Chapter 11 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

The next three chapters are a bit of a detour, exploring the origins of jazz and blues (the musical genres as well as the words describing them). Be warned that these chapters include some old words and pictures that are now recognized as racist and offensive.

In the summer of 1915—a year after Green Mill Gardens opened—Chicagoans began hearing a new word. Describing a new style of music, the word itself sounded weird and energetic, almost like a jolt of electricity: jazz.

From the moment when people first heard of jazz, they asked questions about what exactly it meant—and where this word had come from. More than a century later, historians, linguists, and musicologists are still trying to get to the bottom of that puzzle.

One of the most important clues in this etymological mystery is a story that appeared in the Chicago Daily Tribune on July 11, 1915, under the headline “Blues Is Jazz and Jazz Is Blues.” According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this Tribune story was the first known time that the word jazz ever appeared in print as a musical term.

Now, of course, this doesn’t mean it was the first time anyone wrote about jazz music. It’s merely the earliest printed example of the musical term that researchers have found so far. Older examples could turn up.

Now, of course, this doesn’t mean it was the first time anyone wrote about jazz music. It’s merely the earliest printed example of the musical term that researchers have found so far. Older examples could turn up.

The word jazz had been circulating on the West Coast a few years earlier, when baseball players used it as a slang term with a meaning similar to pep. By the time the Tribune wrote about jazz in 1915, some musicians in Chicago were using the word.

In 1916, the word started popping up in other articles and advertisements, sometimes spelled jaz, jas, or jass. In 1917, the word jazz exploded into popularity, along with the music it described, becoming a nationwide phenomenon.

And jazz became the standard spelling. As the Chicago Daily News explained: “The ‘z’s’ you gotta double, / To give it ‘zip’ and bubble.”1

Suddenly, it seemed like everyone was playing jazz or dancing to it—except for the people denouncing it as evil. Musicologists may quibble about whether all of the music described as jazz in this era truly meets the definition of jazz. Was the vaudeville singer-violinist Isabella Patricola, a mainstay at Green Mill Gardens, really performing “jazzy jazz,” as one newspaper put it?2

“The term’s exact meaning has been notoriously elusive, covering, both then and now, a wide variety of different musical styles and provoking substantial disagreement,” William Howland Kenney wrote in Chicago Jazz: A Cultural History 1904-1930.3

When I asked the Green Mill jazz club’s current owner, Dave Jemilo, about this, he said: “When was jazz called jazz? That’s the thing.” As he pointed out, when Green Mill Gardens opened in 1914, “Jazz wasn’t even called jazz yet.”

Gordon Seagrove, the author of that 1915 Tribune story, didn’t invent the word jazz. He’d apparently heard people talking about it, and then he investigated what it meant. He also tried to pin down the meaning of another musical term that was new at the time, blues. He arrived at a conclusion that might seem surprising—or just plain wrong—to us today: that jazz and blues were the same thing.

Seagrove’s article “was a pretty silly effort,” music historian Elijah Wald observed.4 Yes, it’s silly. And yet, it’s historically important—and worth deciphering. The story is confusing at first glance. It opens with a scene at a cabaret or a similar sort of entertainment venue, where a band is performing and a couple is sitting at a table. Seagrove didn’t say exactly where this was. The whole scene reads as if it could be fiction, similar to some of the other articles Seagrove had written for the Tribune.

For a better understanding of Seagrove’s article about jazz and blues, it’s worth looking at just who this journalist was. Born in Spring Lake, Michigan, Gordon Kay Seagrove was 24 and single at the time he wrote this story,5 a tall and slender man with blond hair and blue eyes.6 He lived with his parents at 4866 North Sheridan Road, about seven blocks away from Green Mill Gardens,7 a place he mentioned in his reporting.8

Seagrove’s father ran the Seagrove-Christiansen Company,9 a “secret service” of detectives and strikebreakers. “They have as fine a lot of gunmen as any strikebreaking agency in the country,” a railroad union leader remarked, expressing grudging admiration for these foes of organized labor. “Our organization knows because our men have felt the string of bullets shot by the Seagrove-Christianson men.” Seagrove’s younger brother, George, was arrested when he was 15 for carrying around an automatic pistol.10

Seagrove started writing for the Tribune by 1910, when he was just 19, and he eventually became an editor. Later, he owned an advertising business11 and was known for his exploits as an “ardent sailor” on yachts in Lake Michigan,12 a hobby he was already pursuing in 1915. Three months after he wrote his groundbreaking article on jazz and blues, Seagrove was the subject of a front-page headline in his own newspaper: “Yacht Party in Peril Two Nights on Lake.”

Seagrove’s boat, the Nymph, had run into stormy weather on the way to Milwaukee. Sailing with his brother and three friends, Seagrove was tossed around on the lake for two days before they finally made it safely back to land.13

Seagrove did some reporting on serious topics—including an article about missing Chicago women14 and another one about killings in Little Italy15—but he usually wrote feature stories on lighter subject matter, acting at times as a sort of man-about-town correspondent covering Chicago’s nightlife and romances.

A week before his report about jazz music, Seagrove had chronicled the efforts of some young men he called “Wilson avenue bon vivants” to achieve the perfect look for their pompadours. He described two men named Clarence and Hubert combing their hair repeatedly at midnight. “One hundred strokes—no less,” Clarence murmured. (It seems unlikely that Seagrove actually witnessed this.) Before going to bed, these fastidious scenesters covered their wet hair with small skullcaps, so that they’d wake up with their hair looking just right. According to Seagrove, “The large end of a silk stocking cut off and sewed in a circular form finds great popularity on the north side, in the Wilson avenue belt.”16

A week before his report about jazz music, Seagrove had chronicled the efforts of some young men he called “Wilson avenue bon vivants” to achieve the perfect look for their pompadours. He described two men named Clarence and Hubert combing their hair repeatedly at midnight. “One hundred strokes—no less,” Clarence murmured. (It seems unlikely that Seagrove actually witnessed this.) Before going to bed, these fastidious scenesters covered their wet hair with small skullcaps, so that they’d wake up with their hair looking just right. According to Seagrove, “The large end of a silk stocking cut off and sewed in a circular form finds great popularity on the north side, in the Wilson avenue belt.”16

Seagrove also wrote a commentary about the clichés of vaudeville songs. “These songwriters are a fickle lot, whose duplicity knows no ends and whose sins do not end with rhyming ‘lady’ and ‘baby,’” he wrote, complaining that too many songs featured lyrics pining for distant places. By his estimate, 60 percent of all songs in Chicago vaudeville shows mentioned “Dear Old Ireland,” 20 percent California, 10 percent “Araby,” and 10 percent Kentucky.

