Chapter 12 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Around 1915, some musicians from New Orleans and San Francisco arrived in Chicago, where they started playing something called jazz. Did they bring that word with them? Or was Chicago the place where this word was applied to this style of music for the first time? That’s a mystery. There’s much debate about when exactly jazz became musical term.

Ferdinand “Jelly Roll” Morton, the legendary Creole pianist and composer, once said that he started using the word in New Orleans in 1902, “to show people the difference between jazz and ragtime.” But historians haven’t found evidence to back up his claim. Other New Orleans musicians said they never heard the word until years later.1

An exodus from New Orleans

“While the exuberant, syncopated performance style we now recognize as jazz was born in New Orleans, the music preceded its memorable name,” lexicologist Ben Zimmer wrote. “For New Orleans musicians of the time, what they played in their collective improvisations was simply a ‘hot’ variety of ‘ragtime,’ although that label was growing increasingly outdated.”2

Morton performed in Chicago during visits in 1910 and 1912, and he moved to the city in August 1914, staying for three years. His song “Jelly Roll Blues” was published as sheet music in Chicago in 1915, becoming “the first bona fide jazz composition available in score,” according to Howard Reich and William Gaines, authors of the book Jelly’s Blues.

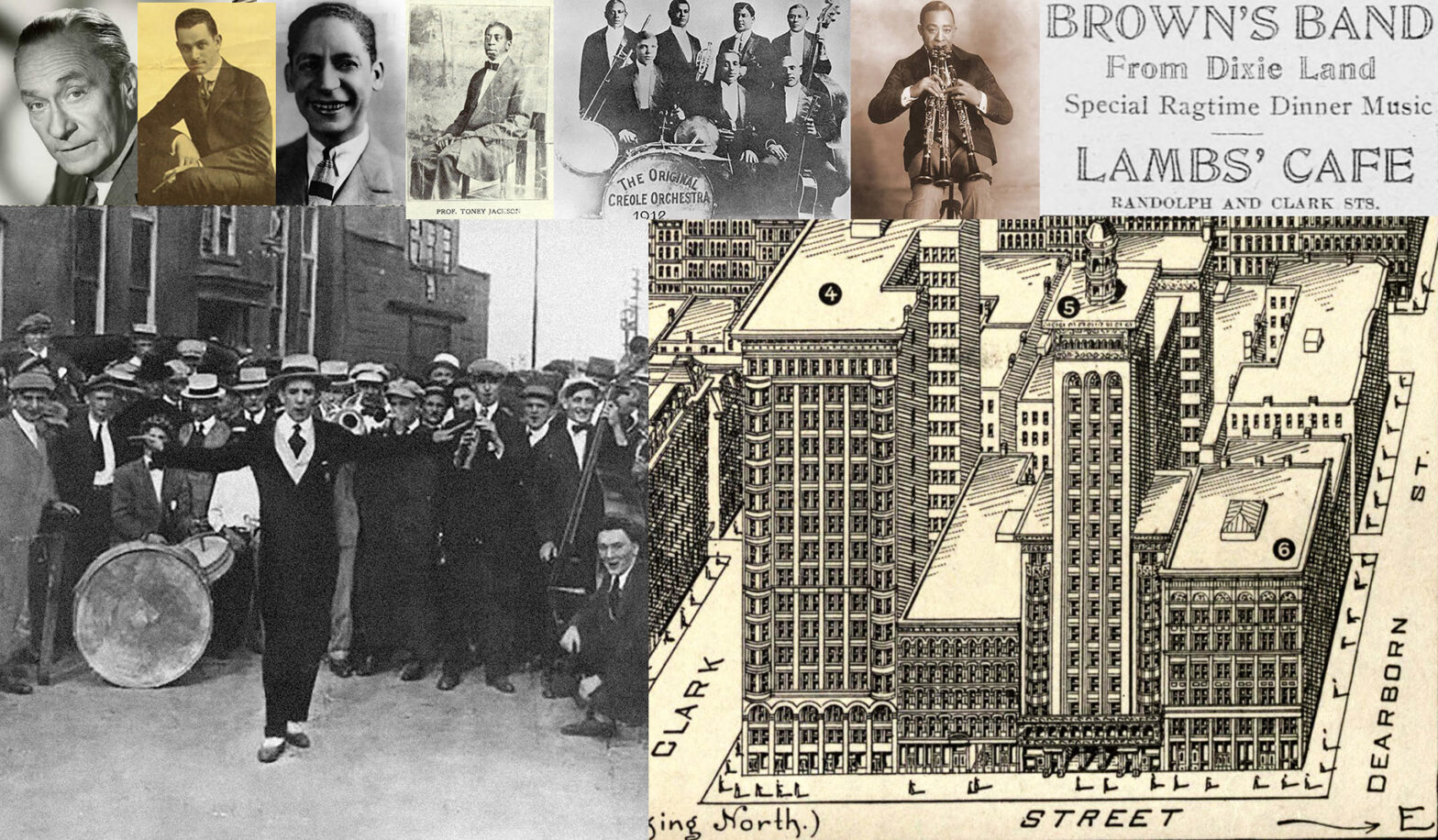

When Morton moved to Chicago, he was following in the footsteps of his friend Tony Jackson, a New Orleans pianist and singer who’d moved to the city in 1912 and had a hit with “Pretty Baby.”3 Another New Orleans expat, pianist Albert Carroll, was drawing crowds at the Pekin (where Green Mill Gardens’ Tom Chamales was part-owner for a time). The Original Creole Orchestra, featuring New Orleans cornetist Freddie Keppard, had also played shows in Chicago.4

And it wasn’t just New Orleans musicians who were making innovative sounds in the theaters and cabarets in Chicago’s Black Belt. Joe Jordan, who’d grown up in St. Louis, helped to lay the groundwork for jazz with his work conducting the Pekin Theatre’s orchestra.5 And Missouri native Wilbur Sweatman played hot syncopated tunes on clarinet—sometimes blowing into three clarinets simultaneously.6

Tony Jackson, the Original Creole Orchestra, and Wilbur Sweatman.

This scene was one of the places where jazz was born, emerging out of “a combination of folk blues, marching band tunes, social dance music, popular songs, and ragtime,” William Howland Kenney wrote in Chicago Jazz: A Cultural History, 1904–1930. But as he noted: “Most Chicagoans were only marginally aware of the complex and subtle details of African-American encounters with European music.”7

It’s unclear whether Black musicians on Chicago’s South Side called their music jazz during these early years. The Chicago Defender, the city’s leading African American newspaper, didn’t use the word or its variations until September 30, 1916—more than a year after the Chicago Daily Tribune first wrote about jazz.8

It wasn’t until the summer of 1917 that Louis Armstrong heard the word jazz uttered in New Orleans, according to Robert Goffin’s 1947 biography of the famed trumpeter. Armstrong recalled bandleader Joe Oliver showing him a letter he’d received from Freddie Keppard, who moved to Chicago around this time.

“Freddie reported that the new music known as ‘ragtime’ in New Orleans was called ‘jazz’ in Chicago, where it was creating a sensation,” Goffin wrote. “The expressive new term soon spread like wildfire in New Orleans and was applied indiscriminately played by white, Creole, and Negro bands.”9

As jazz continued booming in popularity across the country, the New Orleans Times-Picayune published an editorial on June 20, 1918, denouncing “jass” and rejecting the theory that this low-class “oddity” had originated in the Crescent City:

In the matter of jass, New Orleans is particularly interested, it has been widely suggested that this particular form of musical vice had its birth in this city—that it came, in fact, from doubtful surroundings in our slums. We do not recognize the honor of parenthood, but with such a story in circulation, it behooves us to be last to accept the atrocity in polite society, and where it has crept in we should make it a point of civic honor to suppress it. Its musical value is nil, and its possibilities of harm are great.10

But another newspaper, the New Orleans Item, proudly claimed in 1919 that the city was the birthplace of jazz: “It’s called ‘jazz,’ that synchronizing supersyncopation that, originating in New Orleans, has aggravated the foot and fingers of America into a shimmying, tickle-toeing, snapping delirium and now is upsetting the swaying equilibrium of the European dance.”

That article told a legend about a blind New Orleans newsboy nicknamed Stale Bread, who’d played fiddle as he sold newspapers back around the 1890s, eventually forming a group called Stale Bread’s Spasm Band. The Item suggested that jazz—the music and possibly the word—had evolved out of the Spasm Band.11 A similar tale appears in Herbert Asbury’s 1938 book The French Quarter, which says “the real creators of jazz” were some teenage boys calling themselves the Razzy Dazzy Spasm Band.12

Cornet player Ray Lopez remembered hearing the word jazz when he was working for the Orpheum Theatre in New Orleans, sometime before he got married in June 1912.

The man who uttered the word was William Demarest, an actor later known for his roles in Preston Sturges movies and the sitcom My Three Sons. At this time, he was playing cello as part of a comedy routine.

As Demarest explained a music cue to the show’s musicians, he said, “Jazz it up—loud and snappy.” Lopez later commented: “That was the first time I had ever heard the word used in connection with music.”13

Decades later, Demarest recalled learning the word jazz on the West Coast. He remembered hearing his brother George say, “Come on, jazz it up,” when they were in a band playing “Grizzly Bear Rag” at San Francisco’s Portola Theatre in May 1910.14 (See Chapter 6 for more about the dance craze associated with that song, which led to protests over the bathers dancing suggestively at Wilson Avenue Beach.)

The word jazz popped up in something like a musical context on June 28, 1913, when the Winnipeg Tribune (quoting an earlier San Francisco Bulletin review) described how the chorus in the stage show Hanky Panky “must have put the ‘J’ to ‘Jazz,’ for they teemed with pepper and ginger.”15

But the lexicologist Ammon Shea has said, “I don’t think that that was an actual reference to jazz music, but it does exhibit some kind of broadening out of baseball and to other fields and musical field.”16

Bert Kelly’s claim

Bert Kelly insisted that he was the first person to use the expression jazz band. The banjoist and band leader—whose full name was Albert R. Kelly—was originally from Cedar Rapids, Iowa, but he’d spent the first 18 years of his career performing on the West Coast, before making his way to Chicago around September 1914.17

“I conceived the idea of using the Far West slangword, ‘jazz,’ as a name for an original dance band and my original dance band and my original style of playing a dance rhythm at the College Inn, in 1914,” Kelly wrote in a 1957 letter to Variety.18

If Kelly’s story is true, then he could be the messenger who delivered the word jazz from the West Coast to Chicago.

But I haven’t found any Chicago newspaper articles or ads mentioning Kelly or his band before 1917.19 “The earliest surviving report calls Kelly’s outfit the Frisco Ragtime Four, but group names in this period were perversely fluid,” music historian Elijah Wald wrote.20

If Kelly did in fact play jazz at the Sherman Hotel’s College Inn in 1914 (the same year Gilbert “Broncho Billy” Anderson took Charlie Chaplin there on New Year’s Eve, as recounted in Chapter 9), it didn’t seem to attract any attention from the press.

