Chapter 4 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

When I moved to Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood, one of the local legends I heard involved Abraham Lincoln. Supposedly, he’d stopped at a local saloon called the Sunnyside Inn, which was somewhere near the street called Sunnyside Avenue.

When journalist Jacki Lyden was in Uptown more than four decades ago, she heard the same thing. She wrote about the Sunnyside Inn in her 1980 book, Landmarks and Legends of Uptown, noting: “Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln were reported to eat there occasionally.”1

Sadly, this is one legend I have not been able to confirm. It could be true, but I haven’t found evidence for it.

The Sunnyside Inn was a real place, though—one of the area’s most famous roadhouses and “cemetery saloons” in the 19th century. In many ways, it set an example for other local roadhouses, including two that evolved into noteworthy entertainment venues, Green Mill Gardens and Rainbo Gardens.

“Along the old Green Bay road years ago were many roadhouses or taverns,” Chicago’s Inter Ocean newspaper wrote in 1903. “The one which stood at what is now Sunnyside park was the best known of them all.”2

When exactly did the Sunnyside saloon and hotel begin serving travelers on Green Bay Road, the highway that we now call Clark Street? That’s something of a mystery. I emailed Martin Tangora, who’s done a lot of research on the neighborhood’s history, to ask him if he knew when the Sunnyside began. “It’s difficult to get a good, reliable, grip on the history of that old inn,” he replied. “I have worked on it without getting much satisfaction.”3

In 1903, the Inter Ocean reported that the inn had been in business since “the days when Chicago was little more than a village on the swampy shores of Lake Michigan.” It was a time when “one did not need to go many miles to find Indians.” That’s vague, but it seems to be describing the 1830s or 1840s. In that early era, the inn didn’t have any name, according to the Inter Ocean.

But the newspaper also reported, “The old roadhouse was at first owned by a toll-road company.” The Rosehill and Evanston Road Company began running the toll road in 1860, which suggests the inn opened around that time. (If so, that sounds late for visits by Lincoln or Douglas. Both were running for president in 1860, and Lincoln was headed soon for the White House.)4

The 1860 U.S. census lists four German immigrants in Lake View Township who were saloonkeepers: Francis Barr, Leonard Mayer, Edward Zentschel, and George Oertel, who ran the Pleasant Garden & Lager Beer Saloon. In addition, Massachusetts native Henry W. Chester was running a local hotel.5 It’s unknown exactly where these establishments were located.

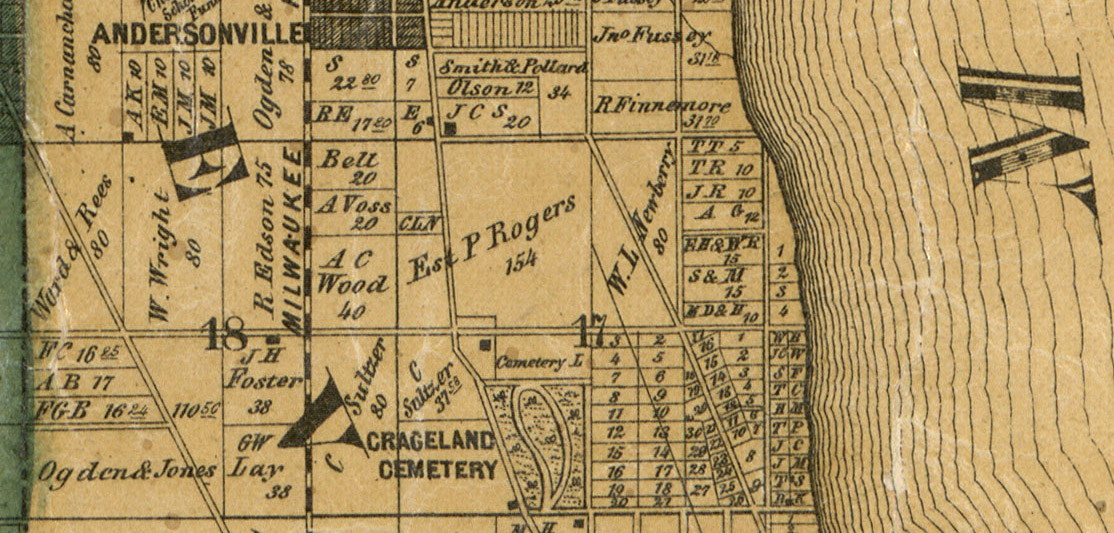

The Sunnyside stood on that sandy rise in Chicago’s topography, the Graceland Spit. “To the east of the roadhouse was sandy waste,” the Inter Ocean wrote. “To the west were the undulating ridges piled up ages ago by the winds and waters of the lake.” 6

A survey of Green Bay Road from October 1857 does not the Sunnyside. The map didn’t necessarily include every building along the road, but it does show some other buildings. This suggests that the Sunnyside didn’t yet exist.7

The Sunnyside is also absent from a fairly detailed 1861 map, which shows some major buildings. That map shows the estate of Phillip Rogers as the owner of a large swath of land north of Graceland Cemetery—including the Sunnyside’s later location.8 Rogers, an early Irish settler who’d died in 1856, owned some 1,600 acres of government land, including the future neighborhood named after him, Rogers Park.9

“Cap” Hyman’s resort

The notorious and wealthy Chicago gambler Samuel “Cap” Hyman purchased the Sunnyside in 1866. Author John J. Flinn described Hyman “a professional blackleg and gambler, who was wont while in liquor to go about town intimidating people by whipping out a revolver and threatening death to anybody who crossed him in any way.” 10

Just a few months before Hyman bought the Sunnyside, he’d made news when he was hurled down a flight of stairs by his wife, brothel owner Annie Stafford.11

In December 1866, an advertisement in the Chicago Times mysteriously teased the inn’s opening with this terse announcement12:

Hyman held a dedication party for Chicago’s “demi-monde” at the Sunnyside on December 19, 1866. “The list was select, embracing chiefly the women keepers of some of the more fashionable brothels, and those who contribute most liberally to their support,” the Tribune reported.

The newspaper described a quarrel that broke out among some of these women during the party, concluding: “How much hair bestrewed the floor, what became of the waterfalls and the hoop skirts in the conflict, will never be known.”13

When these quarrelers testified later in a police court, “There was some very strong swearing upon both sides, but not of the character reported to have occurred at the party,” the Tribune reported. According to the testimony, Sunnyside guests exchanged insults and blows. Hair and noses were grabbed.

And the most insulting testimony was about Hyman’s wife. “Witnesses … spoke in most vile disparagement of the character of Annie Stafford Hyman,” the Tribune observed.

But in the end, the episode did not amount to much, as least as far as legal consequences. “It was fun for the boys to see ’em fight for a while, but for the credit of the house it was soon stopped. There did not seem to be sufficient evidence in the case to warrant the holding of the parties for trial upon the charge of riot, and they were discharged.”14

The Sunnyside was “a rendezvous for the gay set of the town,” the Inter Ocean recalled decades later. “Its prize fights, its sensational poker games, its horse races, and the convivial company at the old roadhouse made it famous as the abiding place of a wanton company.” The patrons “did not stand upon conventionalities. There were hot words and hard fights. Rumors of encounters at the resort almost daily drifted down into Chicago.” 15

In 1867, newspapers mentioned the Sunnyside when they reported on crimes in the roadhouse’s vicinity. In one incident, three “pugilists” were “charged with riot, having participated in the rough-and-tumble that occurred … near Sunnyside.”16

And the Tribune reported about a “Brutal Outrage Upon a Woman,” clearly describing a rape without ever using that word. The young woman was attacked by two men who were taking her on a hack ride. They’d told her they were going to Sunnyside, but then they took her to “an unfrequented locality” where they viciously assaulted her.17

