Chapter 5 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER—>

The man who created Green Mill Gardens—the forerunner of the Green Mill jazz club—was Greek immigrant Tom Chamales. More than anyone else, he was the guiding force of this place in its early heyday.

Even before Chamales took over Pop Morse’s roadhouse in 1910, he was already well known in Chicago, as the operator of a downtown bar called the Savoy. He’d made headlines as the saloonkeeper who fought in court against an effort to shut down liquor sales on Sundays.

“I have two birthdays,” Chamales told a reporter for Indiana’s Muncie Star newspaper reporter in 1962, when he was 83. “I was born April 3, 1878, under the former system used in Greece in reckoning years. When the calendar was changed, my birthday anniversary was advanced 13 days and now I celebrate on April 16.”1

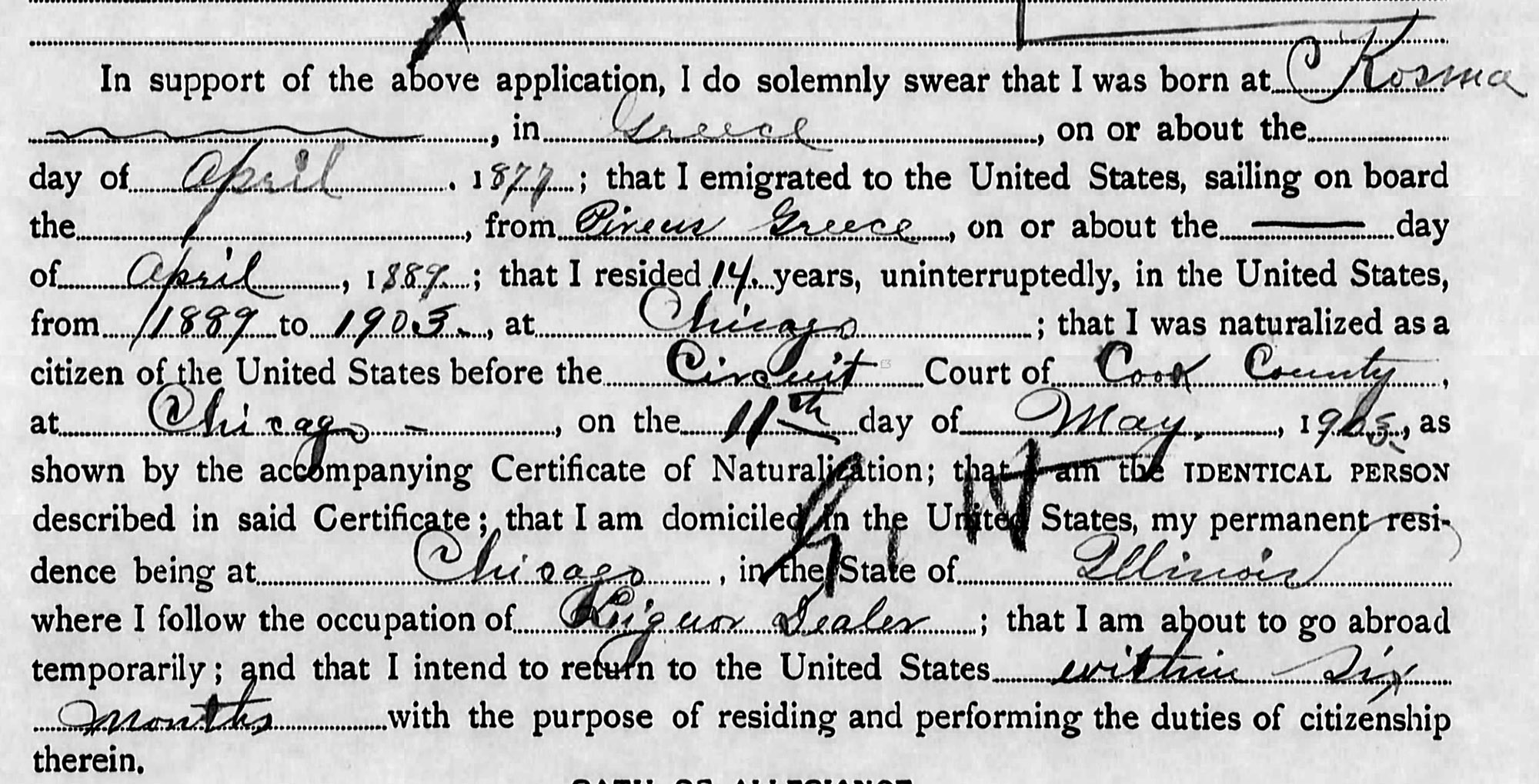

That may have been one year off, actually. According to his passport application, Chamales was born in April 1877 in Kosma, Greece. He’d sailed from Greece to America with his family in 1889, when he was 11 or 12 years old.2