A party at the Sherman Hotel

According to one story, Kelly’s big breakthrough came in 1915, when his band performed at a Sherman Hotel party for movie star Thomas Meighan. The Essanay movie studio’s Richard Travers reportedly filmed the musicians, including a title card in the resulting film that said: “The Originators of Jazz.”

Walter J. Kingsley told this story in a 1919 New York Sun article. “That party really started the countrywide vogue of jazz music,” he wrote.21

Did that party actually happen? I haven’t found any articles about a party held specifically for Meighan, but he did attend a big bash at the Sherman Hotel on February 22, 1915, along with Travers—as well as Julian Eltinge, another entertainer Kingsley mentioned in his story.

And Essanay did in fact plan to film this party. (Whether that movie footage still exists anywhere is another mystery; most of the movies made by Essanay are lost.) My best guess is that Kingsley was writing about this party but got some of the facts wrong when he wrote his article four years later.

A group photo from the Reel Fellows Club party, published in Motography magazine.

It was the gala of a movie industry group called the Reel Fellows Club, and it attracted stars and executives from around the country, including Universal Pictures owner Carl Laemmle and Philadelphia mogul Siegmund Lubin, as well as a contingent of some 40 people from Chicago’s own Essanay.

Many of the guests danced until dawn. But the press coverage of this party—including a detailed story filling three and a half pages of Motography magazine—doesn’t say anything about Bert Kelly or a jazz band. “Music for the dancing was furnished by Benson’s orchestra of sixteen pieces,” Motography reported.22

Benson Orchestra of Chicago. Victor Records publicity photo, Bain News Service, Library of Congress.

This was probably an ensemble run by Edgar A. Benson, a St. Louis–born cellist and impresario who would start the popular Benson Orchestra of Chicago five years later, playing at Marigold Gardens in the early 1920s and featuring musicians such as drummer Gene Krupa. That group would make the earliest known recording of a jerky jazz rhythm known as stop-time, a 1921 song titled “Na-jo.”23 (Archeophone Records released a CD compilation of the Benson of Orchestra in 2003; several songs by the group are also on Spotify.)

But was Benson playing jazz—or something like it, a sort of proto-jazz—in 1915? And did Bert Kelly play at this gala? The Chicago-based magazine Motography did not use the word jazz when it described the music that night, but it did employ a nonsense word with a similar sound and energy when it offered this comment: “These all-night spasazams are fierce on us fellows who have to work for a living—especially the very next day at 8 a.m. Get that?”24

Brown’s Band and Frisco

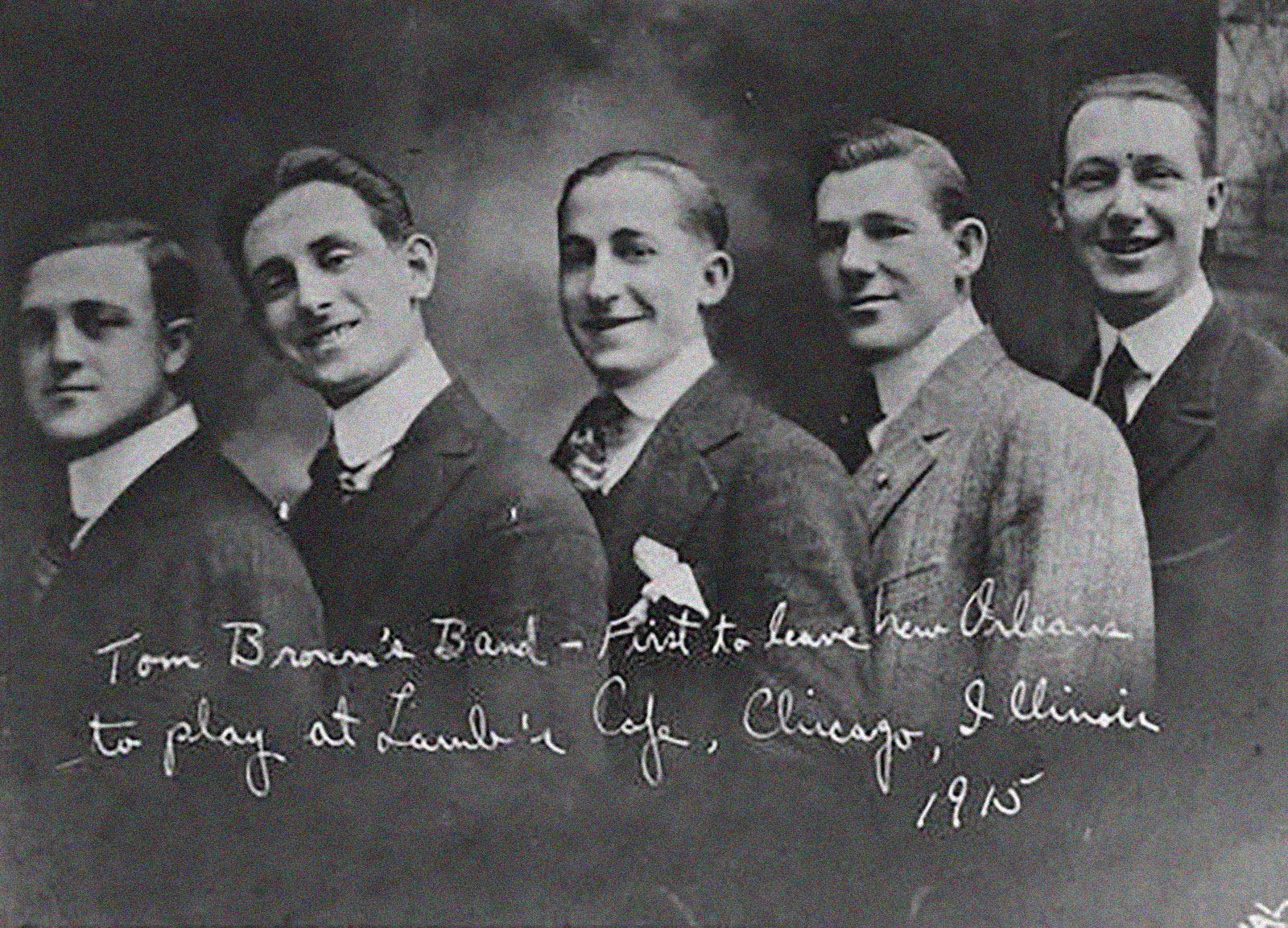

Chicagoans experienced more “spasazams” after a group of white musicians from New Orleans arrived at Chicago’s La Salle Street Station on May 13, 1915. Four days later, Brown’s Band From Dixieland—which was often known simply as Brown’s Band—started playing at a popular downtown cabaret restaurant called the Lambs’ Café.25 This might be the first band whose music was called jazz.

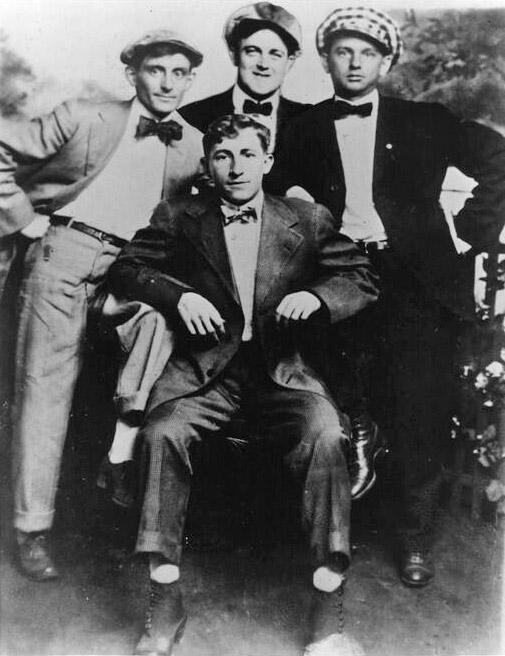

Brown’s Band, photographed in Chicago in 1915 soon after arriving for the engagement at the Lambs’ Café. Seated is Bill Lambert. Standing are Arnold Loyocano, Ray Lopez, and Gus Mueller. (For some reason, Tom Brown is missing from the photo.) Louisiana Digital Library.

Brown’s Band got the gig in Chicago with help from some influential people who’d heard them playing in New Orleans. One of these fans was the vaudeville dancer and comedian Joe Frisco, who was usually known simply as Frisco.

His real name was Louis Joseph or Josephs, and he wasn’t actually from San Francisco—he was born in Milan, Illinois, and grew up in Dubuque, Iowa.

He’d earned his nickname in Chicago, when he was a chorus boy in A Modern Eve26 at the Garrick Theater in 1912.27 He’d imitated the animated stepping of some showgirls from San Francisco, so the other chorus boys started calling him Frisco as an insult, but he embraced the moniker.

Frisco. Globe Photos Entertainment & Media.

Frisco, who used his stutter as part of his comic persona, wasn’t yet famous, but he soon would be. A 1925 profile in The New Yorker called him was “the comedian’s comic.”28 That same year, F. Scott Fitzgerald dropped his name in The Great Gatsby, describing a dancer “moving her hands like Frisco.”29

A decade earlier, Frisco had been impressed when Brown’s Band provided the music for a show he performed in New Orleans.30 The New Yorker described their encounter as the birth of jazz music, but the article made some questionable claims. Reporter Joe Swerling asserted that Frisco developed jazz dance as an art form before jazz music existed. Frisco’s jazz dance moves emerged out of his imitations of Charlie Chaplin, Swerling wrote:

He liked the way Chaplin wore his derby hat, the way he smoked his cigarette, the way he shuffled when he walked. Frisco dramatized Chaplin into a dance. He would cock his brown derby at a rakish angle, blow furiously on his cigar—which he always calls a heater—and shuffle along in a strange, unrhythmic rhythm. Lo, the jazz dance was born. …

Frisco had his jazz dance, but as yet there was no authentic jazz music. He found the essence of its technique in the strangely undisciplined antics of Brown’s Band. … Brown’s Band was forced to change its tempo to the irregular caperings of Frisco. Behold, jazz music was born.31

It’s true that Frisco performed a Charlie Chaplin dance. It’s likely he developed it sometime around the time when Chaplin came to Chicago to make movies at the Essanay studio in December 1914—and stayed for just one month. (See Chapter 9). But was Frisco doing his Chaplin routine in New Orleans? And did Frisco’s Chaplin dance influence Brown’s Band’s musical style? That’s uncertain.

When Ray Lopez, the band’s cornet player and manager, wrote about these events, he didn’t mention the Chaplin dance or any influence that Frisco had on his band’s music.32

Frisco encouraged Brown’s Band to take its music to Chicago, but the group didn’t immediately follow him north.33

In early 1915, Brown’s Band was doing “ballyhoo” work on the streets of New Orleans, using its music to advertise boxing matches.