“Only last night six different actors came out and told us through their noses that we were boobs for staying here in Chicago when we might be bathing in Irish lakes in the dead of winter,” he wrote. “They had scarcely finished when five more came on and attempted to lay Ireland out cold with rival ditties about California, bidding us to come straightaway to San José and San Francisco.”17

For another story, Seagrove joined a matchmaking service and wrote a hundred letters to women who were seeking husbands—and then printed their responses, filling up two entire pages of the Tribune. He concluded by confessing that he was “like the fellow who kisses and tells.” Seagrove said of himself: “He is no gentleman. He admits it.”18

Seagrove’s articles for the Tribune also included humorous poetry (“The Addled Ad Man”19) and narratives starring characters such as Orville, the Boy Bookkeep, who catches “the vaudeville bug”20 before growing tired of the “frivolity of life.”21 Like Seagrove’s 1915 story about jazz and blues, these articles can be read as fiction, but they may be based on observations of real people.

It’s a particular type of writing that was common in late 19th-century and early 20th-century newspapers, practiced by Chicago scribes like George Ade and Ben Hecht. These journalists wrote stories based on people and events they saw in Chicago, but they took liberties as they fashioned these observations into stories that read like scenes from novels.

And so, when Seagrove wrote about a couple sitting at a table while a band played music nearby, how should we understand what he’s describing? Who are these people? Did he transcribe or paraphrase these words from an actual conversation he overheard? Or did he concoct two fictional characters, placing them in a scene similar to situations he’d observed in real life? It’s hard to say for certain.

Seagrove did not give the woman a name. She called her husband by an unusual name, Ortus, but the story refers to him as “the Worm.” Perhaps Seagrove called him that simply so could say “the worm turned,” an old expression about a person’s situation suddenly changing for the better. Or maybe these odd monikers, Ortus and the Worm, are jokes with some other meaning, now lost to history. Seagrove isn’t alive for us to interrogate. (“Gordon! What the hell were you talking about?”)

As the Worm sat with his wife, he was tired from a day of work. His wife wanted to dance. “Ortus, she murmured, looking into his tired eyes, “if you don’t fox trot with me shortly I shall bring suit for divorce. Our life cannot go on this way.”

But then the band started playing jazz and blues (which were the same thing, as far as Seagrove was concerned). Seagrove described how this music transformed the Worm, enlivening the enervated man:

Suddenly from above the thread of the melody itself came a harmonious, yet discordant wailing, an eerie mezzo that moaned and groaned and sighed and electrified, a haunting counter strain that oozed from the saxaphone [sic].

The Worm stopped. His eyes shone with a wonderful light—the light that lies in the eyes of a man who has had two around the corner. His mouth moved convulsively. The years fell away from his shoulders leaving only his frock coat.

The Worm had turned—turned to fox trotting. And the “blues” had done it. The “jazz” had put pep into the legs that had scrambled too long for the 5:15.

What mattered to him now the sly miles of contempt that his friends had uncorked when he essayed the foxy trot a month before; what matter it whose shins he kicked?

That was what “blue” music had done for him.

Seagrove’s article didn’t describe the musicians who were playing this music. It said nothing about whether they were Black or white. If any of these people were African American, a Tribune story of that era almost certainly would have pointed out that fact, so we can reasonably assume that Seagrove was writing about white people.

Seagrove’s article didn’t describe the musicians who were playing this music. It said nothing about whether they were Black or white. If any of these people were African American, a Tribune story of that era almost certainly would have pointed out that fact, so we can reasonably assume that Seagrove was writing about white people.

But a cartoon accompanied the story, depicting a Black saxophonist—with the stereotypical facial features that were common in depictions of African Americans during that era.

The sound coming out of the instrument was spelled out as “WOOO OOO OOO!” A caption explained: “A blue note is a sour note.”

Another drawing depicted the white man whose spirits were lifted by this music.

Another drawing depicted the white man whose spirits were lifted by this music.

Seagrove reported that jazz and blues—or as he also called it, “‘blue’ music”—had become the dominant styles of music at Chicago cabarets over the previous few months.

Note how Seagrove explained that “blue music” worked like a cure for “the blues.”

That is what “blue” music is doing for everybody—taking away what its name implies, the blues. In a few months it has become the predominant motif in cabaret offerings; its wailing syncopation is heard in every gin mill where dancing holds sway.

Its effect is galvanic. Cripples take up their beds and one-step; taxi drivers willingly suffer sore feet because of it; string halt become St. Vitus’ dance in its grip.

Seagrove then explained how he’d set out to define just what the “blues” and “jazz” were:

Maybe you, pour soul, in your metropolitan ignorance, do not gather just what the “blues” are. Worry not; neither does the average person that plays them and it was only after weeks of toiling that the true definition was obtained.

Although Seagrove said his investigation entailed “weeks of toiling,” he described visiting just two places to ask people about the meaning of these words. It sounds more like an hour’s work—but who knows how much time Seagrove spent looking around Chicago for someone to answer his riddle? Of course, it’s possible he was fictionalizing or embellishing the second half of his article, much as he seemed to do with the first half.

The first place Seagrove went on his quest was “a song publisher’s arena, where beautiful actresses try their voices and the manager’s nerves.” This seems to be Seagrove’s way of describing a music publisher’s office, where composers would try selling their songs.

Seagrove directed his question at a dark-haired piano player: “What are the blues?”

The young musician “recoiled and shuddered,” according to Seagrove, who was probably exaggerating for humorous effect.

The pianist replied: “I don’t know. All I can do is play ’em. A kind of a wail you might call it. Still I couldn’t tell you positively. But, say! I can take any piece in the world and put the blues into it. But as for a definition—don’t ask me.”

Seagrove then went to a place where “a young woman was keeping ‘Der Wacht Am Rhein’ and ‘Tipperary Mary’ apart.” Once again, Seagrove was vague and jokey instead of offering clear and forthright details. Was he describing a store selling sheet music or phonographs and player piano rolls? A music publishing office? Was this woman situated between people playing German and Irish music? Wherever and whatever this place was, the woman was not far away from a tall young man playing a piano.

When Seagrove asked, “What are the blues?” the woman exclaimed, “Jazz!”

Now, that’s a rather curious way of answering the question. Did she assume that someone who didn’t know the definition of “blues” would know the definition of “jazz”? Or was she calling out the nickname of the piano player? Hearing this exchange, the man at the piano came over, saying: “That’s me.”