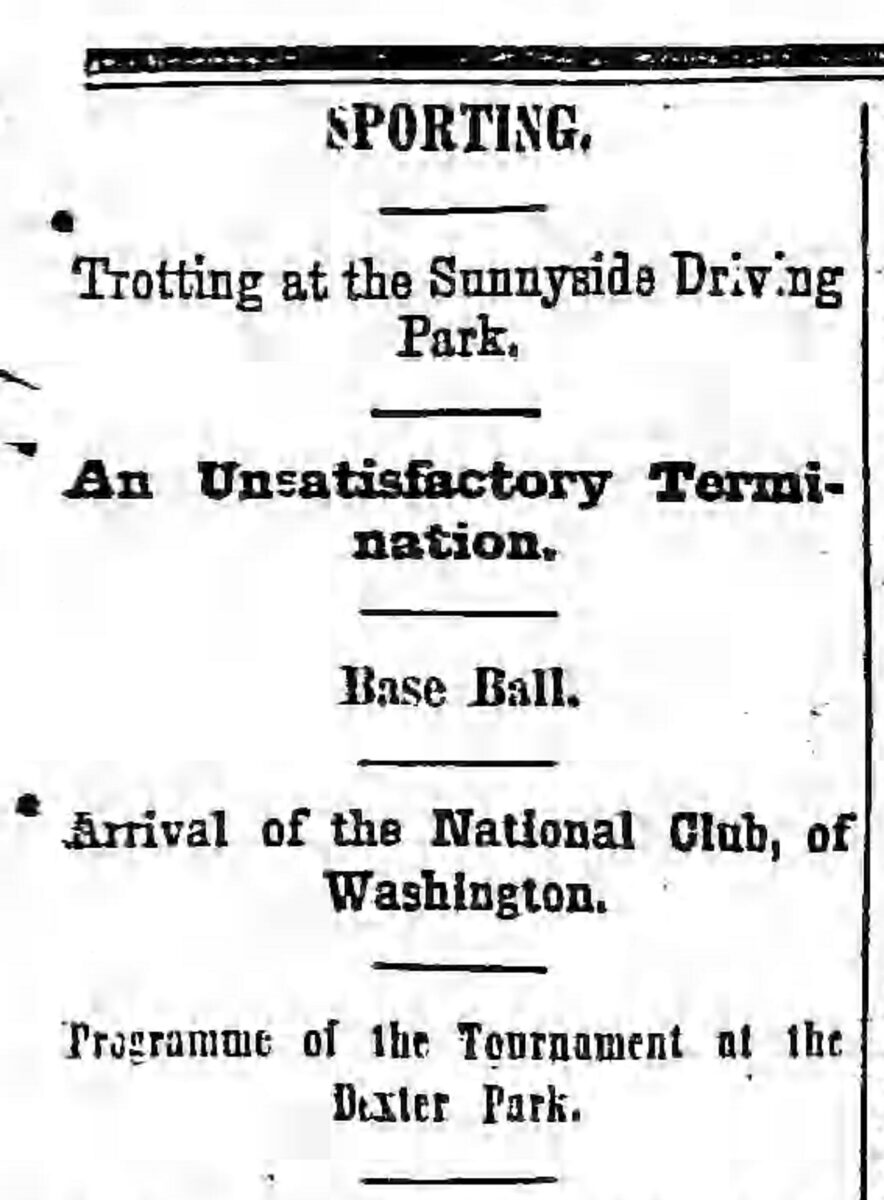

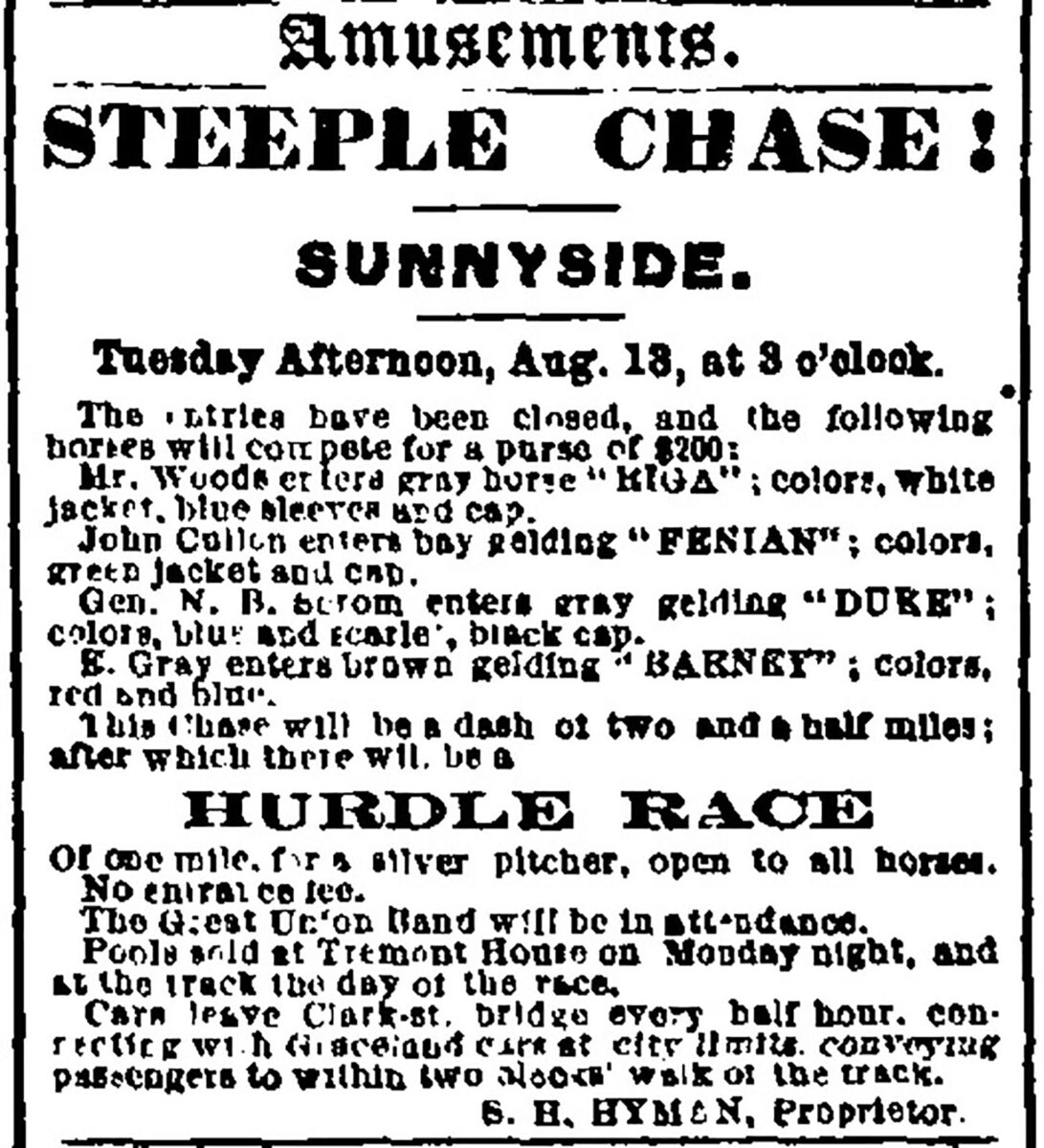

In 1867 and 1868, Hyman operated a track for horse racing across the street from his inn, apparently on the west side of Green Bay Road (Clark Street). Usually referred to as Sunnyside Driving Park, it hosted harness racing as well as an occasional “running race.”18

On August 13, 1867, Sunnyside held a steeple chase—a novel event at that time. Described by the Chicago Republican as the “Introduction into Chicago of an Old English Diversion,” the equestrian competition attracted a crowd of three thousand spectators.19

The racetrack suggested that Chicagoans could reach Sunnyside by taking a Clark Street streetcar in the city, then transferring to a Graceland Cemetery omnibus, and finally walking two blocks north from the cemetery entrance.20 But horse-drawn vehicles were the preferred mode of transportation for many folks. The Republican described people rushing north up Green Bay Road to attend the steeple chase:

… the road presented a very gay and pleasant appearance. About every vehicle known to man, besides several others whose actual genus is not known, was represented. … all restraints were thrown to the dogs, and everybody did his utmost to get to the scene of the contest first. Fat old gentlemen on horseback; thin ones in buggies; three in a buggy, six in a hack; fifteen on a dray, and a hundred and fifty on a horse-car—all hurried along in the most energetic manner …

The Republican’s reporter also went up to the Sunnyside’s cupola and looked around:

To the south, enshrouded in a cloud of its own making, lay the great city, quiet and still like a giant asleep. To the north lay the woods, bounded in the distance by the beautiful prairie. To the east rested the peaceful lake, dotted here and there by the fleecy sails of outgoing or incoming vessels. … To the west stretched prairie and woodland, happily relieved by farm-house and suburban residence. …

At our feet lay the stables and stable yards, filled in every corner with vehicles and the horses thereof. Across the road was the pleasant little track, dotted all over with interested active specimens of humanity, running about to see the various points of the course, or else resting upon the sward in sheltered spots, and listening to the strains of an excellent band of music.

During the two-and-a-half-mile steeple chase, the horses went around the track on the west side of Green Bay Road. Then they followed a route that looped around to the east of the hotel, jumping over hurdles, ditches, and fences along the way. When they reach a wooded area east of the Sunnyside—perhaps around where Dover Street is today—the riders turned their horses north and then back west, returning to the track.21

The genesis of Ravenswood

Cap Hyman’s reign at the Sunnyside did not last long. In March 1869, an advertisement in the Chicago Republican said that the hotel was for sale or rent, along with its eight-acre property. “This property will be sold at a bargain, if applied for soon, or will be leased at a low rate for a term of five years. This is a rare chance for a person desirous of engaging in the hotel business.”22

This announcement appeared as the land across the street from the Sunnyside was being subdivided and sold as residential lots. According to the Chicago Evening Post, the developers had met in 1868 during “a conference of several days with closed doors,” where they came up with a name for the suburban village they were creating. They called it Ravenswood.23

Historian Caroline M. McIlvaine, a librarian at the Chicago Historical Society, told a more colorful version of the name’s origin in a 1927 Chicago Daily News column: A group of Chicagoans went looking for a good place to build a suburb in September 1868, ending up at a grove of giant oaks around the present-day intersection of Clark Street and Leland Avenue. According to McIlvaine:

… they spent so much time examining the property that the sun sank low in the west, and with the lengthening shadows the ravens began their evening flights, their cries coming across the prairie from the woods on the north branch. Some one, no doubt a Scotchman, suggested the romantic name of Ravenswood for the new suburb, and it was adopted then and there. 24

She seemed to be suggesting that “Ravenswood” was a reference to the fictional Scottish castle in Sir Walter Scott’s novel The Bride of Lammermoor. (This was also nineteen years after Edgar Allan Poe’s poem “The Raven” was published, but that would be an unlikely inspiration for the name of a residential development.)

Did those developers actually see ravens in Ravenswood in 1868? At one time, ravens “not uncommon” in northeast Illinois, but by 1876, they were rare in the state, according to ornithologists.25 Today, the common raven (Corvus corax) is rarely if ever seen in Chicago, but the city has plenty of American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos), a similar-looking but smaller species.