Lopez recalled these days in letters to music historian Dick Holbrook, who published them in Storyville magazine in 1976. Lopez wrote:

… we were advertising fights on a big moving van from five till eight p.m. on the night of the fight. We’d stop at different corners in the heart of town and start playing. People would start dancing. I would pass out cards. That would go on for about three hours. Then we’d go to the club where the fights were being held and play between fights and get five dollars for the ballyhooing and fight, which wasn’t bad in those days.

One day, they were playing at the corner of Canal and Royal Streets, and they caught the attention of Johnny Swor and Charlie Mack, a pair of white vaudeville comedians who performed in blackface, calling themselves Two Black Crows. (Johnny was the brother of Bert Swor,34 was quoted in Chapter 11 about the definition of jazzbo.)

Mack shouted at the musicians: “Boys, y’all got steppin’ music, y’hear me? … What do you boys call this music?”

“We call it blues or ragtime. This is New Orleans music,” replied Tom “Red” Brown, the band’s trombonist and namesake. (At least, that’s what Lopez remembered him saying.)

“This music has got to travel, man!” Swor said. “How about coming north with us?” He told the musicians that they were heading soon to New York to perform in a big show called Maid in America. The band didn’t go north with the vaudeville duo, but Lopez handed his band’s card to Swor.

“Brown’s Band,” it said. “Music for all Occasions. Parades, Parties, Picnics and Balls.”35

Around the same time, showbiz producer Joseph K. Gorham saw Brown’s Band—also known as Brown’s Orchestra36—when he was walking along Canal Street in New Orleans. He’d never heard anything like this “discordant, yet strangely harmonious and amazing” music, according to the New Orleans Item.

“Mr. Gorham, observing the grinning facts, the snapping fingers, and the patting feet of the crowd that gathered around the wagon, was soon himself swaying to the barbaric tune,” the Item reported.

Gorham jotted down this note to himself: “Brown’s band, good rag orchestra, can’t read music, 1108 Camp Street.”

Arrival in Chicago

Gorham sent a message to Chicago, telling William “Smiley” Corbett, the owner of the Lambs’ Café, about these musicians he’d seen in New Orleans. (The café was on the same block as Gorham Theatrical Enterprise, which had an office in Room 1111 of the Schiller Building on Randolph Street.)

Corbett’s business partner, John Wilmes, replied with a telegram on March 17, 1915, asking: “are you sure Brown band right for our place answer me if you can have them come on What price wire me.”

Acting on behalf of the Lambs Café, Gorham signed Brown’s Band to a contract, taking no percentage for himself. (Recognizing his role in this deal, the New Orleans Item later called Gorham “Daddy of the Jazz.”)37

The five New Orleans musicians had a deal to play for six weeks starting on May 17, earning $105 a week. Wilmes paid for their tickets on the Illinois Central Railroad’s Panama Limited to Chicago.38

“We thought we had struck oil!” Lopez remembered. “The finest musicians who played the biggest theatres and hotels were getting 20 dollars and 25 dollars a week, and here we were, a bunch of ragtime lugs, getting as much as they were, plus a trip to Chicago! Man, we thought we were two blocks this side of the Pearly Gates and St. Peter was beckoning us to come on in!”39

But these young fellows from New Orleans were in for a rude welcome in Chicago. Lopez wrote:

We felt scared, sober and alone. When we hit Chicago we went directly to the Commercial Hotel at Wabash and Harrison. It was a dump! The “el” made a turn right past our window. The manager threatened to throw us out unless we stopped wood-shedding.

We put on our pongee suits and straw hats and headed for Lambs Cafe. Lordy, it was cold. The damnyankee air cut through our thin suits. We had 30 dollars between us, bought caps at Marshall Field’s. We asked for dark colors. The salesman thought we said “dog collars.” They were 35 cents each.

Everything was rush, rush, rush. We were numb from the cold.

At the Lambs’ Café, they met Corbett. Lopez described him as “big, fat and happy.” But he didn’t stay happy when he heard Brown’s Band playing.

“Where’s your sheet music?” he asked.

“In our heads,” they replied.

To demonstrate their chops, Brown, Lopez and their bandmates—clarinetist Gus Mueller, drummer Bill Lambert, and pianist Edward “Mose” Ferrer, who was filling in temporarily for Arnold “Deacon” Loyocano—played “The Memphis Blues,” a W.C. Handy song published in 1912. Lopez recalled Corbett’s reaction:

We kicked off, and twisted that number every way but loose. We worked it up to the pitch that used to kill the folks back home—and found our way back as smooth as glass. We were right in there. It sounded fine. But Corbett was white as a ghost. He roared: “What kind of noise is that! You guys crazy—or drunk?”

According to Lopez, the band then tried to win over Corbett by playing a novelty tune, with the musicians imitating the noises of barnyard animals. “The cashier made faces and held her ears,” Lopez said.40

This song, known as “Livery Stable Blues,” later became the subject of a federal lawsuit over who exactly wrote it, and it’s questionable whether Brown’s Band actually played it at this time in 1915. Frisco, who was performing at the Lambs’ Café, testified that he never heard the band play the song there.41

After hearing these samples of Brown’s Band’s music, Corbett said: “OK, men. You open tomorrow night. How do you want to be billed on the sign out front?” The group asked to be billed as Brown’s Band From Dixieland, but Corbett didn’t bother putting any name on his club’s sign. All it said was: “Dancing Here.”42

The café’s May 15 advertisement in the Chicago Examiner’s “Where to Eat” column had been similarly vague: “PUBLIC DANCING,” it said, offering one other incentive: “Souvenir Prizes.”43

“The Lamb’s Café engagement started out dismally,” Richard M. Sudhalter wrote in his 1999 book Lost Chords: White Musicians and Their Contributions to Jazz, 1915–1945. “The expected crowds didn’t materialize.”44 (Chapter 1 of Lost Chords, which covers these events, is available to read at the New York Times’ website.)

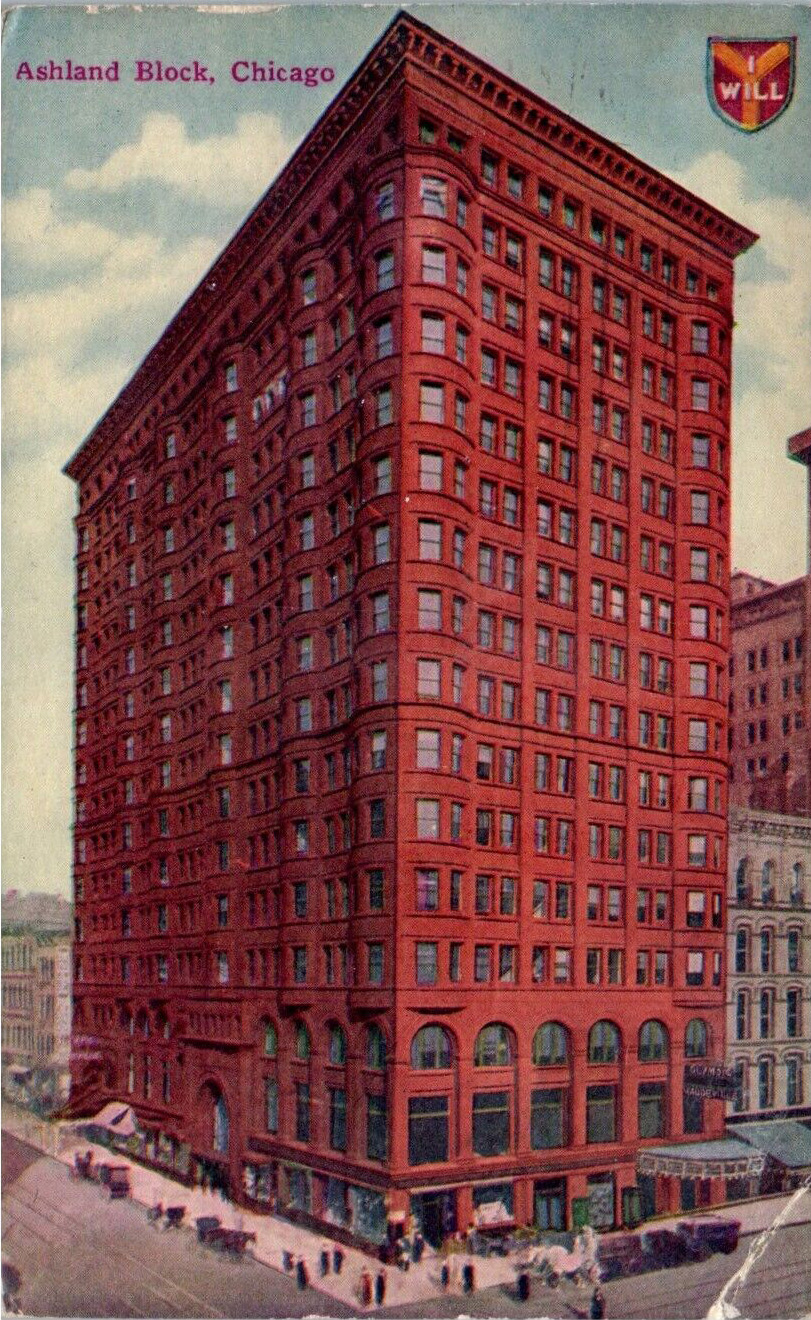

The Ashland Block. eBay.

The Lambs’ Café

The Lambs’ Café was in the heart of Chicago’s Randolph Street theatrical district. It was located in the basement of the Ashland Block building at the northeast corner of Clark and Randolph.45

Journalist and drama critic Charles Collins called this intersection “Chicago’s grubby Place De L’Opera,” likening it to a famous square in Paris. “Stand here long enough, and the man or woman you have been hunting for years will pass by. It is one of the cross-roads of the world for those that follow the mirage of the night-life.”46

The Lambs’ Café had been listed at different addresses over the previous few years—70, 87, and 78 West Randolph—all of them near that intersection.47 The name was spelled Lambs, Lamb’s, or Lambs’ in various articles, ads, and directories—with or without the. (I’m using the Lambs’ spelling because that’s how it appeared in 1915 newspaper ads.)

It was downstairs from the Ashland Drug Store, “where through every hour of the night chorus girls load themselves down with cosmetics, if their accompanying Johns are generous, and where night-workers wait for northbound trolley cars,” Collins wrote.

The Schiller Building, later known as the Garrick Theater, circa 1900. Wikimedia.

The entrance for the Olympic Theater was in the same building, although the theater itself was in an adjacent structure. The Garrick Theater—in the Schiller Building, designed by Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler—was just east of that. (Decades later, Richard Nickel famously led a fight to preserve the Garrick Theater, but the magnificent building was demolished.)

