Chapter 20 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER—>

“This is one of the biggest days in history,” the Chicago American wrote on June 30, 1919. “Nothing like this ever happened before. Nothing like this will ever happen again.”

This was doomsday for Americans who enjoyed drinking alcohol. Or so it seemed to be. It was expected to be the final day when it would be legal to sell alcohol in the United States of America.

Of course, Chicagoans planned to usher out the era by drinking. The American said it would be “a sort of super-New Year’s party,” a prediction that turned out to be accurate.1 It may have been one of the wildest days in Chicago history—and yet, the partying was marked by sorrowful mourning as well as flashes of reckless abandon.

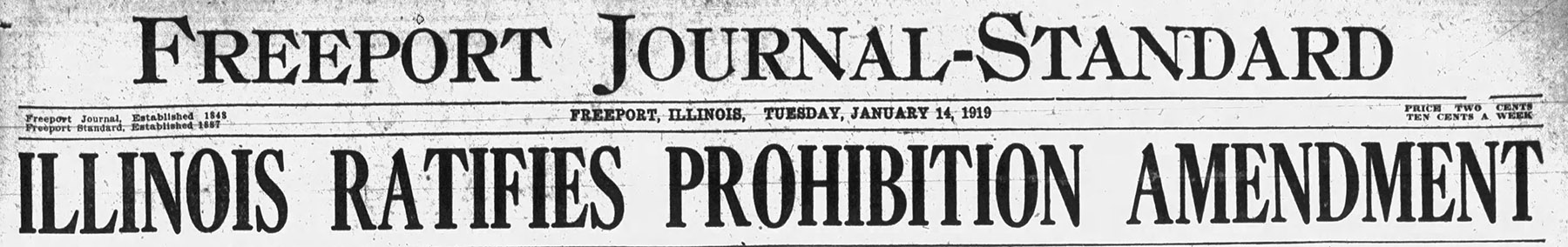

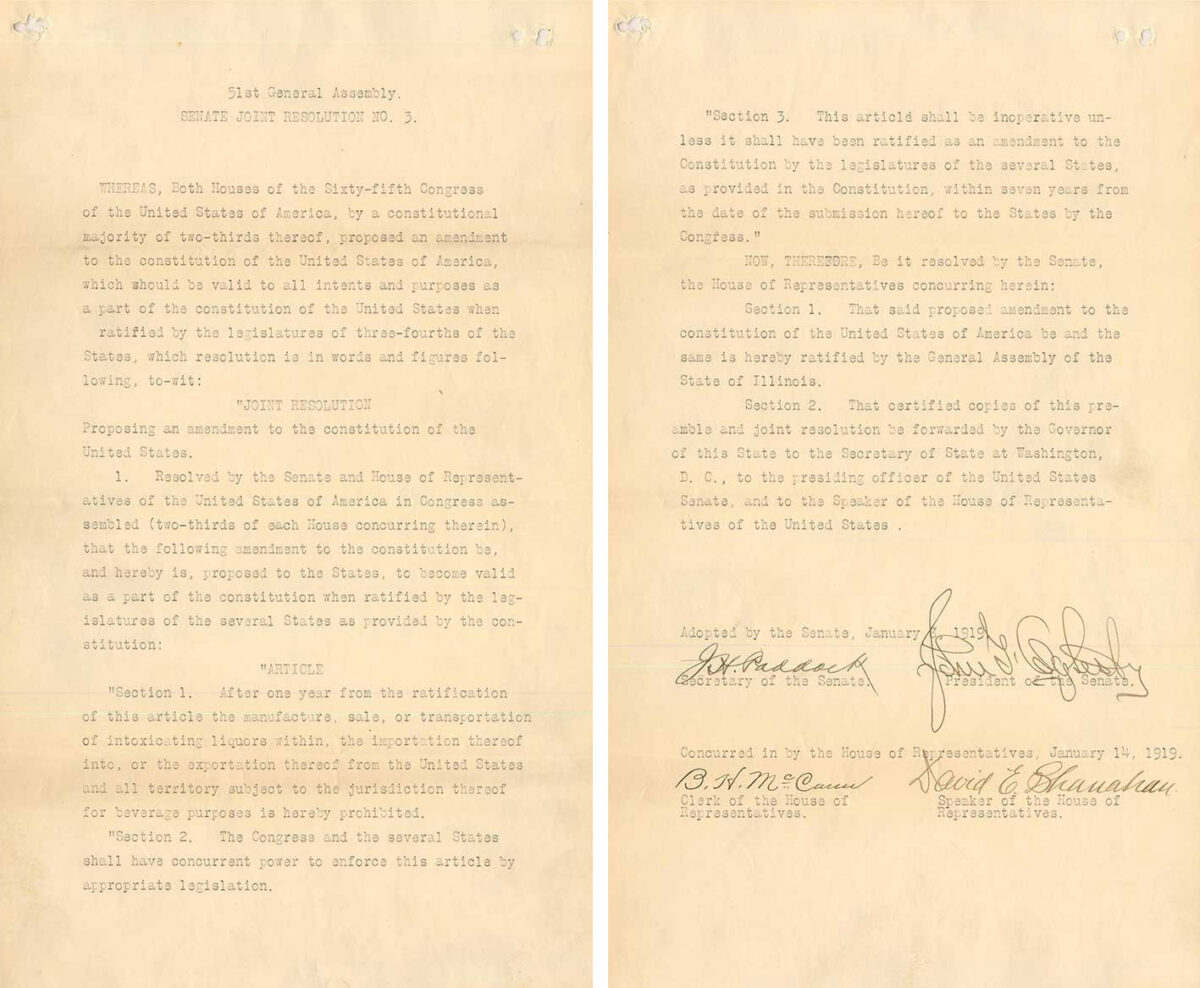

The year 1919 had begun with state legislatures across the country voting for prohibition. Illinois approved the 18th Amendment on January 14.

Two days later, Nebraska became the 36th state to ratify it, making it official: Prohibition would become the law of the land across the United States one year later, on January 17, 1920.2

But the end of legal alcohol sales was actually coming sooner. Congress had approved the War-Time Prohibition Act—even though the fighting in Europe had come to a halt. Thanks to this temporary law, it became a federal crime to manufacture “beer, wine, or other intoxicating malt or vinous liquor for beverage purposes” starting on May 1. And June 30 would be the final date when it was legal to sell intoxicating beverages.