As the Forest Preserve of Will County noted: “While crows are common across the state, ravens are only very rarely recorded here, according to the Illinois Natural History Survey. In fact, bird observations reported via eBird show only one raven sighting in the state, in Lake County.”26 It’s possible that Ravenswood’s developers actually saw some crows and mistook them for ravens. (“Crow Wood” may not have been such an attraction name.)

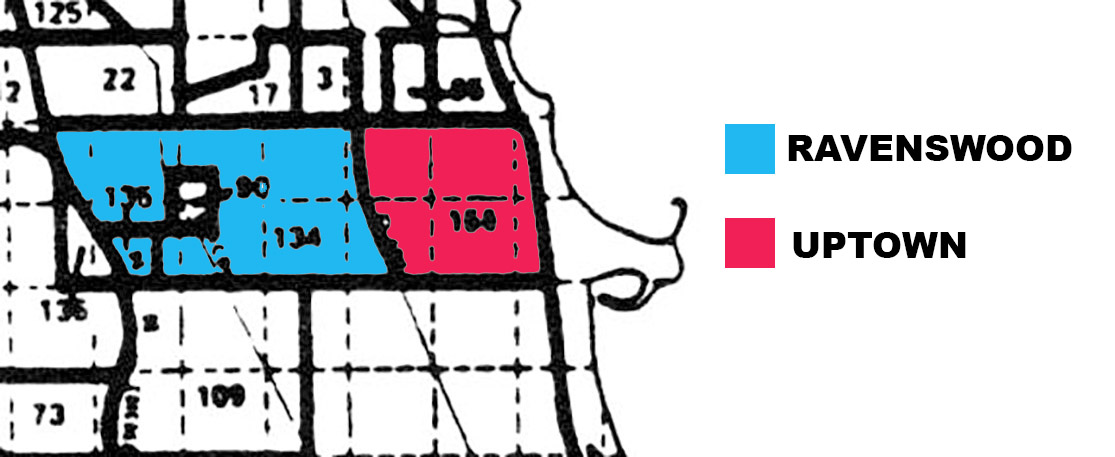

The original Ravenswood subdivision had boundaries zigzagging within an area encompassed by Robey (now Damen) on the west, Lawrence on the north, Berteau on the south, and Green Bay Road (now Clark Street) on the east. In the coming years, nearby land was subdivided, entering Cook County’s property records as “additions” to Ravenswood.27

Ravenswood’s present-day boundaries, like those of many Chicago neighborhood boundaries, are debatable. “It’s the ghost neighborhood of Chicago, whose presence isn’t acknowledged in any substantial way, only felt,” Ed Zotti wrote in a 2009 Chicago Reader article.

According to the map of Chicago’s 77 community areas, the land between Ashland Avenue and Clark Street, from Montrose north to Foster, is all part of Uptown:

But on other maps (including a map of 178 neighborhoods approved by the City Council in 1993), this trapezoid is part of Ravenswood—with Clark Street serving as a dividing line between Ravenswood and Uptown.

The Sunnyside Inn was sometimes referred to as a Ravenswood establishment28—even though it was actually across the street from the Ravenwood subdivision, which included the land where the Sunnyside Driving Park had been. The new houses were replacing Wood’s Nursery, which grew a variety of trees.

In April 1869, an advertisement announced that the Ravenswood Land Company was selling the nursery’s 30,000 evergreen trees. “This will be the last chance to procure trees from this celebrated Nursery, as it is the intention of the proprietors to divide the property into lots and blocks, and sell for building purposes.”29 As the Ravenswood Land Company laid out the neighborhood, it named a new street after the hotel, calling it Sunnyside Avenue.30

The Evening Post rhapsodized about “the beautiful suburban village of Ravenswood,” describing it as “luxuriating in boundless shade afforded by native oak and larch, reinforced by a lavish cultivation of Austrian pine, spruce and white birch, and breathing a fragrance that might be supposed to have existed in the Elysian fields.” The article concluded:

In the writer’s opinion, no more beautiful country seat exists than Ravenswood. Nestled in foliage, eighteen feet above the North Branch, and capable of complete drainage, possessing a fertile soil adapted to the growth of any plan capable of propagation in this latitude, nourishing evergreens that rear their drooping forms ten feet above their mother earth, and diversified with charming meadows, Ravenswood challenges suburban competition.31

The emergence of Ravenswood also meant that the Sunnyside and other saloons along Green Bay Road now had more neighbors—including people who would complain about those saloons.

Daniel Downing’s Sunnyside

Daniel Downing and his wife, Sophronia Hines, soon took over the Sunnyside.32 Both born in Massachusetts, they’d gotten married in Brattleboro, Vermont, in 1840.33 By 1860, they were running a hotel in unincorporated Cook County west of Chicago.34

In 1870—around the time when they bought Sunnyside—the U.S. census showed them running a hotel in Jefferson Township, with Rose Hill listed as their post office. That indicates it was near Rosehill Cemetery’s west side. By this time, Daniel was 55 and Sophronia was 51.35

Some sources say Daniel Downing constructed the Sunnyside Inn in 1870. If so, did it replace the previous building at the site? According to a Chicago Daily News story published in 1940—seventy years after the fact—Downing celebrated the inn’s opening on a winter evening, when “the woods lining the road to Ravenswood rang with the sound of sleighbells and merry laughter as dozens of Chicago’s gayest blades made their way to the gala opening night at Sunnyside Inn.”

The story continued: “The spacious inn with its broad white verandas had just been completed and Daniel Downing, whose faith in the future of Ravenswood had led him to finance the building, was sparing no expense to see that this first night would be something to remember.”36

Under Downing’s ownership, “fights and poker games became a thing of the past” at Sunnyside, the Inter Ocean recalled. Instead, the place gained renown for Sophronia’s cooking.37

A failed crackdown on Sunday drinking

One day in October 1872, when the city was enforcing the usually unenforced law against serving alcohol on Sundays, the Tribune reported that “many young bloods … found their way to the drinking-places beyond the North Side city limits”—including Sunnyside. “The dusty road and warm sunshine produced thirst, which was probably increased by the consciousness that no liquor was to be obtained near home,” the Tribune wrote. “ … as long as Sunnyside and Downing’s are within reach, this appears to be inevitable.”38

This wasn’t the first time that conservative politicians had tried to stop Chicagoans—especially immigrants—from drinking on Sundays. The Lager Beer Riot of 1855 was a reaction against a similar move by a “Know-Nothing” nativist mayor, Levi Boone.

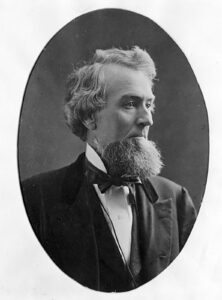

The 1872 crackdown was ordered by Chicago’s mayor, Joseph Medill (who’s famous for his role leading the Chicago Tribune). Medill took on this battle reluctantly, after being hounded by reformers who insisted that Chicago should enforce its law against saloons serving liquor on Sundays.39

When temperance advocates visited Medill at City Hall, he told them that saloons “have never ceased to furnish liquor to their customers on any Sunday since the city was incorporated, more than thirty years ago.” He added: “Two-thirds of the men of Chicago are of European birth, and nearly all of them were accustomed to drinking liquor on all days of the week, and to regard it no more immoral to drink on Sundays than on week days.”40

Nevertheless, Medill ordered the police to close saloons on Sunday, outraging the city’s German immigrants. “But such efforts largely proved to be futile,” historian Karen Sawislak wrote in Smoldering City. Medill stepped down from the mayor’s office before his term was up. In the next election, a calling itself the People’s Party defeated the Law and Order ticket—a victory for a more lenient attitude toward Sunday drinking.41

In 1874, the City Council voted to allow saloons to serve liquor on Sundays, as long as the kept their doors closed and windows covered “so as to obstruct the view from such streets into such rooms.”42

However, it remained illegal to under state law to keep a tippling house or a “place where liquor is sold or given away” on Sundays. But Chicago city officials usually ignored that law, much to the consternation of temperance advocates and other people complaining about a general lack of law and order. 43

In 1874, officials renewed sixteen licenses for saloons in Lake View Township, including three near Graceland Cemetery: Daniel Downing’s Sunnyside, Nick Simon’s restaurant, and B. Gindorf’s saloon. Another two saloonkeepers were doing business near Rosehill: Franz Baer and Jacob Hottinger. 44 People often stopped at these places for food and drinks when they buried a loved one or visited a friend’s grave.