The Sherman Hotel

The Sherman Hotel was across the street from the Lambs’ Café, to the west. The hotel included the College Inn, which Collins called “the red-letter rendezvous of the town’s upper Bohemia.”48

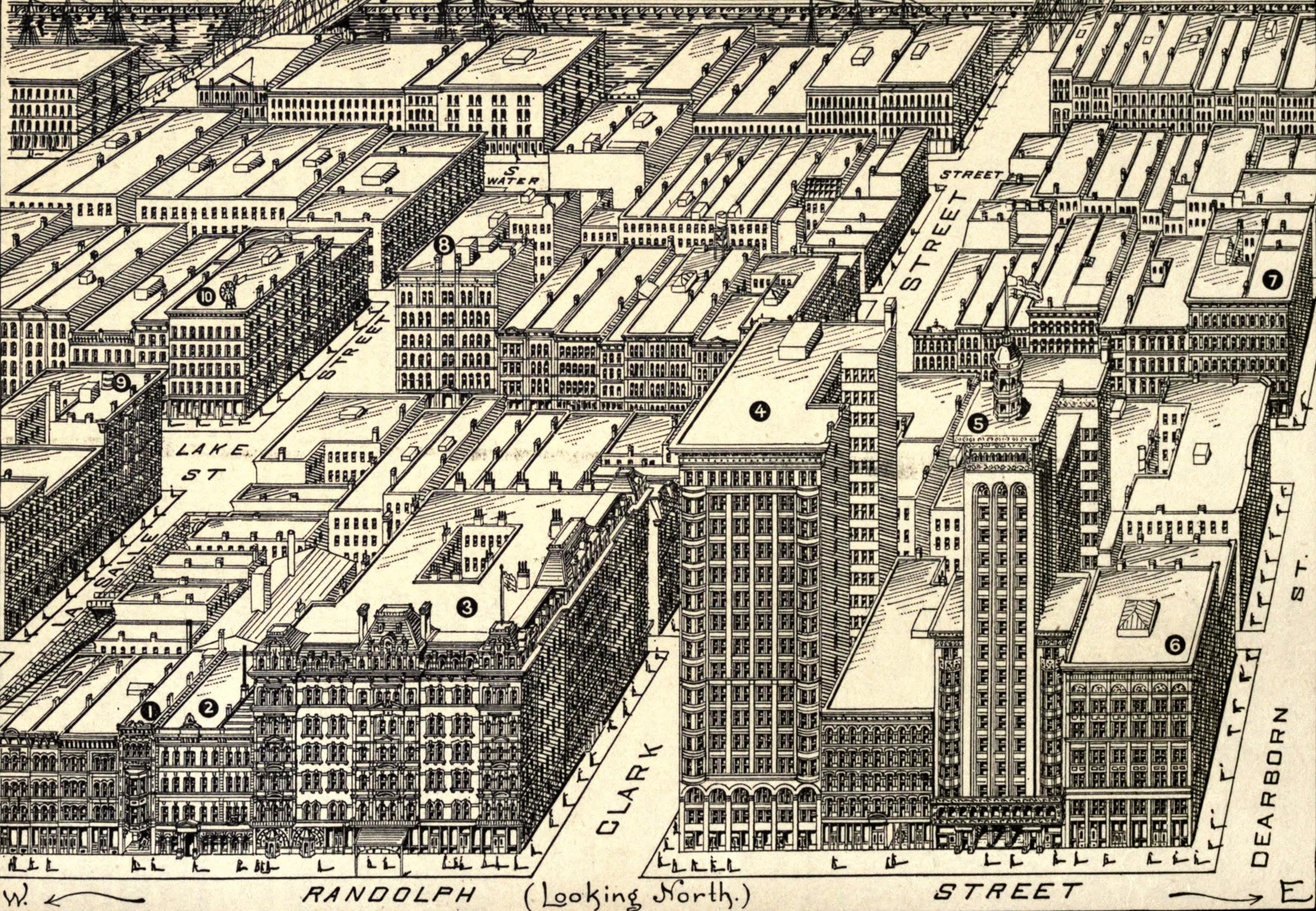

This illustration from Rand, McNally & Co.’s Bird’s-Eye Views and Guide to Chicago shows the Ashland Block—labeled with number 4, it’s the tallest building in the picture—and the surrounding blocks as they appeared in 1893. Many of the other buildings were still there in 1915. The other numbered buildings are: 1. Hooley’s Theater, renamed Powers’ Theater in 1898. 2. Fidelity Building. 3. Sherman House, which was replaced by a new Sherman Hotel building in 1911. 5. Schiller Theater Building, known as the Garrick Theater after 1903. 6. Borden Block. The Olympia Theatre was in the building between the Ashland Block and the Garrick Theater.49

The Lambs’ Café was named after the Lambs, New York City’s famous social club for theatrical folk.50 And that club was named after siblings Charles and Mary Lamb, who’d hosted actors and literati at their London salon in the early 19th century.51 True to its name, Chicago’s version of the Lambs was a popular hangout for actors and other people who worked in theaters.

“After the College Inn closed for the night, you could usually find comfort and friends who would sit up until dawn in the Lambs,” a Tribune writer recalled in 1939.52 Collins remembered the Lambs’ Café as “a clubby resort, where players, paragraphers and politicians meet each other or their mistresses.”

He continued: “Here are many familiar faces—among them young Jack Barrymore … and [Tribune theater critic] Percy Hammond, the fat boy of the sneering polysyllables. They are bitterly cursing their respective professions as they devour T-bone steaks smothered with onions.”53 In addition to those steaks, the restaurant was famous for its “rolling mill style” corned beef and cabbage.54

Lopez said the cabaret’s name had another, creepier connotation. “It was first-class cafe, a sort of a hide-away for a lot of old judges, lawyers, high police officials, who would meet their little girl friends, who were known as ‘lambs’ about to be shorn of their virtue,” he wrote. “… We catered to the theatrical crowd, with a few of the elite who were out on the town, so to speak.”55

Smiley Corbett always seemed to be there,56 greeting patrons with his trademark grin.57 He was “an unctuous host, seeming to hold all the strings of nocturnal intrigue in his pudgy hands,” Collins wrote.58

Corbett had grown up in Smoky Hollow and Little Hell, poor Irish neighborhoods on Chicago’s Near North Side. He’d worked as a railroad brakeman, a deputy coroner, and the agent for Lemp Brewery.

He became well known as a member of a group called the Dugans, who were always carousing at Malachi Hogan’s saloon.

The cohort also included John Butterly, a bartender who later had a saloon next to Green Mill Gardens. (See Chapter 8.) Like Butterly, Corbett had moved north, residing in the neighborhood that became known later as Uptown; his home was at 4739 North Sheridan Road59 (a block away from Gordon Seagrove, the Tribune reporter who wrote the first story about jazz music as recounted in Chapter 11).

Smiley’s brother John Corbett was one of the developers making plans to build the Edgewater Beach Hotel, the iconic resort that would open in 1916 on the lakefront less than a mile north of Smiley’s home.60

The City Hall Square Hotel, in 1914. eBay.

In addition to the Lambs’ Café, Smiley was president of the Ashland Catering Company61 and the half-owner and manager of the City Hall Square Hotel, which was just across the street from Lambs’, on the south side of Randolph.62

“Strange birds roost there,” Collins said about the hotel, where Smiley often went at the end of the night. “The guests are troubled in their daytime slumbers by the tin-pan-alley effects in the music publishers’ offices, next door.”63

The Tribune called Smiley “perhaps the best known of all the loop hounds,” using a term for downtown’s nightlife crowd. Author Edna Ferber explained: “The Loop is a clamorous, smoke-infested district embraced by the iron arms of the elevated tracks. … And he who frequents it by night in search of amusement and cheer is known, vulgarly, as a Loop-hound.”64

Corbett and another member of his gang, Tom Hanton, entertained crowds by singing rousing tunes: “When Hogan Paid His Rent,” “There’ll Be Murder Here Tonight” (with the word sometimes spelled “Murdher,” to suggest an Irish accent), “The Wind That Shakes the Barley,” and “one which was known as the ‘Lamentation.’”

They also told jokes. “They were a couple of rough ‘Turks,’ but very original and entertaining as companions in any company,” recalled Charles H. Hermann, who ran downtown’s Chapin & Gore Distillery. “Both could create laughs with their Irish songs … ‘Smiley’ was sharp as a tack at repartee.”65

Corbett often attended theatrical shows and horse races, and he was a prizefighting maven. (He seems like a kindred spirit of another Irish American saloonkeeper in Chicago who loved boxing, Charles E. “Pop” Morse, founder of the roadhouse that became Green Mill Gardens. See Chapter 1.)

People placed hundreds of dollars in bets at Corbett’s café when a ballyhooed boxing match was coming up.66 When Jack Johnson, the Black heavyweight champion, was set to fight white pugilist Frank Moran in Paris in 1914, the Tribune asked Corbett for his prediction. “Moran has a Chinaman’s chance to win,” he said. “In fact, he has about as much of a chance as I have, and I am right here in Chicago. I think the Negro can whip three Morans in the same ring.”67 Johnson did, in fact, win.68

On another occasion, Essanay cinematographer Conrad Luperti sued Corbett and his business, alleging that Lambs’ Café employees had wrecked his movie camera when he tried to film New Year’s festivities in the place. “We treated him gently, but would not let him operate here,” Corbett said. “Some man and his wife were quarreling a little and the motion picture operator attempted to expose the film to get the scene. We wouldn’t stand for it.”69

On the same day when Brown’s Band began playing at the Lambs’ Café, the owners were ordered in court to pay $1,200 to a former waiter, Charles Oxner, who’d been beaten up during a 1913 “wine party” at the restaurant.70

Cheering for “Dixie”

In spite of such incidents, the vibe at Lambs’ Café could be classy or even tranquil. In January 1914, Charles J. McGuirk described a visit: “the sounds of the orchestra rose every little while over the clink of glasses and coin. On a small stage, flanked by vines or artificial trellis, three dancers, two women and a man, whirled in an artistic creation. … It was pretty, and the audiences applauded wildly.”

McGuirk, who was writing for the Tribune, took a job later that year at Essanay, where he worked and drank alongside Charlie Chaplin. (See Chapter 9.) When McGuirk visited the Lambs’ Café, he was investigating why so many Chicagoans applauded enthusiastically whenever they heard Daniel Decatur Emmett’s famous 1859 song “Dixie,” despite the tune’s strong associations with the South.

McGuirk’s article didn’t examine whether the song’s popularity had racial overtones. This was in the early years of the Great Migration, when many African Americans were moving from the South to Chicago and other cities in the North. It was also a time when many white Southerners were making a push to portray the Confederacy as a heroic cause. McGuirk didn’t address any of that, but he did wonder if the folks who cheered “Dixie” were migrants or visitors from the South.

