Chapter 3 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

The land in Chicago looks flat. There are no mountains on the horizon. And when you go around the city, you might not notice any hills. But there are some areas where the land is slightly elevated. The Uptown neighborhood was shaped by this topography.

It explains why major roads like Clark Street are where they are. Cemeteries were established at places where the ground is higher. Roadhouses and saloons opened nearby, serving travelers as well as parties of mourners visiting the graveyards. Over time, some of those saloons became concert venues, planting the seeds of what became Uptown’s entertainment district in the early 20th century.

As Harold Henderson put it in his insightful 2007 Chicago Reader story about the neighborhood: “A few fateful feet of elevation set the Uptown story in motion.”1

An ancient sandbar

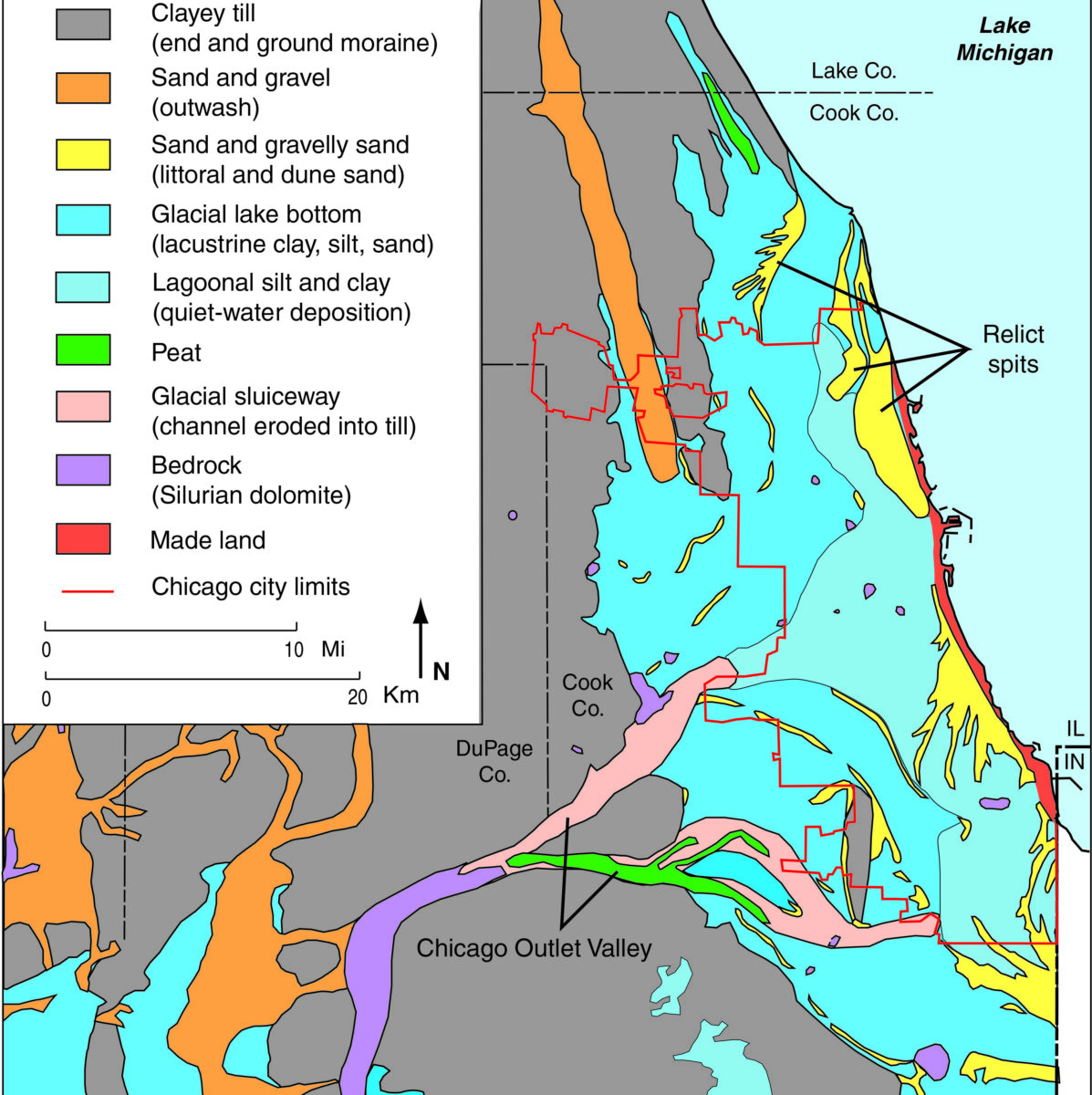

The landscape in Uptown (and the rest of Chicago) was shaped by the melting of glaciers thousands of years ago. The melting ice enlarged Lake Michigan, creating a body of water that geologists call Lake Chicago. About 12,500 years ago, water covered all of the land where the city is today.2

