Chapter 6 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

In September 1910, Tom Chamales began leasing the saloon formerly known as Pop Morse’s roadhouse.1 Less than four years later, he would build the larger Green Mill Gardens at the same spot, the northwest corner of Lawrence Avenue and Broadway. But in the meantime, his saloon became a flashpoint for controversy in the surrounding neighborhood.

This was in the heart of the district that became known as Uptown, but in the years just after 1910, newspaper stories usually referred to it as the North Shore. Today, “North Shore” means the suburbs along Lake Michigan to the north of the city. But in the early 20th century, it was often used to describe a stretch of the city’s North Side.

People in Chicago’s North Shore area began raising an alarm about the goings-on at Tom Chamales’s saloon and beer garden in June 1911, nine months after he’d taken over the establishment. The protests were part of a larger outcry over crime and disorder in the upscale neighborhood. In addition to complaining about the way Chamales ran his bar, neighbors were upset about the crowds at privately owned beaches along the lakeshore just north of Montrose Avenue, along the east side of Clarendon Avenue.

Where the beaches were

At the time, the shoreline was farther west than it is today. As shown in this annotated portion of a U.S. Geological Survey map from 1901, Clarendon was the north-south street closest to the lakefront. The edge of the water was roughly where Marine Drive and DuSable Lake Shore Drive are now.

In the summer of 1911, controversies over the Chamales saloon and the beaches became tangled together amid a general uproar about an invasion of “rowdies” in the North Shore neighborhood.

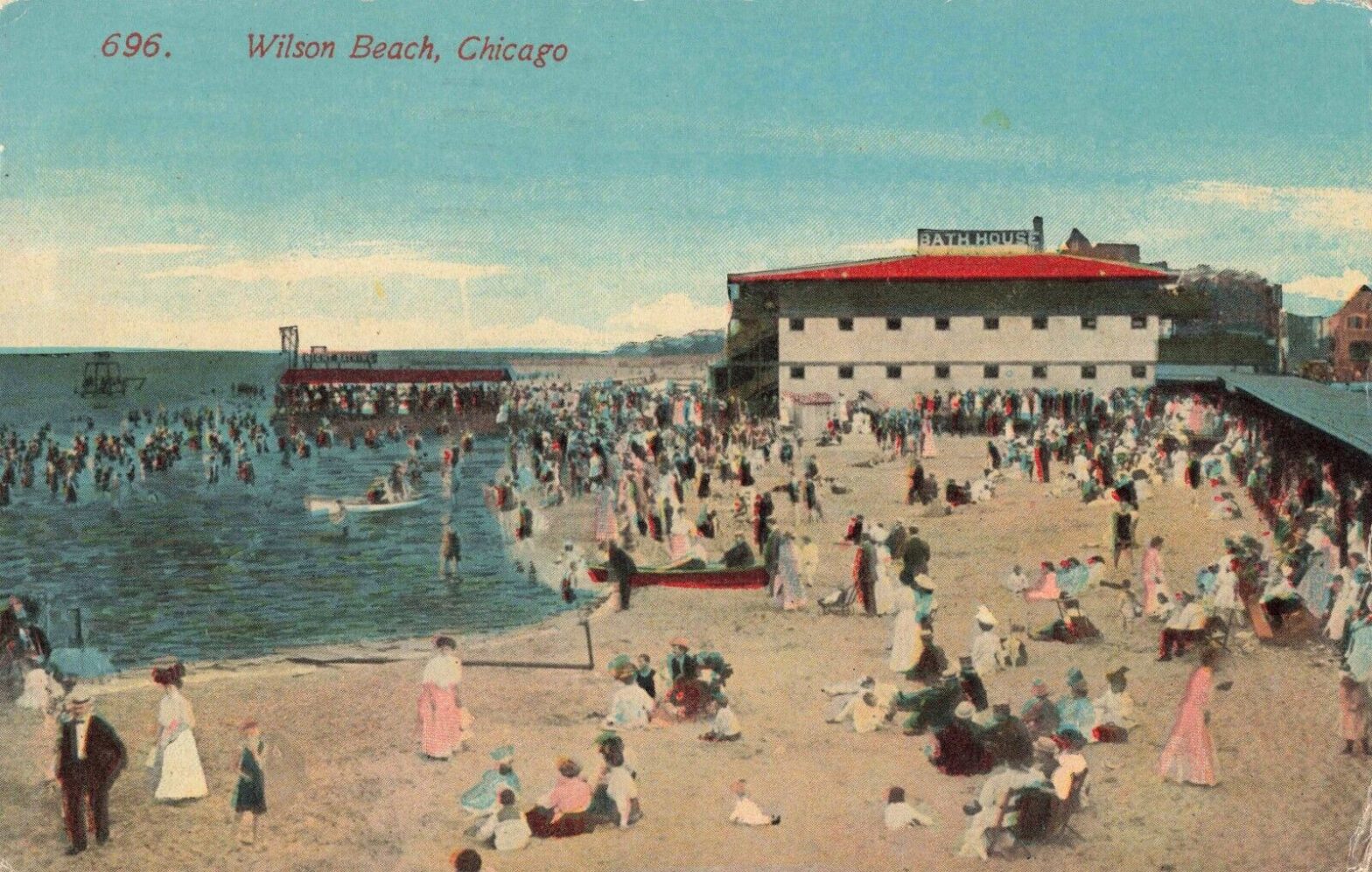

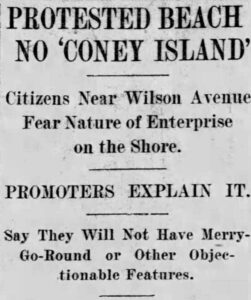

The beaches had been controversial since they opened. In 1908, when the Wilson Avenue Bathing Beach and Amusement Company began constructing a large building with changing rooms for swimmers, neighbors feared that the place was going to be “a noisy amusement park” similar to New York’s Coney Island.2

“I was afraid of the class of people who will come out to these beaches,” said one resident, C.H. Ravell. “It will not be safe for our wives to walk out alone.”

And neighbors predicted that their property values would drop—presumably because people wouldn’t want to buy homes next to a raucous beach.3 (As it turned out, property values in the neighborhood would actually jump, quadrupling between 1909 and 1923.4)

Neighbors urged city officials not to issue licenses for the companies to operate beaches, but the beaches managed to open for business, while judges heard arguments about their legality.5 City officials argued in court that the beaches should be shut down, because they were attracting “noisy persons, many of whom are immoral in character, profane of language, and nuisances in other ways.”6

This was at a time when the city had recently opened a few municipal beaches, but for many Chicagoans, the closest spots to swimming or bathing in the lake were privately operated beaches that charged admission.7

Despite the outcry from NIMBYs, some North Shore residents welcomed the beaches. In 1908, the Wilson Avenue Bathing Beach Company presented a petition to mayor Fred Busse, signed by 4,670 residents of the 25th Ward who agreed that the beach would be a “boon” rather than a “menace.”8

On an especially hot day in August 1909, when the temperature hit 93, the Tribune reported that more than 5,000 people went to each of the neighborhood’s four beaches.9

The Chicago Swimming Club held water polo matches at the Wilson Avenue Beach.10 In an annual competition, swimmers jumped into the water at the Lake View Crib, which was located offshore, and raced two miles to the Wilson Avenue Beach.11 (That water-intake crib was demolished in 1924, but the Wilson Avenue Crib is still visible out in the lake.12)

An early version of a “polar plunge” took place at the Wilson Avenue Beach in January 1909, when Julius Singer, a visitor from Sitka, Alaska, dared three men to join him diving into the lake’s icy waters. W.F. McCarthy and Anton Slawek of Chicago and J.H. Lewis of Rockford took him up on the dare, jumping into the lake at 4 a.m.13

Newspapers also reported on several drownings at the beach, as well as rescues that saved people from drowning.14 This was at a time when drownings were far more common than today. In 1912, 128 people died of accidental drowning in Chicago, although the city’s statistics didn’t say how many of those drowned in the lake.15 In comparison, 45 people drowned throughout Lake Michigan in 2022, including places outside Chicago.16

(The writing on the picture above was a message by the person who sent this postcard. Like the other two color images of Wilson Avenue Bathing Beach included in this blog post, this picture was found on eBay.)