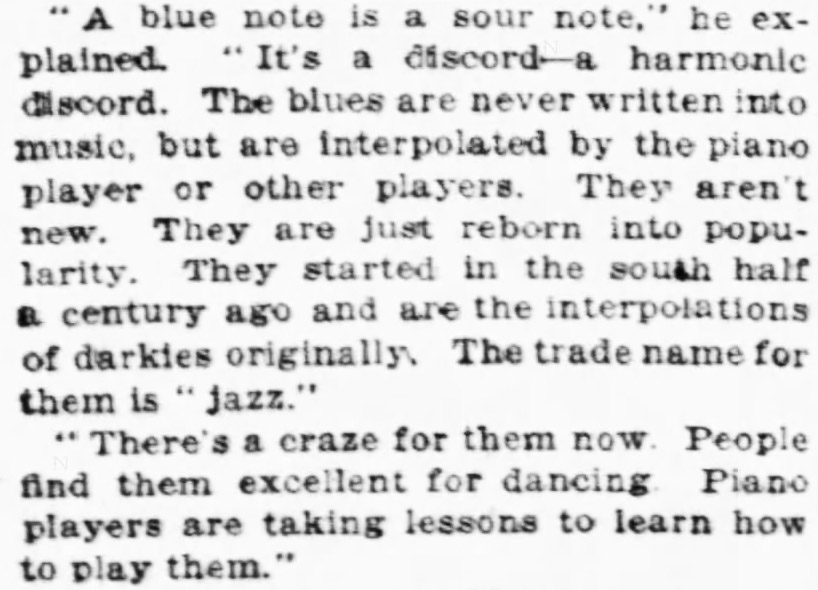

According to Seagrove, the piano player then “unraveled the mystery of the ‘blues,’” giving credit to African Americans (or, as he called them, “darkies”) for developing blues music in the South some 50 years earlier. Here’s how Seagrove reported the man’s answer:

“A blue note is a sour note. It’s a discord—a harmonic discord. The blues are never written into music, but are interpolated by the piano player or other players. They aren’t new. They are just reborn into popularity. They started in the south half a century ago and are the interpolations of darkies originally. The trade name for them is ‘jazz.’

“There’s a craze for them now. People find them excellent for dancing. Piano players are taking lessons to learn how to play them.”

This piano player’s name was apparently Marion. Or was it the woman’s name? In any case, it’s the name Seagrove suddenly introduced at this point in the story.

Thereupon “Jazz” Marion sat down and showed the bluest streak of blues ever heard beneath the blue. Or, if you like this better: “Blue” Marion sat down and jazzed the jazziest streak of jazz ever.

Seagrove then noted how “jazz blues” saxophonists often used devices to change the tone of their instruments:

Saxophone players since the advent of the “jazz blues” have taken to wearing “jazz collars,” neat decollete things that give the throat and windpipe full play, so that the notes that issue from the tubas may not suffer for want of blues—those wonderful blues.

Finally, Seagrove concluded:

Try it some time—for that tired feeling—the blues.22

Despite what Seagrove wrote in this 1915 article, jazz and the blues are now widely recognized as two separate and distinct genres of music. But the genres are hard to define and they sometimes overlap. Their definitions may have been even more slippery back in 1915.

Seagrove’s story focused almost entirely on one aspect of the music: discordant, “sour,” “wailing” notes. But that’s merely one element of blues and jazz. Seagrove didn’t say anything other keystones of the music, such as the rhythms. When Seagrove described how this music compelled people to dance, that was clearly an effect of the rhythms, even if Seagrove suggested that the wailing notes themselves were the thing that got people moving.

Almost in passing, Seagrove dropped in a possible clue about the origin of the word jazz. Note that he wrote: “The ‘jazz’ had put pep into the legs that had scrambled too long for the 5:15.”

Pep.

That’s one of the definitions for the slang term jazz, as it was used by baseball players and sportswriters on the West Coast starting in 1912.

A leading theory is that the word somehow traveled from West Coast baseball parks to Chicago cabarets. Perhaps some musicians heard it in California and brought it with them to Chicago, where the word took on a new meaning, becoming a musical term.