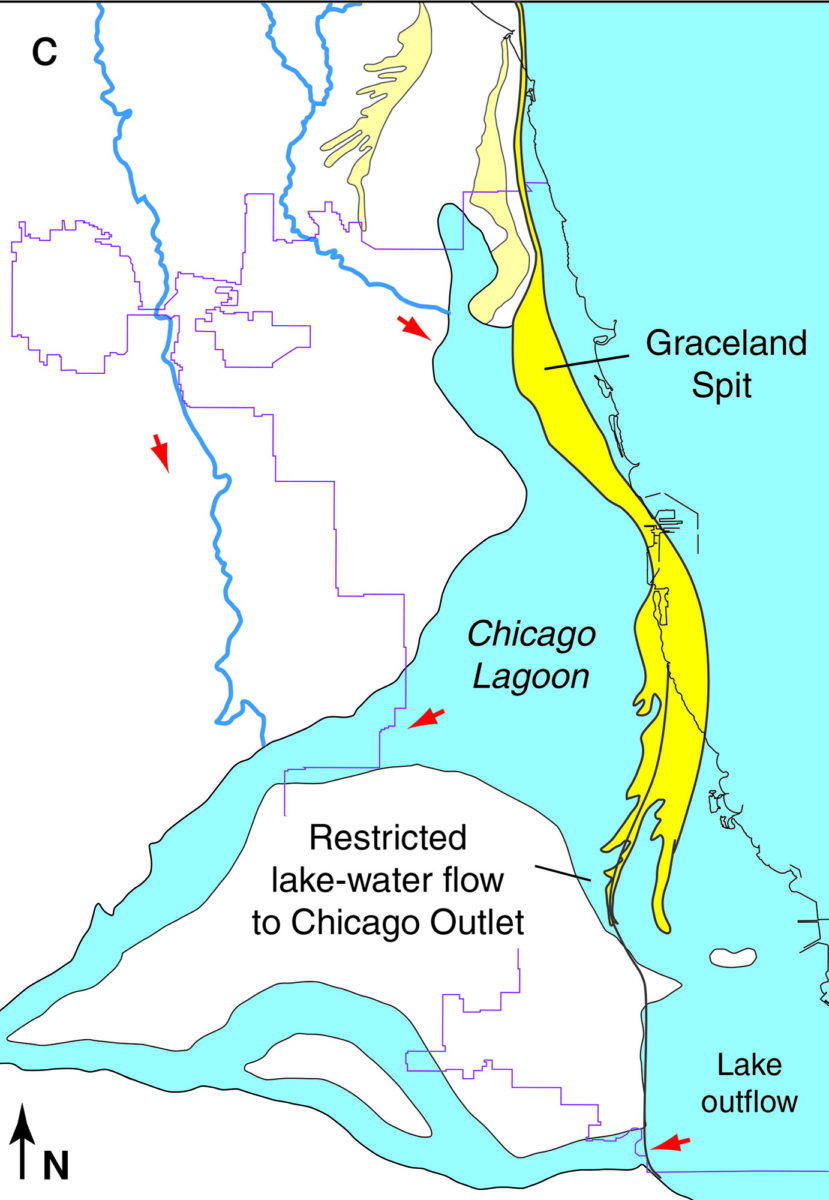

Over time, the lake’s water rose and fell, and the contours of the land around it changed. During one era when the lake was smaller—around 10,000 years ago—a river ran into the lake around the spot where Montrose Harbor is today. In a presentation for the Illinois State Geological Survey, geologist Michael J. Chrzastowski calls this river the “ancestral North Branch.”

Around 5,800 years ago, sand and gravel formed a spit of land around the spot where Graceland Cemetery is now.

I imagine this was something similar to the sand you can see building up today at places along Lake Michigan’s shores. Most famously, the Indiana Dunes at the lake’s southern end are formed by sand carried south by the water. Sand also piles up along Chicago’s shore when it runs into rocks or manmade objects.

Over the past few years, I’ve observed how sand has accumulated along the north edge of pier at Montrose Beach—and then, as the water rose and began flowing across the sand, it formed a little cliff: a miniature version of the changes this region went through thousands of years ago.

The ancient spit of sand near Graceland Cemetery’s location was a sort of peninsula. This finger of sand extended south, with water on either side of it—the lake to the east, and a vast lagoon to the west.

Geologists studying prehistoric Chicago called this the Graceland Spit, naming it after the cemetery. But it actually extended far beyond the present-day cemetery location—stretching south for nearly 17 miles.

When the lake eventually shrank, turning into the Lake Michigan that we now today, the Graceland Spit became a feature of Chicago’s topography—an elevated ridge of sandy ground.

This ridge was a barrier for the water in the “ancestral North Branch,” preventing this river from flowing east toward its former mouth near the site of Montrose Harbor. Instead, the water went south, where it eventually formed the Chicago River’s famous Y-shaped conjunction.3

Indigenous tales

Indians may well have been living around the site of modern-day Chicago as the land and water went through all of these massive changes, though it’s uncertain which tribes were in this vicinity. Archaeological research shows that Native Americans had arrived in North America some 30,000 years ago.4

Like many peoples around the world, North America’s Indigenous people have ancient stories about great floods, or of the world emerging out of water.

“Our creation stories tell us that there was a great flood—that the world essentially emerged then on the back of a turtle,” Potawatomi historian John N. Low told me when I interviewed him in 2021 for WBEZ’s Curious City. And that’s why the Potawatomi, who lived around Lake Michigan in the era when Europeans arrived, referred to their world as “turtle island,” Low said. (Low writes about these stories in his 2016 book Imprints: The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians and the City of Chicago.)

In another Potawatomi story, the world is covered with water. A man floats in a canoe, crying. A muskrat tells him, “But there is earth under all this water!” The muskrat helps the man by diving down into the water and bringing up some mud. Working together with the other animal chiefs, they form the land. The Ojibwe, another tribe in this region, had a similar story.5

Today’s topography

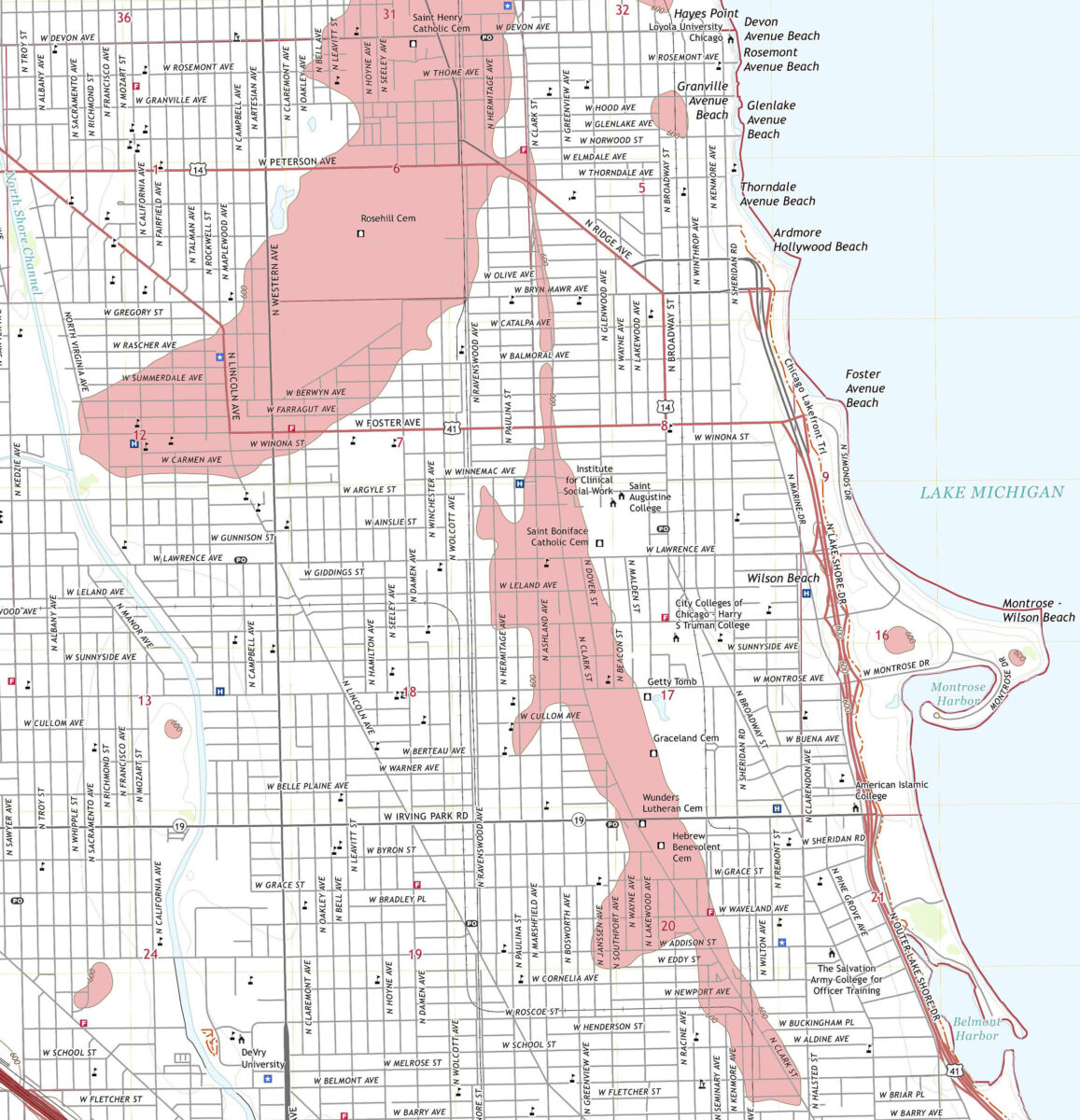

In this 2021 map by the U.S. Geological Survey, I’ve colored in the areas with an elevation of 600 feet above sea level or higher:

You can see the Graceland Spit as well another sandy ridge to the north. That’s the Rose Hill Spit, which also happens to be named after a cemetery.6 The colored areas have an elevation of 600 to 610 feet; most of the surrounding white areas are 590 to 600 feet above sea level. In most of Chicago, the elevation is around 595.7 (You can use the U.S. Geological Survey’s topoView website to find topographical maps made at various times for any location in the country.)

These rises in Chicago’s topography are visible if you look hard enough. If you’re heading west on Montrose Avenue north of Graceland Cemetery, note how the road slopes upward as it approaches Clark Street.

Walking through Graceland, you’ll see many little hills. The land is noticeably lower at the eastern ends of Graceland and St. Boniface Cemetery.

Along the east side of Dover Street—a block east of Clark Street—some of the front yards rise up a few feet from the street.

Native Americans used the Graceland Spit and other similar topographic features as trails. According to a 1999 Edgewater Scrapbook article by Ray Noesen, “these sandy strips were the only well-drained ground in the spring, and the Indians used them for overland travel when the surrounding area was water logged.”

When white settlers came to the region, they also used these rises in the land. The trail along the Graceland Spit was part of a route connecting trading posts in Chicago and Green Bay, Wisconsin.8

The Green Bay Trail appears on a map of local Native American trails as they existed in 1804, published in 1900 by historian Albert F. Scharf.9 As early as 1825, the United States used it to carry mail between military forts.10 (By this time, the U.S. government and the region’s white settlers were coercing Native Americans to sign treaties abandoning their homelands around Chicago.)

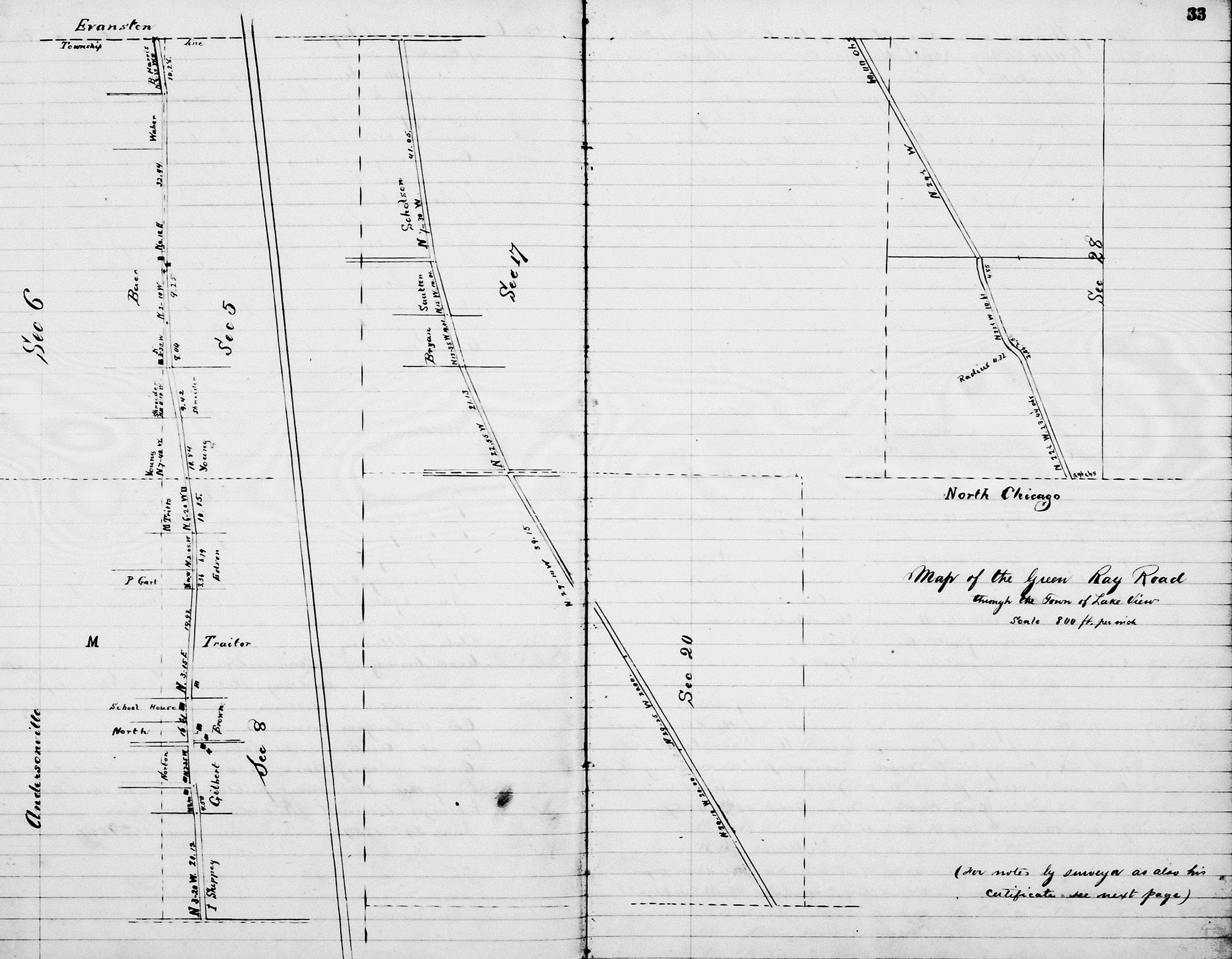

In this era, the trail became known as Green Bay Road. (The portion of the road running through Lake View and Uptown is now called Clark Street.)