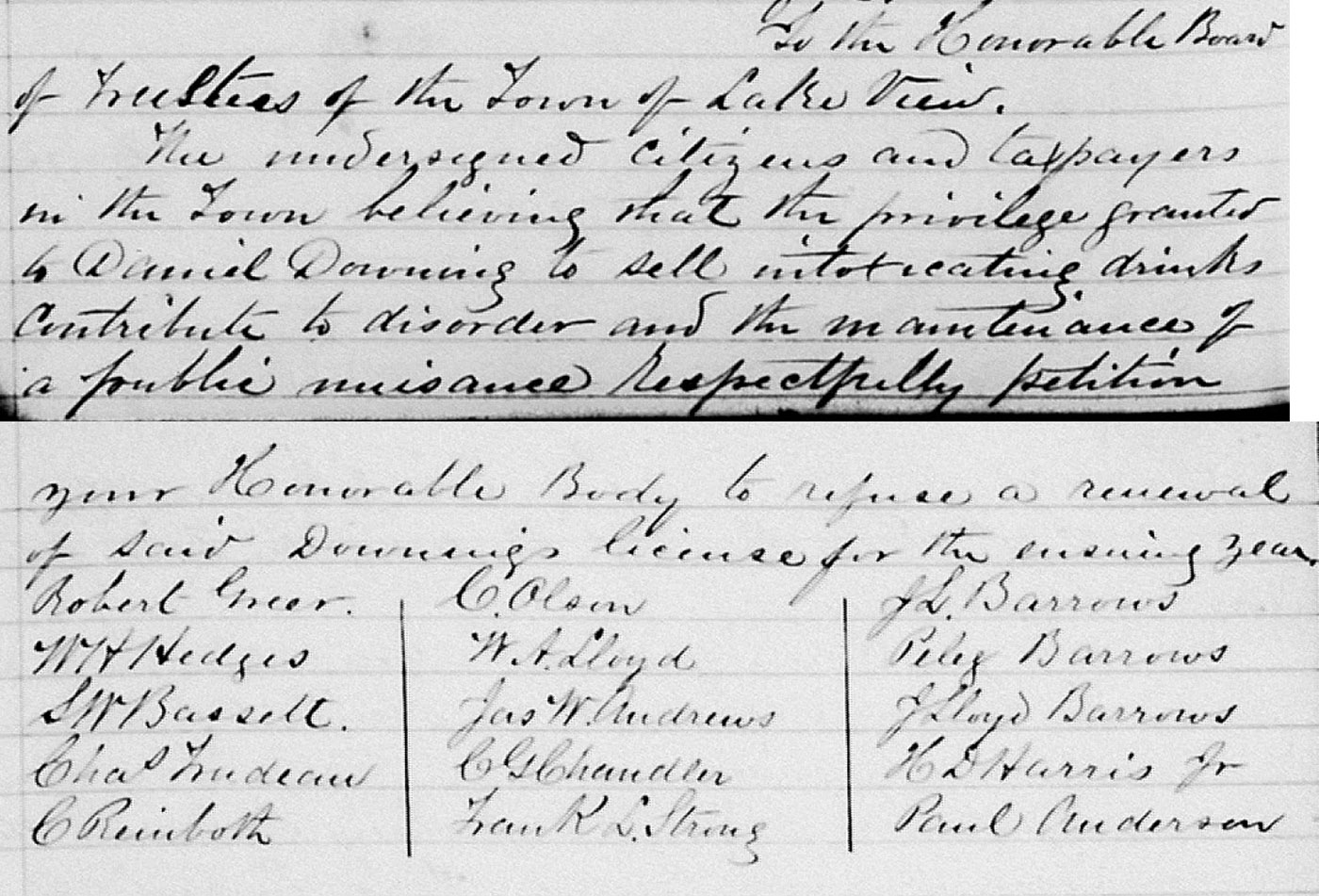

But the township board did not vote right away on Downing’s license application, giving Ravenswood residents more time to complain about the Sunnyside. “The people of that suburb have come to the conclusion that the existence on their borders of this place of resort is not conducive to the moral health of themselves or anybody else, and are upheld in this view by the general sentiment of Lake View,” the Tribune reported.45 Fifteen residents signed a petition:

The undersigned citizens and taxpayers in the Town believing that the privilege granted to Daniel Downing to sell intoxicating drinks contribute to disorder and the maintenance of a public nuisance respectfully petition your Honorable Body to refuse a renewal of said Downing’s license for the ensuring year.

The town trustees voted to postpone their decision so they would have time to “investigate.” 46 Two weeks later, they voted to renew Downing’s saloon license. The meetings of their meeting and the report from the Tribune offer no explanation for why they decided to ignore the complaints.47

An 1879 list of liquor licenses in Lake View Township shows Daniel Downing’s Sunnyside along with four saloons where the location was simply listed as “Graceland.” Those four were owned by Bernard Gindorff, Mrs. Barbara Simon, August Ringele, and Mathias Schweizer. Another four saloons were at Rosehill Cemetery’s gate or nearby. Altogether, Lake View had 26 saloon licenses at the time. 48

The Sunnyside in the news

In 1882, the Sunnyside was featured in a sensational murder trial: It was where Theresa Sturla had dinner with Charles Stiles on the evening before she shot him to death at the Palmer House. She claimed she’d shot him in self-defense, and that he’d been threatening to kill her. Sturla (who was using the alias Madelaine Stiles) told the Inter Ocean about dining at Sunnyside:

“We went upstairs at Downing’s and had a couple of glasses of beer, and also ordered supper. Chicken for two and other eatables were called for, and we were eating them in silence, when finally Charlie said, ‘Do you know I have A NOTION TO KILL YOU?’ I laughed at him and laughed so hard that a chicken bone stuck in my throat. At this juncture Mrs. Downing entered the room, and Charles laughed too, and slapped me on the back. The minute she went out he resumed his fierce air, and took me by the throat. He then said that he had no money to pay for the supper, and I told him not to mind that, I would pay for all that we had eaten.”49

Sophronia Downing testified at Sturla’s trial, saying she hadn’t noticed anything unusual that night.50 A Sunnyside bartender, Monroe Potter, also took the witness stand, but then Daniel Downing testified that he’d fired Potter for drinking excessively on the same night.51 In the end, Sturla was found guilty and sentenced to one year in prison.52

On another occasion, a Chicago Daily News reporter interviewed Daniel Downing for an investigation about road contractors skimping on tar when they surfaced roads, including Clark Street.

“I watched the work carefully and I was surprised to see what a small amount of tar was being used,” Downing told the reporter. “ … It was hardly enough to make a black spot.” The reporter noted that Downing had a “big hearty laugh.”53

Sophronia was also quick to laugh, according to the 1892 book Chicago by Day and Night: The Pleasure Seeker’s Guide to the Paris of America, which described a visit to the Sunnyside. “The hotel itself, kept by the Dowling [sic] family for years, is a great rambling old wooden building standing in the midst of spacious grounds,” the anonymous author wrote.

Supper cost one dollar—but there was no menu. “No orders for special dishes are taken. You can take what is there or go without it. But no one was ever heard to complain of the fare.” According to the author, it was a true farm-to-table operation. The Downings served beef and chicken raised on their land, along with green corn, ripe tomatoes, young onions, and vegetables they’d grown.

The book’s anonymous author rhapsodized about Sophronia Downing (although he misspelled her name):

Dear old Lady Dowling! Venerable high priestess of the quaint old sanctuary of Sunnyside! Many a time and oft, as the writer has heard some merry party of noisy but honest fellows, of whom, alas! he was one, rollout the rare old drinking chorus:

“Then here’s to Mrs. Dowling,

Drink her down! Drink her down!”

has he marvelled at the fewness of the wrinkles upon thy brow considering all that thou hast passed through in thy progress through this earthly vale of tears.

After supper, guests relaxed on the Sunnyside’s wide verandah, where they might include “a party of frolicsome youths who have driven out on a six-horse tally-ho, and who have brought their mandolins and guitars along.” The book described how “their songs and laughter fall pleasantly upon the balmy air.”54

(Northwestern University Press published an annotated edition of Chicago by Day and Night, edited by Paul Durica and Bill Savage, in 2013.)