Within a few years, the Wilson Avenue Bathing Beach was attracting as many as 22,000 daily visitors on the summer’s busiest days.17

‘Throngs of ruffians’

Complaints in the North Shore neighborhood grew louder in 1911, when residents said the beaches were attracting “throngs of ruffians.”

These “undesirables” were also allegedly hanging out at Tom Chamales’s saloon, as well as a bar operated by two of his brothers at 6330 North Clark Street and the Arcadia, 18 a dance hall that opened in 1910 at 4450 North Evanston Avenue (now Broadway), adjacent to workshops for the elevated train system.19

The neighborhood also had a vaudeville house, the Wilson Avenue Theater, at 1050 West Wilson Avenue, which had opened for business in 1909. (That building later became a bank, and there are now plans for it to become to new location of the Double Door rock venue.)20

Residents complained that Tom Chamales’s saloon persistently stayed open after the legal closing time of 1 a.m.21

The Reverend Henry Hepburn, pastor of the Buena Memorial Presbyterian Church, said that one of the neighborhood’s saloons “admitted young girls within its doors at all hours of the day and night,” the Tribune reported, without specifying which saloon. The newspaper also noted: “Witnesses have seen women come and go from the saloons as late as 4 o’clock in the morning.”22

Residents referred to the people entering their neighborhood as “the criminal element.”23 Some of these comments seemed to show prejudice toward people of lower classes.

For example, the Tribune described how ministers in this wealthy neighborhood preached against “the invasion … by rowdies from less favored neighborhoods in the city.”

John V. Fox, who’d been doing business in the neighborhood for 10 years, said “he had never seen such rough looking specimens of men and women there as this summer.”24

Although the beach did attract visitors from other parts of Chicago, it’s also possible that some of these supposed interlopers actually lived nearby. The population was growing in this part of the North Side, thanks to the opening of the elevated train line from downtown Chicago to Wilson Avenue in 1900. And as the neighborhood boomed, apartment buildings were constructed, creating residences for people who might not be able to afford larger homes.25

Whenever the beaches were closed for the season, the neighborhood “is as orderly as a country village,” said S. Mason Meek, a wealthy property owner who was the North Shore Improvement Association’s president. “As soon as the beaches open, there is a number of bums, vagrants, and loafers who make the beach their home. They are like rodents.”

Meek urged the police to arrest anyone who looked like they came from a different neighborhood, which he thought would be obvious.

“It is not hard to detect which of these men do not belong around this neighborhood. They show on their faces that they are from some other part of the city. Why do the police allow them to stay around here?”26

When the Reverend Ingram E. Bill, of the North Shore Baptist Church, spoke about these visitors, he made them sound almost demonic.

“How long will the trail of the beast leave its slime upon beautiful Sheridan Park?” he asked. “The spoilers have dared to lay their unhallowed hands upon the community. The thug and the assassin are rampant, and the lawless have assailed our homes.”27

Outcry over prostitution and licentiousness

This controversy in the North Shore neighborhood erupted in the midst of a citywide and national outcry about prostitution. On April 5, 1911, the Chicago Vice Commission had published The Social Evil in Chicago, a nearly 400-page book that quickly became a bestseller in the city. The blockbuster report concluded that Chicago had at least 1,020 brothels and some 5,000 women working full-time as prostitutes.

The book heightened the pressure on city officials to shut down the Levee district around 22nd Street on Chicago’s South Side, where police had allowed brothels to operate for years. At the same time, talk about shutting down the Levee sparked fears that prostitutes would simply move into other neighborhoods.28

The above photo comes from the 1910 book Fighting the Traffic in Young Girls, or, War on the White Slave Trade, by one of Chicago’s leading anti-prostitution crusaders, Ernest A. Bell. The photo’s caption said: “ENTRANCE TOO A HOUSE OF SHAME. The picture shows the entrance to a notorious vice resort, with three of the wanton women at the door. A missionary who was making the rounds, is standing close by. It is when these girls are ill or in trouble that they are most easily brought to their senses.”

At the time, some Americans were disturbed by changes in sexual morality.

“While the divorce rate rose the birth rate declined, seemingly indicative of growing self-indulgence,” Peggy Moore Barron wrote in a 1977 thesis on the topic. “An increase in wealth and leisure time created a demand for pleasurable outlets such as bowling alleys, dance halls and pool parlors. Most upsetting of all to some, the motion picture with its ‘potentially sinful’ theaters and its sexually provocative themes, threatened to undermine the morals of young Americans.”

These concerns heightened the national alarm about prostitution and sex trafficking.29

But the “social evil” was not just prostitution or “female slavery,” according to the Reverend William Burgess, who lived in suburban Des Plaines.30

In his book The World’s Social Evil, Burgess said the evils plaguing modern society also included “licentiousness.” Burgess saw “a prevailing sex licentiousness” that was “rooted in the common life of the people.”

According to Burgess, the bad influences causing people to become more promiscuous included “the ribald song, the unseemly jest, the story with double meaning, the vicious novel, the gross theatrical show, the indecent picture and postcard,” and “the newspaper report detailing divorce court proceedings.”31

Amid all of the furor about vice in Chicago, ministers and other community leaders in the North Shore neighborhood condemned the licentious behavior they said they were witnessing. At times, they may have been hinting about prostitution. But they were also concerned about young people flirting, dancing suggestively, and having sex. At least, that’s what they seemed to be concerned about. It can be hard to tell precisely what they meant, given the era’s guarded language and euphemisms.

For instance, what was Reverend James S. Ainslee, pastor of the North Shore Congregational Church, talking about when he described an encounter outside Tom Chamales’s saloon?

“The other night on my way home I passed Chamales’s resort at Evanston and Lawrence Avenues,” he said, “and two women came out of a side door and exercised all their cleverness in the art of smiling in an effort to attract my attention. Conditions in the neighborhood are positively shameful.”32

Ainslee may have been outraged by the very fact that these women were in a bar at nighttime. It’s conceivable they were simply enjoying a night out on the town—something of a novel concept in 1911. That probably would have been shocking enough for the minister to express his outrage. Or was he appalled that such women would use “the art of smiling” to get his attention? Were they just being friendly or flirtatious? Or was he insinuating that they were prostitutes?

Beware of B-girls

Some of the women in the neighborhood’s saloons seemed to be what would become known later as “B-girls.” (That slang term apparently didn’t become commonplace until the 1930s.33) “Her job is to mingle with the male patrons and induce them to buy her drinks,” Cook County sheriff’s official Arthur J. Bilek and a former Cook County prosecutor, Alan S. Ganz, explained in a 1965 article about B-girls. “The drinks that are purchased by a male patron for her customarily consist of tea, colored water, or some mildly alcoholic beverage. For each drink she procures from a male patron, the B-girl is paid a commission. In the course of her sales campaign, she sometimes commits acts of lewdness upon a male patron to encourage his purchase of drinks for her.”34

There’s some mystery about why they were called B-girls. Some people believe the “B” stood for “bar,” “beer,” or “bee,” as in “busy bee” or “putting the bee on.” One researcher concluded that it was actually an abbreviation for “beading oil,” a substance used to produce bubbles in watered-down whiskey, making the drink look like normal booze.35

The 1911 book The Social Evil in Chicago described some of these women at work in the Levee district: “The girls are very aggressive, and do not wait for an invitation, but sit down at the tables, and … order a round of drinks that costs no less than 40 cents. The mixed drinks brought to the prostitutes are counterfeit. For instance the girl orders a ‘B’ ginger ale highball. This is colored water made in imitation of this drink. The cost is probably less than a cent, but the victim pays 25 or 50 cents for it.”36

According to Bilek and Ganz, B-girls included entertainers (such as striptease dancers) who mingled with customers after a performance. Others were waitresses and female bartenders, or women who were hired by bars to “sit or stand around the bar and strike up conversations with male patrons.”37 (Chicago outlawed bars from employing B-girls and most female bartenders in 1952,38 but a federal judge ruled in 1970 that the ordinance was unconstitutional.39)

Orgies and the ‘Aquatic Grizzly Bear’

The Reverend Ainslee also described nocturnal bacchanalias on the North Shore neighborhood’s beaches.

