Chapter 13 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Chicago is famous for many kinds of music, but the blues may be the first genre that comes to mind when people think of music from the Windy City. Chicago can’t really claim to be the birthplace of the blues, but it was arguably the key place where the musical style flourished in the mid-20th century, as Black musicians carried it north during the Great Migration.

Chicago is also where the blues was used for the first time to describe the genre, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. Remarkably, the earliest known publication of this phrase as a musical term is also the first known article about jazz music: “Blues Is Jazz and Jazz Is Blues” by Gordon Seagrove, published by the Chicago Daily Tribune on July 11, 1915.1

Of course, Seagrove surely didn’t coin the blues as a musical term, just as he didn’t create the word jazz.

How did it happen that the blues and jazz were both bubbling into Chicago’s vocabulary at this same moment in 1915? Let’s take a look at the etymology of the blues, as well as the music’s origins.

Songs had already been published with the word blues in their titles, including 1901’s “I’ve Got de Blues” by the Black vaudeville team of Chris Smith and Elmer Bowman,2 1908’s “I Got the Blues” by Antonio Maggio,3 and 1909’s “I’m Alabama Bound (also known as the Alabama Blues)” by Robert Hoffman.4

“Low spirits”

At first, song titles like this didn’t refer to the blues as a musical genre. Rather, these musicians were talking about the blues in another sense: “Feelings of depression or melancholy; low spirits, despondency,” to quote OED’s definition.

This was a common theme in African American folk songs. And as time went on, “several melancholic songs began to include blues in their titles, leading to the adoption of the word as the name of the genre,” OED explains.5

The concept of the blues as slang for melancholy may derive from an expression dating back to the 15th century: blue devil, meaning “A harmful or malignant demon, especially one that causes melancholy.”6

As music historian Peter C. Muir notes, the word blue could refer to what might be perceived as two different colors: a “livid or blackish blue,” or the lighter hue that’s the color of the sky. The darker sort of blue was associated with discolored skin, like bruises. “Blue is the color skin turns after receiving a blow,” Muir writes.7 And that may have something to do with the reason why sad people were described as blue.

In a 2017 Sewanee Review article, John Jeremiah Sullivan pointed out how blue had been floating around as a musical term since the 1870s:

… in the decades just before people started to talk about singing “the blues” or “blues,” Americans were talking extensively about “blue music” and “blue songs.” It began in the 1870s, which is to say it began just after the Civil War, as freed slaves fanned out through the country by the tens of thousands. Emancipation was among other things a great cultural explosion and diffusion. People everywhere now were hearing, as they hadn’t really done before, the sounds of the plantation, the true black music, the moan. For most white American ears, especially in places where there had been no slavery, this sound was jarring and hypnotic. They called it “‘weird’”—always that word, never “strange” or “odd”—and they called it “blue.” It was sad and sexy, which were their two main connotations for “blue.”8

Blue notes

In Seagrove’s 1915 article, he also used blue as a word to describe a “sour” note, an element that he believed was the defining quality of both blues and jazz music. OED defines blue note as: “an incorrect or off-pitch note; (hence) an uncharacteristic or unexpected minor interval or flatted note in a musical phrase, typically a minor third, flat fifth, or flat seventh, especially as used in jazz and blues.”9

The first known example of anyone writing about a blue note is a Kansas City Times article from 1895 about an African American musical group performing in the show In Old Kentucky at the Grand Theater. The newspaper remarked: “At the beginning of their career, it will be remembered, they found difficulty in keeping their instruments out of ear-splitting mischief. In the language of the ‘profesor’ they struck many a ‘blue” note.’”10 (The group’s unfortunate name included an offensive term for Black children: It was the Woodlawn Wangdoodle Pickaninny Band.11)

In March 1915, a few months before Seagrove’s Tribune article, the Atlanta Constitution used blue note in a more flattering sense. Describing an orchestra performing W.C. Handy’s 1912 song “The Memphis Blues,” the newspaper commented: “The lank trombone, shot full length unburdens its pent-up soul and sobs to high heaven the unspeakable agony of the famous ‘blue note!’”12

A Chicago Daily News writer offered this explanation in 1917 for how the term blues had evolved: “The word ‘blues’ comes from a term given by musicians of bands to false tones. When one of the band struck a false or bad tone his associates would accuse him of having played a ‘blue’ tone. Finally, they introduced ‘blues’ into their pieces purposely to give them a sort of grotesque sound and now there are compositions called ‘blues.’”13

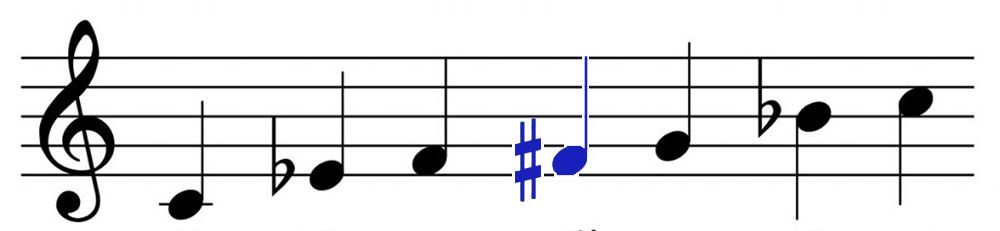

But this whole notion that musicians accidentally hit “bad” notes seems to be rooted in the way some people perceived what they were hearing. Musicians may have simply been using what we now call a blues scale—a set of notes different from those in Europe’s traditional major and minor scales.

For example, a musician playing in the hexatonic blues scale will use a sharp fourth. If C is the root note, that’s an F sharp.14 To someone who’d never heard blues, that note may have sounded wrong—but that doesn’t mean the musician played it in error.

