robert Wolfers, Official Automobile Blue Book, Vol. C, 1917 (Chicago: Automobile Blue Book Publishing), 40, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015069273673?urlappend=%3Bseq=42%3Bownerid=13510798886890370-48.