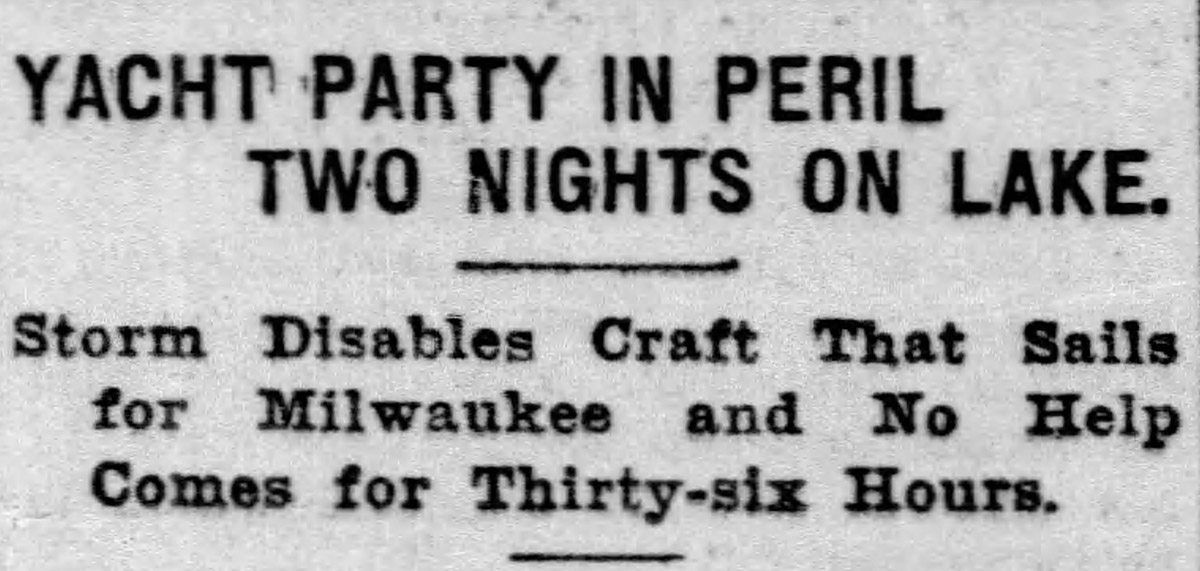

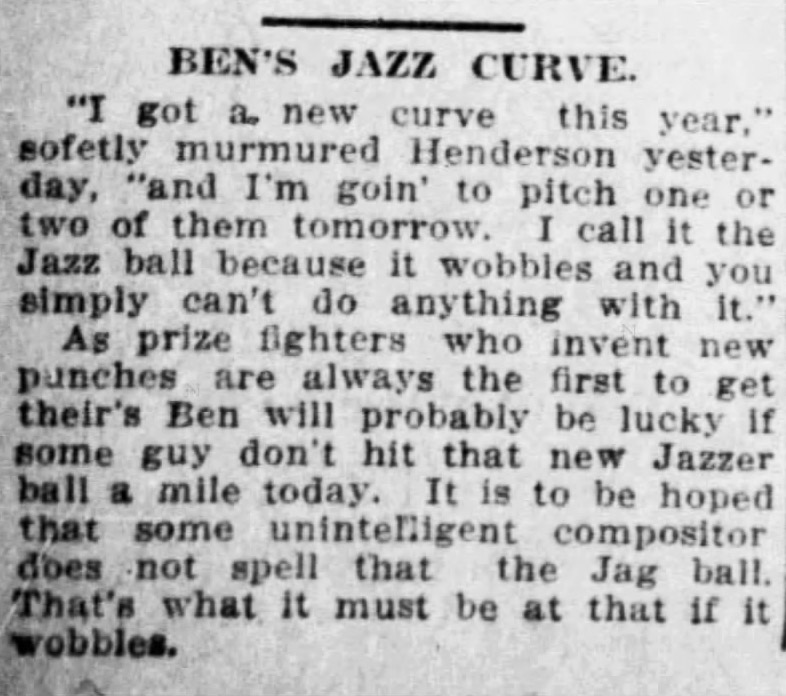

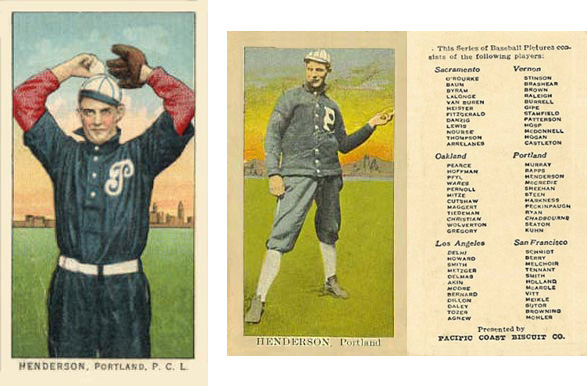

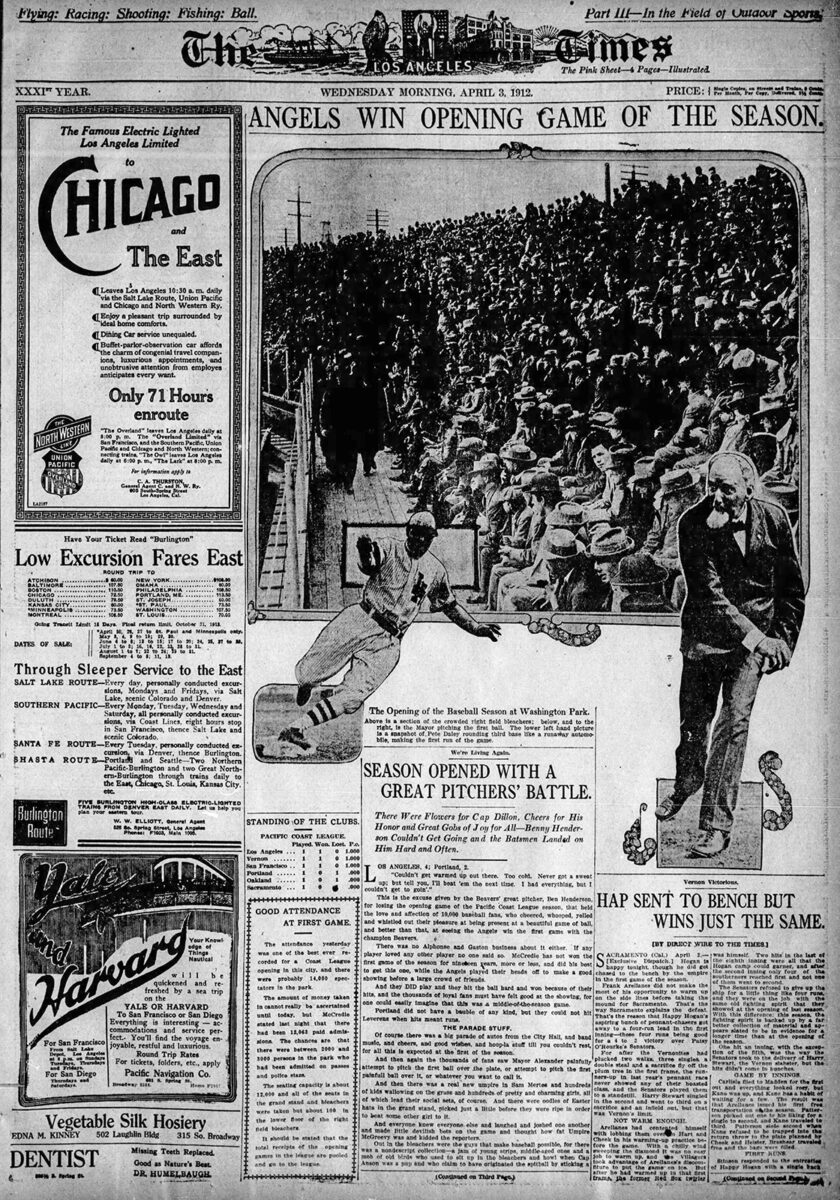

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word jazz made its earliest known appearance in print on April 2, 1912,23 when the Los Angeles Times published an interview with Benny Henderson, a pitcher for the Portland Beavers. He was practicing with his team at Washington Park in L.A. for the opening game of the season, against the Los Angeles Angels.

“I got a new curve this year, and I’m goin’ to pitch one or two of them tomorrow,” Henderson “softly murmured,” according to the Times. “I call it the Jazz ball because it wobbles and you simply can’t do anything with it.”24

Henderson said that as if he expected people to understand what he meant by jazz. Was the word already circulating among baseball players or other people on the West Coast?

James Benjamin Henderson, who was born in 1883 in Iowa, had been playing professional baseball since 1903, spending most of his career on the West Coast, which didn’t have any major league teams in that era.25

The hard-throwing pitcher was tall and handsome—he had “all those dimples that spell ‘beauty’,” one sportswriter commented—26and the Oregon Daily Journal said he had been “one of the best twirlers in the Pacific Coast league.”27 But he was also notorious for getting drunk.