That may have been one year off, actually. According to his passport application, Chamales was born in April 1877 in Kosma, Greece. He’d sailed from Greece to America with his family in 1889, when he was 11 or 12 years old.2

Soon after he arrived in Chicago, the young Chamales began working as a pushcart peddler selling bananas. He prospered in this line of work, according to the Muncie Star article. “He related that when his day’s work was done he added to his income by selling popcorn in Hyde Park at night,” the newspaper reported. “His trade was good.”3

Help from Eddie Foy?

According to legend, Chamales got some help from the actor Eddie Foy, who’s most famous in Chicago history as the star of Mr. Blue Beard at the Iroquois Theatre. When that theater caught fire during a performance on December 30, 1903, Foy stepped out onto the stage and urged audience members not to panic.

Foy survived, but 600 people died in the catastrophe. Foy later started a popular family vaudeville act featuring his children, Eddie Foy and the Seven Little Foys.

Claudia Cassidy, a longtime theater critic for the Chicago Daily Tribune, wrote in 1948 about the legend of how Foy helped Chamales.

Cassidy wasn’t clear about exactly when this happened, but she said it happened after Foy’s daughter Mary was born in 1901—perhaps when Foy was performing at the Iroquois Theatre in late 1903. Here’s how Cassidy told the story:

At that time there was in Chicago a Greek who sold flowers outside the theater where Foy was playing. He told the actor that when he was billed there business picked up. Naturally Foy was flattered, and when the Greek went on to say that with $200 he could open a store selling both flowers and fruit, he gave him $200. The Greek prospered. Eventually he became the owner of the Green Mill Gardens. His name was Tom Chamales. 4

Steve Brend, who started working at the Green Mill in the late 1930s and later owned the bar, also told the story to journalist Jacki Lyden, who published it in her 1980 book Landmarks and Legends of Uptown. As Brend told the story, it involved Tom as well as his brothers:

“And you know, they never would have got this place if it hadn’t been for Eddie Foy, the actor. … Yeah, he took a liking to them. It was when they had their flower stand in front of the old Iroquois Theater. Foy gave them $500 to open up a restaurant and they did, the Savoy, downtown, and when they had made enough money, they bought the Green Mill.”5

(Although Brend said Tom Chamales owned the Green Mill together with his brothers, none of the documents I’ve found show that his brothers had any ownership in the property or the business—at least until 1937, when William Chamales was listed in the telephone directory as the Green Mill Tavern’s proprietor.)

There may be some truth to this legend about Eddie Foy helping Tom Chamales, but it seems unlikely that it happened in 1903.

By that time, Chamales was already a saloon proprietor. He’d appeared in the Chicago city directory as a saloonkeeper in 1900, when he was in his early 20s. At that time, he was running a bar at 24 Clark Street with a partner named Samuel R. Donnellon. (The address changed to 203 North Clark Street in 1911; the location is near Clark and Lake Streets, at the north end of the Loop.)6

In a 1907 trial, Chamales testified about his early days working in the saloon business. “He started as a saloon porter, then became a bartender, then a saloon proprietor,” the Chicago Daily Tribune wrote, paraphrasing his testimony.7

In the first decade of the 20th century, Chamales lived at various places around the South Side and the Loop. Meanwhile, his brothers (and possibly some other relatives in the Chamales clan) were working in Chicago as confectioners, bartenders, saloonkeepers, fruit vendors, and clerks.8 By 1902, Chamales had a different saloon, at 356 State (now 602 South State Street).9

Chamales became naturalized as a U.S. citizen on May 11, 1903, the same day when he applied for a passport to travel abroad, declaring: “I follow the occupation of Liquor Dealer.”

The form noted that he was five-foot-seven, with black hair, dark brown eyes, and a fair complexion. His forehead and his mouth were both rated as “medium,” his chin and face were both described as “round,” and his nose was “straight.”10

The Savoy

For some reason, the city revoked his liquor license on July 8, 1903. Chamales filed a petition to get it back.