Asked about enthusiastic responses to “Dixie,” Corbett told McGuirk: “I’ve noticed it myself. They always go up in the air when ‘Dixie’ is played, and they’ll sit quiet for ‘The Star-Spangled Banner.’ But you’re wrong about them being from the South. Why, some of the wildest have been born in the Fifty-Four-Forty section of the United States. What’s the reason? You got me. I’d like to know myself. Wait a couple of more dances and I’ll have them play ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ and ‘Dixie,’ one right after the other, to show you what I mean.”

Corbett ordered the band to play the two songs. “And it came about just as ‘Smiley’ had prophesied,” McGuirk reported. “There was polite handclapping for the first which rose into a riot at the second.”

McGuirk asked some of the Lambs’ Café patrons why they’d cheered so vigorously when they heard “Dixie.” One man remarked: “I guess it’s a habit. Always done it. Thought it was the right thing to do. Why? Have they passed an ordinance against it? They’re closing this town so tight you’ll soon have to get a permit signed by the city council to buy a pair of rubber heels.”

“I suppose I have the habit, too,” a woman told McGuirk. “You don’t have to be from the South to say ‘hello’ to something you like, do you?”

Another man had this to say about the song: “In the first place, you got to hand it to it. It carries the goods. After the first two or three bars get across you know they mean something. That tune shouts its own history every time it is played. Another thing. My daddy fought in the Civil War. He was with Grant and McClellan and the Army of the Potomac. Now I have an imagination. When they play that tune and I get that ‘we’re goin’ to win if we die for it’ spirit, I imagine I can hear the ‘rebel yell’ over the guns. And I get an awful lot of respect for my father for even stoppin’ to reload, let alone stickin’ out the fight.”71

A little more than a year after this article appeared, the Lambs’ Café featured a band with Dixieland in its name. In Lost Chords, Sudhalter offered this explanation for why this word was added to the name of Brown’s Band:

By that time, the terms “Dixie” and “Dixieland” had long been understood as synonyms for the South. Whether taking its origins from the Mason-Dixon Line or, as various scholars have maintained, from a French-derived slang name for an old Louisiana ten-dollar bill, “Dixie” was in use well before the Civil War. The idea of “Dixieland,” especially antebellum, as a lyrical paradise was central to the songs of Stephen Collins Foster, a key feature of late nineteenth-century minstrelsy, and persisted as a current in early twentieth-century popular songs. In wide public consciousness it was long a way of identifying things southern, related to a mythical Elysium—and it included various kinds of characteristic music.72

Unlike many of the other musicians from New Orleans who’d played in Chicago, the men in Brown’s Band were white—making it possible for them to perform in venues with white owners and white audiences where Black artists rarely if ever performed. (One might call Lopez a Latino or Hispanic, but he identified himself as Caucasian; his father was an immigrant from Spain. 73) Lopez made this comment about the racial dynamic among New Orleans musicians at that time:

I never did play with any Negro bands, but did know King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Freddie Keppard. Personally, I would say Freddie Keppard was the hottest, Manual Perez was the sweetest. Negro and white musicians didn’t play together in a band, but there was no place in New Orleans where a white band could play that a Negro band could not: no blacks and whites, just good and bad musicians. There was one major difference: the Negro musicians sometimes sang. Our music wasn’t loud. It was very simple. The cornetist played the lead. We all cut it together. It was happy hearts, friends-together music.74

The entertainment scene

As Brown’s Band began its gig at the Lambs’ Café, the group sometimes accompanied Frisco, the dancer they’d met in New Orleans.

“I was doing an act called a ‘Charlie Chaplin Imitation,’” Frisco later testified, saying he performed at Lambs’ from April through late August 1915. If he was correct about those dates, that means he was there before Brown’s Band arrived and then he continued performing throughout their run at the venue.75

Nearby, McVicker’s Theater at Madison and Dearborn was advertising a mysterious show with the tagline: “Is he Charlie Chaplin? (Not a Motion Picture) Come and Scream.”

At the Majestic—a theater at 18 West Monroe Street, known today as CIBC Theatre—the “supreme vaudeville” show featured an up-and-coming act billed as Four Marx Brothers & Co.76 (At the time, the Marx family lived in a greystone at 4512 South Grand Boulevard, now called King Drive.77)

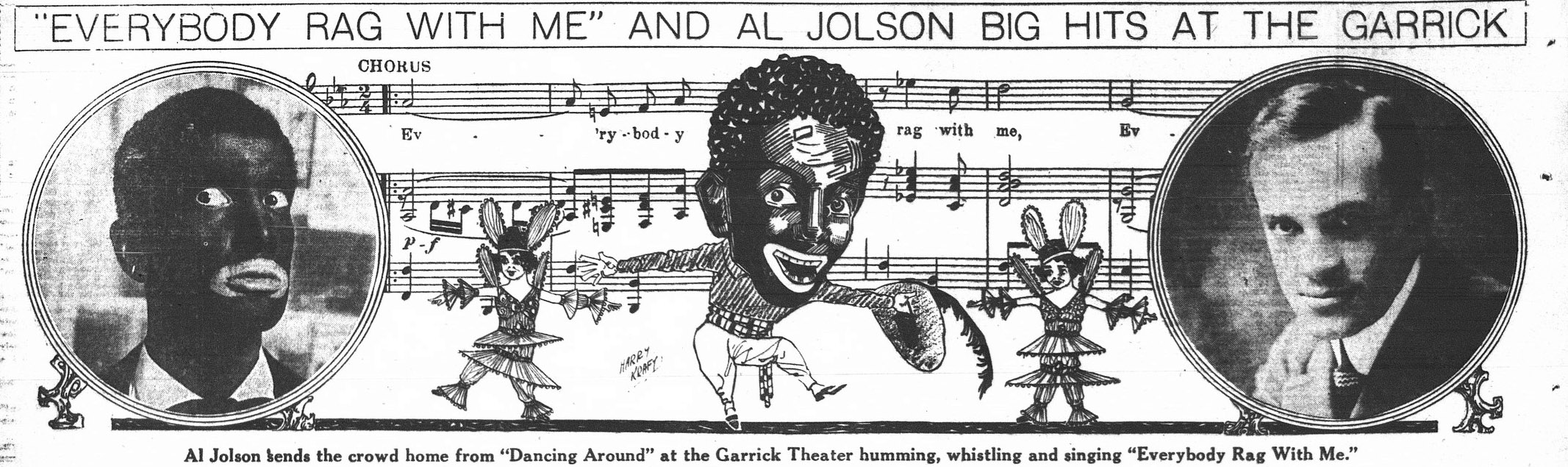

Meanwhile, Al Jolson was starring in Dancing Around at the Garrick, half a block east of the Lamb’s Café. Before the show’s finale, he would ask the audience, “Shall I sing ‘Everybody Rag With Me’ in white face or black face?”

Chicago American, May 19, 1915.

“Vociferous cries of ‘White face’ almost always decide the question, and, just before the finish of the entertainment, Jolson dashes on with his features as Dame Nature intended he should look,” the Chicago American reported.

Some audience members didn’t recognize Jolson without the black makeup that usually covered his face.

“I want to dance, dance, dance, dance, dance, till I drop, I don’t ever want to stop this ragging,” he sang.78

Chicago American, May 20, 1915.

That tune was the big hit of the moment, and many big-name singers were performing their own versions, including Sophie Tucker, Blossom Seeley, and Isabella Patricola,79 who was scheduled to headline Green Mill Gardens when its summer gardens opened for the season on May 28.80 (For more about Patricola, see Chapter 10.)

“Our debut was pitiful”

When Brown’s Band made its Lambs’ Café debut, the cabaret had been decorated to resemble a farm. Corbett (or someone in the management) apparently thought this was the type of scenery that the music would evoke. Lopez wrote:

Inside the cafe it was dressed up like a barnyard—paper pumpkins and hay on the floor, a stuffed rooster on the piano. Yellow moon overhead blinked on and off. The band wore straw farmer-hats and polka-dot ties. We were told this was a perfect setting for our kind of music. Brown finally quieted us down.

Well, our debut was pitiful. Those Yankees wouldn’t listen or dance. They just walked out on us. We took turns talking to the customers. “Folks, this is New Orleans music. Hot music. People down South dance. You’ve got to dance. Come on and try. Have fun.”

For six nights we pleaded. No dice. Our blues were the most beautiful we had ever played, but Corbett said: “Now what are you playing? That’s dirtier than the other stuff. Go back to Dixieland!”81

The café’s management sent a telegram to Gorham, complaining about the situation. Gorham recalled:

The boys had been there hardly a week before I got a wire from the management of Lambs asking me to take them off their hands. It explained that their music was too noisy and wasn’t taking at all. I wired back, as Lamb’s is rather a small place, for them to tone down a little and try again. Lopez wrote me, much discouraged over his first efforts. All of his boys were nice young fellows, who never before had been away from New Orleans. I wrote him in reply just to ease up a bit and keep going.82

The performances hit a low point around this time, according to Lopez:

Our eighth night was the worst. The star was Drigo, a gypsy violinist. We had to accompany him. We phrased our part our own way. This threw him off. He put down his fiddle, shook like he had the palsy, and said: “Meester Brown, do you call yourself a musician?”

Brown said: “Mistuh Drigo, ah am a musician, but your kind of music just ain’t on my trombone.” Drigo stomped out. The waiters and chef hollered: “Strike!”

We played on. Mose Ferrer yelled: “It’s a war of nerves, men! Louder!”

The colored busboy hollered: “Blow ’em out, white boys!” He was fired. We fastened our contract to the moon and played on.

Brown’s Band got a boost from Johnny Swor and Charlie Mack, those blackface performers who’d seen them playing in New Orleans. Swor and Mack were in Chicago now, performing in Maid in America, which opened June 1 at the Palace Music Hall, at 127 North Clark—across the street from Lambs’ Café.83

When Lopez told Swor that his band was “a big flop” in Chicago, Swor replied: “All you need is somebody to break the ice. That’s the way it goes in this business. Your music is new to them. Different. Tell you what. Go tell Smiley Corbett to reserve the whole room for the Maid in America company tomorrow night. We’ll bring the whole cast over.”

The following night, 75 Maid in America cast members filled the Lambs’ Café at 11:15 p.m. Lopez recalled:

We exploded into music and played till about 6 a.m. They danced the varnish off the floor. And Corbett was happy! … The night after Swor and Mack brought the show folks to Lambs Cafe our music caught on like magic. Word went around that a hot band was at Lambs, and folks lined up to get in. They added a cover charge of ten cents!84

Brown’s Band, photographed in Chicago in 1915 with Frisco. Louisiana Digital Library.

“Jazz it up, Ray!”

Although Brown’s Band was billed as a ragtime group, it’s clear that something sounded different from the style of music these New Orleanians were playing. It wasn’t the same sort of ragtime that Chicagoans were accustomed to hearing.