During the 1911 season, he’d won 20 games and lost 12 for the Beavers. 28 He was suspended for “boozing,”29 after he “fell out of the Buttermilk wagon, leaving his team in the lurch,” as one newspaper put it.30

The Beavers’ manager, Walter McCredie, was enraged and disgusted by Henderson’s behavior, calling him “unreliable.” At the season’s end, McCredie predicted: “Benny Henderson has probably played his last game of baseball on the Pacific Coast.”31

But Henderson begged McCredie for another chance. “Benny wrote Manager Mac the other day from his home in Council Bluffs, Ia., stating that he would do whatever the Portland baseball boss wanted of him next year,” the San Francisco Chronicle reported. “Henderson realizes that he did wrong in trying to lap up all the firewater in Los Angeles during the crucial series with Vernon, and is willing to atone for his faux pas with the spiritus fermenti.”

The Beavers signed Henderson to pitch for another season, adding a “booze clause” to his contract. “Henderson will get just enough money next year during playing season to provide him with the necessaries of life,” McCredie explained.32 According to one report, the contract “provided a certain bonus if he maintained a firm seat on the sprinkling cart throughout the season.”33

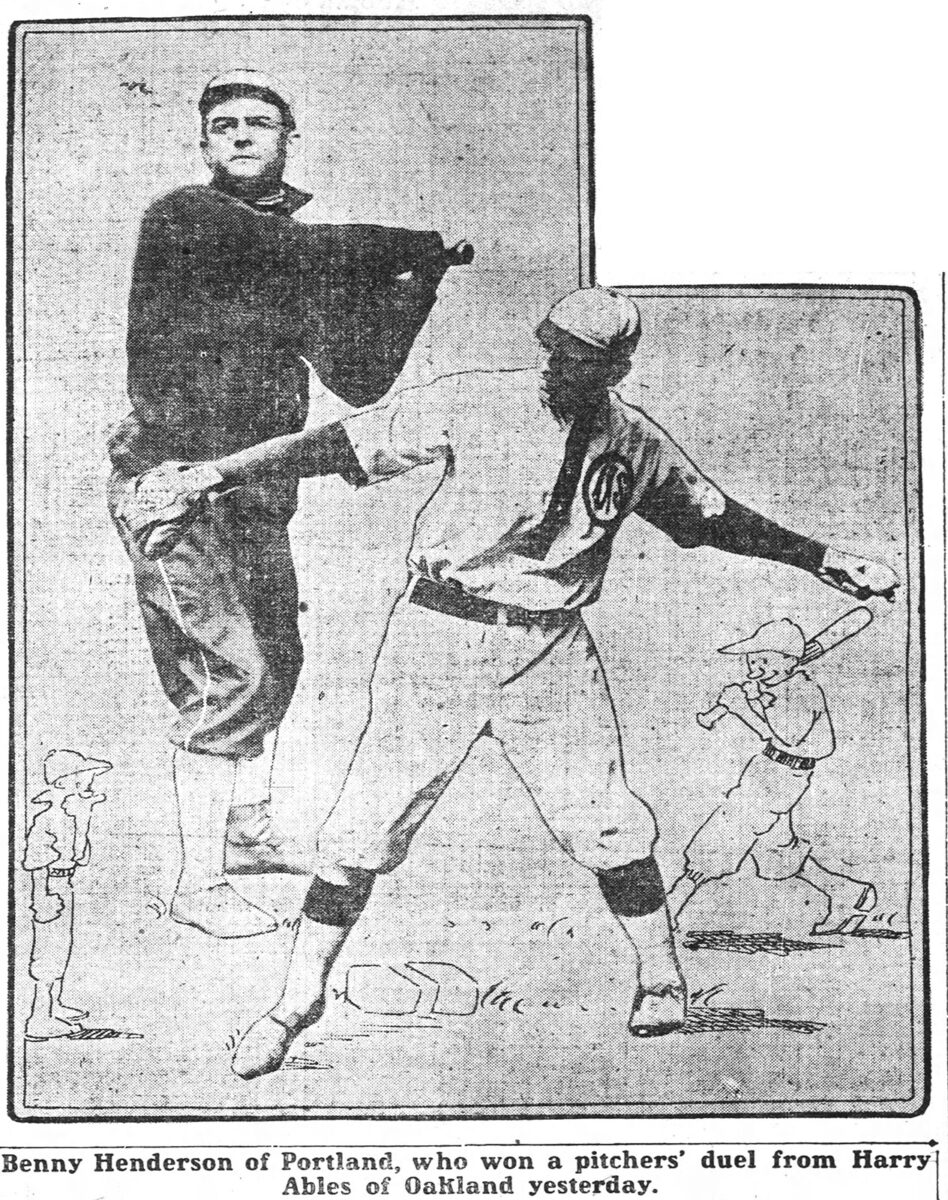

As the 1912 season started, Henderson tried out his “jazz ball.” The Los Angeles Times reporter who interviewed Henderson about the pitch was skeptical that it would prove effective, commenting: “As prize fighters who invent new punches are always the first to get their’s Ben will probably be lucky if some guy don’t hit that new Jazzer ball a mile today.”

The reporter also pleaded with his newspaper’s typesetters not to change the spelling of “jazz ball.” He wrote: “It is to be hoped that some unintelligent compositor does not spell that the Jag ball. That’s what it must be at that if it wobbles.”34

This was a joke about the slang word jag, a common term in that era for drinking binges and drunks. The Los Angeles Times was suggesting here that Henderson’s pitch wobbled like a drunk—and it may have been hinting that Henderson himself was a jag. (I suspect that this meaning of jag had some influence on the slang term jagoff, although there are other theories about where that word came from.)

Why had Henderson “murmured softly” when he told the Times reporter about his jazz ball? Perhaps he was trying to avoid attracting the attention of McCredie, the team’s disciplinarian manager. On the same afternoon, McCredie shouted at the players when they did “some fancy business” during batting practice.