“Chamales declares that his license was revoked without any reasonable or sufficient cause and without any investigation,” the Inter Ocean reported.11

It’s unknown whether Chamales got his license restored. But by 1904, he was running another saloon, a block east of the previous one—at 363 Wabash (now 600 South Wabash Avenue). This was the place that became famous as the Savoy, although it’s listed in the city directory simply as the saloon of Thomas Chamales. (In that era, saloons were listed by the names of the proprietor.)

Chamales’s bar was apparently associated with or connected to the Savoy Hotel, at the southwest corner of Wabash and Harrison.12

A writer for the Chicagoan magazine later reminisced about New Year’s Eve in 1906, describing the scene at Tom Chamales’s saloon, when a police raid interrupted the festivities: “a mob of two thousand were pounding the tables with tin horns, demanding more wine, when the raiding squad herded them out to the sidewalk, singing, shouting and quarreling.”13

In late 1907, Chamales faced criminal charges for serving alcohol at his saloon on Sunday. That was legal under a Chicago ordinance in effect since 1874,14 but a state law made it a crime to keep a tippling house or any “place where liquor is sold or given away” open on Sundays.15

Chicago’s Republican mayor, Fred A. Busse, said saloons should be allowed to keep doing business on Sundays, but the Law and Order League persuaded the Cook County state’s attorney’s office to prosecute saloonkeepers violating the Illinois law.16

After midnight on the morning of Sunday, November 24, 1907, two detectives visited the Savoy and saw alcohol being served. One of the men tapped Chamales on the shoulder and asked, “Are you not afraid of being arrested for violation of the Sunday closing law?”

According to the detective’s later testimony, Chamales replied: “O, if they pinch me, it will be all right.”17

Tom Chamales on trial

Fifty-nine saloonkeepers were charged with violating the law. Chamales was the first to go on trial in the Chicago Municipal Court—a case that would serve as a sort of test, determining whether prosecutors could persuade a Chicago jury to convict someone for keeping a saloon open on Sunday.

Assistant state’s attorney James J. Barbour insisted on trying Chamales first,18 possibly because he believed the Savoy was “one of the worst of the disorderly saloons in Chicago.”19

Chamales was defended by Alfred Austrian, an attorney for the Retail Liquor Dealers’ Association. (Austrian was later legal counsel for the Chicago White Sox during the 1919 Black Sox scandal.20)

Chamales was defended by Alfred Austrian, an attorney for the Retail Liquor Dealers’ Association. (Austrian was later legal counsel for the Chicago White Sox during the 1919 Black Sox scandal.20)

Austrian introduced some photos of the Savoy as evidence for the jurors to examine.

“This is one of the largest restaurants in the city,” he said, “and knowing the wild manner in which these detectives will testify, we have taken the precaution to have photographs taken of the interior, and we will show them to you, so that you can see for yourselves whether or not this is a low, bawdy house or respectable place.”21

The Law and Order League’s counsel was worried during jury selection. As the Inter Ocean noted, “There was not a juror who did not plead guilty to liking an occasional glass of beer—sometimes on a Sunday.”

The newspaper described a “motley assemblage of people” crowded in Judge Frederick L. Fake’s courtroom. “The members of temperance societies jostled with saloon-keepers.”22

In his opening argument, the prosecutor told the jurors: “If Tom Chamales, who came to this fruitful country from Greece some years ago, does not like the laws of this country he can go back to the country he came from. There is no doubt about the law in this case.”23

Barbour continued: “I shall prove that Thomas Chamales, commonly known as Tom Chamales, kept his saloon open on the Sunday in question, November 24, from midnight to midnight. We start with midnight, when we find the place filled with men and women and with boys and girls—the boys and girls from 18 to 21 years old—and they were drinking beer and whisky, Champagne, and other wines, and were carousing and drunk. … I will show that in different parts of the room girls were singing in maudlin tones—”

Austrian jumped up from his chair. “I object to this language,

he said. “Nothing is charged in the information but the sale of liquors in an illegal manner.”

“Mr. Barbour may tell what he expects to prove,” the judge said.

“Just as our witnesses left the place on that Sabbath morning,” Barbour continued, “a chorus of voices began to sing, ‘What the hell do we care!’ and then an 18-year-old girl, who had been drinking, started for the door, but turned around, and, putting her hand to her mouth, gave a yell like an Indian.”