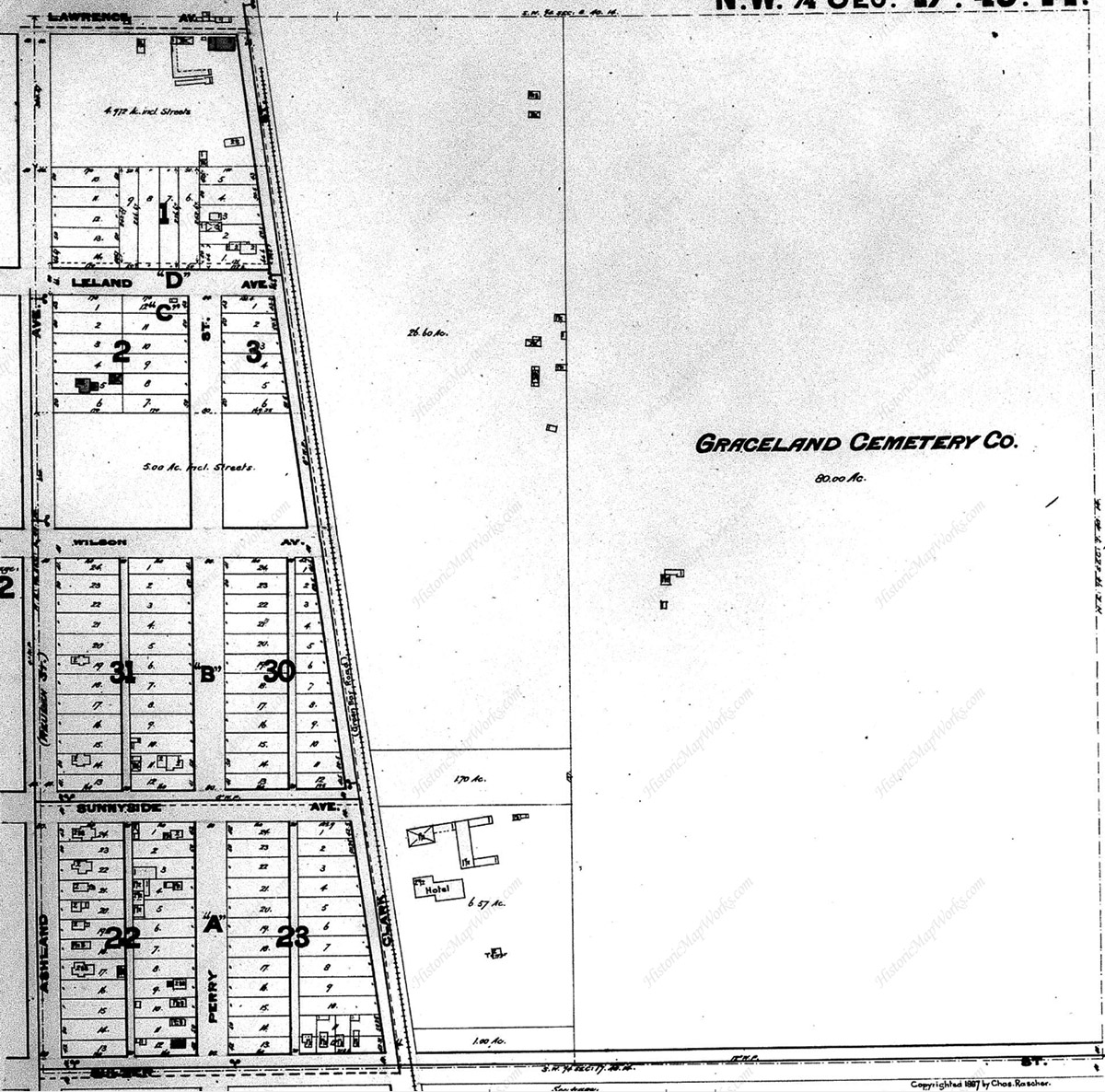

An 1887 map of Lake View Township (available at Historic Map Works) shows the Sunnyside standing alone on seven and a half acres, with a large swath of open land east of it—which was owned at the time by Graceland Cemetery. (The cemetery’s owners would subdivide that land and sell it off in 1891, initially calling it the Sheridan Drive Subdivision, though it would soon be known as Sheridan Park.55) As of 1887, most of the lots along on the east side of Clark Street were still vacant, too.56

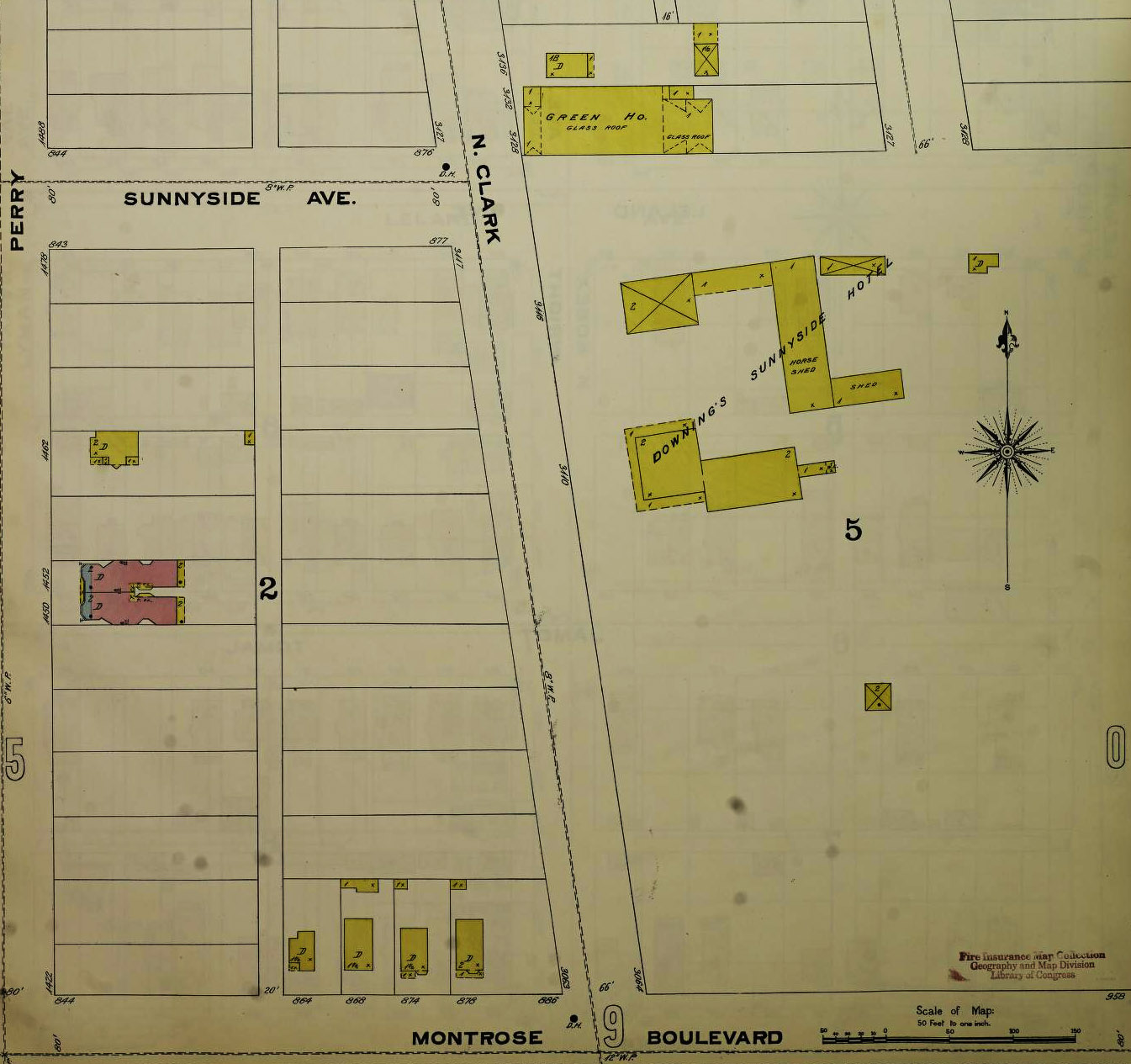

Another diagram of Downing’s Sunnyside Hotel appears on an 1894 Sanborn-Perris fire insurance map.57 The Sunnyside property extended the equivalent of a block and half east from Clark Street. The hotel’s buildings were closer to the north end of the block, roughly where the Japanese American Services Committee is today.

On the map, the main hotel building looks like three rectangles stuck together, with a footprint covering roughly 7,200 square feet. North of it, a horse shed and other buildings covered around 9,900 square feet. Note how Sunnyside Avenue did not run through on the east side of Clark Street at that time. (It would be extended east of Clark Street in 1895.58) A greenhouse with a glass roof was just north of the hotel. Most of the surrounding property was vacant.

Cemetery saloons

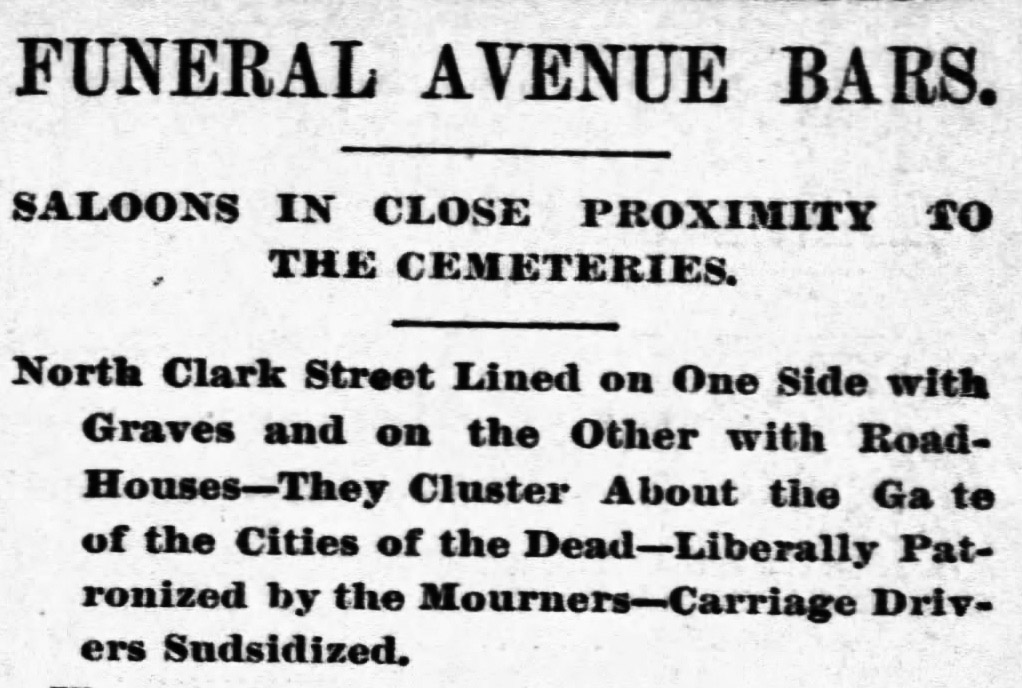

By this time, the Sunnyside was one of many roadhouses, picnic groves, and beer gardens amid the cemeteries along Clark Street. Some neighbors complained about these “cemetery saloons.”

“There are many people to whom the mere presence of these resorts in such obnoxious proximity to the graves of the loved ones who have passed away and been laid to rest in the city of the dead is intolerable,” the Tribune wrote in 1890, observing “an endless procession” of hearses on Clark Street on Sundays.