That F sharp is jammed right in between two of the notes that make the most harmonious sounds when they’re played together with C: It’s half a step higher than F, which forms an interval called the perfect fourth when it’s played with C. And it’s half a step lower than G, which forms an interval called the perfect fifth when it’s played with C.

Those harmonious intervals—the perfect fourth and the perfect fifth—became the foundation of the European musical scale after the ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras noticed how beautiful they sounded. He also noticed a special resonance of tones separated by a distance called the octave.

Those harmonious intervals—the perfect fourth and the perfect fifth—became the foundation of the European musical scale after the ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras noticed how beautiful they sounded. He also noticed a special resonance of tones separated by a distance called the octave.

You can hear these intervals in two of the 20th century’s most beloved popular songs: The main melody of Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg’s “Over the Rainbow” begins with the word “Somewhere” jumping an octave between the first and second syllables. Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer’s “Moon River” takes a somewhat less startling leap after the opening word “Moon,” going up a perfect fifth for “Ri–,” before stepping down to a note that’s a perfect fourth above where the melody started, as it completes the word: “—ver.” For another example of the perfect fourth, listen to the jump between the first two notes of “Auld Lang Syne.”

According to legend, Pythagoras heard these intervals when he was passing by a blacksmith’s shop. The story is almost certainly apocryphal, but it helps to illustrate how people in ancient times heard sounds in the world around them and began developing a system for making music out of those noises. Here’s how Stuart Isacoff tells the legend in his 2001 book Temperament: The Idea That Solved Music’s Greatest Riddle:

Various hammers striking against anvils were creating a disordered, clanging chorus. Every so often, however, the reverberant clatter would seem to soften and blend into a mellifluous union. Pythagoras was determined to uncover the source of this phenomenon, and he entered the shop to observe.

The hammers were of different weights, and it turned out that each generated its own distinct tone. We can imagine Pythagoras watching as the heavy tools swung against their targets; one instant they produced a raucous mess, the next, a resonant choir. Finally, it dawned on him: Whenever the relative weights of the hammers striking the anvils formed certain simple ratios—when their heavy heads were found to be in the proportions 2:1 or 3:2 or 4:3—the notes they produced together created the most marvelous harmonies: sweet, bell-like, and exquisite.

While that story seems to be a myth, Pythagoras did conduct experiments using differing lengths of string to create vibrations of varying frequencies. “Pythagoras’s string experiments created the very foundation of musical art for thousands of years of Western civilization,” Isacoff writes.

Over the centuries, people tried to create a sequence of notes that included the perfect fourth, the perfect fifth, and the octave. Europeans more or less accomplished that goal by using equal temperament, which divided up an octave into 12 evenly spaced notes.15

That system gives musicians the possibility of playing those blues notes. If musicians struck a C note together with an F sharp, that combination of tones was considered so disconcerting that it was known for centuries as diabolus in musica, or the Devil’s Interval.

Legends about singers being excommunicated from the Catholic Church or punished for playing this combination of notes, also known as a tritone, may be apocryphal, but European composers and musicians had a long history of avoiding the tritone—believing it sounded unpleasant if not downright demonic.16

If Pythagoras heard this combination of tones at that mythical blacksmith’s shop, he would’ve considered it a discordant clash.

And yet, the two notes sat together in the blues scale.

Some musicologists believe that blues scales originated in African music, which enslaved people brought with them to America, where the music evolved.17 According to Britannica, the blues scale “is neither particularly African nor particularly European but acquired its peculiar modality from pitch inflections common to any number of West African languages and musical forms.”18

It’s unclear why these tones were called blue notes. The phrase existed before the genre was known as the blues, but perhaps the notes were associated with “blue music” in the late 1800s. Or maybe the notes themselves somehow reminded people of the color blue, or the sadness known as blues.

Music as a cure

In the late 19th century, when people with depression were described as having “the blues,” music was sometimes described as a cure for this ailment. The earliest example found by historian Peter Muir is an 1879 song, “Billy’s Request,” by Billy Birch and W.F. Wellman Jr., white entertainers who performed in blackface as members of the San Francisco Minstrels. The song’s title page calls it “A Cure for the Blues.” This was not a blues song, however—it was a lighthearted pop ditty.19

So, when was the first time someone suggested that blues music itself could work as a cure for the blues? According to Muir, the earliest known example of this idea in print is that same 1915 Tribune article by Gordon Seagrove. “That is what ‘blue’ music is doing for everybody—taking away what its name implies, the blues,” Seagrove wrote.20

By the time Seagrove’s article appeared, more songs had appeared with “blues” in their title. Muir points to “The Blues,” written by African American musicians Chris Smith and James T. Brymn, as the first true blues song, published on January 12, 1912. In his book Long Lost Blues, Muir writes:

Although essentially a ragtime song, “The Blues” contains much that is blues-related. The basic scenario—a woman grieving for her lover, who has deserted her—is typical of the genre. The most telling moment is at the beginning of the chorus, when the singer declares, “I’ve got the blues, but I’m too blamed mean to cry,” a variant of a line much used in folk blues and first found in a field transcription published the year before this song appeared.21

Four more songs were copyrighted or published later in 1912 with the word “blues” in their titles:

“Baby Seals Blues” by Franklin Seals (August 3).

“Dallas Blues” by Hart Wand (August 6).

“The Memphis Blues” by W.C. Handy (September 27).

“Negro Blues” by Le Roy “Lasses” White (copyrighted on November 6, 1912, but not published until 1913, with the N-word replacing “Negro” in the title). 22

And these songs inspired even more. According to Muir, four blues songs were published in 1913, followed by another 12 in 1914, and 21 more in 1915. 23

“The popularity acquired by compositions like ‘Baby Seals Blues’, ‘Dallas Blues’, and ‘Memphis Blues’ caught the attention of an ever increasing group of black and white composers, lyricists, publishers and musicians,” Erwin Bosman wrote in a No Depression article. “Blues became a craze, and crossed over into the white music culture, to such an extent that the epithet ‘blues’ in a song’s title often acted as a pure marketing instrument.” 24

The Freeman, a Black newspaper based in Indianapolis, called Virginia Liston “a ‘blues’ song singer” on June 7, 1913.25 Was the newspaper using blues to describe her style of music? Or was it just referring to the fact that Liston sang songs with titles using the word blues?