Frisco later testified that his Chaplin routine at the Lambs’ Café was “what they call a jass dance.” He also said that Brown’s Band had played “so-called jass music.” However, it’s not clear if Frisco meant that people in 1915 had actually used the word jass. When he testified about this in 1917, was he just using the vocabulary of 1917?85

Joseph Gorham, the producer who’d signed Brown’s Band, said that the word jazz, “common to knowledge and frequent in the vocabulary of the Barbary coast and the southern darky for years, means simply enough, and without any explanation or definition, the only thing it’s possible for four such letters in such order, when pronounced, to convey—and that is just ‘to mess ’em up and slap it on thick,’” the New Orleans Item reported in 1919.86

According to various stories, people did use the word jazz in 1915 to describe the music Brown’s Band was playing, although there’s scant printed evidence of it. “A string orchestra (which included a young French-born pianist named Jean Goldkette…) quit in protest at the new band’s raucous sounds, hurling at it the pejorative word ‘jazz,’” Sudhalter wrote. 87

Tom Brown later said the Chicago musicians’ union was angry about these nonunion players performing at Lambs. And so, the union tried to smear their reputation by spreading the word that they were playing “jazz music.” According to Brown, the union used jazz as an insult because it was a vulgar slang word common in the Levee, Chicago’s prostitution district.88 By calling it “jazz music,” were they essentially saying it was “fuck music,” “fucking music,” or words to that effect?

This story raises an interesting possibility: Did Brown’s Band remind those union musicians of tunes they’d heard in Chicago’s brothels and other red-light district joints? And was jazz just a slang word for sex—or was this sort of music already being called jazz in the Levee? I’m not aware of any evidence to prove this hypothesis, but it seems at least possible. For years, African American musicians had been performing ragtime in the Levee’s brothels and bars.89 It’s conceivable that some of them may have reshaped ragtime into something more like jazz, but there’s no written evidence so far that anyone was calling their music jazz.

Lopez, however, cast doubt on this story about union musicians using jazz as a slur against Brown’s Band. “I never heard of any beef to the union that we were non-union, or ever saw any knock in the paper saying that the music at Lambs was ‘jazz music,’” he wrote.90

Lopez told his own version of how the word jazz came to be associated with Brown’s Band, crediting the boxing manager and announcer John J. “Darby” Kelly.91 According to Lopez, Kelly called out “Jazz it up, Ray!” at a show by Brown’s Band, using the same expression Lopez had heard William Demarest say a few years earlier in New Orleans. Here’s how Lopez told the story:

Darby Kelly was a little character who used to hang around the Loop. He was a grifter from the South Side, a natty dresser; always wore silk shirts and a Panama hat. “Darby” was slang of that time for gags and jokes. Darby liked to dance. … He particularly liked to show off on a dance-floor. He also had a buddy named Low and Squatty Joey Sherman, an ex-fighter.

Well, one night during our third week, we had just finished playing a beautiful number called “Hawaiian Butterfly” when Darby Kelly shouts: “Jazz it up, Ray!” We jumped into a tune called “Banana Peel Rag (Some Slippery Number).” That turned the crowd into a bunch of whirling dervishes. Everybody got high—threw themselves into wild abandon—even folks sitting at the tables who couldn’t make the 30-by-30 dance floor.92

Lopez was under the impression that Kelly was connected to the South Side mob.93 At various times, the Tribune called Kelly “the noisy announcer,”94 “the silver tongued announcer,”95 and “a noted al fresco orator, who yodels the names and weights of the fighters in the rings around Chicago.”96 He often traveled around the country for his work in boxing, including visits to San Francisco97 and New Orleans, two of the cities with claims on the origin of jazz.

In 1914, another boxing manager, Ralph “Fleck” Collins, told the Inter Ocean that Kelly was working as a waiter in New Orleans—or as the newspaper put it: “Darby Kelly has got a job in New Orleans dealing off the arm in a two-bit table d’hote eat shop.” This may have been a joke of some sort. “They have only one course, and they serve that in a big bowl with a tin spoon,” Fleck remarked.98 Darby was back in Chicago by 1915, when he teamed up with Fleck99 to open an athletic club and gymnasium at 55th Street and Grand Boulevard on the South Side, where Darby was the boss.100

After Darby Kelly shouted “Jazz it up, Ray!” and sparked a frenzy on the dance floor, Smiley Corbett called over Lopez and introduced him to “two big wheels” with Lyon & Healy.101

Founded in Chicago in 1864, Lyon & Healy was the world’s largest music house in the early 20th century, selling a huge variety and volume of sheet music, along with “talking machines and records,” pianos, organs, violins, brass instruments, and the company’s own line of harps.102 In 1915, Lyon & Healy had a store at 202 South Wabash Avenue, near Adams Street, in a section of the Loop known as Music Row. That was several blocks from the Lambs Café.103 (Lyon & Healy moved to a new store at the northeast corner of Jackson and Wabash in May 1916.)104

Lopez recalled talking with the two men from Lyon & Healy:

They asked me what style of music we were playing. I told them it was ragtime. They asked if there was any other name for it as they had heard Darby Kelly shout “Jazz it up, Ray!” After a few minutes of talk, I went back to the bandstand. Smiley, in the meantime, sent a waiter over to his hotel across the street [the City Hall Square] and got a big dictionary. The three started looking for the word jazz. The nearest thing they could find was jade, a “wild and vicious woman.” They seemed very much interested in the word jazz.

A couple of nights later I saw Darby and asked him what kind of music he called our music. He said: “Jazz.” I asked why. He said it made you want to jazz—made you want to get laid. He said it was an expression used on the South Side in the better circles amongst the whores and pimps. That’s why we couldn’t find it in that old dictionary. 105

Ad campaign

Curiously, it appears that Corbett or someone associated with Lambs’ may have tried using the word jazz to promote Brown’s Band. On May 22, 1915, an ad appeared in the Chicago Examiner for the café, announcing “THE ORIGINAL JAD ORCHESTRA FOR DANCING.”

That could have been a typo for jazz or jaz. It’s easy to imagine a typesetter looking at the letters JAZ and assuming it must be a misspelling. Or perhaps someone dictated the ad copy, saying, “J-A-Z,” and the listener misheard that Z, thinking it was a D.106

But this advertisement appeared only seven days after Brown’s Band started playing at the Lambs’ Café, and that doesn’t match up with Lopez’s chronology. The way he told his story, the incident when Darby Kelly shouted “Jazz it up, Ray!” seemed to happen later. And yet, it’s hard not to wonder: Did the ad’s “JAD” spelling result from Corbett’s efforts to find jazz in the dictionary? It’s possible Lopez misremembered some of the details about exactly when all of these events took place.

I searched other Chicago newspapers, including ones that haven’t been digitized, for similar ads about “jad” or jazz music at the Lambs’ Café. I didn’t find any other ads published on May 22, 1915, but it’s possible those newspapers may contain some references to Brown’s Band that haven’t yet been discovered.

The New Yorker’s 1925 profile of Frisco includes another anecdote about the word jazz emerging at the Lambs’ Café in 1915. According to the story, Frisco’s fans included Chicago racecar driver Art Greiner,107 who prepared a piece of parchment with elegant script declaring: “We, the undersigned, do hereby recognize Frisco to be the greatest jazz dancer in the world.” The New Yorker reported that this document “was signed by a long and illustrious list of names and presented to Frisco with much ceremony.”108

As Brown’s Band started attracting crowds, its name finally appeared on the café’s sign. “The band’s name was never in lights, just a little sign about three feet square on both sides of the marquee saying ‘Brown’s Band from Dixieland—Dancing,’” Lopez recalled. “Brown’s Band was never billed as a jazz band, not as long as I was with the outfit.”109

On May 26, the Chicago Examiner used the group’s name in an ad for the first time, announcing: “BROWN’S BAND direct from New Orleans, playing dance music at the Lambs’ Cafe from 4 to 6 and 8:30 to 1 o’clock.” It also noted: “Concert music from 6 to 8:30.” That seemed to refer to another ensemble, performing music that wasn’t quite so rowdy.110

Starting on June 2 and continuing through June 19, the Lambs’ ads in the Examiner promised “Special Ragtime Dinner Music” by a group called:

BROWN’S BAND

From Dixie Land

In mid-June, the ads also mentioned performances by another group, the Original Jug Band. The ads stopped running after that, even though Brown’s Band continued playing.111

“A weird strain” of music

According to Lopez, Bert Kelly’s band was playing during this same stretch of time at the College Inn. “Bert Kelly was a very fine fellow and a damn good friend of mine,” Lopez said. “… When Brown’s Band was playing at the Lambs Cafe, Bert had a four-piece band playing at the College Inn room of the Sherman Hotel, right across the street from us.”

But Lopez didn’t back up Kelly’s story claiming that he’d used jazz band as part of his group’s name. “I never heard them called any name but Kelly’s Band,” Lopez said. “Bert played beautiful banjo. His type of music was sweet—wouldn’t set your bowels in an uproar—mostly show tunes, very melodic. The main attraction at the College Inn was the ice-skating show … and the cuisine. They served marvelous food.”112

Decades later, Kelly seemed to resent New Orleans musicians for getting all the credit for inventing jazz. Kelly wrote a letter to Variety in 1957, saying that he wanted “to unravel the skein of ridiculous falsehoods concocted by over-anxious writers, publishers and music critics who start with the erroneous premise that the jazz-band and jazz style of dance music were originated in New Orleans and the etymology of the word jazz could be found in New Orleans or Africa instead of in the ’49ers mining-camp dancehalls of the Far West.”

Kelly said that Brown’s group was the first “Dixieland band” to play in Chicago (erroneously saying it was in 1916 rather than 1915). But he added: “They did not play jazz rhythm nor claim it; in fact Tom and his musicians told me they had never heard the word jazz in New Orleans.”113

However, this contradicts what Kelly had said when he gave a deposition in the 1917 copyright lawsuit. At that time, Kelly testified that “Brown’s Original Jass Band from Dixie was the first jass band to his knowledge.” Curiously, Kelly included “Jass” as part of the band’s name when he gave that testimony.114

In a different “sworn statement,” which was printed in 1919 in the New York Sun and New Orleans Item, Kelly said: “The phrase ‘jazz band” was first used by Bert Kelly in Chicago in the fall of 1915 and was unknown in New Orleans.” Note how Kelly (referring to himself in the third person) said he’d coined the phrase in 1915, rather than 1914, as he would later claim. In this statement, Kelly once again made an error about the year when Brown’s Band played at the Lambs’ Café, saying it was in 1916, when it was actually 1915.