There was much confusion over one big question: What exactly was the legal definition of an intoxicating beverage? The U.S. government’s commissioner of internal revenue decreed that any beverage with more than 0.5 percent alcohol by volume was intoxicating. But brewers pressured the government to allow drinks with a bit more potency,3 arguing that the limit should be 2.75 percent. It remained to be seen how the courts would rule on this question.4

On April 1, Chicagoans voted on a referendum: “Shall Chicago be dry territory?” This election wouldn’t have any practical effect, but 73 percent of Chicago voters said that alcohol should stay legal.5 (In the same election, Bill Thompson was reelected as Chicago’s mayor.6)

In mid-April, the Chicago Daily Tribune observed changes happening in a district of breweries along the South Side’s lakefront between 24th and 28th Streets, which it called “one of the greatest brewing centers in the world.” As booze became illegal, this area seemed to be transforming into a “soft drink center.” The Tribune predicted: “No longer will the smell of hops permeate the air in that district.”

The Conrad Seipp Brewing Company, located at the foot of 27th Street, was already making near beer.7

The National Association Opposed to National Prohibition encouraged people to wear daisies on June 30 as a symbol of protest. Why daisies? Simply because these flowers were in bloom around the country in late June.8 Chicago’s hotels planned to distribute 10,000 daisies on June 30. Restaurants and cafes were also handing out the flowers.9

Some people hoped that this ban on booze would be temporary. After all, the war in Europe seemed to be over. But the War-Time Prohibition Act was in effect “until the termination of demobilization, the date of which shall be determined and proclaimed by the President of the United States.”10 And president Woodrow Wilson—who was in France, signing the Treaty of Versailles on June 28—hadn’t completely demobilized U.S. troops.