According to historian A.T. Andreas, Green Bay Road was surveyed in 1833, with “stakes driven and trees blazed along the line.” He continued: “It was somewhat improved as far as Milwaukee in 1834 by laying puncheon and log bridges over the unfordable creeks and streams and cutting out the trees to the width of two rods [33 feet]. No grading was done for years afterward …”11

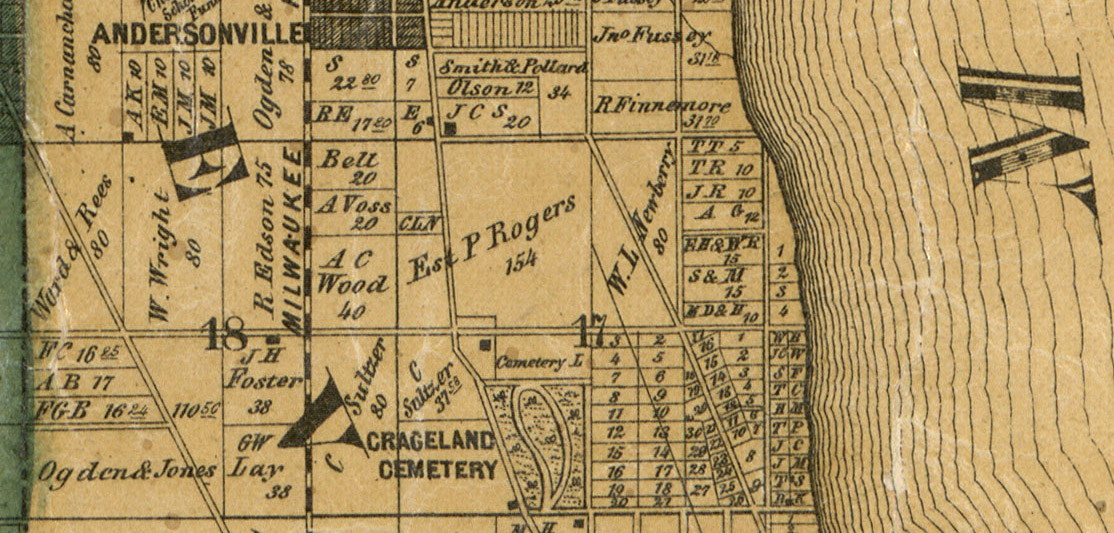

A map by the U.S. surveyor general’s office—covering what would become Lake View Township, as well as a piece of the future Rogers Park—shows the landscape as it was in the early 19th century. (Federal Township Plats for the entire state are available at the Illinois State Archives’ website.)

In the copy of the map below, I’ve added modern-day street names next to the township section lines, showing how the map corresponds with today’s North Side. And I’ve added a green tint to the areas labeled as “timber,” which were outlined by green lines on the original map.

The map, which appears to be based on a survey from 1821,12 might help explain why people initially used the Clark Street route instead of traveling closer to the lakefront. Going north along the route where Broadway is today wouldn’t have been easy: You’d have to traverse five miles of swamp. However, Albert Scharf’s map of Indian trails does show what appears to be a trail following a route quite similar to Broadway.13

North Side swamps

The map shows timber covering most of the land near the lake, as well as a stretch running along the Chicago River’s North Branch. A couple of miles west from the lake, more of the land was prairie.

Chicago was famously swampy when it became a town in 1833, and this survey found plenty of wetlands in Lake View Township. The mapmakers colored these areas as blue.

The south end of the swampy corridor was roughly where the corner of Waveland Avenue and Broadway is today. At the south end, it was swampy prairie.

A bit north of Lawrence Avenue, there’s an area labeled simply as “swamp,” where the forests appear to overlap with the wetlands. Continuing north, these swampy woods change back to swampy prairie around the modern-day location of Devon Avenue.

I recently read Leila Philip’s book Beaverland: How One Weird Rodent Made America, which makes me wonder: Did beavers, which were once plentiful in this part of the world, make dams that shaped these wetlands? As Philip notes, North America’s beavers changed the flow of rivers and streams, creating ponds and wetlands.

“Once beavers were gone … not only did the wetlands dry up, but the very shape of function of riverine systems changed,” she writes.14

At some point in the past, did any streams run through the land in the North Side’s Broadway corridor? And did beavers transform it into swamp? I’m only speculating here, but it strikes me as a plausible theory.

“Wooded swamps are at the end stage of a fen-bog-swamp succession, legacies of the Ice Age, when the melt started the sequence by first creating stupendously huge lakes,” Annie Proulx wrote (in The New Yorker’s excerpt from her 2022 book Fen, Bog and Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and Its Role in the Climate Crisis).

Swamps were “universally detested” by the white settlers spreading out across the continent, Proulx wrote; people drained these swamps or filled them in, transforming them into farms or making the land suitable for human habitation.

The territory now covered by the United States had an estimated 221 million acres of wetlands in the early 17th century. By 1990, that soggy ground had been reduced to 103 million acres.15 The swamps on Chicago’s North Side were eventually swallowed up by the Lake View, Uptown, Edgewater, and Rogers Park neighborhoods.

According to Conrad Bristle, an immigrant from Baden-Württemberg who reportedly moved to Lake View as a boy in the 1850s,16 the area often flooded when strong winds blew in from the lake. “It was not uncommon for the water to be several feet deep in the street even as far west as Broadway and Montrose,” Harold Charles Hoffsommer wrote in 1923, after talking with Bristle.

The German immigrant also recalled that the area east of Broadway had been “nothing but sandy timber land” in the mid-19th century. As a boy, Bristle lived close to the lakefront, which was near the modern-day location of Clarendon Avenue at that time. He trapped prairie chickens, quails, and wild pigeons (possibly passenger pigeons, the species that went extinct in the early 20th century).

“As a boy he shot barrels of wild pigeons on the ground which is now Graceland Cemetery where they were thick as late as 1890,” Hoffsommer wrote.17 (Bristle and his family do not appear in Lake View in the 1860 U.S. census, so it’s possible they actually arrived later than the 1850s.18)

Farther west, Green Bay Road served as a route for stage coaches by 1850. Roadhouses opened to offer drinks, food, and lodging to these travelers. The earliest roadhouses included Baer’s Tavern, near the future site of Rosehill Cemetery.19

Before this area was called Lake View, it was known in 1850 as Ridgeville Township, which also encompassed the areas now known as Evanston and Rogers Park,20 as shown in this map.21

In 1850, the U.S. census counted 441 residents in Ridgeville. Nearly all of them were farmers, but there were three people keeping inns or taverns.22 In 1857, Ridgeville was split up into Evanston and Lake View Township. 23

After receiving a petition from people who owned land along the old Green Bay Road, Lake View Township hired a surveyor to map the route on October 7 and 8, 1857. The town soon declared it to be a public highway.24 A month later, Sulzer Street—known today as Montrose Avenue—was laid out.25