On November 10, 1913, sheet music of W.C. Handy’s “The Memphis Blues” was published with new lyrics by George A. Norton.26 Muir observes:

George Norton’s lyric is among other things a paean to the power of blues. The chorus describes both the emotional playing of Handy’s band (the bassoonist moans “just like a sinner on Revival Day”) and its strong effects on the listener (“Here comes the very part / that wraps a spell around my heart. / It sets me wild / to hear that lovin’ tune again”); similarly, the second verse refers to the lasting effect of the experience on the listener (“[I] simply can’t forget that blue refrain”). While the lyric stops short of actually stating that blues music cures the blues, it strongly implies it. 27

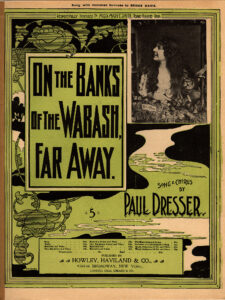

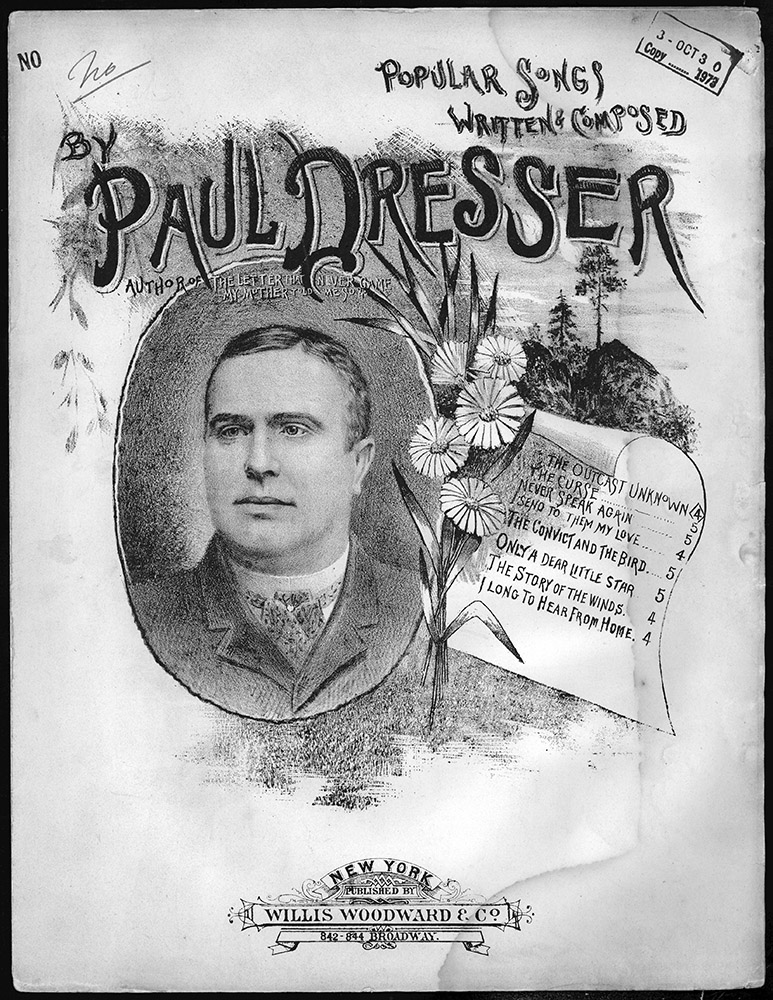

Paul Dresser, bluesman?

Another key moment in the evolution of the word blues was November 7, 1914, when the Chicago Defender published an article by African American arts critic Columbus Bragg. He declared: “Mr. William Abel, the race’s greatest descriptive singer, will sing the first Blues song, entitled ‘Curses,’ by Mr. Paul Dresser.”28

The Oxford English Dictionary cites this article as the first known example of anyone using blues as a term “designating a song, melody, etc., performed in a blues style.” 29 It’s also noteworthy that this composition was described as a blues song even though its title didn’t include the word blues.

But Bragg’s statement about “the first Blues song” was rather curious. For one thing, the blues is unquestionably rooted in African American music and traditions, and Paul Dresser was white.

But Bragg’s statement about “the first Blues song” was rather curious. For one thing, the blues is unquestionably rooted in African American music and traditions, and Paul Dresser was white.

A Hoosier of German heritage who’d performed in minstrel shows wearing blackface early in his career, the showman was a celebrity before his younger brother Theodore Dreiser, a journalist who worked in Chicago, gained fame as he used the city as the setting for bestselling novels.

“On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away,” Dresser’s biggest hit, was one of the 19th century’s top-selling pieces of sheet music, and it was later designated as Indiana’s official state song. Although Dresser was closely associated with his hometown of Terre Haute, he regularly appeared on Chicago stages.

He reportedly weighed more than 300 pounds,30 and his girth was part of his public persona. The Inter Ocean called him “the fat comedian and composer of a number of popular songs,”31 later offering this commentary on a performance: “Paul Dresser … is fat but active, but his conception of what is funny is somewhat peculiar, to put it mildly.”32

The other curious thing about that statement in the Defender is the nearly total obscurity of the song it described as “the first Blues song.” It wasn’t until 2017 that the song was properly identified, when Sullivan traced its history in a marvelous two-part series for Sewanee Review.

