CHAPTER 21 of THE COOLEST SPOT IN CHICAGO:

A HISTORY OF GREEN MILL GARDENS AND THE BEGINNINGS OF UPTOWN

PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER

On July 1, 1919, it became a crime to sell alcohol in the United States. Some of Chicago’s drinking establishments started the day by selling beers and light wines containing 2.75 percent alcohol, believing it was legal.1

Other places played it safe. At the La Salle Hotel (located at the northwest corner of La Salle and Madison Streets in the Loop)2, a bartender served a lemonade, asking the lone customer, “D’you want a straw, mister?”

Observing the barkeep, a Chicago Daily News reporter wrote: “He had the sheepish air of a boy caught playing with his little sister’s dolls.” The customer was a traveling salesman from New York. He eyed a cherry floating in the lemonade, took a sip, and pushed the glass back.

“No,” he said, “I don’t want a straw—and I don’t want this Sunday school picnic lemonade, either.”3

A snappily dressed guest walked into the Auditorium Hotel’s bar, asking, “How about a dry martini?” The bartender replied: “Nothing doing, mister. Would a cool glass of buttermilk help any?” Apparently, it wouldn’t. The guest exited, grumbling.4

The Daily News described the gloomy scene at Hinky Dink Kenna’s bar, the Workingmen’s Exchange: “Hundreds of tattered ‘floaters’ stood on the sidewalks whispering sadly of the old days when the street was famous for the ‘biggest schooner in town for 5 cents.’ Their grief was so overwhelming that they were barren of tears or maledictions, or lamentations. They just stood around adding their misery to that of their ragged companions.”5

When a reporter for the Chicago Daily Journal visited the same bar, the doors were locked. “We’re closed tighter than a drum,” an employee told him. “Those birds out there think they’ve just got to stick around in the neighborhood. Why, ho, there ain’t a pint of booze or beer or near beer or anything else to drink in this place; it’s dryer than a brick kiln.”6

After the Workingmen’s Exchange opened for business, a bartender snarled: “Naw, we ain’t got no real beer. Just this sissy near-beer.” When a customer walked up to the bar and said, “Gimme a schooner,” the barkeep turned red with anger, shouting, “Get outta here!”7

On that morning, the legal situation remained confusing. Taking effect on July 1, the Illinois Search and Seizure Act imposed a limit of 0.5 percent on the alcohol content in beverages. But this law applied only to “prohibition territory.”

Did that mean it covered only places with local dry laws? Or was the entire state of Illinois now considered “prohibition territory” now, because of a federal the War-Time Prohibition Act, which also took effect on July 1?8

On June 30, the Illinois attorney general, Edward Brundage, had said, “The state Search and Seizure Act, effective July 1, has nothing to do with territory in the state now wet—Chicago, for instance.”9 That gave some hope to Chicago’s drinkers.

But at noon on July 1, Brundage issued a new statement: “The sale of intoxicating liquor in this state is prohibited by the federal law. … The entire state is prohibition territory.”10

The city’s corporation counsel, Samuel Ettelson, advised Chicago police to enforce the law against beverages with more than 0.5 percent alcohol.11

And Ernest Kunde, president of the State Liquor Dealers’ Association, remarked, “There are many selling that beer and wine today, but now this must be stopped. … We are not going to break any federal laws.”12

In the days that followed, a Chicago Daily Tribune reporter visited some saloons on the West Side and Northwest Side where factory workers drank after finishing their shifts. As the men tasted the “near bear” now being served, some commented, “Not bad.”

But not many of them stuck around for a second round. The bars emptied out earlier than usual. “No, they don’t loiter as they once did,” said Robert Dosien, who ran a bar at 1801 North Sheffield Avenue in Lincoln Park.13

Anton Cermak, a leader of the anti-prohibition movement who’d recently been elected as an alderman, criticized police officers for trying to find bars serving real beer.