According to the Tribune, hearse drivers often led an entire funeral procession to a saloon. In return, a saloon would give a hearse driver “all the whiskey he wants in return for ‘steering’ the mourners to these places.”59

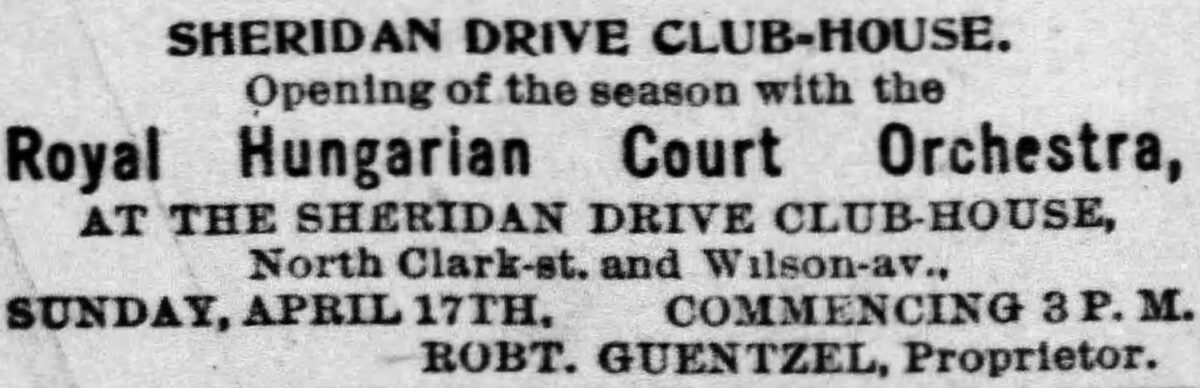

The “resorts” on Clark Street also included the Sheridan Drive Club House at the southwest corner of Clark and Wilson Avenue (where the Issel Building, constructed in 1929, now stands). In 1894, the Inter Ocean called it “a gambling den in which both men and women woo the goddess of fortune.”

Run by Leopold Nathan, this “palace dedicated to feminine gamesters” had roulette wheels upstairs, along with faro and stud poker games. “Many of the fair customers are persons well known to society. At no stage of its existence has the Sheridan Drive Club opened its doors to loose characters.”

The Inter Ocean expressed shock that this gambling was taking place so close to Graceland Cemetery: “Drinks are supplied lavishly, and within the shadow of the resting-place of the dead the debasement of the living goes on.”60

The Sheridan Drive Club House also held horse and sleigh races along Wilson Avenue on snowy winter days.61 By 1896, W.J. McGarigle had taken over as the proprietor, calling it “The Finest Equipped Road House in the West.”62

That same year, he presided when his clubhouse was the starting point for the Germania Riding Club’s fox hunt through the nearby Ravenswood countryside.

The Humane Society protested, insisting that the event should use a dead fox rather than a live one. And so, the organizers brought a captive fox and hit it with a hatchet. Then a horse dragged the “half-dead” fox away, and the hounds followed the fox’s scent. The event ended with a dispute over who’d won.63

Another drinking spot was the Manila Grove64 or Manila Garden, on the west side of Clark Street at Leland Avenue (across from where Carol’s Pub is today). Simon’s Grove was a bit farther north: a dancing pavilion, saloon and bowling alley southwest of Clark and Lawrence, kitty-corner from St. Boniface Cemetery.

North of that, another saloon stood across from the entrance to St. Boniface (a.k.a. St. Bonifacius), with a restaurant, bar, bowling alley, and sheds. Flanked by two businesses that made tombstones and monuments, this cemetery saloon was at the site where Rainbo Gardens later became one of the city’s most prominent cabarets. 65

Jacob Keil, who bought the land in 1883 and 1884,66 may have been the saloon’s original owner. He received a saloon license from Lake View Township on August 11, 1885.67 Keil was also the cemetery’s superintendent.

The Chicago Daily Tribune reported that “he did a thriving business; funerals helped in their own little way. Mourners did not disdain at times to drown a portion of their sorrows in the amber glass.”68 The saloon appears on the 1887 map from Historic Map Works.69

In 1888, Keil was sued by Paul C. Thelle, whom he employed as both a bartender and a gravedigger. The Tribune described Thelle as a “a rubicund and good-natured Luxemburger.” Thelle complained it was difficult to switch back and forth between digging graves and pouring beer. “He had to drop the shovel for the spigot too many times in the course of the day to suit his fancy.”

A lawyer’s questions in the trial give us a picture of what this roadhouse was like: “And the saloon did a good business, didn’t it; and the beer was plentiful, eh? And Limburger cheese, and sausages, and all that sort of thing, eh?”

Keil was paying his bartender-gravedigger $15 a week plus one glass of beer per day. The jury ruled in favor of Paul Thelle, saying he should have been paid $25 weekly—including an extra $10 for digging graves. The jury awarded him $137 in back pay. The Tribune’s illustrator offered this suggestion for how Thelle might do both of his jobs more efficiently.70

Keil sold the saloon property in 1890 to Anthony Iten.71 August Biewer bought it in 1894,72 and it became known as Biewer’s Garden.73

The Sunnyside Inn’s patriarch, Daniel Downing, died in 1892.74 The Reverend J.P. Brushingham spoke during his funeral at the Sunnyside, saying Downing “had always been an affectionate father, a devoted husband and an exemplary citizen.”75 Sophronia Downing died two years later. They’re both buried at Rosehill Cemetery.76

Back in 1867, their daughter Clara had married Parker Mason, a well-known Chicago distiller.77 And now the Sunnyside was taken over by one of the Downings’ grandchildren—Clara and Parker’s son William Mason78—but not without some controversy.

William’s 17-year-old sister Angeline eloped with a 28-year-old Sunnyside waiter, “a good-looking man” named either Edward or William H. Jones, who took her to Montreal. Jones was accused of abducting this “heiress” to get his hands on the family’s money. (However, Angeline wasn’t actually named in Sophronia’s will, which named her grandchildren William Mason and Clara E. Steele—Angeline’s sister—as the heirs of her personal estate.79) When Jones returned to Chicago, he was charged with abduction and bigamy, since he had one or possibly two other wives.80

It’s unknown what exactly happened as the result of this affair, but it was the subject of much gossip in Ravenswood. “Everybody who knows anything about Ravenswood knows something about the Sunnyside hotel,” the Chicago Daily News remarked. “The old settlers up in that part of the city knew ‘Dan’ Downing and they know Parker Mason. That is the reason Miss Mason’s elopement created so much stir.”81

More controversy surfaced when Parker Mason filed a lawsuit, alleging that he’d been cheated out of a share in the Sunnyside’s property. He accused two of his children—William Mason and Clara E. Steele—of forging his signature on a quit-claim document giving up his half-ownership of the property.82 But Parker Mason died two months after he sued,83 and it’s unknown whether his allegations were true.

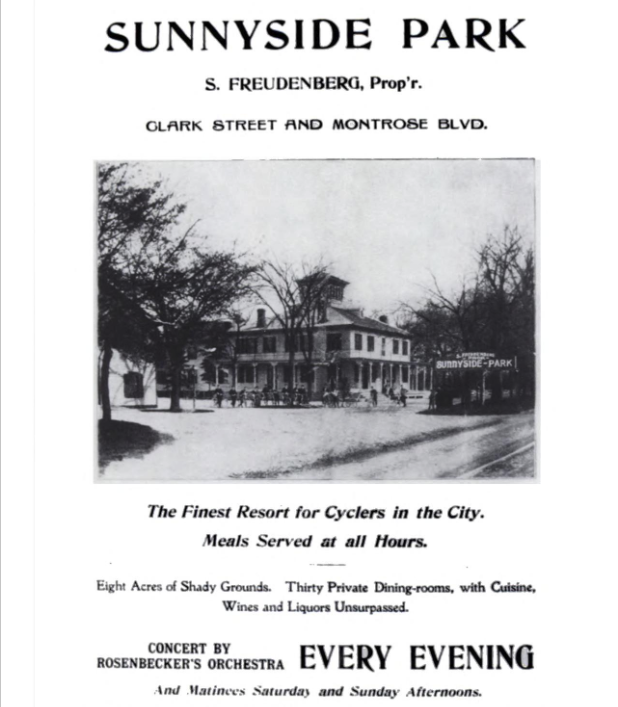

An outdoor concert venue

The Sunnyside entered a new era under William Mason’s management. In 1895, it began advertising outdoor concerts, with seating for eight thousand.84

When I researched my Curious City story on the history of entertainment in the Uptown neighborhood, this was the oldest example I found of any concerts being publicized in the area that later became Uptown. Surely, there were other musical performances in earlier times, but the mid-1890s seems to be the era when they were advertised for the first time.