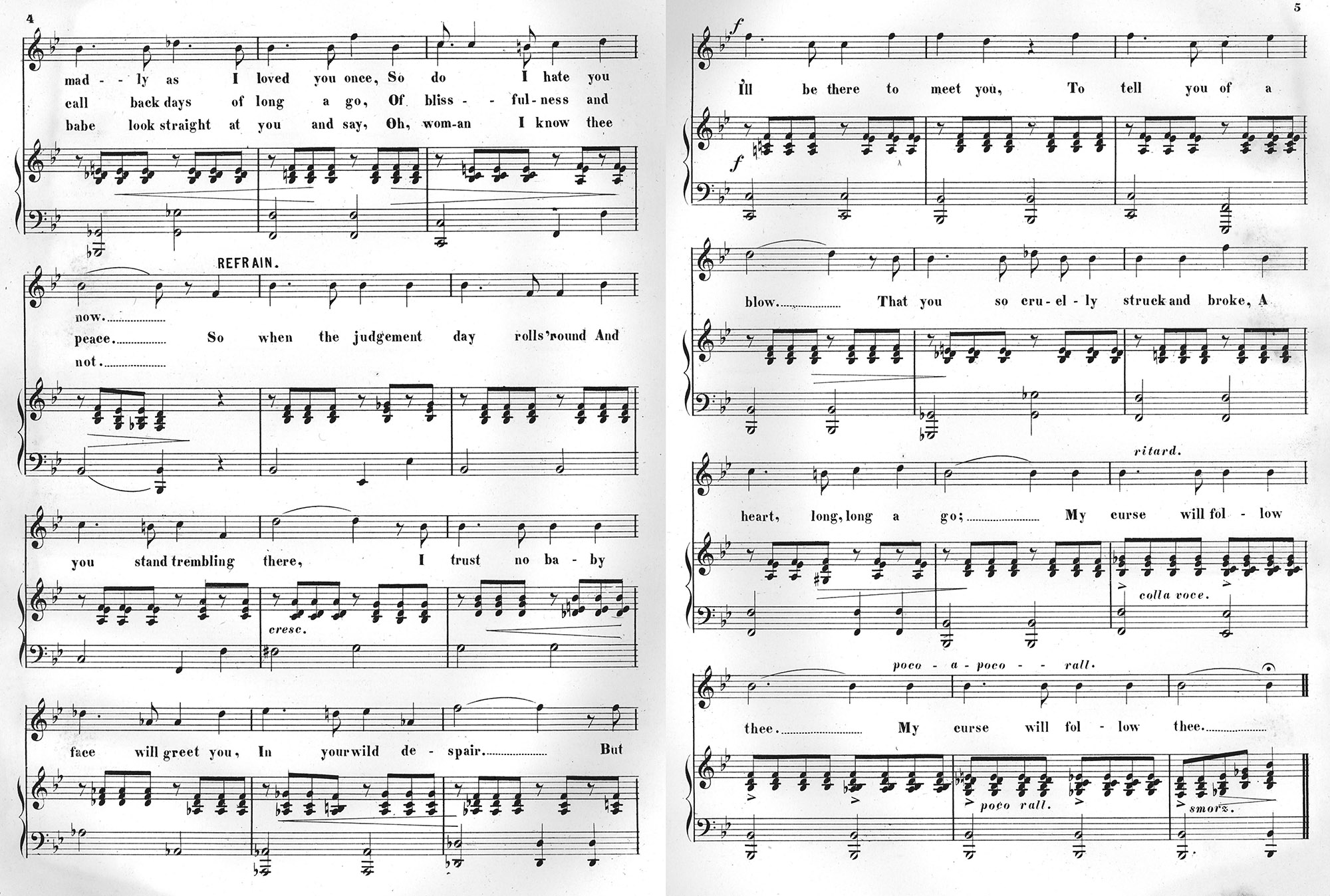

Sullivan’s research revealed that the song was actually “The Curse,” which Dresser published in 1887, a bitter denunciation of singer May Howard, “the Queen of Burlesque” (the sister of notorious Chicago saloonkeeper and thief George Havill33), following their breakup.

Dresser wrote the song after their infant child died and May left him for another man.34 But he later withdrew the song from circulation, so the sheet music became almost unavailable.

“It is a profoundly weird and terrible song. Terrible in the sense of terror,” Sullivan wrote after finding the sheet music in the collection of the Library of Congress. “… The words gave off the seared-flesh smell of true brokenheartedness and its scarring resentments. It was like nothing I would expect to hear in 1887. … Not this violent and personal.”35

There’s a legend that Dresser performed the song one time when May was sitting in the audience, addressing the lyrics directly to the woman who’d provoked them:

So when the judgment day rolls ‘round and you stand trembling there

I trust no baby face will greet you in your wild despair;

But I’ll be there to meet you, to tell you of a blow

That you so cruelly struck, and broke a heart, long, long ago;

My curse will follow thee.

My curse will follow thee. 36

Dresser’s performance was reportedly interrupted by “a piercing scream which brought the audience to its feet, and May Howard was carried out insensible.”37

Dresser denied that this story was true, but he had his own hair-raising tale about the song’s effect: Someone had supposedly shot another singer performing “The Curse” in Boston. Consequently, Dresser believed that “The Curse” was cursed, and so he refused to sing it.38

Despite his fame and success, Dresser died, reportedly penniless, in New York City in 1906. His remains were taken in 1907 to Chicago’s St. Boniface Cemetery, where he was buried next to his parents.

His grave was unmarked until 1922,39 when the Indiana Club of Chicago, a social organization for Hoosiers living in the Windy City,40 brought a boulder from the banks of the Wabash River and had it engraved with his name. May Howard, the woman he’d cursed in his notorious song, reportedly visited the grave in 1923.41

As it happens, the boulder covering Paul Dresser’s burial place is just 1,000 feet west of the Green Mill. The engraving on the rock mentions “On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away,” but—of course—it’s silent about “The Curse.”