The rural cemetery boom

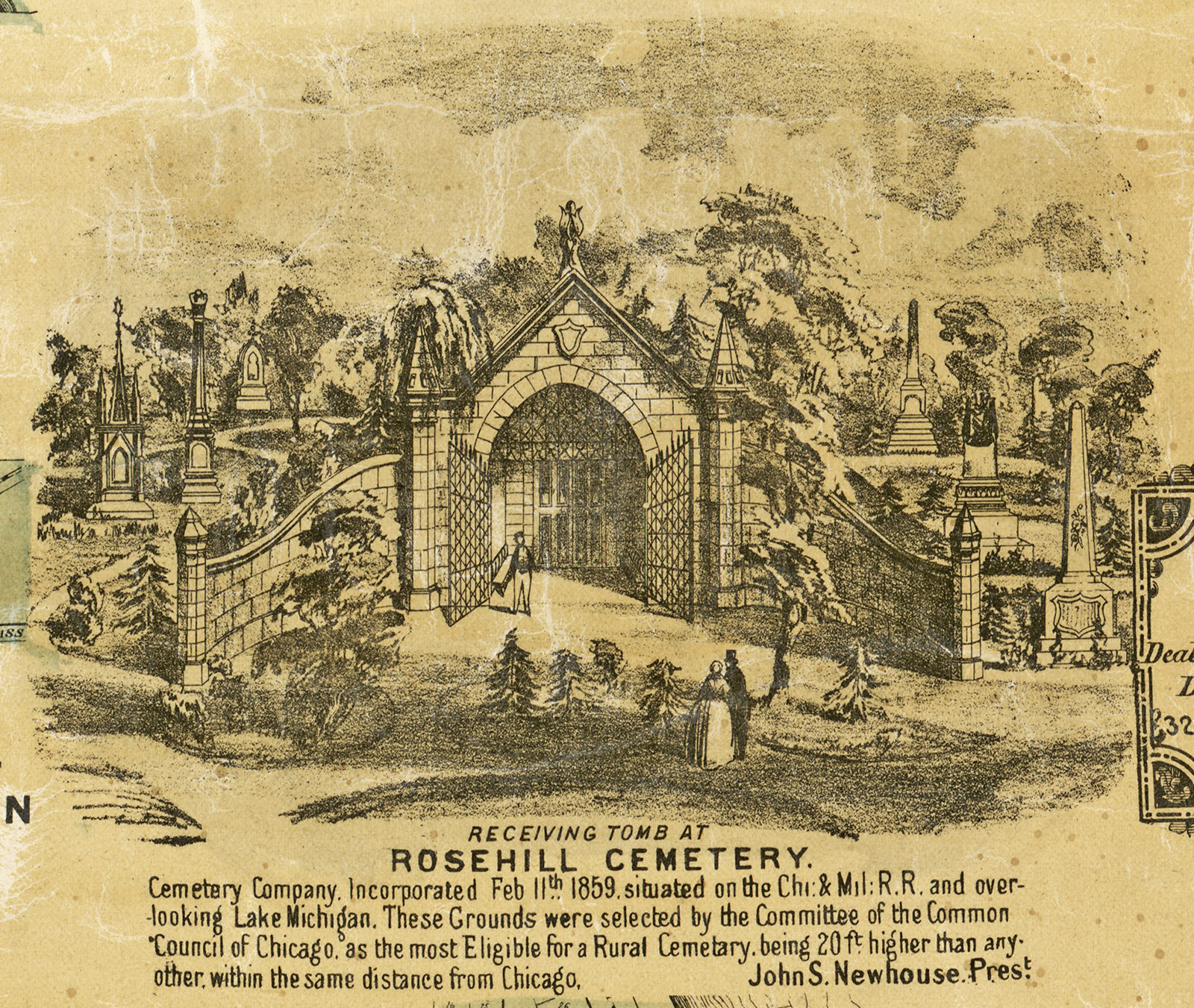

Several cemeteries were established along this rural road between 1851 and 1863, part of a trend called the rural cemetery movement. It became fashionable to bury your loved ones in landscaped parks out in the countryside, instead of graveyards in the midst of a crowded city.28

These new cemeteries were “located out of the busy crowds of cities, in the stillness and quiet of the country, amid the beauties of natural scenery, where ‘man may go to his long home and sleep undisturbed forever,’” Chicago physician John H. Rauch wrote.29

But there was another reason why Rauch was pushing for rural cemeteries. Along with other Chicagoans, he believed that the city’s cemeteries—clustered east of Lincoln Avenue at North Avenue—were a breeding ground for disease. Those cemeteries near North Avenue were right next to the lake, as seen on this 1863 map:30

Rauch warned that “emanations” from buried corpses were infecting the air and water, so he recommended locating cemeteries outside of the city.

“It should be an elevated site,” he explained,” so that “the gases resulting from decomposition may more readily be diffused through the mass of the atmosphere, and, thus diluted, have less effect upon the health of communities.”31

This was an era when most physicians believed that “disease was carried and spread by ‘miasma,’ or noxious vapors, also called ‘death fogs’ or ‘night air,’” author Benjamin Sells wrote. “The belief was that the miasma contained disease-carrying particles arising from filth, excrement, and decaying organic matter. The filth theory of disease basically said that if something smelled bad, it was bad for you.”

In the coming decades, scientists learned that microscopic bacteria and viruses were actually responsible for spreading disease. But in the meantime, Chicago was facing deadly epidemics of cholera.32

Some people suspected those graveyards, filled with coffins so close to Lake Michigan, the source of the city’s drinking water, were responsible for the horrific diseases killing so many Chicagoans. Responding to these concerns, city officials began taking action in 1858 to curtail burials in the City Cemetery.

Alderman Christian Wahl said that “places for the interment of the dead within the limits of cities are now condemned by the best judgment of science … they are universally regarded … as a violation of all sanitary laws.”33 In 1859, the Press and Tribune (forerunner of the Chicago Tribune) said “the peculiar nature of the soil upon which our city is built” made it unsuitable for graveyards.34

In the midst of this controversy, the Rosehill Cemetery Company formed in 1859, establishing a graveyard on five hundred acres six miles north of the city. A committee of Chicago aldermen selected the site “as the most Eligible for a Rural Cemetery,” because it was “20 ft. higher than any other within the same distance from Chicago,” according to Rosehill president John S. Newhouse.35

When Rosehill (sometimes spelled Rose Hill) was dedicated, cemetery official James V.Z. Blaney gave a speech praising “this beautiful spot.” But he also took the opportunity to denounce the practice of burying people in city cemeteries, saying it was evidence of “stolid ignorance and degraded morals.”36

Graceland Cemetery opened a year later. “The natural topography of the grounds is admitted by all to be peculiarly beautiful—the gentle undulations and the grove of old trees over the entire subdivision, having suggested the name of ‘GRACELAND,’” the cemetery declared in an 1860 advertisement.

Surveyors emphasized the property’s elevation: “We have taken levels over the surface of Graceland Cemetery, and find the minimum height to be 17 feet, and the maximum height to be 26 feet above the present stage of water in Lake Michigan; most of the ground being 20 feet above, which is four times the usual depth of graves.”

They were probably offering this data as reassurance: There was no need to worry about bodies in Graceland leaking disease into Chicago’s water, because the cemetery was on higher ground.