“You blasted buster,” he roared. “What are you trying to do? Don’t you know how to throw a ball? Who ever told you that you could play ball? Do you think that this is a vaudeville stunt, where your fancy acts are applauded? Stop it, I say.” Afterward, when the players went to their hotel, one suggested that they should all go out to dinner in Venice, but McCredie interjected: “In bed at 9 o’clock tonight and lights out at 9:30. Get me?”35

Henderson’s jazz ball didn’t seem to help him much on the mound. He did get six strikeouts during the nine innings he pitched the following day. Times writer Owen R. Bird observed how Henderson got a strike when he “cut the outside corner with a fast curve.” According to Bird, “Benny calls this his ‘jass’ ball.”36

But the game was a loss for Henderson and the Beavers; the Angels won, 4 to 2. “Couldn’t get warmed up out there. Too cold,” Henderson remarked. “Never got a sweat up; but tell you, I’ll beat ’em next time. I had everything, but I couldn’t get goin’.”37

A few weeks later, Henderson was suspended indefinitely for drinking and breaking the team’s training rules.38

“In fact, it is said that Henderson has taken such poor care of himself lately that he is unable to pitch at all,” the Vancouver Daily World reported.39

McCredie remarked: “Ben telephoned the park yesterday, that he was too ill for work, but I have information that he is not keeping in condition, thus his absence from the clubhouse. He will hardly be ready for service for three weeks, so there would be little use of my taking him on the [team’s road] trip.”40

Henderson was finally scheduled to pitch again when the Beavers had a June 9 game in L.A., but the Los Angeles Times reported: “the old trouble seemed to have overtaken him and he failed to show up at the park on this, the day he was given up the chance to make up for his lapse off the water wagon.”41

Henderson ended up with a record of five losses and zero wins in 1912. He never played professional baseball again.42

But jazz, the word that he’d introduced to sportswriters, had a life of its own. Where had Henderson learned this word? Was it something he’d heard in saloons when he was on one of his drinking jags? Did he pick it up in Iowa?

On March 3, 1913, the San Francisco Bulletin used jazz in a description of a promising rookie first-baseman, George McCarl, who also happened to be from Iowa.43

Three days later, the same sportswriter, E.T. “Scoop” Gleeson, reported that the San Francisco Seals were using the word at their training camp in Boyes Hot Springs, California.

“Everybody has come back to the old town full of the old ‘jazz’ and they promise to knock the fans off their feet with their playing,” he wrote. “What is the ‘jazz’? Why, it’s a little of that ‘old life,’ the ‘gin-i-ker,’ the pep …. the enthusiasalum. A grain of ‘jazz’ and you feel like going out and eating your way through Twin Peaks.”

That was probably a reference to two prominent hills near the center of San Francisco, where the digging of the Twin Peaks Tunnel project was about to begin.44

Gleeson also juxtaposed the word with another musical term: “The team … comes pretty close to representing the pick of the army. Its members have trained on ragtime and ‘jazz.’” That may simply be an allusion to ragtime’s fast tempo. Or does it indicate that jazz already had a musical meaning?45

A San Francisco bandleader, Art Hickman, said the Seals started using the word after one player saw water bubbling out of the ground at Boyes Hot Springs and called it “jazz water.”

Speaking in 1919, Hickman remarked: “It has no association with music. It means something effervescent. … Gradually, the word was carried to the ball ground, and when action was wanted, the boys would call out, ‘come on, let’s jazz it up.’ That is how an orchestra with life came to be known as a ‘Jazz orchestra.’ But none of us like the word.”46

A month after the San Francisco Bulletin started using jazz in baseball stories, the word was often heard in the Bulletin’s office, inspiring Ernest J. Hopkins to write a column headlined “In Praise of ‘Jazz,’ a Futurist Word Which Has Just Joined the Language.”

Hopkins later said he’d learned the word from reporter Walter Harrison, who’d heard it “kicked around in a bar.” 47 Hopkins wrote:

The sheer musical quality of the word, that delightful sound like the crackling of a brisk electric spark, commends it. …

“Jazz” can be defined, but it cannot be synonymized. … This remarkable and satisfactory-sounding word, however, means something like life, vigor, energy, effervescence of spirit, joy, pep, magnetism, verve, virility, ebulliency, courage, happiness—oh, what’s the use?—JAZZ. Nothing else can express it.

… “pep,” which tried to mean the same thing but never could, failed. It was a roughneck from the first, and could not wearing evening clothes. “Jazz” is at home in bar or ballroom; it is a true American.48

“Scoop” Gleeson later said he’d picked up the word from San Francisco Call sports editor William “Spike” Slattery: “Spike said he had heard the word used in dice games around the city. Dice shakers would say, ‘That’s the jazz, boy!’ Typifying ‘pep.’”

Bert Kelly, who played banjo in Art Hickman’s band in San Francisco,49 heard a different story from Hickman about the word’s origins.

According to this tale, Hickman bet Slattery $10 that he wouldn’t print jazz in his newspaper, because it was vulgar slang for having sex. Slattery supposedly won the bet by printing the word—but researchers haven’t found any proof that he actually did so.50

Over the years, people have speculated that jazz originated in African American dialect, African languages, Arabic, Creole, French, Spanish, or Bohemian.51

The Oxford English Dictionary suggests that jazz may have come from jasm, which meant “energy, spirit, ‘pep.’” That slang word made its first known appearance in 1860, spoken by a character from New Hampshire in J.G. Holland’s novel Miss Gilbert’s Career. The book includes this exchange, which is surprisingly suggestive for that era:

“Oh! she’s just as full of jasm!” …

“Now tell me what ‘jasm’ is.”

“Well, that’s a sort of word, I guess, that made itself. It’s a good one, though—jasm is. If you’ll take thunder and lightning, and a steamboat and a buzz-saw, and mix ’em up, and put ’em into a woman, that’s jasm.”52

According to OED, jasm may have originated from jism, an American slang term for “energy, strength,” which dated back to at least 1842. Jism took on another meaning by 1899, becoming a vulgar expression for semen and sperm; it has also been spelled chism, chissum, jissom, jizz, gissum, and gism.53

The word jazz itself could mean “copulation.” The oldest known printed examples of this are from 1918,54 but some people said they’d heard it earlier.

“The word jazz was first used as a sex word in California and was a common localism in San Francisco when I arrived there in 1899 and until I left there,” Bert Kelly told musicologist Dick Holbrook decades later. “I shall be glad to swear on oath before a notary public that Jazz used as a sex word was not only used in San Francisco before the [1906] earthquake and fire, but that it was of such common use that it was a localism.”55

Holbrook also found people who recalled hearing the word jazz in New Orleans and Western mining towns at the turn of the 20th century, used as a term for sex—possibly derived from jezebel or the Irish slang bejesus.56

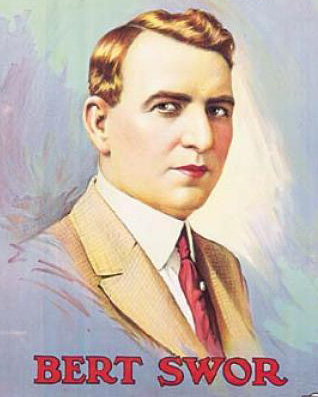

Other people believed that jazz was a shortened version of jazzbo, jazbo, or jasbo. Bert Swor, a white minstrel show performer from Tennessee,57 said a jazzbo was a troupe of Black musicians playing cornet and motley percussion contraptions such as cowbells.58