“The whole police department, which just had its pay raised as an incentive to detect crime, is running around all over Chicago, ‘detecting’ beer in saloons,” he said. “Bunk! … When the police begin to act as tools and stool pigeons for the Anti-Saloon League and spend their time in saloons that haven’t had any real beer for five days, trying to smell 2¾ percent beer, with the amount of crime there is outside for them to work on, I think it’s time to let the people of Chicago know some things.”14

Moon tunes

As alcohol became illegal, Green Mill Gardens continued offering the same sort of entertainment it always had. In July 1919, one of the attractions was Benny Davis, who’d just left his job as the accompanist for singer Blossom Seeley, the “Queen of Syncopation.”15

Davis was a prolific tunesmith who wrote numerous inane, bouncy ditties.16 His most popular song, “Baby Face,” would come out several years after his Green Mill gig, when he wrote it in 1926 with Harry Akst.17 (Here’s a 1926 recording by the Savoy Orpheans of the song, which was later recorded by Brenda Lee and Little Richard.)

Davis’s tendency to write songs about the moon—his hits included “Indiana Moon” and “Carolina Moon”—was lampooned by Ring Lardner and George S. Kaufman in their play June Moon.18

A rival songwriter, Arthur Schwarz, once complained: “There was a famous lyricist, Benny Davis, who wrote a tremendous number of false rhymes. One of them was ‘home’ and ‘alone,’ which don’t rhyme. And ‘together’ and ‘forever.’” Schwarz’s songwriting partner, Howard Dietz, quipped: “Heaven save us from Benny Davis.”19

The Red Summer

Meanwhile, as the United States entered the age of prohibition, racial tension was rising, with violence in several cities during a season that became known as “the Red Summer.” In Chicago, several attacks by white mobs on African Americans were reported on the South Side.

On July 27, violence erupted when a Black 17-year-old named Eugene Williams drowned in Lake Michigan after a white man threw rocks at him. The days following Williams’s death became known as the Chicago Race Riot. Over the next several days, 38 men—23 of them Black and 15 white—were killed, and more than 500 people were injured.

Afterward, some authorities argued the violence would have been even worse if alcohol had been flowing freely in Chicago at the time.

“Another thing we have to be thankful for is that there was no booze to inspire the hoodlums,” said John H. Alcock, the first deputy police superintendent. “If there had been liquor, the situation would have been a hundredfold worse and the terrors that we had would have seemed like child’s play.”20

“Only in one case does the evidence show that the participants in the riot were in the least under the influence of strong drink,” said E.N. Ware, a member of the Cook County coroner’s jury that investigated the Race Riot deaths. “… It makes one shudder to think what might have been the dire consequences if it had been possible at that time for John Barleycorn to have made himself a part of the rioting mob and have added drunkenness to bestiality and colored hatred.”21

That was speculation, of course. Would the violence have been any worse if Chicagoans had easier access to alcohol? We can only guess. (Read my story from the July 2019 issue of Chicago magazine, marking the 100th anniversary of the Chicago Race Riot by telling the events in the words of survivors and witnesses.)

A question of percentages

Courts around the country were grappling with the question of how to define illegal intoxicating beverages. In Chicago, the Stenson Brewing Company was charged with manufacturing beer that was 1.5 percent alcohol.

As the case was being heard at the city’s federal courthouse, a Tribune reporter interviewed a man sitting in the courtroom, who seemed to be amused by the proceedings.

“Me? O, I’m just loafing in Chicago for a week,” the man said. “Charlie Ward’s my name and I’m from Oklahoma. Fact is, I’m an Indian—college man, too. The members of my race were the first to have prohibition forced upon them. It was invented for our personal benefit by the white man. But the white man started something he couldn’t stop. It got him, too. It’s with the greatest pleasure that I see him going around in the hot sun with his tongue out or gulping down unsatisfactory substitutes for beer. I read in the paper this morning about this case and I hope the government wins.”22

The government did win that case on July 25, when federal judge George T. Page ruled that it was a crime to manufacture or sell any beverages with more than 0.5 percent alcohol.23 The Illinois State Register called it “a complete knock-out decision” against brewers.

“Judge Page is nearly seven feet tall and weighs several hundred pounds,” the newspaper fancifully remarked, surely exaggerating the judge’s actual size. “Apparently he put all of his weight into the blow. … Verily these are dismal days for the jag factories!”24

But brewers in Milwaukee were still making beer with 2.75 percent alcohol—or even more—and it was being sold in saloons around Wisconsin.25 A federal judge in Wisconsin had ruled in favor of selling beer with 2.75 percent alcohol.26

Here’s how the Tribune explained the situation: “Wisconsin smiles on the 2¾ per cent brand while Illinois allows only ½ of 1 per cent in its beer.”27

When Zion grabbed that Wisconsin beer

Federal authorities alleged that Green Mill Gardens paid $505 (roughly $8,800 in today’s money) for shipments of beer with forbidden levels of potency from Milwaukee breweries in the weeks after July 1. It was one of 27 businesses or people accused of purchasing this beer for shipments into the Chicago area during July and August.