Graceland’s owners also reassured Chicagoans that they’d be able to reach this cemetery in a remote, rural location two miles outside the city. They offered rides on a horse-drawn omnibus, taking passengers to and from the city limits. Tickets were eight cents.37

Graceland soon became a popular destination. An 1862 notice in the Tribune suggested visiting “this beautiful city of the dead.”38

Two smaller graveyards had opened earlier just south of Graceland: the Hebrew Benevolent Society Cemetery (Jewish Graceland Cemetery) in 1851,39 and First German Lutheran Cemetery (Wunder’s Cemetery) in 1859.40

Completing the area’s cluster of graveyards, the German Angel Guardian Orphan Society opened St. Boniface Catholic Cemetery at the northeast corner of Clark Street and Lawrence Avenue in 1863.41

Meanwhile, Chicago prohibited any further burials in the cemeteries around North and Lincoln Avenues. Those graveyards were transformed into Lincoln Park, and many of the 35,000 graves were moved to the new cemeteries in the countryside.

But as Pamela Bannos documented in her Hidden Truths project, it was a haphazard process, so it appears likely that thousands of bodies remained in the ground under the new park.42 (Read my 2008 Chicago Reader story about Pamela Bannos’s Hidden Truths project: “A Conservatory, a Zoo, and 12,000 Corpses.”)

In hindsight, there’s little reason to believe that the human corpses buried in Chicago’s old cemeteries had much, if any, effect on the populace’s health. As physicians gained a better understanding of how germs spread illnesses, Chicago officials turned to another way of keeping disease out of the city’s water supply: reversing the Chicago River.

Whether or not it was justified, the panic about miasma from graveyards resulted in the creation of some beautiful cemeteries.

Farm country

As these cemeteries opened, Lake View Township was sparsely populated. In 1860, only 587 people were spread out across its 10½ square miles—at a time when the city of Chicago had 109,260 residents.

The most common birthplace for Lake View residents was Illinois, but the township’s 170 Illinois natives were almost all children—only six were 18 or older.

There were 147 immigrants from various German states, along with 54 people from Ireland, 40 from England, 38 from New York, 36 from Luxembourg, and 16 from Massachusetts.

The residents included 41 gardeners, 17 farmers, and 14 farm laborers, plus 29 other laborers and 29 servants. A handful of men worked in other professions: The census counted four lawyers, two blacksmiths, two brewers, one physician, one overseer, one milkman, and one person described as a “gentleman” (Daniel T. Elston).43

“Wealthy Chicagoans seeking summer retreats from the city’s heat and disease bought up land in the eastern sector of the area,” Amanda Seligman wrote in the Encyclopedia of Chicago. Meanwhile, much of the land was being transformed into farms. “Farmers from Germany, Sweden, and Luxembourg made celery Lake View’s most important local crop,” Seligman wrote.44

“The soil being rather sandy, celery and potatoes were the chief crops,” Hoffsommer wrote in 1923, after talking with Conrad Bristle about his early memories of Lake View. “The territory was quite thickly grown over with red cedars which formed an excellent wind [break] for the crops.” 45

A local toll road

As the cemeteries increased traffic on Green Bay Road, Cook County granted a franchise for the Rosehill and Evanston Road Company to run it as a toll road in 1859.46 As horse-drawn vehicles entered a gate to travel up the road, the company charged them five to ten cents.47

The toll road was controversial from the beginning. On November 8, 1859, the Lake View Town Board passed a resolution asking the toll company to “refund” money that the town had spent on roadwork. The trustees also ordered Lake View’s highway commissioners to stop spending money on the road. They seemed to be saying: Why are we spending money on roadwork here if this road is now run by a private toll company?48

By the time of the 1860 U.S. census, two Lake View residents were working as toll gate keepers: John Eagan and Hiram L. Bartlett.49 By 1868, officials and local residents were complaining about the toll road’s “very bad condition.”50

The problems went on, year after year. According to an 1884 headline in the Inter Ocean, Cook County declared it was a free road and abolished tolls.51 But somehow, that apparently didn’t happen. A year later, tolls were still being collected, and a county official said the road was “in a most horrible condition.”52

In 1886, Bryan Lathrop, a representative of people who owned land along the road, told the Tribune it was “little better than an extended mud puddle.” He added: “Toll-roads are relics of barbarism, and should be done away with.”53

Noting that people had to pay a toll to visit Lake View’s cemeteries, the Inter Ocean declared: “The way the road has been operated is a shame and a disgrace to Cook County.”54

The tolls apparently ended around the time when a streetcar line was extended north on the road in 1886.55 It was getting easier to reach Lake View’s cemeteries, saloons, farms, and homes.

By 1887, Green Bay Road’s name had changed to Clark Street.56 That was already the name of a street through downtown Chicago, which connected with this road at Diversey Avenue—and now the Clark Street name continued north on the former Green Bay Road. It was named after George Rogers Clark, a general in the American Revolution57 who captured the Illinois territory, which had previously been part of the British-controlled Province of Quebec, in 1778.58

The future Broadway

At the same spot where Clark Street crossed Diversey, another road ran north, veering east of Clark Street and then following a northward path that was roughly parallel with Clark.