It’s a stretch to call “The Curse” a blues song. It doesn’t appear that anyone recorded it until 2017, when Sewanee Review posted a (not very bluesy) rendition. In the years between 1887 and 1914, did other musicians transform Dresser’s tune into something more like the blues? Perhaps, but we can only guess.

Another song by Dresser, “My Gal Sal,” became popular in New Orleans around 1906 and 1907, according to Jelly Roll Morton, who jazzed it up. (My Gal Sal is also the title of a 1942 movie about Dresser.42)

Another song by Dresser, “My Gal Sal,” became popular in New Orleans around 1906 and 1907, according to Jelly Roll Morton, who jazzed it up. (My Gal Sal is also the title of a 1942 movie about Dresser.42)

I wonder if the mystique surrounding “The Curse”—the legends about how it seemed to be cursed—may have turned it into a cult classic, performed by musicians who wanted to be daring and transgressive? In any case, it’s a mystery how it came to be performed in Chicago in 1914.

Although Paul Dresser is an unlikely candidate for an originator of the blues, it’s noteworthy that a Black critic, Columbus Bragg, wrote in a Black newspaper about a Black musician, Will Abel, performing Dresser’s composition as “the first Blues song.” As Sullivan observed, Bragg “was on the minstrel circuit pretty much nonstop between 1892 and 1904. If anybody was present for the Big Bang of the blues, it was Bragg.”43

If nothing else, the story of “The Curse” may offer an example of how African American musicians sometimes pulled material from white songwriters and performers—who, of course, had themselves taken from African American music and culture.

String Beans, an early blues star

Music historians Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff traced how the blues emerged out of the African American vaudeville theater movement in the first years of the 20th century, when some theaters began offering Black entertainment for Black audiences.

Music historians Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff traced how the blues emerged out of the African American vaudeville theater movement in the first years of the 20th century, when some theaters began offering Black entertainment for Black audiences.

Those venues included the Pekin Theatre on Chicago’s South Side. When Robert Motts opened it in 1906, an advertisement called it “The only first-class and properly equipped theatre in the United States, owned, managed and controlled by colored promoters.”44

African Americans clearly took pride in the fact that a Black man owned the Pekin, but after Motts died, two white businessmen—Tom Chamales and Frank Haight—leased the theater in 1912. The Pekin’s Black stage manager, Will H. Smith, predicted that it would “thrive in the white people’s hands,” adding: “As everything on State st. is owned by whites they will get all that the colored people spend.”45

And a local Black newspaper, the Broad Ax, called Chamales “one of Chicago’s most enterprising and progressive business men,” remarking: “Mr. Chamales has the reputation of going the limit where there is a possible chance to break even in a financial footing, and we are proud that the Pekin is in such experienced hands as Messrs. Chamales and Haight and we welcome them to be among us and heartily endorse the Pekin as the Amusement House of the People.”46

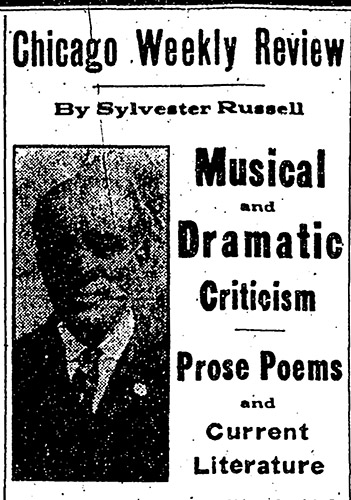

But Haight and Chamales ran the Pekin for just a couple of months.47 A legend spread that the Pekin was haunted by the ghost of Robert Motts, as Sylvester Russell, an African American arts critic in Chicago, wrote in the Freeman:

Every time the house would open under white management, the curtain would always hitch, without fail, in the first performance. … After “The ghost of Motts in the curtain” rumor had made its record of fame among the gods, I would take a seat in the gallery among the working boys, unrecognized, and apparently without notice, just to hear the boys comment and enjoy themselves while waiting for the show to commence and see the curtain hitch. The boys would assert that they came to see Motts hold the curtain. And, sure enough, the curtain hitched.48

In their 2017 book The Original Blues, Abbott and Seroff described this era of entertainment for Black audiences:

Performers were far more “at home” in the absence of white folk; and audiences were validated by authentic representations of African American music and culture. Vernacular expressions and coded references excited howls of recognition, encouraging performers to dig deeper in the storehouse of shared cultural experience. This emboldened the coming generation of stage performers to unleash creative energies that accelerated the development of the blues.49

“The earliest known account of blues singing in black vaudeville, and even of any kind, is contained in a black journal article in April 1910, reporting on a show at the Airdome Theater in Jacksonville, Florida,” Bosman wrote in No Depression. “The article comments on a stage show where Henry, the dummy of ventriloquist John W.F. Woods gets drunk, and where he uses ‘blues’ for the dummy Henry in this drunken act.”