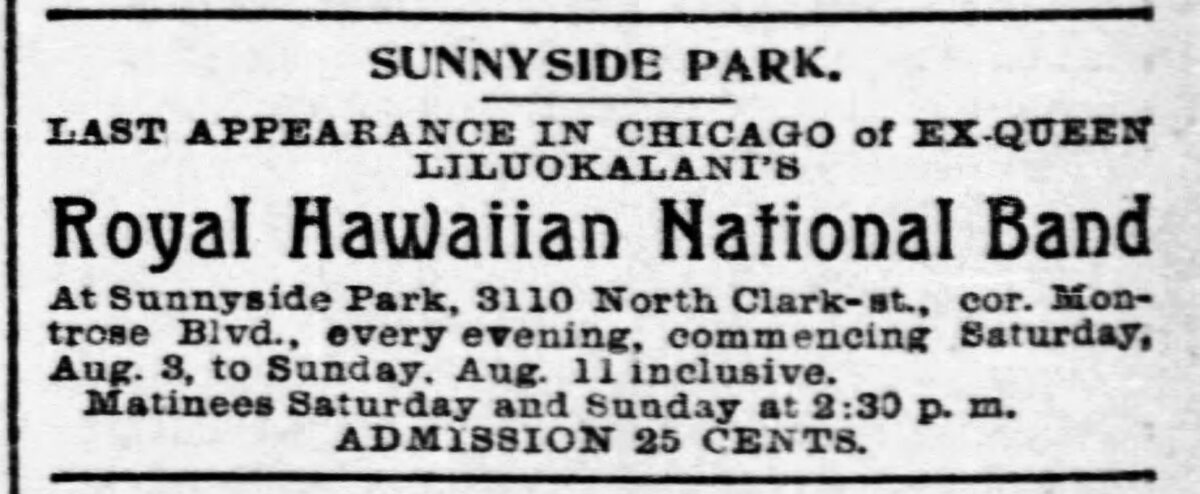

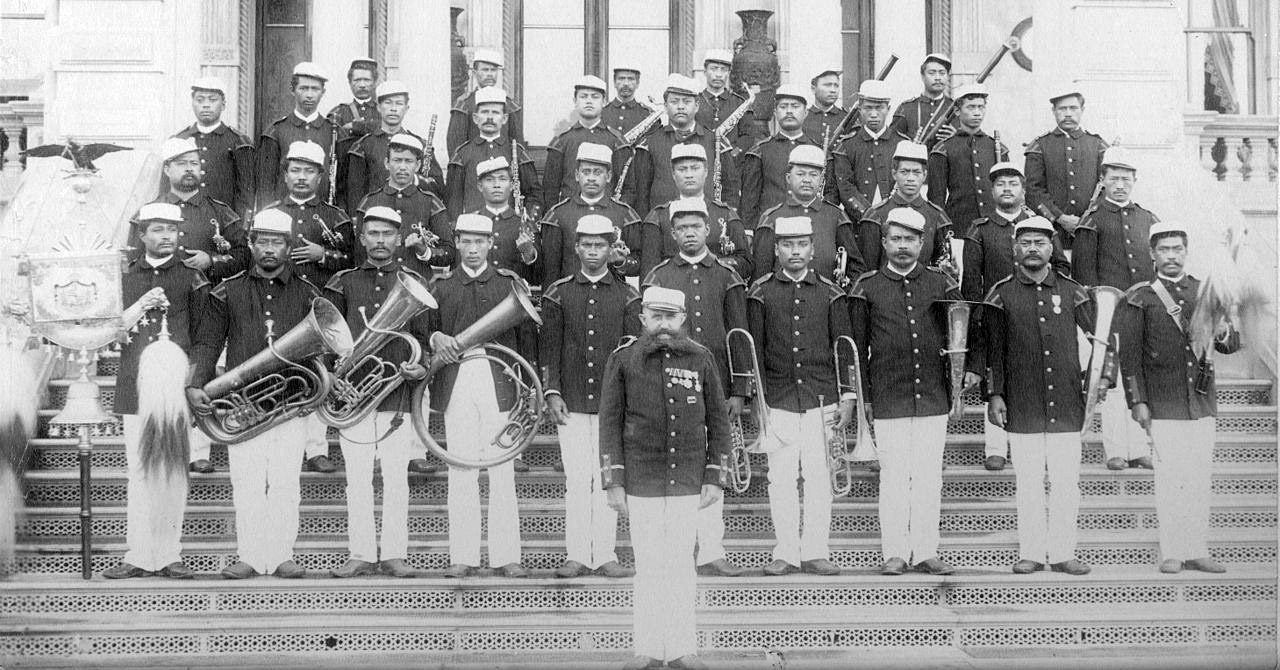

Performers at the Sunnyside included the Royal Hawaiian National Band,85 German86 and Swedish choirs,87 opera troupes,88 military bands,89 and an orchestra conducted by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s Adolph Rosenbecker.90

As the Sunnyside became more of a concert venue, the Sheridan Drive Club-House also hosted musical performances, advertising shows by the Royal Hungarian Court Orchestra.91

The Sunnyside added vaudeville shows in 1897 after building a new performance structure “at a considerable cost.” The Tribune commented: “The stage is as large as anything in the city, and the change to the vaudeville from the concerts of last year will be a welcome one to patrons of amusements who find in the vaudeville a more entertaining kind of performance, especially for an al fresco one, of any kind yet presented.”92

This was the era when bicycle riding was booming in popularity, and one Sunnyside Park advertisement noted, “Bicycles checked free.”93 And the Tribune observed: “The park lies directly in the path of the cyclers, who throng the North Side boulevards, while the Clark street cars on the electric line pass by the door.”94 (Read my Chicago Tribune story “In 1890s Chicago, bicycles were all the rage.”)

Motion pictures—including one described as “the Spanish Bull Fight”95—were shown at Sunnyside in 1899 with a device advertised as the “Justoscope.”96

On Twitter, I asked filmmaker and writer Michael Glover Smith whether he knew anything about this early movie-projection machine. Smith (who co-wrote Flickering Empire: How Chicago Invented the U.S. Film Industry with Adam Selzer) replied: “Never heard of the Justoscope but that’s intriguing! A lot of people patented movie projectors around that time and many of the names ended in ‘scope’ (e.g., Mutoscope, Phantoscope and Magniscope, the last of which was invented by Edward Amet of Waukegan).”97

Perhaps the biggest crowd in the history of Sunnyside Park—an estimated forty thousand people—filled the grounds on September 3, 1899, to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s birth, watching a performance by some 2,000 singers and musicians.98 The Tribune described the elaborate decorations for this event:

The entrance in North Clark Street has been built up in the design of a medieval portal. In the center is a large painting of Goethe, draped with United States and German flags, so mingled that no precedence is given to either. From the gateway and arched colonnade leads to the pavilion. Each pillar is decorated with a shield—on one hand a German shield draped with American flags, on the other an American shield draped with flags of the empire. On each shield is an inscription from the works of Goethe. Throughout the grounds the trees bear similar shields.

The stage presents the likeness of a Greek temple. Apart from it a stand has been erected to seat 1,500 singers, from which will float consular flags loaned by representatives of various governments in Chicago. A special guard of sixteen men has been appointed to watch these banners. All nations are honored in the festival, because the Germans believe Goethe wrote for the world rather than for one nation.99

This event aimed to raise money for a statue of Goethe in Lincoln Park.100 Herman Hahn’s sculpture of Goethe would be installed in 1911 in the park, where it still stands today.101

This event aimed to raise money for a statue of Goethe in Lincoln Park.100 Herman Hahn’s sculpture of Goethe would be installed in 1911 in the park, where it still stands today.101

In 1899, local residents complained about “disreputable resorts” serving alcohol on Sundays, including Sunnyside Park, Sheridan Park Club House, Manila Garden, Simon’s Grove, Biewer’s Garden, and a place called Shadyside.102 (According to Lyden’s book, Shadyside was the Sunnyside’s “alter ego establishment,” located across the street from it. “The Shadyside supposedly catered to a much less genteel clientele,” she wrote.103)

The Sunnyside’s John H. Colvin called the protesters hypocrites. “Last year 100,000 people visited our place and church picnics were held there. I would have told them that they were condemning their own people,” he said.104

In 1900, the Sunnyside’s advertisements proclaimed: “All Roads Lead to Sunnyside Park.”105 But the company dissolved in 1901.106 The park continued operating the following year under a new name, Mason Park,107 but its days were numbered. It soon shut down, and the property was subdivided in 1903, officially known on county property documents as the Sunnyside Addition to Sheridan Park.108

Today, the only remnant of the Sunnyside Inn is the street named after it. 109

Read the next chapter: The Early Years of Green Mill Founder Tom Chamales

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Footnotes

1 Jacki Lyden, Landmarks and Legends of Uptown (Chicago: Jacki Lyden, 1980), 71.

2 The Rosehill & Evanston Road Co. V. People ex rel. W.N. Lawless, 115 Ill. 133, in Homer C. Irish, ed., The American Corporation Cases, Vol. X: Private Corporations (Chicago: E.B. Myers & Company, 1887), 276-279. https://books.google.com/books?id=xoy1AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA276.

3 Martin Tangora, email to author, February 26, 2023.

4 “Passing of Old Chicago Resort,” Inter Ocean, May 10, 1903.

5 Author’s analysis of U.S. census, 1860, Lake View Township, Cook County, Illinois, at Ancestry.com.

6 “Passing of Old Chicago Resort,” Inter Ocean, May 10, 1903.

7 Survey of Green Bay Road, October 7 and 8, 1857, Board of Trustees of the Town of Lake View, Minutes, 32-33, Illinois Regional Archive Depository, Northeastern Illinois University.

8 W. L. Flower and Edward Mendel, Map of Cook County, Illinois (Chicago: S. H. Burhans & J. Van Vechten, 1861), Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4103c.la000104/?r=0.635,0.32,0.055,0.034,0

9 Patricia Mooney-Melvin, “Rogers Park,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1086.html.

10 John J. Flinn, History of the Chicago Police From the Settlement of the Community to the Present Time. (Chicago: Police Book Fund, 1887), 104, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiuo.ark:/13960/t48p5wz8b&view=1up&seq=170.

11 Gerald R. Gems, Sport and the Shaping of Civic Identity in Chicago (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2020), 6. https://books.google.com/books?id=WKrNDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA6; “Another Assault on a Gambler,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 24, 1866, 4.

12 Advertisement, Chicago Times, December 12, 1866, 5.

13 “An Opening Dance,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Dec. 20, 1866, p. 3.

14 “The Sunnyside ‘Riot,’” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 3, 1867, 4.

15 “Passing of Old Chicago Resort,” Inter Ocean, May 10, 1903.

16 “Pugilists in Trouble,” Chicago Republican, December 19, 1867, 8.

17 “Brutal Outrage Upon a Woman,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 19, 1867, 4.