For his part, Austrian argued that Chicago’s city charter gave it the power to regulate saloons, overriding the state law. He described the investigators who’d visited the Savoy as “the hirelings of a ‘goody goody’ organization.”

Austrian said, “It is not the character of Mr. Chamales or his place of business that makes the issue here, but the one question whether he violated the law by selling liquor in Chicago on Sunday.”

Austrian stipulated that, yes, the Savoy had indeed served beer on that Sunday. But as far as Austrian was concerned, the facts of the case weren’t in dispute. The question was whether someone like Chamales should be punished under that state law for doing something allowed under a city ordinance.

When Chamales took the witness stand, “He testified that he is the owner of the Savoy, which, he insisted, was more of a restaurant than a saloon,” the Tribune reported.24

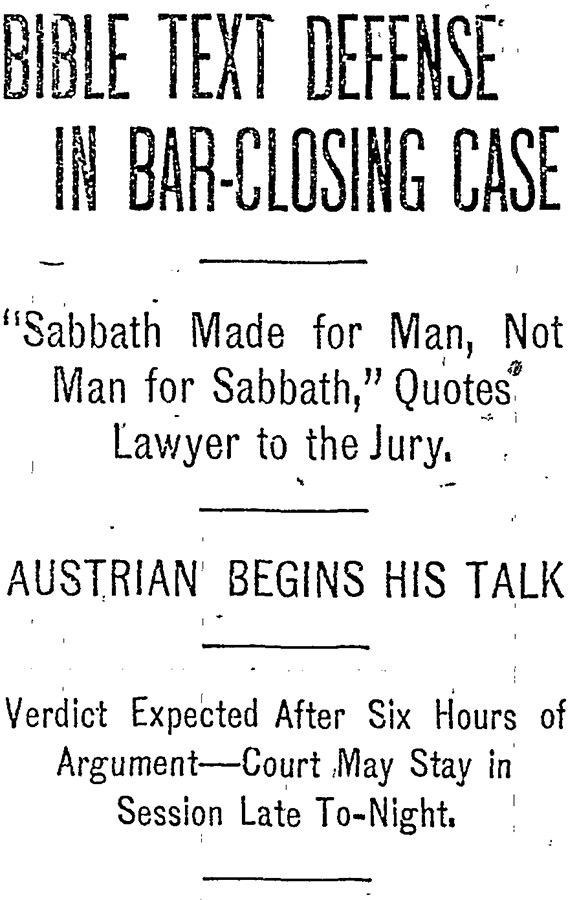

During his closing argument, Austrian said he saw no reason why selling alcohol should be a criminal act on Sundays.

“The sabbath is made for man, not man for the sabbath,” he said. And then he praised immigrants like Chamales, who’d come from other parts of the world to form a new community in Chicago. “This mixture is the backbone and sinew of American citizenship,” Austrian said.25

As the lawyers argued about the instructions Judge Fake would give the jury, Austrian made a bold assertion. “The jurors are judges of the law as well as the facts,” he said. “They may swear that they know the law better than the court, and I am willing to take my chances that this jury may know the law better than this court.”26

He was making the case for jury nullification—when jurors, based on their own sense of justice, refuse to follow the law, acquitting a defendant even if the evidence points to an incontrovertible verdict of guilty.27