According to Muir’s book Long Lost Blues, “After that, reports of black vaudeville became increasingly common, and by 1912, less than two years later, blues had become a ‘rampant’ phenomenon.” 50

Butler “String Beans” May did more than anyone else to popularize blues music during these formative years, according to Abbott and Seroff. 51 The Chicago Defender commented that “there probably was no better known performer to race vaudeville fans than Butler May.”52

Born in Montgomery, Alabama, in the early 1890s,53 the tall, skinny piano player and comedian frequently performed between 1911 and 1917 at Chicago’s Monogram Theatre, 3028 South State Street, and New Monogram Theatre, 3461 South State Street.54

Born in Montgomery, Alabama, in the early 1890s,53 the tall, skinny piano player and comedian frequently performed between 1911 and 1917 at Chicago’s Monogram Theatre, 3028 South State Street, and New Monogram Theatre, 3461 South State Street.54

Those theaters were owned by a white Jewish South Sider, Martin Klein, whose parents were immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He had a reputation for supporting the Black community and booked “almost exclusively colored performers.” 55

But the Monogram was far from luxurious. “Of all the rinky-dink dumps I played, nothing was worse than the Monogram Theater in Chicago,” singer Ethel Waters recalled. “It was close to the El, and the walls were so thin that you stopped singing—or telling a joke—every time a train passed.”56

When String Beans made his Chicago debut at the Monogram in May 1911—performing together with his wife and stage partner, Sweetie May—it was the first known time Black vaudeville artists had ventured out of the South to perform the nascent style of music that was becoming known as the blues in front of an audience in the North. Abbott and Seroff describe this as the moment when the Mays “headed for Chicago to introduce the blues.”57

Sylvester Russell, the Freeman’s critic, described how audiences went wild for String Beans, though Russell didn’t always grasp what was appealing about the music.

“Whatever it is that May hands over, nobody knows, or cares, but it thrills and creates riots of laughter,” he wrote.58 Russell (whom Abbott and Seroff described as “strait-laced and snobbish”59) later accused String Beans of performing “smut” and songs that “only appeal to colored people.”60

String Beans said he’d refused to pay off Russell to get good reviews, alleging: “He is not a critic. He is simply a money receiver.”61

Black audiences didn’t need Russell’s approval to enjoy what they saw and heard at String Beans’ concerts. Another writer for the Freeman reported that “the yelling was almost deafening” at String Beans’ shows.

“His ‘Blues’ gets ’em,” the newspaper wrote in January 1914, the first time anyone had used blues to describe his music. “… The audience screams for more, and he give them more.”62

Describing String Beans performing one of his signature tunes, “The Sinking of the Titanic,” the Freeman commented: “His knowledge of minor chords, chromatic scales, enabled him to give a weird, terrifying effect when the vessel went down.”63

Decades later, musician and educator Willis Laurence James remembered what it was like to see String Beans in concert:

“Standing at full height, he reaches down to the keyboard as he sings like an early Ray Charles. … As he attacks the piano, Stringbeans’ head starts to nod, his shoulders shake, and his body begins to quiver. Slowly, he sinks to the floor of the stage. Before he submerges, he is executing the Snake Hips …, shouting the blues and, as he hits the deck still playing the piano performing a horizontal grin which would make today’s rock and roll dancers seem like staid citizens.”64

“If he was not recognized by his contemporaries as the first great piano blues man or the first blues king, it was only because there was nobody to compare to,” Bosman commented in No Depression. “… While W.C. Handy represented the ‘respectful’ blues, Butler May personified the unadulterated, pure instinct of the blues.” 65

One of the few surviving images of Butler May is a cartoon, published by the Freeman on May 16, 1914. Although it was printed in an African American newspaper, it used stereotypical imagery that many people might find offensive today.

Butler “String Beans” May’s career came to an abrupt and tragic end when he died on November 17, 1917, after his neck was broken during a hazing ritual at a Freemason lodge for African Americans he was joining in Jacksonville, Florida.66

“It is … probable that the initiation rite derailed when a rope was put around his neck as part of a ceremony that reminds the candidates of their humble and fragile state,” Bosman wrote.67

May, who was still in his 20s, hadn’t made any recordings or copyrighted any songs during his life, but other performers adapted many of his songs, according to Abbott and Seroff.68

Robert Johnson later sang about “Elgin movements” in “Walking Blues,”69 alluding to one of String Beans’ most popular numbers, “I’ve Got Elgin Movements in My Hips, With a Twenty Year Guarantee,” which was inspired by advertisements for pocket watches manufactured in Elgin, Illinois.70

“The Blues,” which Muir describes as the first published blues song, may have been influenced by String Beans. One of the song’s cowriters, Chris Smith, had shared a bill with String Beans at Chicago’s Monogram Theater in May 1911. That was just a short time before Smith wrote the song with Tim Brymn.

“I would suggest that it was Smith’s exposure to String Beans’s sensational singing of the blues and its impact on northern audiences that inspired him to pen ‘The Blues’ with Brymn a few months later,” Muir writes.71