Others on the list included “Big Jim” O’Leary, of 4183 South Halsted Street, a gambling kingpin and saloonkeeper.28 (His family’s barn was where the Great Chicago Fire had begun in 1871, when he was a boy.)

These beer transactions came to light after 15 or so trucks and one car—all of them filled with beer—were seized in August by authorities from Zion, a town in Illinois just south of the border with Wisconsin.29

It was a mistake to drive beer through Zion, which had been founded as a religious colony where alcohol was forbidden. At this time, Zion was controlled by church leader Wilbur Glenn Voliva, who insisted that the earth was flat.30

George Remus, a lawyer for the trucks’ owners, filed a federal lawsuit against Zion city officials, arguing that it was illegal for them to confiscate those vehicles “together with the goods, wares and merchandise loaded thereon.”31

Remus, a German immigrant who’d grown up in Chicago, enjoyed confrontation in the legal arena. He was known for “leaping and pacing and prowling the length of the jury box,” Karen Abbott (who has since changed her name to Abbott Kahler) wrote in her 2019 book about Remus, The Ghosts of Eden Park.

The truck company’s lawsuit against Zion was one of Remus’s first chances to attack prohibition laws in the courts. Over the next year, he would specialize in representing bootleggers and taking on prohibition laws such as the federal Volstead Act.

“Remus considered the law to be unreasonable and nearly impossible to enforce, and his clients were proving him right, making astonishing profits from what he called ‘petty, hip-pocket bootlegging,’” Kahler wrote.

Remus would move to Cincinnati and get into the alcohol business himself, becoming known as the “King of the Bootleggers” and making headlines when he shot his wife to death in 1927.32

(Kahler also tells this story in the podcast series Remus: The Mad Bootleg King. And a fictionalized version of George Remus was a character in the HBO series Boardwalk Empire, played by Glenn Fleshler.)

In his 1919 lawsuit against Zion, Remus challenged the constitutionality of the Illinois Search and Seizure Act, arguing that his clients had been “deprived of their property without due process of law and contrary to the Constitution of the said various states and the Constitution of the United States of America.”33

In response, Illinois attorney general Edward Brundage and Lake County state’s attorney James G. Welch argued that the truck drivers had “engaged in an unlawful enterprise of transporting upon the public highway in the State of Illinois, within prohibition territory, intoxicating liquor.”34

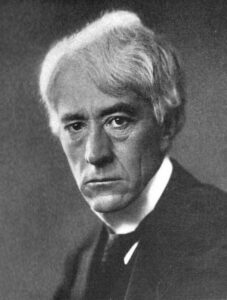

The case ended up in front of judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (who would be appointed in 1920 as baseball’s first commissioner, cleaning up the sport after the Black Sox scandal).

Even though this was an equity lawsuit filed by the truck owners against Zion officials—not a criminal prosecution—Landis used the case as a platform to attack brewers, truckers, and saloonkeepers for breaking prohibition laws.

“Landis … is trying to locate the fountain head of Chicago’s supply of 2¾ per cent beer,” the Tribune commented.35

Landis issued subpoenas for around 200 saloonkeepers who were suspected of serving illegal alcohol.36

He seemed to be especially interested in putting Tom Chamales, the owner of Green Mill Gardens, on the witness stand.37

When court officials failed to find Chamales and bring him to court, Landis took testimony from Green Mill bartenders, who said they hadn’t seen “the boss” for a few days. They also testified that they’d been serving “stiff beer” at Green Mill Gardens.38

Although Chamales was just a witness in this civil litigation, Landis required him to post $15,000 bond “for violation of the United States Statutes in bringing and transporting liquor into dry territory.” Chamales posted $15,000 in the form of Liberty Bonds, but his bond was later reduced to $2,000.39

“You can see the reason this country went dry,” Landis remarked at one point, exasperated by the testimony he’d heard about alcohol being transported into Illinois and sold in Chicago bars. “These men will not respect the law. That’s the reason for this dry spell, sure as you live.”40

James J. Doyle, a chemist for the Illinois Department of Agriculture, analyzed 11 samples of the beer seized in Zion. The alcoholic content ranged from 2.98 to 3.34 percent.41 T.R. Becker, Zion’s police chief, called it “beer with the Wisconsin kick in it.”42

Landis summoned officials from four Milwaukee breweries—Schlitz, Val Blatz, Miller, and Pabst—to explain how their criminally strong beer was making its way into Chicago saloons.43

Arthur F. May, representing the Val Blatz Brewing Company, testified that he was selling 2,000 barrels and 8,000 cases of “real” beer every month. But he insisted that none of his customers were from Illinois.