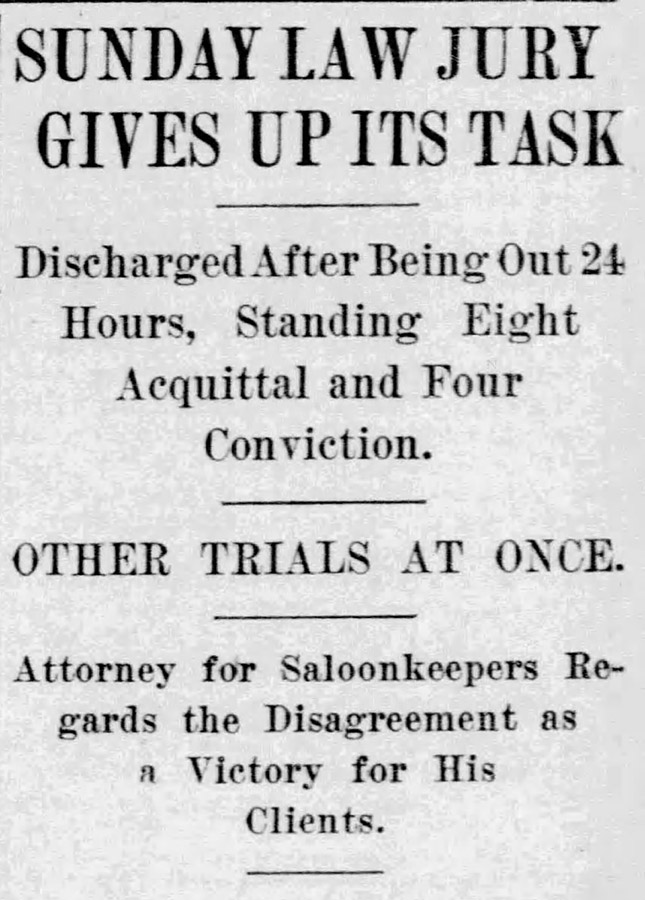

After 24 hours of deliberation, the jurors could not agree, with eight voting for acquittal and four for conviction. “We’ve agreed to disagree,” a juror remarked, as the case ended with a mistrial.28

But the prosecutors quickly brought the charges back for another trial.

“Bigotry is the motive impelling this prosecution, and bigotry is a passion that fattens with what it feeds on, and its appetite increases with each new enjoyment,” Austrian told the new set of jurors. “Isn’t it strange that it should remain for the bigots of the so-called Law and Order League to be the first to tell state’s attorney [John J.] Healy that fossil legislation, exhumed from a forgotten and neglected grave, was applicable to Chicago?”

Judge Arnold Heap read the state statute to the jurors, explaining that it was a crime to serve alcohol at a saloon on Sundays anywhere in Illinois.

“It is constitutional and valid and applies to Chicago as well as to all other parts of the state, and is in full force and effect in this city at the present time,” Heap said. He warned the jurors not to override the court’s opinion “unless they felt on their oaths as jurors that they knew the law better than the court.”29

The jurors began deliberating at 4 p.m. on a Thursday.30 They were still talking around midnight, when a juror made a telephone call, ordering some beer (either four quarts or a dozen bottles, according to different reports). A clerk sent the beers to the jurors’ room, but the bailiffs stopped the delivery.31

The jurors reached a verdict by 8 a.m.,32 and a clerk read it aloud: “We the jury find the defendant not guilty.”

According to the Daily News: “Chamales was at once surrounded by a throng of friends, who congratulated him and some of the spectators began to clap their hands.”33

Judge Heap did not thank the jurors for their service.34 The jurors had done exactly what he’d warned them not to do. Some people speculated that they’d been angered by the bailiffs’ refusal to drink beer.35

“This demonstrates that this dead law can’t be enforced,” Austrian remarked.36

“I can’t understand the verdict,” assistant state’s attorney John E. Northup said, insisting that his office would continue prosecuting other saloonkeepers for the same violation of state law. “It looks hopeless, but we will take up another case at once and will not despair.”37

State’s attorney Healy remarked, “I expected the Chamales jury to convict. I didn’t see how it could do otherwise. If it touches on anarchy for a jury to disregard plain law, we must make the most of it.”

“The verdict in the Chamales case does not determine the merits of the points at issue,” said Adolph Raphael, an attorney for the Law and Order League. “It proves simply that Alfred Austrian made monkeys out of 12 men and blinded them to the law and their duty.”

Law and Order League leader Arthur Burrage Farwell said: “I never believed it would be an easy matter to close Sunday saloons in Chicago. But I believe the law-abiding people of this city will prevail in the end, and the Sunday saloon will yet be a thing of the past.”

But Austrian told the Inter Ocean: “No jury can be found in Chicago that will convict a saloonkeeper for keeping open on Sunday. The Chamales juries were fine, intelligent bodies. They were composed of men from all districts of the city and all walks of life. Out of the 24 men on the juries in the two trials, 20 voted for acquittal and only four for conviction.”38

Headlines across the country

The trial was covered by the Associated Press and the United Press, and stories about it appeared in newspapers across the country, often on the front page. The national press coverage may have reinforced widespread perceptions of Chicago as a lawless city.