Kelly’s statement parenthetically noted: “Note they did not use the ‘jazz band.’” But Kelly did have this to say about Brown’s Band: “This was the first and by far that best band that ever came from New Orleans.”115

If we give Bert Kelly the benefit of a doubt—if we accept his story that he’d used the phrase jazz band in 1914 or 1915—that creates an interesting scenario. Kelly was playing across the street from Brown’s Band in 1915, when he befriended Ray Lopez. Kelly saw Brown’s Band performing, and Lopez saw Kelly’s band. Both men said they’d heard the word jazz before coming to Chicago—Kelly in San Francisco and Lopez in New Orleans.

Did Lopez hear Kelly using the word, or vice versa? What if they both brought this lingo to Chicago? What if those union musicians and boxing announcer Darby Kelly also carried this slang to this prominent crossroads of Chicago’s theatrical district, after hearing it in the South Side’s Levee? It may be impossible to know who spoke the word first around the corner of Clark and Randolph, but it’s not hard to imagine this buzzword circulating in the crowds of Loop hounds who gathered at this hot spot in the summer of 1915.

Lopez once said that he and his bandmates “tried to support each other and produce something melodic and rhythmical, instead of trying to drown each other out and make a lot of noise. Someone would come up with an improvised passage and they would work it into a sort of harmonious counterpoint behind the lead, who would be improvising off the melody.”116

“Lopez was the cornetist who first muted his instrument with a derby hat, and Tom Brown used the same idea on his trombone,” Joseph Gorham said.117

The New Yorker reported that Brown’s Band learned this move from Frisco, the dancer: “One day they played too fortissimo to suit the dancer’s fancy. He took off his brown derby and hung it over the tenor saxophone. Every jazz band windjammer to-day hangs a derby hat over his instrument, in certain ecstatic moments of the number, and doesn’t know why. But Frisco knows.”118

Brown’s Band, photographed in Chicago in 1915. The photo includes Larry Shields, who replaced Gus Mueller on clarinet that August. Louisiana Digital Library.

Brown’s Band played an original composition with the intriguing title “More Power Blues,” which Lopez said he’d written around 1912. During the plagiarism lawsuit, Lopez asserted that the Original Dixieland Jass Band’s 1917 record “Livery Stable Blues” was the same tune as “More Power Blues”—except that it had additional farm animal noises. (I will write more about the lawsuit in future chapters.) When Lopez testified at the federal courthouse in Chicago, he had trouble articulating what was so distinctive about “More Power Blues.” Nevertheless, his testimony offers some hints at what Brown’s Band sounded like.

Q. What was the nature of that composition?

A. Well, it was a rag time composition with an interlude played rather in an odd way.

Q. Describe it as near as you can compared with other compositions?

A. It was a little different from other numbers.

Q. Can you state—can you give a more accurate description as to melody?

A. It had a strange strain of melody that was a little different from any other melody. …

Q. What do you mean by rag time?

A. Syncopated.

Q. Syncopated time?

A. Yes, sir. …

Q. You said it had an interlude played in an odd way, what do you mean by that?

A. It was an odd strain. It was a strain something out of the ordinary.

Q. What do you mean by that?

A. It was syncopated in a different way.

Q. How does the syncopation of this number differ from the other rag time numbers now on the market?

A. It is a different rhythm in certain spots.

Q. What spots?

A. Different spots, especially the interlude. …

Q. Can you describe the character of this strange strain that was composed?

A. It was a weird strain.119

No recordings exist of Brown’s Band From Dixieland from 1915, so we can only imagine what that “weird strain” and those syncopated rhythms sounded like.

Brown’s Band continued playing at the Lambs’ Café until August 28, when Corbett temporarily closed his place for renovations, enlarging it from 250 to 400 tables.120 Brown and his fellow musicians started calling themselves the Ragtime Rubes, playing for a while with Frisco and hitting the road. They broke up in early 1916.121

Brown’s Band poses with Frisco later in 1915, when the group was going by other names, including the Ragtime Rubes. Louisiana Digital Library.

Did Gordon Seagrove see Brown’s Band?

But Brown’s Band was still playing at the Lambs’ Café in July 1915, when a story by Gordon Seagrove appeared in the Tribune, describing new styles of music called jazz and the blues, or jazz blues. (See Chapter 11.) Brown’s Band may well have inspired Seagrove to write that story.

But Brown’s Band was still playing at the Lambs’ Café in July 1915, when a story by Gordon Seagrove appeared in the Tribune, describing new styles of music called jazz and the blues, or jazz blues. (See Chapter 11.) Brown’s Band may well have inspired Seagrove to write that story.

Lopez’s recollections and Sudhalter’s 1999 book describe Brown’s Band as a smashing success during its time at the Lambs’ Café. In contrast, H.O. Brunn’s 1960 book The Story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band asserted that “the history of Brown’s band reads like a textbook of failures,” adding: “The attendance at Lamb’s Cafe dwindled steadily.”122

It’s impossible to know exactly how popular the band was during the spring and summer of 1915. Did the Eastland Disaster, when 844 passengers died as a boat capsized in the Chicago River on July 24, 1915, cast a pall on attendance at the city’s entertainment shows, including the performances by Brown’s Band? Perhaps. This was also at a time when headlines about the war in Europe dominated the pages of Chicago newspapers. And yet, it’s also when a wilder kind of nightlife was shaking up the city.

It doesn’t appear that any Chicago newspapers wrote about Brown’s Band, but that’s not unusual. Most of Chicago’s live music happened without any reviews or notices appearing in the city’s newspapers. Looking through those papers now, we can catch only a few glimpses of what was going on.

Seagrove’s article doesn’t offer definitive proof that Brown’s Band was attracting attention at the Lambs’ Café. But it certainly seems to suggest it. Can it be just a coincidence that Seagrove wrote his story about the emergence of a new style of music called jazz at the exact moment when Brown’s Band From Dixieland was performing at a prominent downtown cabaret?

Did Seagrove attend a show at the Lambs’ Café? Or did he hear a band somewhere else that was imitating Brown’s Band? Seagrove asserted that “blue music” had “become the predominant motif in cabaret offerings” over the few months leading up to July 1915, and it was now “heard in every gin mill where dancing holds sway.” That seems like hyperbole. Then again, it’s possible that other musicians in Chicago were already mimicking these new sounds arriving from New Orleans. And other musical acts, ranging from Jelly Roll Morton to Bert Kelly, were bringing jazzy and bluesy sounds to the Windy City.

Where had the piano player quoted in Seagrove’s article (“Marion”) heard blues and jazz? Did he attend a show by Brown’s Band? Did he venture into the South Side’s black-and-tan cabarets and hear African Americans musicians? Or did he learn it secondhand or third-hand from other white musicians? We can only guess. But Lopez’s story about Lyon & Healy offers a clue. Was Lyon & Healy one of the music stores that Seagrove visited on his quest to learn the meaning of jazz? Or maybe that music publishing office across the street from the Lambs’ Café, mentioned by Charles Collins?

After Seagrove wrote about jazz on July 11, 1915, the word did not immediately become commonplace. It didn’t appear in any other newspaper articles—as far as we can tell—until the following spring, when another band arrived in Chicago from New Orleans, calling itself Stein’s Dixie Jass Band. The word jazz finally began popping up in more newspaper stories in the fall of 1916.

If Seagrove was correct about the music’s popularity in July 1915, why didn’t anyone else notice this phenomenon and write about jazz? This may simply be an indictment of how unobservant most journalists were in 1915 when it came to popular music. It also may reflect how Seagrove was exaggerating when he described a jazz and blues boom. Was he ahead of his time? For all of his flaws as a journalist—the many silly articles he’d authored featuring quasi-fiction protagonists and peculiar in-jokes—Seagrove noticed something big was happening in American popular music at a time when no other reporters bothered to look.

And what about that other new thing that Seagrove wrote about, a style of music called the blues? More about that in the next chapter.

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Footnotes

1 Dick Holbrook, “Our Word JAZZ,” Storyville 50 (December 1973), 49, https://nationaljazzarchive.org.uk/explore/journals/storyville/storyville-050/1267315.

2 Ben Zimmer, “How Baseball Gave Us ’Jazz,’” Boston Globe, March 25, 2012.

3 Howard Reich and William Gaines, Jelly’s Blues: The Life, Music, and Redemption of Jelly Roll Morton (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2003), 41, 42, 45; “Tony Jackson (Pianist),” Wikipedia, accessed June 16, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_Jackson_(pianist).

4 Richard M. Sudhalter, Lost Chords: White Musicians and Their Contribution to Jazz, 1915-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 10; “Freddie Keppard,” Wikipedia, accessed July 12, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freddie_Keppard.

5 “Joe Jordan,” Wikipedia, accessed July 16, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joe_Jordan_(musician).

6 William Howland Kenney, Chicago Jazz: A Cultural History 1904-1930 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 8; Sudhalter, Lost Chords, 10; “Wilbur Sweatman,” Wikipedia, accessed July 15, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilbur_Sweatman.

7 Kenney, Chicago Jazz, xii, xiii, 4, 5, 11; Genevieve Reuben, “Badger State,” Chicago Defender, September 16, 1916, 12.

8 Oxford English Dictionary, online version, March 2023; “Estella Harris,” Chicago Defender, September 30, 1916, 3.

9 Robert Goffin, translated from French by James F. Bezou, Horn of Plenty: The Story of Louis Armstrong (New York: Allen, Towne & Heath, 1947), 110-111. https://archive.org/details/hornofplenty0000robe/

10 “Jass and Jassism,” editorial, New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 20, 1918, 4.

11 “Orleans’ Product: ‘Stale Bread’s’ Fiddle Gave ‘Jazz’ to the World,” New Orleans Item, March 9, 1919, magazine, 5.

12 Herbert Asbury, The French Quarter: An Informal History of the New Orleans Underworld (New York: Garden City Publishing, 1938), 437-438, https://archive.org/details/frenchquarter0000herb/page/436/mode/2up.

13 Ray Lopez (as told to Dick Holbrook), “Mister Jazz Himself,” Storyville 64 (April-May 1976), 138, https://nationaljazzarchive.org.uk/explore/journals/storyville/storyville-064/1267477.

14 Holbrook, “Our Word JAZZ,” 47-48.

15 Charles H. Wheeler, “Sidelights on Shows Billed for the Coming Week,” Winnipeg Tribune, June 28, 1913, section 2, 12, quoting San Francisco Chronicle.

16 “A Lexical History of ‘Jazz,’” Word Matters podcast, episode 39, accessed June 16, 2023, https://www.merriam-webster.com/word-matters-podcast/episode-39-jazz.

17 “Bert Kelly (Jazz Musician),” Wikipedia, accessed July 9, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bert_Kelly_(jazz_musician).

18 Bert Kelly, letter to editor from New York, “Bert Kelly Stakes Claim to Heading 1st Jazz Band in Chicago Back in’14,” Variety, October 2, 1957, 64, https://archive.org/details/variety208-1957-10/page/n63/mode/2up.

19 Advertisement, Chicago Daily News, January 12, 1917, 7.

20 Elijah Wald, How the Beatles Destroyed Rock n Roll: An Alternative History of American Popular Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 56-57.