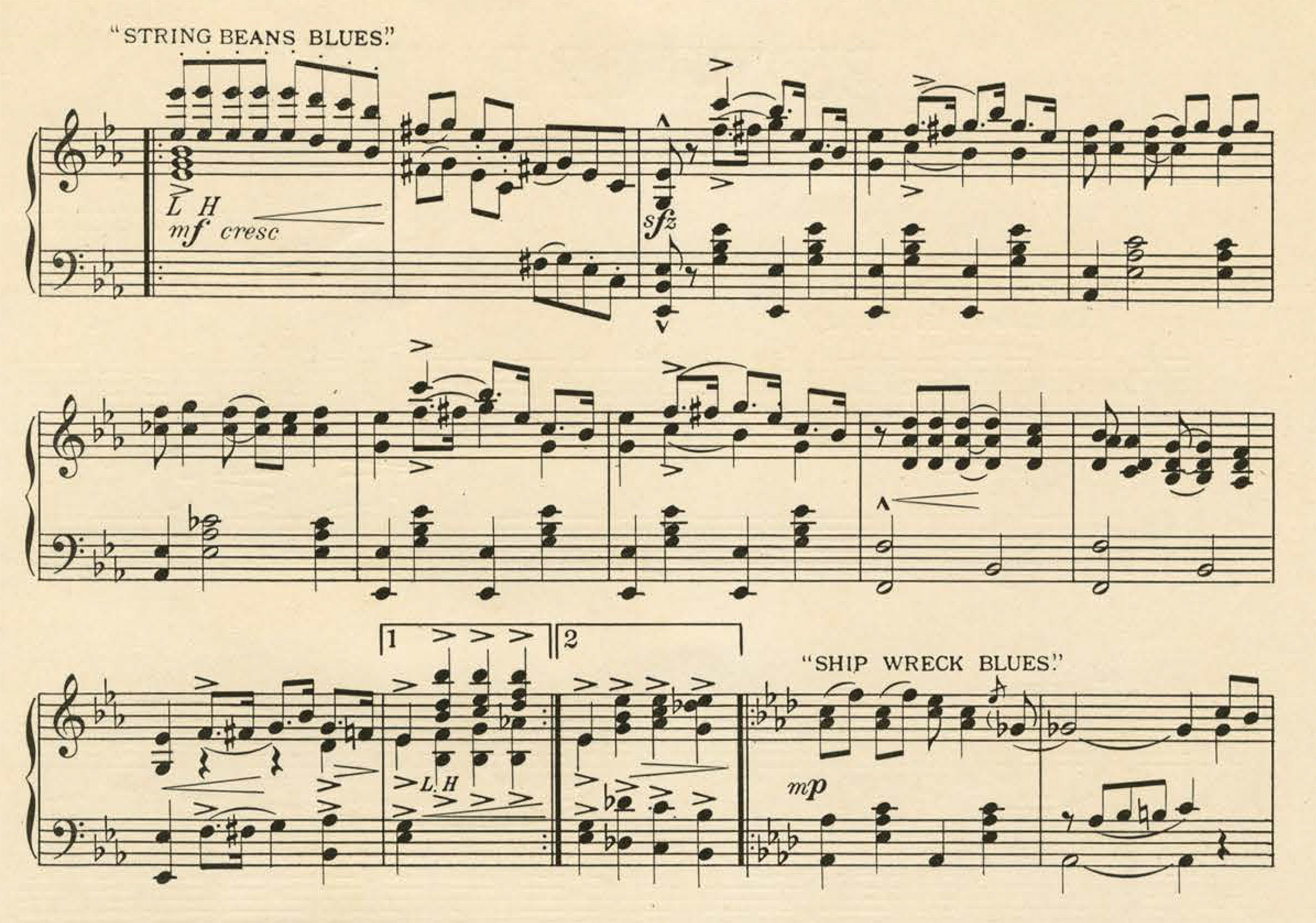

While String Beans was still alive, two Black Chicagoans, H. Alf Kelley and J. Paul Wyer, had published “String Beans Blues,” as part of a 1915 instrumental medley titled “A Bunch of Blues.”72

Wyer was a fiddler from Florida known as “The Pensacola Kid,”73 and Kelley was a lyricist who ran the Chicago Musical Bureau publishing company at 3159 South State Street in the Black Belt. They’d previously teamed up on writing the 1914 song “Long Lost Blues.”74

Although they didn’t credit “String Beans Blues” to Butler May, the title itself suggests he was the true author. (Here’s a 1923 recording of “A Bunch of Blues” by the Original Memphis Five.)

This motif, which Jelly Roll Morton later used and Blind Lemon Jefferson adapted for guitar,75 helped define the sound of the blues.

“It begins with eight (or six) identical staccato notes on the same pitch, then a half-beat pause, followed by a brief descending progression,” Abbott and Seroff wrote. “… Something about this deceptively simple, unprepossessing riff was identified as essentially blues.”76

When Gordon Seagrove wrote about blues music for the Tribune, he may have been clueless about what was happening in the Stroll, the Black Belt’s entertainment district. It’s doubtful he’d heard the raucous blues piano playing of String Beans—or that he even knew who String Beans was.

What about Seagrove’s conclusion that blues and jazz are the same thing? Music historians are still trying to piece together how blues and jazz evolved, and how they influenced each other. In a 1991 article, musicologist Paul Oliver summed up the various contradictory theories:

Blues was African in origin, it was not African in character, it was a rural music, it was a city music, it was part of the pre-history of jazz, it was an influence on the formation of jazz, it was part of a convergence phenomenon in the shaping of jazz, it was assimilated by jazz after its marching phase, it was played with ragtime before jazz bands played jazz, it was adopted by ragtime musicians at a later stage, it was, and is, the essence of jazz expression …77

In one way or another, early elements of blues and jazz music were trickling out of the Black entertainment scene around 1915 and finding their way into Chicago cabarets, where white audiences heard these startling sounds.

This concludes my trilogy of chapters about the origins and etymology of jazz and the blues, but there’ll be more about this topic sprinkled throughout upcoming chapters.

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Footnotes

1 Oxford English Dictionary, online version, March 2023.

2 Peter C. Muir, Long Lost Blues: Popular Blues in America, 1850–1920 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 185.

3 Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff, The Original Blues: The Emergence of the Blues in African American Vaudeville (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2017), 76.

4 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 75-76; “I’m Alabama Bound,” Wikipedia, accessed July 16, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I%27m_Alabama_Bound.

5 Oxford English Dictionary, online version, March 2023.

6 Oxford English Dictionary, online version, March 2022.

7 Peter C. Muir, Long Lost Blues: Popular Blues in America, 1850–1920 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 81.

8 John Jeremiah Sullivan, “The Curses: Part 1: Ahjah Is Coming,” Sewanee Review 125, no. 1 (winter 2017): 3, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26405691.

9 Oxford English Dictionary, online version, March 2023.

10 “In Old Kentucky,” Kansas City Times, December 10, 1895, 4.

11 Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff, Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889–1895 (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2002), 406-407.