Bandleader Paul Whiteman said he’d heard a different definition from John Philip Sousa, who believed jazz came from jazzbo, “the term used in the old-fashioned minstrel show when the performers ‘cut loose’ and improvised or ‘Jazzboed’ the tune.”59

OED defines jazzbo as slang for an idiot; a Black person; or “Unsophisticated, unsubtle, or physical comedy; slapstick, esp. in a vaudeville performance.” By 1916, jazzbo also referred to jazz musicians and fans.60

According to various stories, jazzbo and jazz supposedly derived from a specific person’s name—someone named James, Jasper, Jess, Jack, Chas, or Razz.61

One of these stories was told by Chicago music publisher Roger Graham, a white Rhode Islander who’d graduated from dental college and wrote lyrics for 200 songs, including the often-covered 1915 tune “I Ain’t Got Nobody.”62

Graham talked about an African American piccolo and cornet player known as Jasbo Brown who’d played around 1914 at the Schiller Café, 318 East 31st Street. When Brown drank gin, he played his piccolo with “the wildest, most barbaric abandon,” according to the Music Trade Review’s telling of Graham’s tale.

Audience members “liked the thrilling sensation of the piccolo’s lawless strains, and when Jasbo put a tomato can on the end of his cornet it seemed as if the music with its strange, quivering pulsations came from another world.” And so, they bought him drinks to encourage even wilder music, asking him: “More, Jasbo?” And then they insisted, “More, Jasbo!” Finally, they abbreviated their shouts to: “More jazz!”63

That’s the story Graham told, anyway. Graham’s musical career would decline after 1922. He died at Cook County Hospital in 1938, “Alone and Unsung,” as one headline put it. A United Press article noted that this man, whose body was lying in the county morgue, had once written the popular lyrics: “I ain’t got nobody, and nobody cares for me.”64

Was Jasbo Brown a real musician or merely a mythical figure?

Was Jasbo Brown a real musician or merely a mythical figure?

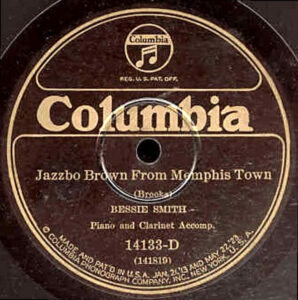

Fletcher Henderson, an African American pianist who grew up in Georgia and worked in New York City65, later wrote a song about a horn player titled “Jazzbo Brown From Memphis Town,” which Bessie Smith recorded in 1926,66 singing: “He ain’t seen no music school / He can’t read a note / But ’s the playin’est fool / On that Memphis boat!”67

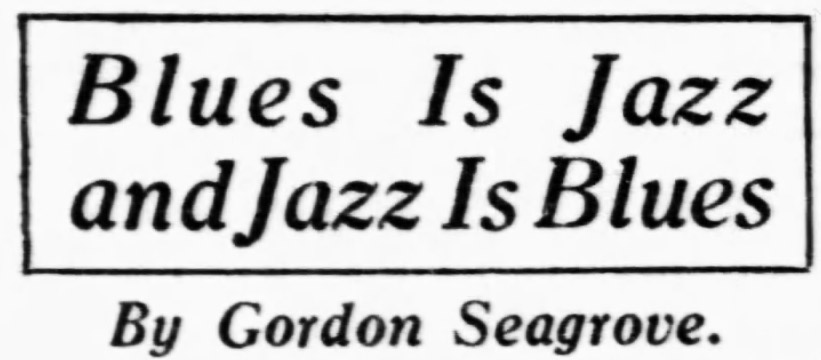

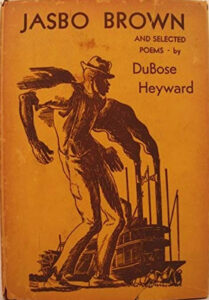

DuBose Heyward, a white author from South Carolina,68 wrote Jasbo Brown and Selected Poems in 1931, describing his title character as an “itinerant negro player along the Mississippi and later in Chicago cabarets.”69

DuBose Heyward, a white author from South Carolina,68 wrote Jasbo Brown and Selected Poems in 1931, describing his title character as an “itinerant negro player along the Mississippi and later in Chicago cabarets.”69

And a piano player named Jasbo Brown appears in the stage directions at the very beginning of George Gershwin’s 1935 opera Porgy and Bess, which has a libretto by Heyward and Ira Gershwin: “Evening, Catfish Row is quiet. Jasbo Brown is at the piano, playing a low-down blues while half a dozen couples dance in a slow, almost hypnotic rhythm.”70

The truth of all of these stories attempting to trace jazz back to some person named Jasbo was “extremely doubtful,” Alan P. Merriam and Fradley H. Garner wrote in a 1968 article for Ethnomusicology.71

Wherever the word came from, there’s also much debate about when exactly jazz became a word for music. That will be discussed in the next chapter.

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Footnotes

1 “Hit or Miss,” Chicago Daily News, September 7, 1917, 8.

2 “Crowded Houses Hear Patricola at Majestic,” Shreveport (LA) Journal, March 5, 1918, 8.

3 William Howland Kenney, Chicago Jazz: A Cultural History 1904-1930 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), xii.

4 Elijah Wald, How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ’n’ Roll: An Alternative History of American Popular Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 57.

5 Sandrachambers62 family tree, accessed July 3, 2023, Ancestry.com.

6 U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, Ancestry.com.

7 1915 Chicago city directory, 1478-1479, Fold3.com.

8 Gordon Seagrove, “Yeah! The Why of This ‘Service’ Item on Your Bill Is as Clear as Goulash,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 25, 1915, VIII, 8.

9 1915 Chicago city directory, 1478-1479, Fold3.com.

10 “Strikebreaker Explains Presence of Gun on Son,” Day Book, March 6, 1914, 30.

11 “Gordon K. Seagrove,” (New York) Daily News, September 5, 1963, 42.

12 Frank Heyes, “Following the Fleet,” Chicago Tribune, September 8, 1963, section 2, 5.

13 “Yacht Party in Peril Two Nights on Lake,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 21, 1915, 3.

14 Gordon Seagrove, “The Legion of Lost,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 19, 1915, part 5, 2.

15 Gordon Seagrove, “Chicago and Its City of Mysterious Death,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 3, 1915, part 7, 1.

16 Gordon Seagrove, “Girls, Here’s How He Grows That Lov-a-ly Pompadour,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 4, 1915, VII, 8.

17 Gordon Seagrove, “‘Eyes Are Bloo,’ I Love You,’ Ad Nauseam,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 10, 1915, VII, 4.