“Things that take place on these beaches after dark and which people who live in the vicinity cannot help seeing are beyond belief,” he said. “Many of those who participate in these orgies are boys and girls of tender age.” (Saying they were “of tender age” doesn’t necessarily mean these were children. Then, as now, it was common to describe young men and women as “boys” and “girls.”)40

Meek told a similar story. After dark, he said, “There are some revels on the beach that are disgraceful.”41 A headline in the Inter Ocean declared: “Prominent Men Describe Some of the Orgies as Too Vile for Print—Three Girls Parade Sands in Nude.” But the article below the headline didn’t say anything about nude girls.42

(At the time, Chicago required swimmers to be “clothed in a suitable bathing dress.”43 That ordinance was vague, but police generally required girls and women to wear bathing suits that covered nearly their entire bodies, including skirts. One woman was arrested for removing her skirt and exposing her bloomers.44)

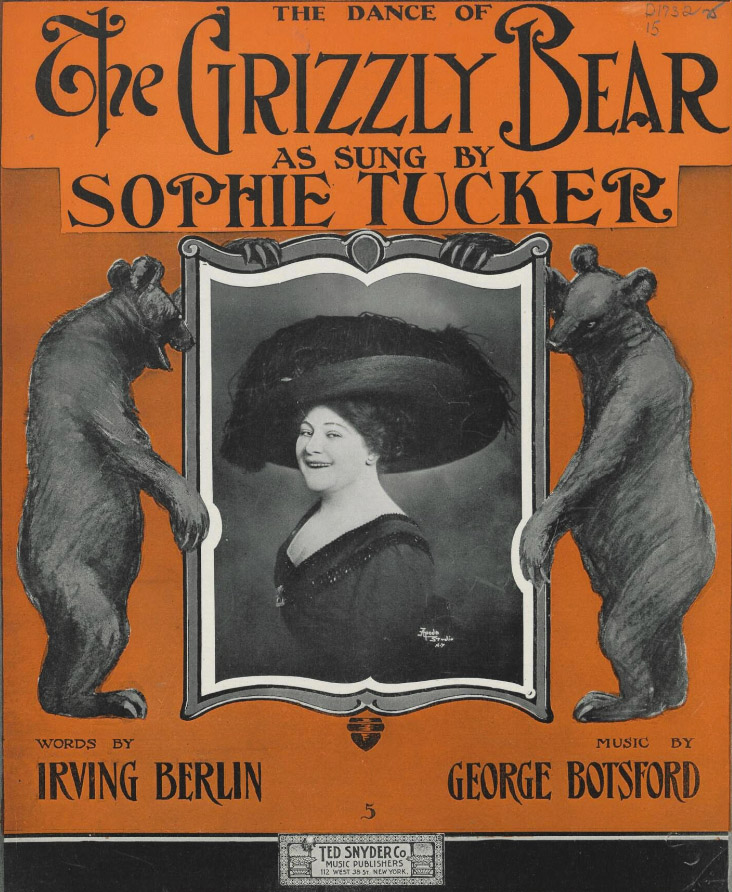

Neighbors were upset by beachgoers performing “The Grizzly Bear,” a sexually suggestive dance.

The dance had been popularized by a 1910 song with lyrics by Irving Berlin45: “Hug up close to your baby, Throw your shoulders t’ward the ceiling, Lawdy, Lawdy, what a feelin’, Something nice is gwine to happy, hug up close to your baby … You and me is two, I’ll make it one when we get through, Doin’ the grizzly Bear.”46

Here’s a 1913 film of the dance:

The dance and song also made a rather tame appearance in the 1943 movie Hello, Frisco, Hello:

When the craze hit Chicago in early 1911, the Tribune described people dancing “The Grizzly Bear” at a secluded venue where a “negro orchestra” was playing “ragtime, but with an oriental savor.” The women on the dance floor had “a languorous intoxication that caused them to droop limply, with half crossed eyes, as they swayed from side to side in the safety clutch of their partners.”47

Writing for the Tribune, Gene Morgan described this “primeval” dance as “a rhythmic echo from an age when the male sex dominated with what some femmes of this day have been moved to term a perfectly lovely brute tyranny.”48

This was too much for certain Chicagoans to tolerate. So, the Chicago Police Department banned “The Grizzly Bear” dance. But one club owner remarked, “I don’t care what anyone says—there ain’t no law against ‘The Grizzly Bear.’”49

Now, young people were performing the same dance moves as they stood in the water just offshore at the Wilson Avenue Bathing Beach.

The Tribune described these people as “transplanted habitues” of the “tenderloin dance halls” where “The Grizzly Bear” had been performed the previous winter, before it was banned by police. The newspaper seemed to be insinuating that “habitues” who’d hung out in the South Side’s notorious Levee vice district were now congregating at Wilson Avenue Bathing Beach.

“It is impossible to describe the ‘Aquatic Grizzly Bear,’ except to say that the dance which came under police displeasure is tame and respectable compared to the exhibition given by the scantily clad bathers,” the Tribune reported. Local churchgoers were dismayed that the beach’s guards joined in with bystanders to applaud the dance rather than stopping it.50

One neighborhood group, the East Sheridan Park Protective Association, took photos of the “aquatic grizzly bear dance” as evidence of debauchery.

“We have witnesses who can testify that policemen stood on the shore and watched this indecent proceeding without making the least effort to stop it or even to discourage it,” said the association’s president, Amos W. Marston.51

“Most of the people who flock to Wilson beach now don’t go there to bathe, but to prance around and make life miserable for the decent people who come down there,” said W.W. Baird, who owned real estate in the neighborhood.52

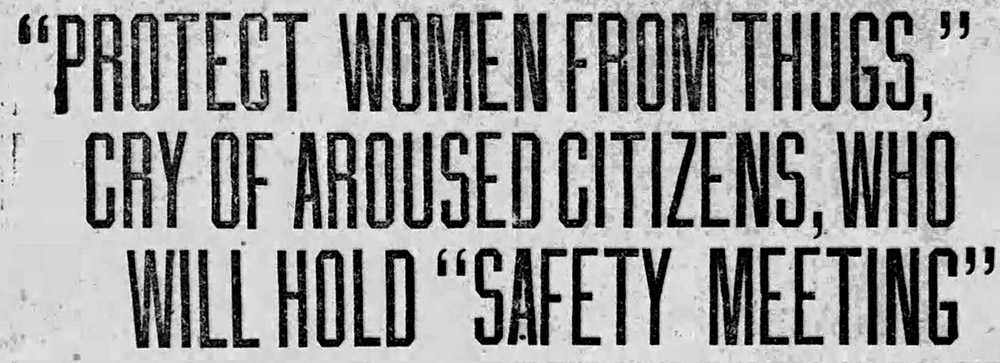

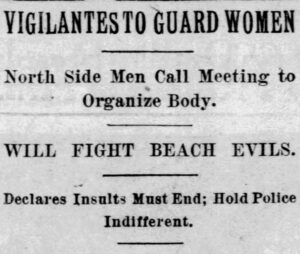

Violence and vigilantes

Beachgoers and saloon patrons were also accused of insulting, harassing, and assaulting local residents. “Two well-dressed young men” attacked a 25-year-old woman—who was married, with a four-year-old daughter—after midnight as she was walking to her home near Leland Avenue and Evanston Avenue (now Broadway).