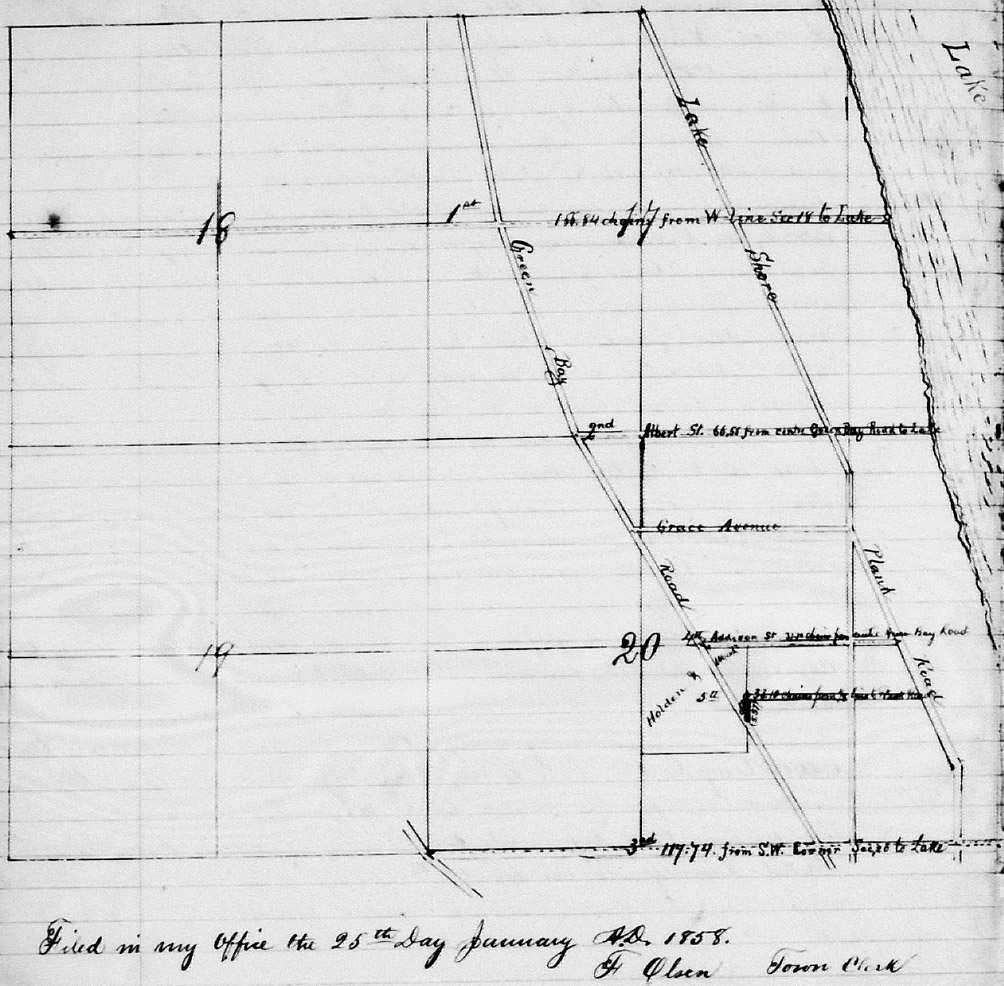

That route became Evanston Avenue, which has been known since 1913 as Broadway. It appears on an 1858 map as the Lake Shore Plank Road,59 but Lake View town officials didn’t take formal action to create the road until 1860.

Responding to property owners along the route, the town’s trustees “did … personally examine” the corridor on February 16, 1860, and had it surveyed a month later.60 An 1860 ad called it Lake View Road.61 The route was shown on a map from December 24, 1863.62

At the north end, this road veered northwest from Bryn Mawr Avenue, a diagonal stretch that’s now called Ridge Avenue.

Lake View Township laid out separate street heading straight north from Bryn Mawr to Devon Avenue. An 1860 survey noted that this street (now part of Broadway) ran through “marshy ground,” another remnant of those old wetlands.63

The future Broadway was also known as Dummy Road, a name it got from the type of trains that operated on it. A “dummy” was a steam locomotive enclosed in a wooden box structure—a way of disguising the locomotive car as a passenger coach. By 1887, the road had become Evanston Avenue, named after the town on its northern end.64

Lake View Township’s population boomed from 2,000 in 1879 to 45,000 by 1887,65 when it was incorporated as a city.

But a Chicago-area newspaper called the Budget seemed unimpressed with this area, asking: “Has the North Side no ambition beyond cemeteries and road-houses?”66 The number of saloons in Lake View had increased along with the population, going from 26 in 1879 to 176 a decade later.67

Lake View was annexed by the City of Chicago in 1889,68 the same year Pop Morse decided to buy some property there along Evanston Avenue. Of course, not everyone in Lake View wanted to become part of Chicago.

During the debates over annexation, the Tribune reported that the suburb’s saloonkeepers were “on the anti-annexation side of the fence.”69

Read the next chapter: The Sunnyside, Cemetery Saloons, and the Rise of Ravenswood

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Footnotes

1 Harold Henderson, “The High Ground,” Chicago Reader, March 29, 2007, https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/the-high-ground/Content?oid=924637.

2 John C. Hudson, “Topography,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1260.html

3 Michael J. Chrzastowski, “The Chicago River—A Legacy of Glacial and Coastal Processes Guidebook for the 2009 Meeting of the North-Central Section of the Geological Society of America Rockford, Illinois April 2–4, 2009,” Illinois State Geological Survey, 12-15, http://library.isgs.illinois.edu/Pubs/pdfs/guidebooks/guidebook-37.pdf.

4 “The Earliest Americans Arrived in the New World 30,000 Years Ago,” University of Oxford, July 22, 2020, https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2020-07-22-earliest-americans-arrived-new-world-30000-years-ago.

5 Interview with John Low, August 14, 2021; “Potawatomi Oral Tradition: The Creation of the World,” Milwaukee Public Museum, accessed April 3, 2023, https://www.mpm.edu/content/wirp/ICW-137. Adapted from Alanson Skinner, “The Mascoutens or Prairie Potawatomi Indians, Part III, Mythology and Folklore,” Milwaukee Public Museum Bulletin 6, number 3: 327-411; William Jones, collected by, Truman Michelson, ed., Ojibwa Texts (Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill, 1917), Publications of the American Ethnological Society, Volume VII, Part I, 403-409, https://archive.org/details/ojibwatextscoll07jonerich/page/402/mode/2up

6 John C. Hudson, “Topography,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1260.html

7 “The Elevation of Chicago: A Statistical Mystery,” Chicago Public Library, September 29, 2014, https://www.chipublib.org/blogs/post/the-elevation-of-chicago-a-statistical-mystery.

8 Ray Noesen, “The Road to Green Bay: Chicago to Andersonville Geological Site,” Edgewater Scrapbook 10, no. 1 (Winter 1999), http://www.edgewaterhistory.org/ehs/articles/v10-1-1.

9 Albert F. Scharf, Indian Trails and Villages of Chicago and of Cook, DuPage and Will Counties, Ills. (1804), 1900-01, Wikipedia, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fa/1900_Map_-_Chicagoland_Indian_Trails_of_1804_by_Scharf.jpg.

10 Ray Noesen, “The Road to Green Bay: Chicago to Andersonville Geological Site,” Edgewater Scrapbook 10, no. 1 (Winter 1999), http://www.edgewaterhistory.org/ehs/articles/v10-1-1.

11 A.T. Andreas, History of Chicago, Volume I (Chicago: A.T. Andreas, 1884), 141, https://books.google.com/books?id=wP0TAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA141.

12 Townships 40 and 41, Cook County, United States Surveyor General’s Records for Illinois, Record Series 953.012, “Federal Township Plats,” Illinois State Archives, http://www.idaillinois.org/digital/collection/IllinoisPlats.

13 Scharf.

14 Leila Philip, Beaverland: How One Weird Rodent Made America (New York: Twelve, 2022), 166.

15 Annie Proulx, “Swamped,” New Yorker, July 4, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/07/04/swamps-can-protect-against-climate-change-if-we-only-let-them.

16 “Conrad Bristle, 87, North Side Pioneer Is Dead,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 26, 1933, 16; Bristle Family Tree, accessed March 4, 2023, Ancestry.com; 1920 U.S. Census, Chicago Ward 23, Enumeration District 1297, Sheet 5A, at Ancestry.com.

17 Harold Charles Hoffsommer, “The Development of Secondary Centers Within Metropolitan Cities: ‘The Wilson Avenue District,’ Chicago” (master’s thesis, Northwestern University, May 19, 1923), 23-24, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/ien.35556034986190?urlappend=%3Bseq=6%3Bownerid=13510798902015057-12,

18 Author’s analysis of U.S. census, 1860, Lake View Township, Cook County, Illinois, at Ancestry.com.

19 “Suburb Once Wicked,” Inter Ocean, May 18, 1900; Clyde D. Foster, “Green Bay Travel Tips, 1850,” in “A Line O’ Type or Two,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Nov. 20, 1945.