“Chicago Jury Refuses to Convict Saloon Keeper of Violating the Law,” said a headline in the Los Angeles Times,39 while the Des Moines Register noted: “JUDGE’S INSTRUCTIONS IGNORED.” 40

The Kansas City Star called it “A Verdict Against the Lid.”41

The Topeka Daily Capital predicted that it “may prove to be the decisive battle between the saloon men of Chicago and the Law and Order league.”42

The Arkansas Democrat said it was “a signal defeat” for the Sunday closing crusaders.43

In Munster, Indiana, the Lake County Times urged prosecutors to continue the trials against Sunday saloons, in spite of this “astonishing verdict.” But if juries continued voting not guilty, the newspaper acknowledged it might be necessary to repeal the state law.

“Laws which are not enforced are only calculated to lessen the respect of the public for laws in general,” the editorial said.44

The Voter, a monthly publication pushing for reform in Chicago politics, also commented on the Chamales trials, connecting them with a history stretching back to the 1870s:

When the late Joseph Medill was elected mayor of Chicago on the Citizens’ Fireproof ticket in 1871, he said that he would close the saloons on Sunday. He did and he kept them closed on Sunday during his entire term. At the next election the Sunday saloon element swept the man they supported into office by a big majority. Since then the saloons of Chicago have been open on Sunday in direct defiance of the state law which prohibits them from doing business on the first day of the week. No mayor since Joseph Medill has attempted to enforce the law and no state’s attorney has dared to make a fight on his own initiative. None will. It would spell political destruction.

Arthur Burrage Farwell and his Law and Order League are now crusading against the Sunday saloon in Chicago. They have caused the arrest of a number of saloon keepers and one of them, Tom Chamales, has been tried. The first time a jury disagreed. The second time the jury found him “not guilty,” although he admitted that his saloon was open in defiance of the state law.

Of course, the saloons in Chicago are illegally open on Sunday and under the law they should be closed. But they will not be closed because the people of Chicago do not obey laws that do not suit them. When a law fails to meet the approval of any considerable number of Chicagoans they resolve that it is a “dead letter” and that is the end of the matter.45

Although it seemed like a losing battle, the Law and Order League continued its campaign against saloons in 1908.46

This was all part of the national temperance movement, which would lead to ratification of the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1919, prohibiting the making, transportation, and sale of alcohol.

Chamales heads north

But in the meantime, Tom Chamales continued his career as a saloonkeeper and restaurateur.

In 1910, he struck a deal to take over Pop Morse’s roadhouse. This would be a big change for Chamales, taking him seven miles north from the Savoy. As he headed north, he followed in the footsteps of his brothers James and George, who’d opened the Chamales Bros. saloon at Clark Street and Devon Avenue a couple of years earlier.47

Tom Chamales did not buy the Morse roadhouse property at the northwest corner of Evanston Avenue (now called Broadway) and Lawrence Avenue. The land was still owned by Catherine Hoffman (Pop Morse’s daughter and heir) and her husband, Charles Hoffman. But they began leasing it to Chamales, while selling the saloon’s stock and fixtures to him. A Tribune article explained the lease:

… Thomas Chamales leased from Charles Hoffman the property on the northwest corner of Lawrence and Evanston avenues, generally known as the “Pop” Morse roadhouse. The lease covers a period of fifteen years, the rent for the last five years being $11,000 per year, and the whole aggregating $158,000. The lessor has also purchased outright the stock and fixtures of the old establishment at a price to be about $20,000.

By the terms of the lease Mr. Chamales must improve the property at least $30,000 within six months. At present it is improved with a frame building, the remainder of the lot being given over to a garden with orchestra arrangements. The lot extends 138 feet on Evanston avenue and 150 feet on Lawrence avenue.

It is understood that Mr. Chamales will add to the present building, and will also inclose the entire garden, so arranging it that the whole can be thrown open in warm weather. It will be run as a music hall, restaurant, and garden. The lease was negotiated by Young & Johnson, brokers.48

Thus began the Tom Chamales era at this spot, which would soon become Green Mill Gardens. This also marked the beginning of the relationship between Chamales and the Hoffmans, which would eventually end up in a bitter legal battle.

Continue reading with the next chapter: The Battle Over Beach Rowdies, B-Girls, and Disorderly Women

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER—>

Footnotes

1 Dick Greene, “Seen and Heard in Our Neighborhood,” Muncie (IN) Star, March 6, 1962, 4.

2 U.S. Passport Applications, No. 71150, at Fold3.com.

3 Muncie Star.

4 Claudia Cassidy, “Foys Will Be Foys,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Aug. 15, 1948, magazine, 7, 10.