“How do you suppose they got your beer?” Landis exclaimed. “Some of these bad men got your beer—did they burglarize your plant? You’ve seen trucks with Illinois licenses in front of your place. You thought they were going to sell the beer in Wisconsin, eh? Go into that room and think it over!”44

Landis finally got fed up with Remus, the lawyer for the truck companies, when Remus tried to instruct one of his clients, W.J. Siebold, about how to testify. “Take that man from my courtroom,” Landis thundered. “Escort him clear away. I don’t want him here anymore.”

After Remus was removed from the courtroom, Landis told Siebold: “And now, I don’t want you to monkey with this court any longer. You came in here as one of the petitioners, and by some means got an injunction issued by my colleague, Judge Sanborn, to save your precious trucks.” (Landis was referring to a ruling by Arthur Loomis Sanborn, a U.S. District Court judge in Wisconsin.)

Landis continued: “Now you presume to hide behind constitutional rights for fear of incriminating yourself and associates in the violation of a government law. You tell me now who gave orders for those trucks to go to Kenosha and bring back beer to prohibition territory.”

“Mr. Schaeffer must have given them,” Siebold testified, referring to his business partner. “Yes, I knew what was going on. We got $15 extra per truck for taking a chance in breaking the law.”

“I thought so,” Landis said.45

On October 3, Landis issued an order directing the U.S. marshal “to destroy all beer now in his possession” from the Zion seizures.46 Thirty barrels of beer had been sitting in the corridor outside his courtroom on the sixth floor of the federal building in downtown Chicago.

On October 4, the marshals rolled the barrels away, loading them on trucks while a crowd looked on. The original plan was to dump the beer into the water along Grant Park, but park officials objected. So, the trucks went instead to the Chicago Municipal Pier (which would be renamed as Navy Pier in 1927).

More than a hundred spectators watched as the U.S. government dumped beer into Lake Michigan. According to the Tribune, “a few of the super-thirsty made wild attempts to save a little of the liquor.”47

The Minneapolis Tribune commented on the incident with this headline:

Later that fall, Zion officials held a ceremony to empty out the beer bottles they’d confiscated from other trucks driving through their city. According to one report, 138,997 bottles were emptied into a trough that ran into a sewer.48 Other reports pegged the total at or 84,00049 or 90,000.

“The faithful knelt on the wet ground in prayer after City Attorney Theodore Forby of Waukegan had pronounced sentence of death over the contraband beer. As the first bottles were uncapped the shrill treble of the women smote the lambient atmosphere with song,” a wire service article reported.

“… One unholy person got a good whiff of the perishing brew and tried to break through the lines, but the police leaned on him as the brethren cried: ‘Shame unto you, stinkpot and viper—shame.’”50

This photo in the Library of Congress collection shows beer bottles about to be dumped in Zion—possibly at the ceremony on November 21, 1919.

This photo from the Library of Congress collection appears to be from the same event in November 1919. The archival caption says: “Mrs. Graze Knippen of Zion City holding up bottle of beer as she helps get rid of the beer.”

Remus had better luck with a similar lawsuit he filed in state court, representing the same trucking company, Siebold-Schaeffer. In that case, Harvey Marquis was arrested in McHenry County as he drove a truck filled with beer from Kenosha to Chicago, after he’d been advised to avoid driving through Zion.

After Marquis was convicted, a county judge ordered the sheriff to destroy the truck and the beer, acting under the Illinois Search and Seizure Act. The people who owned the truck and the beer objected, but the law didn’t give them any way of appealing the decision to destroy their property.

So, they sued. The Illinois Supreme Court ruled that this provision of the Search and Seizure Act was unconstitutional. But it did not throw out the rest of the law.51

On October 31, a Chicago Daily Tribune reporter tried to find alcohol in the city, stopping in at various places, including Green Mill Gardens. The reporter concluded that prohibition laws were making it quite difficult to find any booze:

The drys have it. … There may be liquor but it can’t be had by strangers. Last night the loop was quiet and dry. The outlying districts were quieter and drier. Perhaps a friend could get it from a friend, but they had to be good friends.