20 “Ridgeville,” Rogers Park West Ridge Historical Society, accessed March 23, 2023, https://rpwrhs.org/w/index.php?title=Ridgeville.

21 Map of the Counties of Cook and DuPage, the east part of Kane and Kendall, the north part of Will, state of Illinois (Chicago: James H. Rees, 1851) https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4103c.la000103/?r=0.503,0.234,0.352,0.191,0.

22 Author’s analysis of 1850 U.S. census, Ridgeville, Cook County, Illinois, at Ancestry.com.

23 “Ridgeville,” Rogers Park West Ridge Historical Society, accessed March 23, 2023, https://rpwrhs.org/w/index.php?title=Ridgeville.

24 1857 minutes, Lake View Township Board of Trustees and Highway Commissioners, 6-9, Illinois Regional Archive Depository, Northeastern Illinois University.

25 1858 minutes, Board of Trustees of the Town of Lake View, 26.

26 Survey of Green Bay Road, October 7 and 8, 1857, Board of Trustees of the Town of Lake View, Minutes, 32-33.

27 1858 minutes, Board of Trustees of the Town of Lake View, 26.

28 Pamela Bannos, “Contributing Factors in Moving the Cemetery,” Hidden Truths: The Chicago City Cemetery & Lincoln Park, accessed Jan. 14, 2023, http://hiddentruths.northwestern.edu/factors.html.

29 John Henry Rauch, Intramural Interments in Populous Cities: And Their Influence Upon Health (Chicago: Tribune Company, 1866), 43, https://books.google.com/books?id=itZNAQAAMAAJ.

30 J. Van Vechten, Chicago (1863), Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/4m90f7663.

31 Rauch, 22.

32 Benjamin Sells, The Tunnel Under the Lake: The Engineering Marvel That Saved Chicago (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2017), 11.

33 “The Day at Rosehill,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 29, 1859, p. 1.

34 Press and Tribune, July 27, 1859, at Bannos, “Contributing Factors in Moving the Cemetery: Sanitary Concerns,” Hidden Truths, http://hiddentruths.northwestern.edu/factors/sanitary.html.

35 W. L. Flower and Edward Mendel, Map of Cook County, Illinois (Chicago: S. H. Burhans & J. Van Vechten, 1861), Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4103c.la000104/?r=0.635,0.32,0.055,0.034,0

36 “The Day at Rosehill,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 29, 1859, p. 1.

37 Graceland Cemetery advertisement, (Chicago) Press and Tribune, August 8, 1860, 1.

38 “Graceland Cemetery,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 5, 1862.

39 “Jewish Graceland Cemetery,” Find A Grave, accessed January 15, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/536866/jewish-graceland-cemetery.

40 “Wunder’s Cemetery,” Chicago Ancestors, accessed January 15, 2023, https://www.chicagoancestors.org/place/wunders-cemetery .

41 “Our History,” Catholic Cemeteries, Archdiocese of Chicago, accessed Jan. 14, 2023, https://www.catholiccemeterieschicago.org/About/History.

42 Bannos, Hidden Truths, https://hiddentruths.northwestern.edu/about_project.html.

43 Author’s analysis of U.S. census, 1860, Lake View Township, Cook County, Illinois, at Ancestry.com.

44 Amanda Seligman, “Lake View,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, 457, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/715.html .

45 =Hoffsommer, “The Development of Secondary Centers…,” 24.

46 The Rosehill & Evanston Road Co. V. People ex rel. W.N. Lawless, 115 Ill. 133, in Homer C. Irish, ed., The American Corporation Cases, Vol. X: Private Corporations (Chicago: E.B. Myers & Company, 1887), 276-279. https://books.google.com/books?id=xoy1AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA276.

47 “Board of Supervisors,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 11, 1868, p. 4.

48 Resolutions passed at the Town Election of Lake View on November 8, 1859, 16.

49 Author’s analysis of U.S. census, 1860, Lake View Township, Cook County, Illinois, at Ancestry.com.

50 “Board of Supervisors,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 11, 1868, p. 4.

51 “The County,” Inter Ocean, April 22, 1884.

52 “The Rose Hill Toll-road,” Inter Ocean, March 28, 1885, p. 6.

53 “No Toll-Road in Theirs,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 15, 1886.

54 “The ‘Snell Road,’” Inter Ocean, June 15, 1886.

55 “That Toll-Road Scheme,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 18, 1886.

56 “Changes Not to be Forgotten: Changes of Names & Places,” LakeView Historical Chronicles, August 5, 2022, https://www.lakeviewhistoricalchronicles.org/2022/08/changes-in-vintage-lake-view.html.

57 Ray Noesen, “The Road to Green Bay: Chicago to Andersonville Geological Site,” Edgewater Scrapbook 10, no. 1 (Winter 1999), http://www.edgewaterhistory.org/ehs/articles/v10-1-1.

58 “Records of the Revolution: John Todd and the George Rogers Clark Illinois Expedition,” Uncommon Wealth, Voices from the Library of Virginia, January 6, 2021, https://uncommonwealth.virginiamemory.com/blog/2021/01/06/23422/.

59 1858 minutes, Board of Trustees of the Town of Lake View, Minutes, October 1, 1855, to February 5, 1866, 26, Illinois Regional Archive Depository, Northeastern Illinois University.

60 March 19, 1860 minutes, Lake View Township Board of Trustees and Highway Commissioners Minutes, 1857 to 1867, 20-21, Illinois Regional Archive Depository, Northeastern Illinois University.

61 Graceland Cemetery advertisement, (Chicago) Press and Tribune, August 8, 1860, 1.

62 Map of Lake Shore Plank Road, December 24, 1863, Board of Trustees of the Town of Lake View, Minutes, October 1, 1855, to February 5, 1866, 60-61, Illinois Regional Archive Depository, Northeastern Illinois University.

63 Road survey, March 17, 1860, Board of Trustees of the Town of Lake View, Minutes, October 1, 1855, to February 5, 1866, 42-43, Illinois Regional Archive Depository, Northeastern Illinois University.

64 “Changes Not to be Forgotten: Changes of Names & Places,” LakeView Historical Chronicles, August 5, 2022, https://www.lakeviewhistoricalchronicles.org/2022/08/changes-in-vintage-lake-view.html.

65 Ann Durkin Keating, “Lake View Township,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, 457, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/714.html; Amanda Seligman, “Lake View,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, 457, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/715.html .

66 “Transportation Wanted,” Inter Ocean, March 4, 1888, p.6.

67 Lake View Saloon and Plumber Licenses, 1879–1890, Illinois Regional Archives Depository, Northeastern Illinois University.

68 Seligman, “Lake View.”

69 “Lake View’s Annexation,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 6, 1887.