21 Walter J. Kingsley, “Jazz Has Remarkable History as a Fad,” (New York) Sun, February 9, 1919, section 6, 6, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030431/1919-02-09/ed-1/seq-72/#date1=1836.

22 Kitty Kelly, “Flickerings From Film Land,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 20, 1915, 13; Kitty Kelly, “Flickerings From Film Land,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 22, 1915, 10; Kitty Kelly, “Film Stars Glow at Movie Ball,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 23, 1915, 13; “Reel Fellows Stage First Ball,” Motography 13, no. 10 (March 6, 1915): 347-350, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433034835631?urlappend=%3Bseq=398%3Bownerid=13510798903613635-436.

23 “Benson Orchestra of Chicago,” Wikipedia, accessed July 12, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benson_Orchestra_of_Chicago.

24 “Reel Fellows Stage First Ball.”

25 Richard M. Sudhalter, Lost Chords, 3.

26 Joe Swerling, “Young Man From Dubuque,” New Yorker, September 26, 1925, 9.

27 Percy Hammond, “‘A Modern Eve’ Shows Signs of Life,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 22, 1912, 11.

28 Swerling, “Young Man From Dubuque,” 9.

29 “Joe Frisco,” Wikipedia, accessed July 29, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joe_Frisco; F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925), 49. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/penn.ark:/81431/p3k06x69r?urlappend=%3Bseq=59.

30 Examination of Louis Joseph, Hart et al. v. Graham (N.D. Ill. 1917), Case File E914; U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division (Chicago); Records of District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21; National Archives and Records Administration Great Lakes Region (Chicago). Transcription in Katherine Murphy Maskell, “Who Wrote Those ‘Livery Stable Blues’?: Authorship Rights in Jazz and Law as Evidenced in Hart et al. v. Graham,” master’s thesis, Ohio State University School of Music, 2012, https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_etd/send_file/send?accession=osu1338343959&disposition=inline, 153-154; H.O. Brunn, The Story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1960), 26.

31 Swerling, “Young Man From Dubuque,” 9.

32 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 138.

33 Sudhalter, Lost Chords, 751n9.

34 Trav S.D., “John Swor: His Relatives Made Me Take The Photograph Down,” Travalanche, accessed August 2, 2023, https://travsd.wordpress.com/2013/11/23/stars-of-vaudeville-842-john-swor/.

35 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 139.

36 Deposition of Tom Brown, Hart v. Graham, Maskell transcription, 131.

37 “Orleans’ Product.”

38 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 140, 142.

39 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 139, 142.

40 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 142.

41 Examination of Louis Joseph, Hart v. Graham, Maskell transcription, 154.

42 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 142.

43 Advertisement, Chicago Examiner, May 15, 1915, 17.

44 Sudhalter, Lost Chords, 7.

45 John Kelley, “Lions of Lambs Sing Dirge of Noted ‘K. and K.,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 15, 1919, part 2, 10.

46 Charles Collins, “The Streets of the Town: Randolph: From Past to Present,” Chicagoan 7, no. 3 (April 27, 1929), 16, http://pi.lib.uchicago.edu/1001/dig/chicagoan/mvol-0010-v007-i03/17.

47 1915 Chicago city directory, Fold3.com; Chicago white pages, October, 1912; white pages, February 1914; yellow pages, July 1914, Library of Congress; Chicago, Vol. 1, South Division (Sanborn Map Company, 1906), 16, https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4104cm.g01790190601S/?sp=17&st=image&r=0.308,0.682,0.268,0.156,0.

48 Collins, “Streets of the Town.”

49 Rand, McNally & Co.’s Bird’s-Eye Views and Guide to Chicago (Chicago: Rand, McNally & Co., 1893), 116-117, https://archive.org/details/randmcnallycosbi00lawr/page/116/mode/2up.

50 “A Line o’ Type or Two,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 10, 1939, 16.

51 “The Lambs,” Wikipedia, accessed July 13, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Lambs.

52 “A Line o’ Type or Two,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 10, 1939, 16.

53 Collins, “Streets of the Town.”

54 Kelley, “Lions of Lambs.”

55 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 142.

56 “A Line o’ Type or Two,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 25, 1949, 18.

57 Chicago Eagle, October 9, 1915, 5.

58 Collins, “Streets of the Town.”

59 1915 Chicago city directory, 129, 372, Fold3.com.

60 LeRoy Blommaert, “The Edgewater Beach Hotel: From Idea to Reality,” Edgewater Historical Society, http://www.edgewaterhistory.org/ehs/local/edgewater-beach-hotel-idea-reality; “Smiley Corbett Dies as He Lived With a Smile,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 6, 1920, 3.

61 Chicago Eagle, October 9, 1915, 5.

62 “Smiley Corbett Dies as He Lived With a Smile,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 6, 1920, 3.

63 Collins, “Streets of the Town.”

64 Edna Ferber, “The Gay Old Dog,” in Edward J. O’Brien, ed., The Best Short Stories of 1917 and the Yearbook of the American Short Story (Boston: Small, Maynard & Company, 1918), 208, https://archive.org/details/TheGayOldDog/mode/2up.

65 Kelley, “Lions of Lambs”; “Smiley Corbett Dies as He Lived”; Charles H. Hermann, Recollections of Life & Doings in Chicago From the Haymarket Riot to the End of World War I by an Old Timer (Chicago: Normandie House, 1945), 125-126; Hugh S. Fullerton, “Dugan Club—White Sox Rooters—Extends to All Parts of the World,” Daybook, November 12, 1914, 23-24; Charles Cowdery, “Lake Whiskey: The Marvel That Was Chicago’s Chapin & Gore,” Newcity, March 8, 2023, https://resto.newcity.com/2023/03/08/lake-whiskey-the-marvel-that-was-chicagos-chapin-gore/.

66 “Packey’s Mother Happy, but Says It Is Last Fight,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 12, 1915, III, 1.

67 “Has Moran Chance to Beat Johnson in Paris Battle?” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 25, 1914, 13, 14.

68 “US boxer Jack Johnson beats Frank Moran in Paris – archive, 1914,” Guardian, June 29, 1914, posted online June 29, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2017/jun/29/jack-johnson-beats-frank-moran-boxing-match-paris-1914.

69 “Denied New Year’s Picture; Film Man Sues for $25,000,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 18, 1912, 18.

70 “Wins $1,200 From Lambs,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 18, 1915, 13.

71 Charles J. McGuirk, “Why Do You Go Wild Over ‘Dixie’?” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 25, 1914, part 7, 5.

72 Sudhalter, Lost Chords, 7.

73 Patricia Wheeldon Caudill Family Tree, accessed July 17, 2023; 1880 U.S. Census, Louisiana, Orleans, New Orleans, Enumeration District 019, 20; U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, Ancestry.com.

74 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 136.

75 Examination of Louis Joseph, Hart v. Graham, Maskell transcription, 153-154; Brunn, Story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, 26.

76 Advertisements, Chicago Herald, May 20, 21, and 22, 1915, 5.

77 Susan Figliulo, “The Marx Brothers House,” Chicago Reader, May 18, 2000, https://chicagoreader.com/news-politics/the-marx-brothers-house/.

78 “‘Everybody Rag With Me’ and Al Jolson Big Hits at the Garrick,” Chicago American, May 19, 1915, special extra, 8.

79 “‘Everybody Rag With Me’ Song Hit,” Chicago American, May 20, 1915, special extra, 12.

80 Advertisement, Chicago Evening Post, May 22, 1915, 6.

81 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 142.

82 “Orleans’ Product.”

83 1915 Chicago city directory, 1258, Fold3.com; Sudhalter, Lost Chords, 7-8; Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 143.

84 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 143.

85 Examination of Louis Joseph, Hart v. Graham, Maskell transcription, 154; Brunn, Story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, 26.

86 “Orleans’ Product.”

87 Sudhalter, Lost Chords, 7.

88 Alan P. Merriam and Fradley H. Garner, “Jazz—The Word,” Ethnomusicology 12, no. 3 (1968): 389. https://doi.org/10.2307/850032. Cited sources: Charles Edward Smith, “White New Orleans,” in Frederic Ramsey Jr. and Charles Edward Smith, eds., Jazzmen (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1939), 46; “Tom Brown, leader in Dixieland Jazz,” New York Times, March 26, 1958, 37.

89 Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis, They All Played Ragtime (New York: Oak Publications, 1971), 149-150.

90 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 144.

91 “Dave Knost Beats Jack M’Auliffe in Fight at Armory,” St. Louis Star, March 16, 1929, 10.

92 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 143.

93 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 145.

94 Ray Pearson, “Pugilistic Pointers,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 14, 1919, 16.

95 Knockout, “Kelly Works Out for Bout,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 25, 1911, 21.

96 “Promoters of Fiasco Take to Fire Escape,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 12, 1926, 21, 22.

97 Howard Carr, “Latest News and Gossip of Fights and Fighters,” Inter Ocean, April 8, 1913, 13.

98 Howard Carr, “Latest News and Gossip of Fights and Fighters,” Inter Ocean, January 20, 1914, 13.

99 “Honor Men See Open Air Boxing Bouts at Joliet,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 6, 1915, 11.

100 “Pugilistic Pointers,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 6, 1915, 12.

101 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 143.

102 “Company History,” Lyon & Healy, accessed August 1, 2023, https://www.lyonhealy.com/lyon-healy-harps/harps-maker-company-history/.

103 1915 Chicago city directory, 1022, Fold3.com.

104 “Lyon & Healy,” Chicagology, accessed August 1, 2023, https://chicagology.com/lyonhealy/.

105 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 143-144.

106 Advertisement, Chicago Examiner, May 22, 1915, 17.

107 “Arthur Greiner,” Wikipedia, accessed August 2, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Greiner.

108 Swerling, “Young Man From Dubuque,” 9-10.

109 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 144.

110 Advertisement, Chicago Examiner, May 26, 1915, 15.

111 Advertisements, Chicago Examiner, June 2, 1915, 13; June 5, 1915, 17; June 9, 1915, 15; June 12, 1915, 15; June 16, 1915, 13; June 19, 1915, 13.

112 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 145.

113 Kelly, “Bert Kelly Stakes Claim.”

114 Deposition of Bert Kelly, Hart v. Graham, Maskell transcription, 127.

115 Kingsley, “Jazz Has Remarkable History”; “Orleans’ Product.”

116 Sudhalter, Lost Chords, 13.

117 “Orleans’ Product.”

118 Swerling, “Young Man From Dubuque,” 9.

119 Testimony of Raymond E. Lopez, Hart v. Graham, Maskell transcription, 232, 240-241.

120 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 144-145.

121 Deposition of Bert Kelly, Hart v. Graham, Maskell transcription, 127.

122 Brunn, Story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, 28.