A stranger toured the loop, the outlying districts and finally (in desperation) the roadhouses in search of bourbon. There was none to be had. The dance, the lemonade, the jazz music was plentiful, but the liquor was not. …

The loop, as seen in the College Inn, the Blue Fountain room, the Winter Garden, Friars Inn, and the North American, was dry as a prune.

To the territory referred to by loophounds as “Little Paris”—i.e., the Wilson avenue district—the stranger hurried. At the Green Mill the waiter shook his head and suggested a horse’s neck. No amount of persuasion or money could change his mind. The band jazzed merrily.52

Prohibition becomes official

On December 15, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the War-Time Prohibition Act was constitutional. The law was still in effect, the justices said, since World War I wasn’t officially over.53

The court’s decision dashed all hopes that Americans might get the chance to enjoy a “wet” holiday before the 18th Amendment imposed prohibition on January 17.54

The ruling “has sort of taken the pep out of the boys,” remarked M.J. McCarthy, secretary of the Illinois Liquor Dealers’ Protective Association. “We really expected to see the saloons open up after the Supreme Court action.”

Most of Chicago’s saloons were still in business, hanging on to their leases and their staffs of bartenders, in the hope that they might win a reprieve. But now, McCarthy predicted that 4,000 of the city’s 5,000 saloons would shut down for good after December 31.

“This will throw about 12,000 men out of employment,” he said. “It is a cheerless Christmas for them and their families.” The 1,000 saloons staying in business would “convert their places into restaurants and soft drink parlors,” he said.55

John F. Butterly had apparently already closed his saloon in the north wing of the Green Mill Gardens building. An advertisement in the Tribune listed the Thor Sales Company at the saloon’s former address, 4812 North Broadway.56 And by the time the U.S. census was conducted for 1920, Butterly had left Chicago altogether, moving to Los Angeles.57

As New Year’s Eve approached, café and cabaret owners insisted that their places were going to be lively during the celebration, despite the lack of alcohol. “The boys who were in France last year are going to raise hell on grape juice and intoxicating music,” one owner remarked.

On December 27, Green Mill Gardens manager Henry Horn said almost every spot at the venue was reserved for New Year’s Eve. “Practically all gone,” he said. “We’re going to pack in 2,200 and let them go to it.”

The situation was the same at Rainbo Garden, a few blocks away. “Absence of J. Barleycorn doesn’t appear to worry ‘em,” said Fred Jackson, a part-owner of the club.58

In the week leading up to January 17, an estimated 50,000 gallons of liquor were moved into private homes, according to the U.S. government.59 Around Chicago, many trucks were seen moving booze on January 16, the final day before the 18th Amendment became law,

In one incident, a truck was hijacked while making a delivery to Rainbo Garden. The driver said the stolen truck had 50 packages, containing what he thought were casks of wine. But when the Tribune asked Rainbo’s manager about this stolen delivery, all he had to say was: “Didn’t expect any booze here.”60

There was not much drinking in Chicago on January 16, according to the Tribune. It was nothing like the boozy farewell Chicagoans had held on June 30, 1919.

In fact, the newspaper said the city’s liveliest event was a meeting of the Chicago Sunday School Association in the Stevens restaurant, where temperance advocates celebrated and drank grape juice. The group performed a chant, using the melody of Stephen Foster’s famous minstrel song “Massa’s in de Cold Ground.”61

A 16-year-old62 Chicago girl named Mary E. Hargreaves had written new words for the occasion. Like the original lyrics, her words imitated the dialect of African Americans. And so, as Chicago reached the end of legal alcohol, a gathering of white people marked the occasion by trying to sing like Black people. And of course, it was a song about John Barleycorn:

Round de loop de hounds am howling,

Hear that mournful song,

While de sober folk am signing,

Happy as de day am long,

Where de hop vine am a dying

O’er de grassy mound,

Old John Barleycorn am sleeping,

Sleeping in de cold, cold ground.

Down in de rum shop,

Hear dat mournful sound,

All de rounders am a weeping,

John is in de cold, cold ground.63

Billy Sunday, the former Chicago baseball player who’d become the country’s most famous saloon-denouncing evangelist preacher, celebrated prohibition’s eve in Atlanta, presiding over a mock funeral for John Barleycorn.