“At the alley they overtook me,” she told the Chicago Examiner. “One threw his arm around my neck from the back and drew me backwards, while the other stuff a paper saturated with chloroform into my mouth. I made a vain effort to free myself and told them if they wanted my personal property to take it. The only thing I recall having head them say was: ‘Shut up.’”

The Examiner did not explicitly call this a sexual assault, but the victim said that the men tore off her clothing. “Several times before I became unconscious, I was struck in the face,” the victim said. “My clothing was torn from my body. My limbs are bruised and burned with chloroform where they poured it on me after I had been battered and bruised. The doctor tells me that I am burned internally from the chloroform and that it may be a long time before I can recover.”

The Examiner said that the woman “was in a condition when an attack or a scare is most injurious and her experience may result seriously.” Was it hinting that she was pregnant?

The woman also remarked: “Police protection is lacking in a city when a woman cannot walk along the streets on her way to her home without being attacked and brutally beaten by ruffians, who have no respect for motherhood or life itself. The attack upon me is the most outrageous thing that could happen in a civilized country.” 53

In a sermon at the North Shore Baptist Church shortly after the attack, the Reverend Bill condemned “the violent disregard of the sacred spirit of womanhood which the chivalry of all ages has persistently protected.” 54

The Chicago Daily News reported that the woman was “dragged into a dark alley, chloroformed, beaten and robbed, and it was nearly four hours later when she was discovered by a passing milkman.”55

The identity of her assailants was unknown, but Meek sounded certain when he said, “I attribute the attacks on this woman Thursday night to the bathing beaches.”

Meek also said, “I understand there have been four children attacked in the past three months.” According to the Examiner, “many outrages, particularly against small children,” had been reported over the previous three months, including “brutal attacks on women and small children.”

The newspapers and neighbors were vague, however, about the exact nature of these attacks. “There is a tough element brought to this locality by the beach who are ever waiting to attack a woman or child, much as a chicken hawk attacks its prey,” the Reverend Ainslee said.56

In his sermon, the Reverend Bill blamed the neighborhood’s crime wave on “the crowding of large numbers of people into a circumscribed space, the almost unrestrained spirit of disorder, the night carousing of the visitors who come here by day to the bathing beaches and stay till the saloons close.”57

During the same week when the woman was attacked, a melee broke out in the Chamales Bros. saloon on Clark Street near Devon Avenue. Three or four bricklayers got into an argument as they were drinking. Two police officers who were passing by the saloon, Thomas McMahon and Edward Dean, tried to break up the fight. The bricklayers turned against the officers, beating them severely. McMahon and Dean pulled out their revolvers, shooting at the men and wounding two of them.58

“The influx of low saloons in Ravenswood and the consequent disorder can be traced directly to the influence of the north shore bathing beaches,” said a Mr. Ternes, who was the Ravenswood Improvement Association’s secretary.

“The shooting in the Chamales resort is an example of what we may expect in the future unless a change is brought about. … The police may be doing their best to prevent disorder, but they are sadly handicapped by conditions. Ruffians of the type of saloon loafer are hard to deal with, as was shown in the affair of Saturday night in Chamales’s place. As matters stand, the streets after nightfall are unsafe for the wives and daughters of residents. Unless the mayor and police can do something to guarantee safety, we must face the necessity of forming a vigilance committee.”59

Some reports about the incident incorrectly said it happened at Tom Chamales’s saloon, rather than the one owned by his brothers.

“The Clark Street place is owned by George and James Chamales,” Tom said. “They have nothing to do with my place, and I have nothing to do with theirs, financially, managerially or otherwise.”

In the face of criticism, Tom Chamales insisted that his saloon “caters to the respectable element of the north shore,” according to the Examiner.60

Giving residents a chance to speak out, the Reverend Ainslee hosted what he called a “mass meeting of indignation” at the North Shore Congregational Church. “The people of this neighborhood are entitled to police protection and they intend to get it. We will go to the limit on this thing. This last attack is a disgrace,” he said, referring to the woman who was chloroformed and beaten. “The people are up in arms.”61

Like other residents, Ainslee was also worried about property values. “I am a property holder myself, and I know that values of real estate have been kept back because of the invasion of rowdies,” he said. “I know of several families who have moved out because they could not stand the beach rowdies.” 62

More than a thousand people crowded into the North Shore Congregational Church, at the southwest corner of Wilson Avenue and Sheridan Road. (It’s now the Uptown Baptist Church,63 easily recognized by a sign on the roof declaring “CHRIST DIED FOR OUR SINS.”)

Men and women in the crowd gasped when one of the 25th Ward’s aldermen, Charles R. Thomson, said that every flat building in the neighborhood included “a questionable apartment.”

Thomson was echoing a finding reported in The Social Evil in Chicago. That book described a female investigator visiting real estate agents around the city, saying she wanted to rent space for a “sporting house.” Forty-four of 65 agents were willing to help her secure a place for prostitution.

One of these agents told her that he “knew of a woman on Wilson Avenue who had a place and a list of married women she called in when necessary.”64

At the church meeting, some people criticized the police for providing insufficient protection. The Reverend Hepburn questioned how it was possible that the police could be unaware of the gambling taking place in the neighborhood.

And Amos W. Marston, president of the East Sheridan Park Protective Association, remarked: “I have evidence to show that no decent woman is safe on the streets in this neighborhood after 7 o’clock at night.”

The gathered citizens demanded that the city should revoke Chamales’s liquor license, or at least conduct “special surveillance” of his saloon. They also urged Mayor Carter H. Harrison to revoke the licenses of the Wilson Avenue Bathing Beach, the North Shore Bathing Beach, and the Clarendon Bathing Beach. Hearing these proposals, the audience “stamped and shouted its approval,” the Examiner reported.65

Harrison, who’d served as mayor from 1897 to 1905, had just returned to the office in April 1911. His father, also named Carter H. Harrison, had been mayor from 1879 to 1887 and in 1893, until he was assassinated. They were both known for running Chicago as a “wide open city,” with a lax regulation of saloons.

As the North Shore neighborhood’s churches helped organize a campaign against crime, they seemed to face threats. “Thugs Try to Burn Churches Fighting to Clean Up Beaches,” the Inter Ocean declared in a headline.66 While a service was in progress at the Buena Memorial Presbyterian Church at Sheridan Road and Evanston Avenue, someone apparently tried to start a fire.67

It’s unknown who did this—or what their motive was—but one of the anti-crime movement’s leaders, S. Mason Meek, confidently asserted: “The attempt was undoubtedly made by these lawless resort keepers or their hirelings. A mass of cotton waste was set on fire in a room on the west side of the church while the collection was being taken, and a rough-looking man was seen running out of the room. If the fire had not been discovered just when it was, there might have been a panic and loss of life.”

A short time later on that Sunday, a “rough-looking man” was chased away from North Shore Congregational Church after people saw him trying to set fire.

“No one can doubt that these two attempts were made by the lawless element who wish to terrify us,” said Meek, who described a conspiracy against the neighborhood by “a band of outlaws.”