18 Gordon Seagrove, “Object Matrimony,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 16, 1916.

19 Gordon Seagrove, “The Addled Ad Man,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 24, 1910, 15.

20 Gordon Seagrove, “There’s No Working with Orville; He’s Got the Vaudeville Bug,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 23, 1910, Worker’s Magazine, 8.

21 “Orville, the Boy Bookkeep: He Tires of Frivolity of Life,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 6, 1910, Worker’s Magazine, 10.

22 Gordon Seagrove, “Blues Is Jazz and Jazz Is Blues,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 11, 1915, VIII, 8.

23 Oxford English Dictionary, online version, March 2023.

24 “Ben’s New Jazz Curve,” Los Angeles Times, April 2, 1912, III, 2.

25 “Ben Henderson,” Baseball Reference, accessed June 30, 2023, https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=hender003jam; Henderson Family Tree, accessed June 30, 2023, Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/165314651/person/312147696140/facts?_phsrc=ArG1727&_phstart=successSource

26 “Chimmie’s Column,” Oregon Daily Journal, August 8, 1911, 12.

27 “Benny Henderson Gets Suspension,” Oregon Daily Journal, May 5, 1912, part 4, 9.

28 Baseball Reference.

29 “Benny Henderson Is in San Francisco,” Eugene (OR) Guard, July 8, 1911, 7.

30 “Oaks in the South to Battle With Hen Berry’s Crew,” Oakland Tribune, July 4, 1911, 14.

31 “Benny Henderson Under Suspension,” Eugene (OR) Guard, October 19, 1911, 1.

32 “Odd Happenings in the World of Sport,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 24, 1911, 47.

33 “McCredie Hard up for Good Pitchers,” Vancouver Daily World, May 2, 1912, 14.

34 “Ben’s New Jazz Curve,” Los Angeles Times, April 2, 1912, III, 2.

35 R.A. Wynne, “M’Credie Put Them Through,” Los Angeles Times, April 2, 1912, III, 2.

36 Owen R. Bird, “Around the Bags,” Los Angeles Times, April 3, 1912, III, 3.

37 “Angels Win Opening Game of the Season,” Los Angeles Times, April 3, 1912, III, 1, 3.

38 “Benny Henderson Gets Suspension,” Oregon Daily Journal, May 5, 1912, part 4, 9.

39 “McCredie Hard up for Good Pitchers,” Vancouver Daily World, May 2, 1912, 14.

40 “Henderson Suspended; Will Not Come South,” Pomona (CA) Morning Times, May 8, 1912, 2.

41 “Klawitter Is Too Strong,” Los Angeles Times, June 9, 1912, 8.

42 Baseball Reference.

43 “Scoop” Gleeson, “M’Carl Performs Like Youngster Who Will Do,” San Francisco Bulletin, March 3, 1913. Reproduced in Dick Holbrook, “Our Word JAZZ,” Storyville 50 (December 1973), 50, https://nationaljazzarchive.org.uk/explore/journals/storyville/storyville-050/1267315.

44 Languagehat, “Jazz,” June 8, 2009, https://languagehat.com/jazz/; Wikipedia, accessed July 8, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twin_Peaks_(San_Francisco), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twin_Peaks_Tunnel.

45 J.E. Lighter, ed., Random House Dictionary of American Slang, Volume II, H–O (New York: Random House, 1997), 258; Ben Zimmer, “How Baseball Gave Us ’Jazz,’” Boston Globe, March 25, 2012.

46 “Dance Grows in ‘Dry’ Cafes,” San Francisco Examiner, October 12, 1919, W16; Thomas W. Baily, “Band Leader Says Jazz Is Public Demand,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 9, 1919, 7.

47 Holbrook, “Our Word JAZZ,” 53.

48 Ernest J. Hopkins, “In Praise of ‘Jazz,’ a Futurist Word Which Has Just Joined the Language,” San Francisco Bulletin, April 5, 1913. Reproduced in Holbrook, “Our Word JAZZ,” 54-55.

49 Wald, How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ’n’ Roll, 56.

50 Holbrook, “Our Word JAZZ,” 52.

51 Alan P. Merriam and Fradley H. Garner, “Jazz—The Word,” Ethnomusicology 12, no. 3 (1968): 380-383. https://doi.org/10.2307/850032; “Chords and Discords: Few by Charlie Leedy,” Rock Island (IL) Argus, April 30, 1917, 7. Reprint from Youngstown (OH) Telegram.

52 Oxford English Dictionary, online version, March 2022; J.G. Holland, Miss Gilbert’s Career: An American Story (New York: C. Scribner, 1860), 350, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t5s757409?urlappend=%3Bseq=364.

53 Oxford English Dictionary, online version, March 2022.

54 J.E. Lighter, ed., Random House Dictionary of American Slang, Volume II, H–O (New York: Random House, 1997), 258.

55 Holbrook, “Our Word JAZZ,” 48.

56 Holbrook, “Our Word JAZZ,” 48-49.

57 “Bert Swor,” Wikipedia, accessed June 16, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bert_Swor.

58 Eugene L. Connelly, “Origin and Character of ‘Jazzband,’” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 20, 1917, section 6, 2.

59 Merriam and Garner, “Jazz—The Word,” 380. Cited source: Paul Whiteman, “What Is Jazz Doing to American Music?” Etude 42 (August 1924), 523.

60 Oxford English Dictionary, online version, December 2022.

61 Merriam and Garner, “Jazz—The Word,” 373-379.

62 “Roger A. Graham,” Wikipedia, accessed July 20, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_A._Graham.

63 Merriam and Garner, “Jazz—The Word,” 373-374. Cited source: “Jazz Origin Again Discovered,” Music Trade Review 68 (June 14, 1919), 32.

64 United Press, “Noted Composer Dies—Alone and Unsung,” Nashville Banner, October 26, 1938, 1.

65 “Fletcher Henderson,” Wikipedia, accessed July 26, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fletcher_Henderson.

66 “Jazzbo Brown From Memphis Town,” SecondHandSongs, accessed July 15, 2023, https://secondhandsongs.com/work/165557/all.

67 “Jazzbo Brown From Memphis Town,” Genius.com, accessed July 26, 2023, https://genius.com/Bessie-smith-jazzbo-brown-from-memphis-town-lyrics.

68 “DuBose Heyward,” Wikipedia, accessed July 26, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DuBose_Heyward.

69 “Jazbo Brown,” Wikipedia, accessed July 15, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jazbo_Brown; https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001028660.

70 “Porgy and Bess Libretto,” Opera Arias, accessed July 26, 2023, https://www.opera-arias.com/gershwin/porgy-and-bess/libretto/.

71 Merriam and Garner, “Jazz—The Word,” 379.