“Good-bye John,” he said. “You were God’s worst enemy. You were Hell’s best friend. I hate you with a perfect hatred. … The reign of tears is over! The slums will soon be only a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and our jails into storehouses and corncribs. Men will walk upright now, women will smile and the children will laugh. Hell will be forever for rent!”64

American—and Chicago—would soon find out just how wrong Billy Sunday was.

PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER

Footnotes

1 Associated Press, “Search-Seizure Law in Effect,” Moline Daily Dispatch, July 2, 1919, 1.

2 “La Salle Hotel,” Wikipedia, accessed November 23, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Salle_Hotel.

3 “Gloom Flows With Pop,” Chicago Daily News, July 1, 1919, home edition (5 o’clock), 1.

4 “Limits Beer Sale in Loop,” Chicago Daily Journal, July 1, 1919, final extra, 3.

5 “Gloom Flows With Pop.”

6 “Limits Beer Sale in Loop.”

7 “Workers Groan Over Near-Beer, But Swallow It,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 4, 1919, 5.

8 Illinois General Assembly, The Revised Statutes of the State of Illinois, 1921 (Chicago: Burdette J. Smith & Company, 1922), 793. https://books.google.com/books?id=xplCAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA793; “Illinois Search and Seizure Law Summed Up,” Chicago Daily News, June 30, 1919, home edition (5 o’clock), 1.

9 “‘Sell Beer,’ Brundage Says; ‘Don’t Do It,’ Warns McBride,” Chicago American, July 1, 1919, afternoon edition, 1.

10 “Prohibition Is in Full Force Says Brundage,” Decatur Herald, July 2, 1919, 1; “Chicago Under Beer Ban: Exemption Does Not Apply Here,” Chicago Daily Journal, July 1, 1919, final extra, 1.

11 “To Enforce Dry Law Rigidly,” Decatur Herald, July 2, 1919, 1.

12 “Illinois Bone Dry Is Brundage Ruling Over Saloon Tangle,” Chicago Daily News, July 1, 1919, home edition (5 o’clock), 1, 3.

13 “Workers Groan Over Near-Beer.”

14 “Cermak Assails Cops Sleuthing for Beer Sales,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 4, 1919, 5.

15 “Benny Davis Opens Act,” New York Clipper, July 2, 1919, 8. https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=NYC19190702.2.68&srpos=44&e=——-en-20–41-byDA-img-txIN-%22green+mill+gardens%22———.

16 Rhoda Koenig, “Musicals / Prowling with the Alley cats: Ring Lardner’s June Moon celebrates a world he despised. Rhoda Koenig on Tin Pan Alley revisited,” (London) Independent, August 25, 1992, https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/musicals-prowling-with-the-alley-cats-ring-lardner-s-june-moon-celebrates-a-world-he-despised-rhoda-koenig-on-tin-pan-alley-revisited-1542538.html.

17 “Benny Davis,” Wikipedia, accessed June 5, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benny_Davis.

18 Koenig, “Prowling with the Alley cats.”

19 Tighe E. Zimmers, That’s Entertainment: A Biography of Broadway Composer Arthur Schwartz (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2021), 186, https://books.google.com/books?id=Fc8vEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA186.

20 “Food Supplies Are Rushed to South Side,” Chicago American, August 2, 1919.

21 Peter M. Hoffman, The Race Riots: Biennial Report and Official Record of the Inquests of the Victims of the Race Riots of July and August, 1919 (Chicago: Cook County, c. 1919), 62.

22 “Indian Smiles at White Man’s Fight for Beer,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 24, 1919, 9.

23 “Court Decides 1-2 Per Ct. Beer Is Intoxicating,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 26, 1919, 17.

24 “A Body Blow for Beer,” editorial, Farmer City (IL) Journal, August 1, 1919, 7, reprinted from Illinois State Register.

25 “Wisconsin News,” Eagle River (WI) Review, August 8, 1919, 2.

26 “Sanborn Quashes 2.75 Beer Case,” (Madison, WI) Capital Times, August 22, 1919, 1.

27 “Voliva Dams Up River of Beer Through Zion,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 16, 1919, 13.

28 “Garrity’s Men Spring Landis Trap on Bars,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 21, 1919, 1.