As he explained, “The men who own the bathing beaches and the disorderly saloons will stop at nothing to defeat the efforts of the law-abiding and respectable men of the neighborhood to form a law-and-order league.”68

The residents formed the Amalgamated North Shore Improvement and Protective Association.69

“I don’t advocate lynching, but I think it is time for the men who live in the neighborhood of the Wilson Avenue Bathing Beach to take radical action,” said one of the organizers,70 Joseph G. Tyssowski, a lawyer who lived on Leland Avenue.71

“I could take a hundred business men, and arm them with automatic revolvers, and clean out this whole district. Common intelligence and ordinary persistence in the pursuit of criminals would place the entire gang of thugs and rowdies, who have been creating disturbances up here, behind the bars within 24 hours.”72

Even after the Chicago police superintendent, John McWeeny, refused to issue permits for this association to carry pistols, Tyssowski said, “I believe we should go armed.”

But the Reverend H.B. Gwyn, rector of St. Simon’s Protestant Episcopal Church, countered: “I protest against any talk about arming ourselves with guns. It is not becoming the supporters of law and order to talk about using guns.” The group agreed to drop the idea of carrying guns.73

Responding to pleas from the neighborhood, Mayor Harrison told the police to monitor saloons such as Tom Chamales’s place.

“In regard to the disorderly saloons in the neighborhood, I will say that I do not intend to allow the disorderly element to invade that residence district while I am at the head of municipal affairs,” he said. “I am having the places watched, but evidently they know they are watched and are on their good behavior at present.”74

The police superintendent issued a set of orders that aimed to reduce crime in the neighborhood:

Every saloon that permits women and minors to frequent the place or otherwise violates the law and order will be closed.

Idlers on street corners will be forced to move on or will be arrested.

Parents who permit their daughters to wear short dresses and to frequent public places unescorted at late hours will liable to prosecution for contributing to juvenile delinquency,

Undesirables found within the dead line drawn by the North Shore Protective association will be ousted from the district.

Automobile scorching down Wilson avenue and Sheridan road will be stopped.

It’s unknown how strictly the police enforced these regulations. But Harrison also ordered the beaches to close at 9:30 p.m., which seemed to have “a good effect,” the Inter Ocean reported.75

A push for public beaches

The mayor and local residents said that the ultimate solution was for local government to acquire the privately owned beaches and turn them into public lands. In a resolution, the residents declared that “we are opposed heartily to any privately conducted bathing beaches in our midst.”76

One of them, W.W. Baird, remarked, “The city needs bathing beaches and plenty of them, but it should be under the management of the city and it should be closed up at the proper hours. There is no complaint against the beaches now run by the municipality.”77

Harrison agreed: “I think all public bathing beaches should be under the immediate jurisdiction of the city.”78

Two years earlier, architects Daniel H. Burnham and Edward H. Bennett had proposed a similar concept in their landmark 1909 report, Plan of Chicago.

Burnham and Bennett didn’t say anything specifically about beaches run as for-profit businesses, but they urged the city’s lakeshore to be used as parks and beaches.

“The Lake front by right belongs to the people,” they wrote. “ … Wherever possible, the outer shore should be a beach on which the waves may break; and the slopes leading down to the water should be quiet stretches of green, unvexed by the small irregular piers and the various kinds of projections which to-day give it an untidy appearance.”79

In July 1911, the city began efforts to acquire the property north of Montrose Avenue and take it over as a municipal beach.80

Chamales stays active beyond the North Shore

Even after Tom Chamales began running Pop Morse’s roadhouse on the North Side, he stayed active for a while with other businesses in Chicago’s downtown and South Side.

In 1909, Chamales closed on a 99-year lease for land at the northwest corner of Cottage Grove Avenue and 63rd Street, where he planned to build a $60,000 theater for L.C. Quinn.81 That was the Trevett Theatre, which opened as a vaudeville house later that year. It’s unknown how long Chamales remained involved in this theater, which was later known as the Midway Hippodrome and the Midway Theatre. It was demolished in the 1960s.82

When the U.S. census was taken in April 1910, Tom Chamales was living with the family of his older brother John at 3624 Ellis Park, in the South Side’s Oakland neighborhood. Tom was 30 years old and single. John had married three years earlier: He was 39, with a wife and two toddler sons.83

It’s not clear exactly when Tom moved into a place of his own. No residence is listed for him in the city directories over the next few years, when he was simultaneously running the Savoy saloon downtown and Morse’s roadhouse on the North Side.

Chamales also became a part-owner of the Pekin Theater, at 27th and State Streets—in an entertainment district known as “The Stroll” in the city’s Black Belt. When Robert T. Motts founded the Pekin in 1904, it was said to be the country’s musical and vaudeville stock theater owned by an African American. But the Pekin’s popularity faded after Motts died in 1911.

In 1912, the Chicago Defender reported that Chamales owned the Pekin with Frank Haight. Their names surfaced because the Pekin planned to show a motion picture of the funeral for the wife of Jack Johnson, who was the reigning world champion heavyweight boxer at the time—and the first Black man who’d ever held that title.

Johnson’s wife, Etta, died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound on September 11, 1912. Ten days later, the Defender reported: “The proprietors of the Pekin theater, over-zealous to give ‘The Stroll’ something new, had arranged to give their patrons pictures of the funeral. Flaring signs announced the fact, but Mr. Johnson sought otherwise.”

Jack Johnson went before Judge William F. Dever in the Cook County Superior Court, receiving a temporary injunction against Chamales, Haight, and filmmaker C.R. Lundgren. Johnson then went to McWeeny, the police chief, who issued orders prohibiting the funeral movie from being shown.84

Meanwhile, Chamales continued operating a saloon on South Wabash Avenue—apparently the same one popularly known as the Savoy. From 1911 to 1913, Chicago city directories listed him as the proprietor of a saloon at 546 South Wabash. In 1913, his brother William was also listed as the owner of a café at 602 South Wabash. And in 1914, the address for Tom’s saloon was listed as 600 South Wabash. After that, it disappeared from the city directories.85

Tom Chamales’s North Side saloon advertised in the Tribune on New Year’s Eve 1911 under a new name—or rather, a new variation on an old name. It was now Morse’s Cafe & Garden. Chamales may have recognized the popularity of the saloon’s old identity as Pop Morse’s roadhouse. Maybe he was trying to improve the reputation of his saloon, in the aftermath of that summer’s neighborhood uproar. The ad did not mention the Chamales name, instead listing L.A. Jung as the manager, while boasting of “HIGH CLASS ENTERTAINMENT” and an “EXCELLENT KITCHEN.”

The musicians providing that entertainment on evenings as well as Sunday afternoons were Miss Isabella Patricola and her Orchestra, assisted by Miss Kaplan.86 Patricola—who was often billed as “Miss Patricola” or simply “Patricola”—would be the star attraction at the Chamales saloon several times over the next few years, continuing through the early days of Green Mill Gardens.

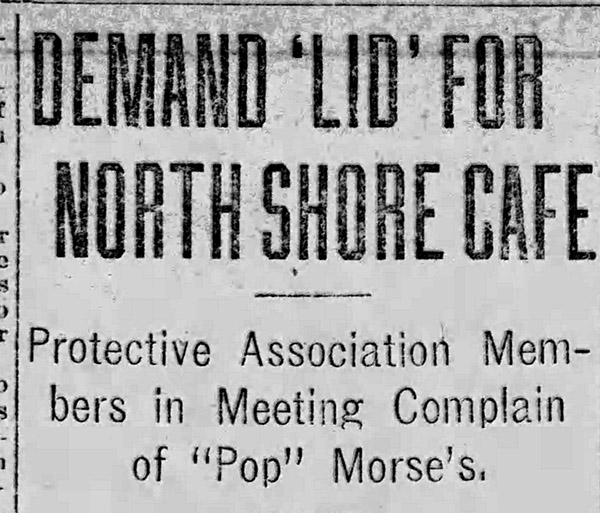

A new round of complaints

In February 1912, the Inter Ocean reported that North Shore residents had been complaining for months about Tom Chamales’s saloon (which the newspaper said was “known as ‘Morses’”). The residents blamed the saloon for turning their neighborhood into “a gathering place for notorious women.”