18 Advertisement, Chicago Republican, September 9, 1867, 8.

19 “The Great Steeple-Chase,” Chicago Republican, August 14, 1867, 5.

20 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, August 11, 1867, 4.

21 “The Great Steeple-Chase,” Chicago Republican, August 14, 1867, 5.

22 Advertisement, Chicago Republican, March 11, 1869, 4. The same ad also appeared on March 12 and 27.

23 “Ravenswood,” Chicago Evening Post, May 3, 1869, 4.

24 Caroline M. M’Ilvaine, “Historical Spots in Chicago: Ravenswood,” Chicago Daily News, September 30, 1927, 37.

25 Robert Ridgway, The Ornithology of Illinois, Vol. I, Part I: Descriptive Catalogue (Springfield, IL: H. W. Rokker, 1889), 331, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044062425335?urlappend=%3Bseq=349%3Bownerid=27021597765954997-375; Robert Ridgway, Catalogue of the Birds Ascertained to Occur in Illinois (from the Annals of the Lyceum of Natural History, New York, vol. x, January 1874), 375, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112001915914?urlappend=%3Bseq=27%3Bownerid=113433693-31; Benjamin True Gault, Check List of the Birds of Illinois (Chicago: Illinois Audubon Society, 1922), 61, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015065413711?urlappend=%3Bseq=63%3Bownerid=13510798885698622-67.

26 “What’s the Difference?: Crow vs. Raven,” The Buzz, Forest Preserve of Will County, January 19, 2022, https://www.reconnectwithnature.org/news-events/the-buzz/what-s-the-difference-crow-vs-raven/.

27 Chicago Department of Transportation, “The Chicago 80 Acre Map Library,” accessed March 20, 2023, https://gisapps.chicago.gov/KioskMap/; Tract Book 545, 2E, 2G, 2I, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

28 “Suburban News: Lake View,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 22, 1874, 2.

29 Advertisement, Chicago Republican, April 10, 1869, 1.

30 “Chicago Streets,” Chicago History Museum, http://chsmedia.org/househistory/nameChanges/start.pdf.

31 “Ravenswood,” Chicago Evening Post, May 3, 1869, 4.

32 Mistakenly calling him George Downing, the Inter Ocean said he took ownership in 1869. “Passing of Old Chicago Resort,” Inter Ocean, May 10, 1903.

33 Vermont, U.S., Vital Records, 1720-1908, Ancestry.com.

34 1860 U.S. Census, Illinois, Cook County, West Chicago Township, 174, Ancestry.com.

35 1870 U.S. Census, Illinois, Cook, Jefferson, 1, Ancestry.com.

36 “Old Inn Girded by Forest Recalled at Ravenswood,” Chicago Daily News, April 6, 1940, 10.

37 “Passing of Old Chicago Resort,” Inter Ocean, May 10, 1903.

38 “A Dry Day,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Oct. 21, 1872, p. 8.

39 Lloyd Lewis and Henry Justin Smith, Chicago: The History of Its Reputation (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1929), 148, https://archive.org/details/chicagothehistor013789mbp.

40 “Plain Talk From Medill,” Chicago Evening Post, October 3, 1872, 1.

41 Karen Sawislak, Smoldering City: Chicagoans and the Great Fire, 1871-1874 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 234-235, 237, 256.

42 City advertisement, Inter Ocean, March 21, 1874, 7.

43 Harvey B. Hurd, ed. and comp., The Revised Statutes of the State of Illinois, 1901 (Chicago: Chicago Legal News Company, 1901), chapter 38 § 259, 638, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.35112105473971?urlappend=%3Bseq=670%3Bownerid=13510798902240829-694.

44 “Suburban News: Lake View,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 10, 1874, 8; “Lake View,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 8, 1874, 3.

45 “Suburban News: Lake View,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 10, 1874, 3.

46 July 6, 1874, minutes, Board of Trustees of the Town of Lake View, 310-311.

47 July 20, 1874, minutes, Board of Trustees of the Town of Lake View, 320; “Suburban News: Lake View,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 22, 1874, 2.

48 Lake View Saloon and Plumber Licenses, 1879–1890, Illinois Regional Archives Depository, Northeastern Illinois University.

49 “The Wages of Sin,” Daily Inter Ocean, July 11, 1882, 5.

50 “The Sturla Trial,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 28, 1882, 6.

51 “The Sturla Trial,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 29, 1882, 7.

52 Case 2132, Homicide In Chicago 1870-1930, https://homicide.northwestern.edu/database/2110/; “Theresa Sturla Sentenced,” (Little Rock) Arkansas Gazette, December 24, 1882, 4.

53 “No More Tar Steals,” Chicago Daily News, February 2, 1888, 6.

54 Chicago by Day and Night: The Pleasure Seeker’s Guide to the Paris of America (Chicago: Thomson and Zimmerman, 1892), 172-175, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiuo.ark:/13960/t0bv7dj3r?urlappend=%3Bseq=174.

55 Tract Book 587B, 3, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

56 Charles Rascher, Rascher’s Atlas of Lake View Twp., Cook Co. Ill. (Chicago: Charles Rascher, 1887), Sheet 27, accessed March 2, 2023, http://www.historicmapworks.com.

57 Chicago, Vol. A (Sanborn-Perris Map Company, 1894), https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4104cm.g017901894A/?sp=19&r=-0.051,0.268,1.138,0.751,0.

58 Original Map Index 13, 82, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

59 “Funeral Avenue Bars,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 6, 1890, p. 7.

60 “Women Who Gamble,” Inter Ocean, April 19, 1894.

61 “J.F.R. Wins the Sleigh Race,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 17, 1895, 5; “Snow Still Holds Out,” Inter Ocean, Feb. 25, 1896.

62 Advertisement, Chicago Eagle, March 7, 1896.

63 “Use an Ax on the Fox,” Inter Ocean, December 20, 1896, p. 1.

64 “Irish Club Picnic,” Inter Ocean, June 18, 1899.

65 “Bowmanville,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 26, 1890, p. 14.

66 Tract Book 541B, 267, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

67 Lake View Saloon and Plumber Licenses, 1879–1890, Illinois Regional Archives Depository, Northeastern Illinois University.

68 “A Happy Combination,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 27, 1888.

69 Charles Rascher, Rascher’s Atlas of Lake View Twp., Cook Co. Ill. (Chicago: Charles Rascher, 1887), Sheet 37, accessed March 2, 2023, http://www.historicmapworks.com.

70 “A Happy Combination,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 27, 1888.

71 “Bowmanville,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 26, 1890, p. 14.

72 Tract Book 541B, 267, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

73 “French to Hold a Fete,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 8, 1900.

74 Cook County, Illinois, U.S., Deaths Index, 1878-1922, Ancestry.com.

75 “Daniel Downing’s Funeral,” Chicago Daily News, October 10, 1892, 1.

76 Cook County, Illinois, U.S., Deaths Index, 1878-1922, Ancestry.com.

77 Illinois, U.S., Marriage Index, 1860-1920, Ancestry.com.

78 “Indicted for Bigamy,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 25, 1894; “Passing of Old Chicago Resort,” Inter Ocean, May 10, 1903.

79 Illinois, Wills and Probate Records, 1772-1999, Ancestry.com.

80 “Ran Away With an Heiress,” Inter Ocean, September 11, 1894, 3; “Ran Off With Angeline,” Chicago Daily News, September 19, 1894, 1; “E.H. Jones Indicted for Bigamy,” Inter Ocean, September 25, 1894, 8.

81 “Mum About Miss Mason,” Chicago Daily News, September 19, 1894, 1.

82 “Ill and Fears Forgery,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 8, 1899, p. 1.

83 Cook County, Illinois, U.S., Deaths Index, 1878-1922, Ancestry.com.

84 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, August 13, 1899.

85 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, August 3, 1895.

86 “Mannerchor at Sunnyside Park,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 19, 1896.

87 “Bellman Annual Festival,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 24, 1898, p. 10.

88 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, August 25, 1901.

89 Advertisement, Inter Ocean, August 18, 1895.

90 “Orchestral Music out of Doors,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 14, 1896.

91 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, April 17, 1898.

92 “The Theaters: Notes,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 23, 1897, p. 28.

93 Advertisement, Inter Ocean, May 29, 1896.

94 “The Drama: Notes,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 6, 1897, p. 36.

95 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, September 3, 1899, p. 36.

96 Advertisement, Inter Ocean, July 2, 1899.

97 Michael Glover Smith (@whitecitycinema) tweet, March 28, 2020, 3:42 p.m., https://twitter.com/whitecitycinema/status/1244001968592424960?s=20.

98 “Honor Goethe in Fete,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 4, 1899, p. 5.

99 “Goethe’s Day of Honor,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 3, 1899, p. 8.

100 “The Goethe Festival,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 24, 1899.

101 “Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Monument,” Chicago Park District, accessed March 1, 2023, https://www.chicagoparkdistrict.com/index.php/parks-facilities/johann-wolfgang-von-goethe-monument.

102 “Plan a War on Resorts,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 5, 1899; “To Fight Beer Gardens,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 10, 1899, 10.

103 Lyden, Landmarks and Legends of Uptown, 71.

104 “To Fight Beer Gardens,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 10, 1899, 10.

105 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 3, 1900.

106 “Sunnyside Park Company in Hands of a Receiver,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 17, 1901.

107 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, May 19, 1902.

108 “Sunnyside Park to be Subdivided,” Inter Ocean, April 17, 1903; Plat 3373799, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

109 “Chicago Streets,” Chicago History Museum, http://chsmedia.org/househistory/nameChanges/start.pdf.