29 “Voliva Dams Up River of Beer”; Associated Press, “Brewers Testify in Beer Lawsuit,” Moline Daily Dispatch, September 19, 1919, 1; Bill of complaint, George Remus, August 26, 1919, Siebold Schaeffer Co. et al v. Wilber Voliva et al, Equity Case 1287, 1919, Equity Case Files, U.S. District Court, Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division, National Archives, Chicago.

30 “Wilber Glenn Voliva,” Wikipedia, accessed Feb. 10, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilbur_Glenn_Voliva.

31 Bill of complaint, George Remus.

32 Karen Abbott, The Ghosts of Eden Park: The Bootleg King, the Women Who Pursued Him, and the Murder That Shocked Jazz-Age America (New York: Crown, 2019, 5-9; Eli Grey, “Throwback Thursday: Cincinnati’s Most Notorious Bootlegger,” January 7, 2021, https://chpl.org/blogs/post/throwback-thursday-george-remus/; “George Remus,” Wikipedia, accessed September 10, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Remus.

33 Bill of complaint, George Remus.

34 Answer of defendants to bill of complaint, September 15, 1919, Siebold Schaeffer v. Voliva,

35 “Landis Upholds Illinois Beer Seizure Law,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 20, 1919, 7.

36 “Landis Orders Big Breweries to Come to Court,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 18, 1919, 21; “Landis Orders 150 More Liquor Men Into Court,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 24, 1919, 21.

37 “Beer Trucks Are Ordered Back to Zion Authorities,” Libertyville (IL) Independent, September 25, 1919, 9.

38 “Landis Orders 150 More Liquor Men Into Court.”

39 Recognizance of Tom Chamales, September 24, 1919, Siebold Schaeffer v. Voliva.

40 “Garrity’s Men Spring Landis Trap on Bars,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 21, 1919, 1.

41 Associated Press, “Brewers Testify in Beer Lawsuit,” Moline Daily Dispatch, September 19, 1919, 1.

42 “Beer Trucks Are Ordered Back to Zion Authorities.”

43 AP, “Brewers Testify in Beer Lawsuit.”

44 “Garrity’s Men Spring Landis Trap on Bars.”

45 “Brundage Says He Will Punish Beer Dealers,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Sept. 27, 1919, 17.

46 Siebold Schaeffer v. Voliva, Equity Dockets, 6, U.S. District Court, Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division, National Archives, Chicago.

47 “Thirty Barrels of Real Beer Go to Cheer Fishes,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 5, 1919, 6.

48 “Was Big Beer Party,” Topeka State Journal, November 22, 1919, 9.

49 “Beer Smashers,” (Appleton, WI) Post-Crescent, November 21, 1919, 1.

50 “Zion City Spills Beer, Then Prays,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, November 22, 1919, 4.

51 People v. Marquis, 291 Ill. 121 (1919), https://cite.case.law/ill/291/121/,

52 “U.S. Ban Makes City Dry in Fact as Well as Name,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 1, 1919, 17.

53 “War-Time Prohibition Is Held to Be Legal by U.S. Supreme Court,” (Washington) Evening Star, December 15, 1919, 1, 9.

54 Arthur Sears Henning, Chicago Daily Tribune, December 16, 1919, 1.

55 “4,000 Bars to Close Jan. 1,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 16, 1919, 1.

56 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, December 7, 1919, 121.

57 1920 U.S. Census, California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles Assembly District 63, Enumeration District 0149, Sheet 6B, at Ancestry.com.

58 “Active Eyelids Flash Hint of Happy New Year,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 28, 1919, 9.

59 “Liquor’s Knell to Tell in U.S. at Midnight,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 16, 1920, 1.

60 “Liquor Rushed to New Havens as ‘Wake’ Nears,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 16, 1920, 2.

61 “Massa’s in de Cold Ground,” Wikipedia, accessed September 5, 2023, https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Massa%27s_in_de_Cold_Ground.

62 “Mary Jane Hargraves,” Find a Grave, accessed September 5, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/211431951/mary-jane-hargraves.

63 “J. Barleycorn Moves From Loop to Homes,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 17, 1920, 1, 2.

64 A. Cyrus Hayat, “Billy Sunday and the Masculinization of American Protestantism: 1896–1935,” thesis, Indiana University, December 2008, 82, https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/b1d25300-a1c4-431e-84ff-8a942e23bc2e/content.