The newspaper also noted that Chamales and his brother James were “commonly reputed to have the financial backing of a South Side politician,” but it didn’t reveal the identity of this mysterious benefactor. Likely possibilities include the famously corrupt aldermen who reigned over the First Ward, “Bathhouse” John Coughlin and Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna.

Police officials asked Mayor Harrison to revoke James Chamales’s license for the saloon at 6331 North Clark Street, which he’d been running with their brother George. According to the police, a woman at the saloon was accepting a commission on drinks—in other words, working as a B-girl—when she robbed a customer of $55. Afterward, James had refused to give the woman’s address to police.

While waiting for the mayor’s decision on whether to revoke the license, police forbade the saloon from featuring any music or singing.87 The Chamales Bros. saloon on Clark Street disappeared from the city directory after 1912.88

Meanwhile, the citywide demands for a crackdown on prostitution finally reached a climax. In the fall of 1912, Cook County state’s attorney John Wayman and Mayor Harrison ordered mass arrests and prosecutions, effectively closing down the Levee as a segregated district for vice.89

Within a few months, North Shore residents again accused Tom Chamales of bringing the same sort of vice to their own neighborhood.

On January 16, 1913, the North Shore Improvement & Protective Association gathered for a meeting in the tea room in Marshall Field’s downtown department store. One member of the group, Winfield Dudley, said that Chamales’s saloon was attracting “disorderly women” to their neighborhood.

“Ever since Morse opened up his resort at the corner of Lawrence and Evanston Avenues there have been objectors to the place, but I never bothered about it until Chamales took it over,” Dudley said. “Pop ran a decent sort of cafe, but now there are nearly a hundred disorderly women living in the district and making the resort their headquarters. They pose as businesswomen, dressmakers, etc.

“I have indisputable evidence that four high school girls, living at home, make their headquarters there after school and add to their income by inducing chance acquaintances to buy liquor. I know, too, that many times they take their new friends to a flat that is not their own.”

The association’s members resolved to stop Chamales from employing women to sell liquor. They said they would force him to run his saloon “as a decent resort or not at all.”

They instructed lawyer Joseph Tyssowski (the same man who’d wanted to form a mob of gun-toting vigilantes in 1911) to “procure evidence against the disorderly flats that have sprung up in the neighborhood and to proceed against the owners of the buildings,” the Examiner reported.90

One of the aldermen for the 25th Ward, Henry D. Capitain, was skeptical about the group’s allegations—especially the story about high school girls frequenting the saloon.

“If they have any such evidence, why did they not bring it to me or Alderman Thomson?” he said. “Why do they make statements and take no action? I have written to Mr. Dudley today and asked for his evidence, and the moment I get it, I will go before the mayor and ask to have that saloon license revoked. If Dudley will not give me the evidence, I will investigate the place myself.”91

Business leaders and the pastors of five churches held a meeting at the North Shore Baptist Church to organize what the Inter Ocean called a “moral clean-up” and “a campaign of extermination.” The object was to push out “undesirable characters” who were hanging out at “questionable flats and cafes” in neighborhood. Much of the anger was directed at Tom Chamales, whose saloon was “regarded as the gathering place of most of the undesirables who have invaded the district.”

According to these complaints, the trouble started with the beaches. “With the opening of the bathing beaches in the vicinity certain quarters were colonized with persons who before had been seen only in other parts of the city,” the Inter Ocean explained. “Along with them came Chamales, and it is said he attracted others.”

Chamales “vigorously” denied that he had anything to do with apartments being used as “questionable resorts.” But neighbors said his local saloon was attracting many of the same customers who frequented his downtown bar, the Savoy.

Some North Shore business owners believed this was all part of a “colonization scheme” by “the ancient vice combine,” as the Inter Ocean called the cabal of brothel owners and politicians who’d controlled the South Side’s Levee prostitution district.

These North Shore leaders thought the “vice combine” was trying to colonize their neighborhood with prostitutes and disreputable characters. They suspected this was an effort to stir up public support for reopening the Levee. If enough people complained about prostitutes in their neighborhoods, that might persuade city officials to revive a segregated vice district on the South Side, where sex workers could operate far away from respectable residences. At least, that was how the Inter Ocean explained the theory.92

It’s unclear what effect, if any, this “extermination” campaign had. Tom Chamales continued operating his saloon. And on March 16, 1913, the Inter Ocean reported that he was planning a major change for the location. “The place of amusement is to be razed and a new garden completed by summer,” the newspaper said.93

How the beaches evolved

By the summer of 1913, the city’s beaches seemed to be more orderly, at least according to the Inter Ocean. “All the beaches in the city are orderly and well policed, and any girl or woman may feel safe from insult or improper advances from rowdies,” the newspaper reported. “The strictest rules are enforced for the protection of girl bathers, and good order is preserved at all times.”94

The city acquired land north of Montrose Avenue in 1913,95 and opened it in 1915 or 1916 as the Clarendon Municipal Beach, while the privately owned Wilson Avenue and North Shore beaches continued operating just north of it.96

In 1917, Tom Chamales hosted a meeting at Green Mill Gardens where the North Shore Beach Improvement Association was organized. By this time, Chamales was leading neighborhood business owners in a campaign to create more public beaches.

“Its purposes will be the proper policing and guarding of the existing beaches and the creation of funds for the extension of public beaches at the feet of nearly every street between the north end of Lincoln park and the south end of Evanston,” the Chicago Daily News reported.

The organization planned to hold a beach style show “for the purpose of arousing further interest in proper garb for bathing and encouraging artistic ideals in beach garments.”97