12 Ned M’Intosh, “‘Honey Boy’ Minstrels Please Large Audience at Atlanta,” Atlanta Constitution, March 12, 1915, 12.

13 M.R., “About the Jazz Bands and Cabaret Music,” Chicago Daily News, November 17, 1917, 12.

14 “Blues Scale,” Wikipedia, accessed July 24, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blues_scale.

15 Stuart Isacoff, Temperament: The Idea That Solved Music’s Greatest Riddle (New Yor: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), 31-32.

16 “Tritone,” Wikipedia, July 24, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tritone.

17 Paul Oliver, “That Certain Feeling: Blues and Jazz… in 1890?” Popular Music 10, no. 1 (1991), 13. http://www.jstor.org/stable/853006.

18 Gunther Schuller, “Jazz,” Britannica, updated June 29, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/art/jazz#ref395907.

19 Muir, Long Lost Blues, 83-84.

20 Muir, Long Lost Blues, 86-87.

21 Muir, Long Lost Blues, 7.

22 Muir, Long Lost Blues, 9.

23 Muir, Long Lost Blues, 12.

24 Erwin Bosman, “Butler May: Was he the Real Father of the Blues?” No Depression, June 4, 2012, https://www.nodepression.com/butler-may-was-he-the-real-father-of-the-blues/.

25 “Gossip of the Stage: The New Crown Garden Theater,” (Indianapolis) Freeman, June 7, 1913, 5.

26 “The Memphis Blues,” Wikipedia, accessed August 6, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Memphis_Blues.

27 Muir, Long Lost Blues, 87.

28 Columbus Bragg, “Sacred Cantata at Bethel Church,” Chicago Defender, November 7, 1914, 6.

29 Oxford English Dictionary, online version, March 2023.

30 John Jeremiah Sullivan, “The Curses: Part 2: The Curse of the Dreamer,” Sewanee Review 125, no. 2 (spring 2017): 260, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26405754.

31 “General Mention,” Inter Ocean, March 13, 1895, 6.

32 “General Mention,” Inter Ocean, March 18, 1895, 3.

33 Sullivan’s article describes May as Havill’s daughter. That is contradicted by the information in these sources: Jerry Kuntz, “#15 Joseph Cook,” Professional Criminals of America (Revised), May 8, 2018, https://criminalsrevised.org/15-joseph-cook/; Loren Gatch, “A Theatrical Note About Burlesque,” Society of Paper Money Collectors Inc., July 24, 2020, https://www.spmc.org/blog/theatrical-note-about-burlesque.

34 Sullivan, “The Curses: Part 2,” 266-272.

35 Sullivan, “The Curses: Part 2,” 280-281.

36 Sullivan, “The Curses: Part 2,” 281.

37 Sullivan, “The Curses: Part 2,” 287.

38 Sullivan, “The Curses: Part 2,” 290.

39 “Paul Dresser,” Wikipedia, accessed July 22, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Dresser.

40 Indiana Society of Chicago, accessed July 16, 2023, http://www.indianasocietyofchicago.org/.

41 Sullivan, “The Curses: Part 2,” 291.

42 “My Gal Sal,” Wikipedia, accessed July 15, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/My_Gal_Sal.

43 Sullivan, “The Curses: Part 1, 17.

44 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 58.

45 Thomas Bauman, The Pekin: The Rise and Fall of Chicago’s First Black-Owned Theater (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014), 141. Cited source: Washington Bee, July 27, 1912, 1.

46 S.W.H., “The Pekin Theatre,” (Chicago) Broad Ax, August 10, 1912, 2.

47 Bauman, The Pekin, 141-142, 165.

48 Bauman, The Pekin, 142. Cited source: Freeman, August 19, 1916, 5.

49 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 3.

50 Bosman, “Butler May”; Muir, Long Lost Blues, 10.

51 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 73.

52 Bosman, “Butler May.”

53 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 67.

54 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 73. Addresses: Advertisement, (Indianapolis) Freeman, January 3, 1914, 6.

55 Michelle R. Scott, T.O.B.A. Time: Black Vaudeville and the Theater Owners’ Booking Association in Jazz-Age America (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2023), e-book, chapter 2, https://books.google.com/books?id=y5uoEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT38.

56 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 73.

57 Muir, Long Lost Blues, 10; Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 73.

58 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 74; Sylvester Freeman, “Chicago Weekly Review,” Freeman, May 27, 1911.

59 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 74; Sylvester Freeman, “Chicago Weekly Review,” Freeman, May 27, 1911.

60 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 79; Sylvester Freeman, “Chicago Weekly Review,” Freeman, September 7, 1912.

61 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 79; Butler May, “How to Get a Good Write Up,” Freeman, August 31, 1912.

62 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 82; “New Crown Garden Theater,” Freeman, January 24, 1914.

63 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 85; “At the New Crown Garden Theatre,” Freeman,May 16, 1914.

64 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 85. Cited source: Marshall and Jean Stearns, “Frontiers of Humor: African Vernacular Dance,” Southern Folklore Quarterly 30, no. 3 (September 1966): 228-229.

65 Bosman, “Butler May.”

66 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 112.

67 Bosman, “Butler May.”

68 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 115-116.

69 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 117.

70 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 69-70.

71 Muir, Long Lost Blues, 10-11.

72 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 120.

73 U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, Ancestry.com; “Paul Wyer,” Chicago Defender, June 26, 1923, 7.

74 “The Long Lost Blues,” Castle Ragtime, accessed July 16, 2023, https://castleragtime.com/ragtime-sheet-music/the-long-lost-blues; 1915 Chicago city directory, 859, Fold3.com; “A Note or Two,” Chicago Defender, May 22, 1915, 6.

75 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 121.

76 Abbott and Seroff, Original Blues, 120.

77 Paul Oliver, “That Certain Feeling: Blues and Jazz… in 1890?” Popular Music 10, no. 1 (1991), 18, http://www.jstor.org/stable/853006.