5 Jacki Lyden, Landmarks and Legends of Uptown (Chicago: Jacki Lyden, 1980), 29.

6 1900 Chicago city directory.

7 “Sunday Law Case to Jurors Today,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 12, 1907.

8 Chicago city directories, 1900–1909, at Fold3.com.

9 1902 Chicago city directory

10 Passport applications.

11 “Wants License Restored,” Inter Ocean, July 19, 1903.

12 1904 Chicago city directory

13 Paul T. Gilbert, “That Was New Year’s,” Chicagoan, December 1931, 29-30. http://chicagoan.lib.uchicago.edu/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/mvol-0010-v012-i05/mvol-0010-v012-i05.xml#page/30/mode/1up.

14 City advertisement, Inter Ocean, March 21, 1874, 7.

15 Harvey B. Hurd, ed. and comp., The Revised Statutes of the State of Illinois, 1901 (Chicago: Chicago Legal News Company, 1901), chapter 38 § 259, 638, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.35112105473971?urlappend=%3Bseq=670%3Bownerid=13510798902240829-694.

16 “Dispute Now Rends Anti-Saloon Ranks,” Inter Ocean, December 11, 1907.

17 “Saloon Defense to Be Argument,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 25, 1907.

18 “Dispute Now Rends Anti-Saloon Ranks,” Inter Ocean, December 11, 1907.

19 “Sunday Law Case to Jurors Today,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 12, 1907.

20 Bill Lamb, “Alfred Austrian,” Society for American Baseball Research, accessed March 25, 2023, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/alfred-austrian/.

21 “Plan War as Saloon Case Goes to Trial,” Inter Ocean, December 12, 1907, 7.

22 “Dispute Now Rends Anti-Saloon Ranks,” Inter Ocean, December 11, 1907

23 “Asks Verdict of Guilty,” Chicago Daily News, December 12, 1907, 2.

24 “Sunday Law Case to Jurors Today,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 12, 1907.

25 “Bible Text Defense in Bar-Closing Case,” Chicago Daily News, December 13, 1907, 1.

26 “Asks Verdict of Guilty,” Chicago Daily News, December 12, 1907, 2.

27 J.B. Weinstein, “Considering Jury Nullification: When May and Should a Jury Reject the Law to Do Justice,” American Criminal Law Review 30, no. 2 (Winter 1993): 239-254, https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/considering-jury-nullification-when-may-and-should-jury-reject-law.

28 “Sunday Law Jury Gives Up Its Task,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 15, 1907.

29 “Second Deadlock on Sunday Drams,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 27, 1907.

30 “Next Case May End Night for ‘Dry’ Sabbath,” Inter Ocean, December 28, 1907.

31 Associated Press, “Chicago Jury Is for Sunday Saloon,” Joliet Evening Herald News, December 27, 1907; United Press, “Sunday Saloon Wins in Chicago,” Des Moines (IA) Register, December 28, 1907, 1.

32 Inter Ocean, December 28, 1907.

33 “Closing Case Lost; Crusade Is Still On,” Chicago Daily News, December 27, 1907, 1.

34 “Next Case May End Night for ‘Dry’ Sabbath,” Inter Ocean, December 28, 1907.

35 Des Moines Register, December 28, 1907.

36 Chicago Daily News, December 27, 1907.

37 Joliet Evening Herald News, December 27, 1907.

38 Inter Ocean, December 28, 1907.

39 “Sunday Closing Loses,” Los Angeles Times, December 28, 1907, 2.

40 Des Moines Register, December 28, 1907.

41 “A Verdict Against the Lid,” Kansas City (MO) Star, December 27, 1907, 1.

42 “Chicago’s Sunday Closing Fight May Come to End Soon,” Topeka (KS) Daily Capital, December 29, 1907, 1.

43 “Sunday Crusaders Active in Chicago,” (Little Rock) Arkansas Democrat, December 29, 1907, 3.

44 “Let the Good Work Go On,” Lake County (Munster, IN) Times, December 28, 1907, 4.

45 The Voter, January 1908, 27. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112110170609?urlappend=%3Bseq=505%3Bownerid=13510798903703063-523.

46 One example: “Battle on Healy Becomes a Test,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Aug. 6, 1908, 1.

47 1908 Chicago city directory.

48 “‘Pop’ Morse Roadhouse Leased,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 22, 1910, p 13.