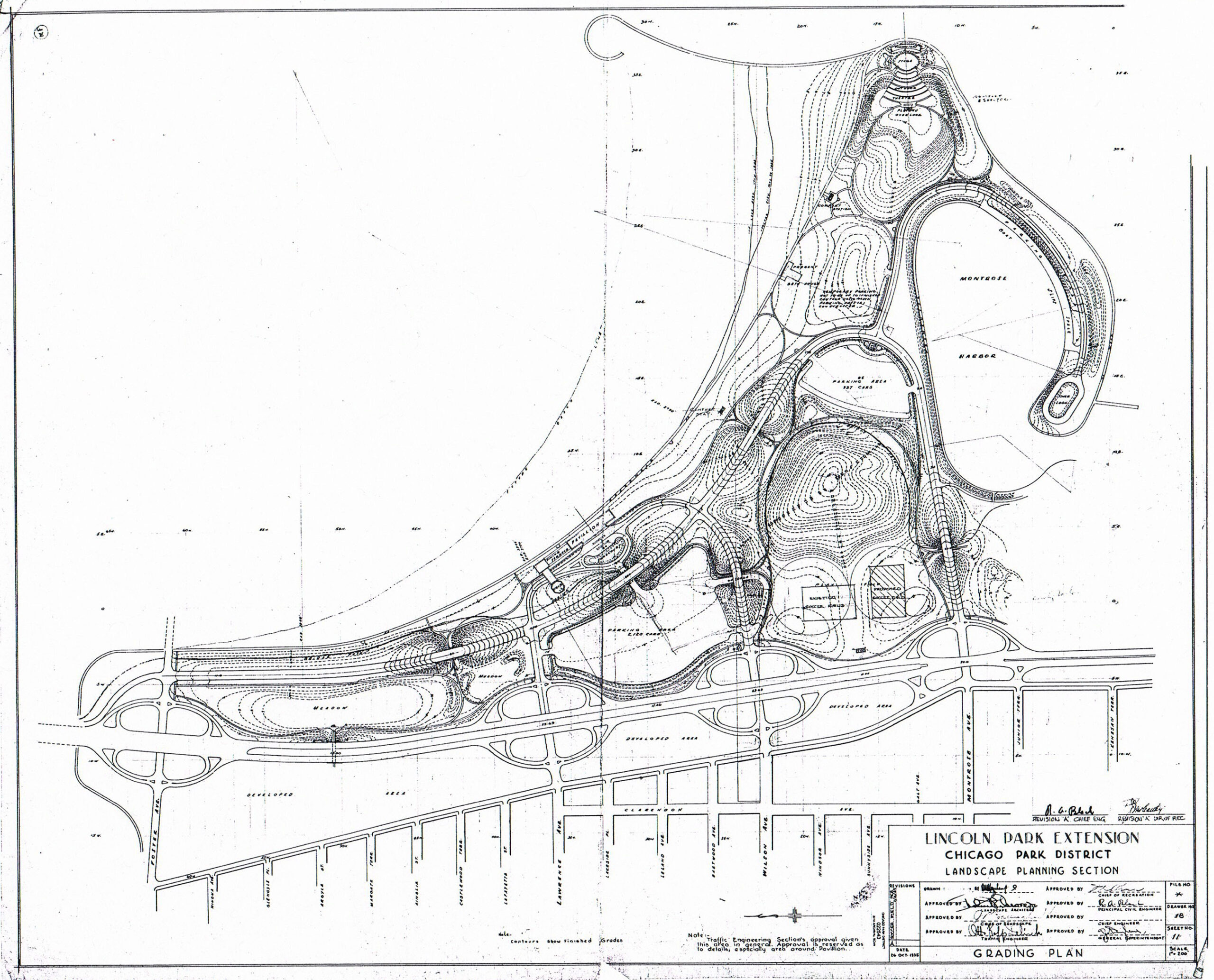

The lakeshore took on a new shape around 1930, as the Lincoln Park Commission extended the Outer Drive (now known as DuSable Lake Shore Drive) farther north—essentially building the road on top of the lake. Alongside the road, the commission also expanded Lincoln Park, adding land along the road’s eastern side.

At the end of 1931, the Tribune published this photo by the Chicago Aerial Survey Company, looking south from around Foster Avenue, showing how land was being added to the lakefront.98

In 1934—the same year when the Lincoln Park Commission became part of the new Chicago Park District99—a new beach opened on this manmade peninsula.100

The Tribune called it “probably the largest artificial bathing beach in the world,” noting that it was built with 1.8 million cubic yards of sand.101 Today, it’s known as Montrose Beach.

This 1935 landscaping plan for the beach and its peninsula is now part of the Chicago Park District Records: Drawings collection, which can be accessed on a computer in Special Collections at the Harold Washington Library Center.

Meanwhile, the land where Clarendon Municipal Beach, the Wilson Avenue Bathing Beach, and the other private beaches once existed became a park with a community center, playground, and athletic fields.102

This is how Clarendon Community Center Park appears today, as seen in an April 2023 aerial photo on Cook County’s website.

Imagine it as a beach, with the shoreline over on the right side of the photo where you now see Marine Drive and DuSable Lake Shore Drive. This is where “rowdies” once roused the neighborhood’s outrage.

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Footnotes

1 “‘Pop’ Morse Roadhouse Leased,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 22, 1910, p 13.

2 “Protested Beach No ‘Coney Island,’” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 29, 1908, 6.

3 “Fight Proposed Bath Beach,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 31, 1908, 10.

4 Harold Charles Hoffsommer, “The Development of Secondary Centers Within Metropolitan Cities: ‘The Wilson Avenue District,’ Chicago” (master’s thesis, Northwestern University, May 19, 1923), 32.

5 “City Must Wait for Press Agent,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 5, 1908, 11.

6 “Charges Against Wilson Beach,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 27, 1909, 20.

7 “Clarendon Community Center Park,” Chicago Park District, accessed April 20, 2023, https://www.chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks-facilities/clarendon-community-center-park.

8 “Will Seek Data for Subway,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 4, 1908, 8.

9 “Hottest Day of ’09 Routs Thousands,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 9, 1909, 1.

10 “Water Polo at Wilson Beach,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 9, 1909, 1.

11 “So Close the Judges Ponder,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 25, 1909, part 3, 2.

12 “Water Cribs in Chicago,” Wikipedia, accessed May 16, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water_cribs_in_Chicago.

13 “Man From Sitka, Alaska, Takes Chicagoans for Icy Swim in Lake,” Inter Ocean, January 29, 1909, 1.

14 “Actor Dies to Rescue Girl,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 6, 1910, 1.

15 John Dill Robertson, Report and Handbook of the Department of Health of the City of Chicago for the Years 1911 to 1918 Inclusive (Chicago: House of Severinghaus, 1919), 1240, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015038670595?urlappend=%3Bseq=1320%3Bownerid=13510798887113307-1326.

16 “Statistics,” Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project, accessed May 17, 2023, https://glsrp.org/statistics/.

17 “Come On In: The Water’s Fine,” Inter Ocean, June 8, 1913, magazine, 1.

18 “‘Protect Women From Thugs,’ Cry of Aroused Citizens, Who Will Hold ‘Safety Meeting,’” Chicago Examiner, June 11, 1911, 3; “Pastors Assail Beach Rowdies,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 12, 1911, 3.

19 Charles A. Sengstock, That Toddlin’ Town: Chicago’s White Dance Bands and Orchestras, 1900–1950 (Urbana: University of Illinois, 2004), 62.

20 Brian Wolf, “Wilson Avenue Theater,” Cinema Treasures, accessed May 16, 2023, http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/16568.

21 “Mayor May Revoke Permits to Beaches,” Inter Ocean, June 21, 1911, 12.

22 “Attack License of Wilson Beach,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 13, 1911, 3.

23 “North Shore Crime Blamed in Pulpits to Bathing Beaches,” Inter Ocean, June 12, 1911.

24 “Pastors Assail Beach Rowdies,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 12, 1911, 3.

25 Hoffsommer, 25.

26 “‘Protect Women From Thugs,’ Cry of Aroused Citizens, Who Will Hold ‘Safety Meeting,’” Chicago Examiner, June 11, 1911, 3.

27 “Pastors Assail Beach Rowdies.”

28 Karen Abbott, Sin in the Second City: Madams, Ministers, Playboys, and the Battle for America’s Soul (New York: Random House, 2007), 233; “The Social Evil in Chicago: Chicago History Classics,” Chicago Public Library, May 17, 2016, https://www.chipublib.org/blogs/post/the-social-evil-in-chicago-a-chicago-history-classic/.

29 Peggy Moore Barron, “The Mann Act: Progressives, Morality and the Courts, 1910-1937,” thesis, University of Houston, 1977, https://uh-ir.tdl.org/handle/10657/13386, 1-2.

30 “The Rev. William Burgess,” New York Times, August 1, 1922, 19.

31 William Burgess, The World’s Social Evil: A Historical Review and Study of the Problems Relating to the Subject (Chicago: Saul Brothers, 1914), 5, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo1.ark:/13960/t4hm5sp3k?urlappend=%3Bseq=15.

32 “Mayor May Revoke Permits to Beaches,” Inter Ocean, June 21, 1911, 12.

33 J.E. Lighter, ed. Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang, Volume 1: A–G (New York: Random House, 1994), 139-140.

34 Arthur J. Bilek and Alan S. Ganz, “The B-Girl Problem. A Proposed Ordinance,” Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science 56, no. 1 (March 1965): 39-44, https://doi.org/10.2307/1140594, 39.

35 Lighter; Amanda H. Littauer, “The B-girl Evil,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 12, no. 2 (April 1, 2003): 171 (text retrieved from Lexis-Nexis); “The Senate Did Not Know,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 24, 1906, 8.

36 The Vice Commission of Chicago, The Social Evil in Chicago: A Study of Existing Conditions (Chicago: Gunthrop-Warren Printing, 1911), 194, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b5188483?urlappend=%3Bseq=208%3Bownerid=102781651-226.

37 Bilek and Ganz, 39.

38 Henson v. City of Chicago, 114 N.E.2d 778 (1953), Illinois Supreme Court, https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/2045434/henson-v-city-of-chicago/.

39 Mark Jacob, “50 Years Ago, Female Bartenders Became Legal in Chicago,” Chicago magazine, February 3, 2020, https://www.chicagomag.com/city-life/february-2020/how-female-bartenders-became-legal-in-chicago-50-years-ago/.

40 “Mayor May Revoke Permits to Beaches,” Inter Ocean, June 21, 1911, 12.

41 “‘Protect Women From Thugs,’ Cry of Aroused Citizens, Who Will Hold ‘Safety Meeting,’” Chicago Examiner, June 11, 1911, 3.

42 “Mayor May Revoke Permits to Beaches,” Inter Ocean, June 21, 1911, 12.

43 Edgar Bronson Tolman, The Revised Municipal Code of Chicago of 1905 (Rochester, NY: Lawyers’ Co-operative Publishing, 1905), 441, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951002653828s?urlappend=%3Bseq=423%3Bownerid=13510798903152543-427.

44 “Woman Bathing in Bloomers Held,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 28, 1913, 1.

45 “Grizzly Bear (dance),” Wikipedia, accessed May 3, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grizzly_Bear_(dance).

46 Irving Berlin (words) and George Botsford (music), “The Grizzly Bear” (New York: Ted Snyder Co., 1910), Frances G. Spencer Collection of American Popular Sheet Music, Baylor University Arts and Special Collections Research Center, https://digitalcollections-baylor.quartexcollections.com/Documents/Detail/the-dance-of-the-grizzly-bear/1975735.

47 “In the Grizzly Bear’s Cave,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 26, 1911, metropolitan section, 1.

48 Gene Morgan, “Shall ‘Grizzly Bear’ Be Welcomed as Novelty or Barred as Disgrace? Society May Have to Decide Fate of Frisky ’Frisco’s Tough Dance,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 26, 1911, metropolitan section, 1, 4.

49 “‘Dago Frank’ Is Defying Police,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 29, 1911, 3.

50 “Pastors Assail Beach Rowdies,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 12, 1911, 3.

51 “Attack License of Wilson Beach,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 13, 1911, 3.

52 “Pastors Assail Beach Rowdies.”

53 “‘Protect Women From Thugs,’ Cry of Aroused Citizens, Who Will Hold ‘Safety Meeting,’” Chicago Examiner, June 11, 1911, 3.

54 “Pastors Assail Beach Rowdies.”

55 “City Brevities,” Chicago Daily News, June 10, 1911, 20.

56 “‘Protect Women From Thugs.”

57 “Pastors Assail Beach Rowdies.”

58 “Two Shot in Fight in North Side Cafe,” Chicago Examiner, June 11, 1911, p 1.

59 “North Shore Crime Blamed in Pulpits to Bathing Beaches,” Inter Ocean, June 12, 1911.

60 “Public Demands Revocation of Bathing Beach Licenses,” Chicago Examiner, June 13, 1911, 2.

61 “‘Protect Women From Thugs.”

62 “Pastors Assail Beach Rowdies.”

63 “North Shore Congregational Church, Wilson and Sheridan, Uptown Chicago,” Uptown Chicago History, Oct. 13, 2010.

64 Social Evil in Chicago, 89-91, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b5188483?urlappend=%3Bseq=103%3Bownerid=102781651-121.

65 “Public Demands Revocation…”; “Attack License of Wilson Beach,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 13, 1911, 3.

66 “Thugs Try to Burn Churches Fighting to Clean Up Beaches,” Inter Ocean, June 27, 1911, 1, 2.

67 “Fire at Church Crusade Result?” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 27, 1911, 4.

68 “North Shore Church Set Afire, Is Charge,” Chicago Examiner, June 27, 1911, 1.

69 “North Shore Forms an Anti-Vice Body,” Chicago Examiner, June 17, 1911, 4.

70 “Vigilantes to Guard Women,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 14, 1911, 4.

71 1911 Chicago city directory, at Fold3.com.

72 “North Shore Forms an Anti-Vice Body.”

73 “North Shore Church Set Afire, Is Charge.”

74 “Mayor May Revoke Permits to Beaches,” Inter Ocean, June 21, 1911, 12.

75 “M’Weeny to Aid in Bathing Beach War,” Inter Ocean, June 28, 1911, 5.

76 “Public Demands Revocation…”; “Attack License of Wilson Beach.”

77 “Pastors Assail Beach Rowdies.”

78 “Mayor Favors City Control of Beaches,” Inter Ocean, June 14, 1911, 3.

79 Daniel H. Burnham and Edward H. Bennett, Plan of Chicago (Chicago: Commercial Club, 1909), 50, https://archive.org/details/planofchicago00burnuoft/page/n89.

80 “One Fare for ‘L’s’ with Transfers; Council Demand,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 7, 1911, 1, 2.

81 “T. Chamales to Build Theater,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 4, 1909.

82 “Midway Theatre,” Cinema Treasures, accessed April 20, 2023, http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/5419.

83 1910 U.S. census, Illinois, Cook County, Chicago Ward 3, District 0225, Sheet 10B, at Ancestry.com.

84 “Jack Johnson Stops Moving Pictures of Wife’s Funeral,” Chicago Defender, September 21, 1912, 1.

85 Chicago city directories, 1911–1914, at Fold3.com.

86 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, December 31, 1911.

87 “Crooks Not Watched, Says South Sider,” Inter Ocean, February 24, 1912.

88 Chicago city directories, 1912–1914, at Fold3.com.

89 Abbott, Sin in the Second City, 278, 282-283, 287.

90 “Demand ‘Lid’ for North Shore Cafe,” Chicago Examiner, January 17, 1913, 4.

91 “Asks Dudley Back Charge,” Chicago Examiner, January 18, 1913.

92 “Sheridan Park Churches Lead Vice Crusade,” Inter Ocean, January 20, 1913.

93 “Vaudeville Gossip,” Inter Ocean, March 16, 1913, 28.

94 “Come On In: The Water’s Fine,” Inter Ocean, June 8, 1913, magazine, 1.

95 “Deeds Confirm Road’s Purchase,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 29, 1913, 16.

96 “News of the Day Concerning Chicago,” Day Book, February 12, 1915, 6; “News of the Day Concerning Chicago,” Day Book, June 29, 1916, 9; “Uptown Beaches,” Jazz Age Chicago, accessed April, 20, 2023, https://jazzagechicago.wordpress.com/uptown-beaches/; “Clarendon Community Center Park,” Chicago Park District, accessed April 20, 2023, https://www.chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks-facilities/clarendon-community-center-park; Charles H. Wacker, “Do the People Want Lake Michigan? Wacker Inspects and Finds They Do,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 18, 1916, 15.

97 “Plan a North Beach Body,” Chicago Daily News, August 4, 1917, 11.

98 Chicago Daily Tribune, December 27, 1931, picture section, 6.

99 “Montrose Beach,” Chicago Park District, accessed April 30, 2023, https://www.chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks-facilities/montrose-beach.

100 “$3,693,000 CWA Park Projects Nearly Finished,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 26, 1934, 12.

101 Arthur Evans, “Chicago’s Park Facilities Earn World Renown,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 4, 1935, 1.

102 “Clarendon Community Center Park.”