“We are hoping that when President Wilson comes home and sees how the workingmen depend upon beer, especially in this hot weather, he will declare demobilization complete and allow at the least the sale of light drinks,” said Ernest Kunde, president of the State Liquor Dealers’ Association.11

But many people feared that June 30 would be the final day when they could legally buy alcohol. Chicago’s newspapers anticipated the day would be a sort of funeral for John Barleycorn, a character from an old folk song who’d become the personification of the grain used to make alcohol.

An early 19th-century etching by Thomas Rowlandson. Boston Public Library.

Newspapers wrote about John Barleycorn so often that they sometimes used “J.B.” in headlines as a shorthand way of saying “alcohol.”12

People on both sides of the alcohol debate predicted a blowout party on June 30. “This will be the wildest night Chicago has ever seen,” said F. Scott McBride, state superintendent of the Anti-Saloon League of Illinois. “As an orgy it will present the most tangible evidence of the iniquity of drink. And Tuesday morning the whole city, drinkers and abstainers alike, will awake to be glad that prohibition has come.” 13

A cartoon in the Chicago Daily News, June 30, 1919.

“New Year’s Eve will be nothing like it,” predicted Carl Eitel, a proprietor at the Hotel Randolph and Marigold Gardens. “Tables for tonight have been reserved in advance at high prices, and the demand is greater than at any other time in memory. It will not merely be a celebration. The people will turn out tonight in protest against the infringement upon their constitutional liberties.”14

Marigold Gardens (formerly Bismarck Garden), at Broadway/Halsted and Grace Street, was anticipating a crowd of 1,500. Downtown’s Hotel La Salle was opening its rooftop garden to accommodate 3,000 people.15

The American offered this commentary about the night ahead:

The American offered this commentary about the night ahead:

John Barleycorn is staggering around the last lap. He’s groggy. At midnight he’ll done for. Chicago, Illinois, the whole country is going dry—dry for the first time since the Puritan fathers first introduced the Bible and its fellow pioneer, the little brown jug. …

It wasn’t the little white father that took whisky away in this instance. You did it yourself—you and the other fellow. This is a free country and it’s gone and voted itself dry. … Boys, this old town is going dry. You thought it wouldn’t; you said it wouldn’t; you swore it wouldn’t; you bet it wouldn’t. …

They say it is going to be a big night—a sort of super-New Year’s party. The big hotels and restaurants have sold out their reservations. Every saloon in town is going to close up with a loud bang as the lid comes down. Every one is agreed that tomorrow is going to be the one big headache of a lifetime. 16

According to various reports, Chicago had 4,500,17 5,047,18 5,500,19 or 6,000 saloons at the time.20

Many people expected that some of these bars would continue selling beer, even if it was illegal. But when the American talked with the managers of 34 Loop bars, not a single one confessed to any such plans.21

The local U.S. attorney, Charles F. Clyne, who was in charge of prosecuting federal crimes, predicted that Chicagoans would obey the new laws against alcohol.

“I assume at this time that Chicago is a law-abiding community and will comply with the dry law to the letter, beginning at midnight tonight,” he said. “If, however, there should be violations, the law will take its course. … The violators of the law will be sent to jail, and tried.” 22

A new Illinois law was also taking effect at midnight, defining intoxicating liquor as any beverage more than 0.5 percent alcohol.

This was the Search and Seizure Act, which lawmakers in Springfield had approved nine days earlier, allowing authorities to seize vessels, furniture, and vehicles used for transporting liquor. The law also allowed authorities to search buildings, but not private homes. The people of Illinois could keep liquor in their homes—to drink it themselves or serve it to their guests.23

A cartoon by the Tribune’s John T. McCutcheon captured the state of uncertainty. He drew speech bubbles above the city’s buildings, filling them with examples of what Chicagoans were saying:

“Maybe the country will go moist again after demobilization.”

“They’ll probably be pretty severe at first—to set an example.”

“How can they search every automobile?”

“Well, they can’t search a man’s home.”

“I bought a little for a wet day—not for myself but for guests, etc., et al.”

“If you have it in your house, it’s all right, but you can’t take it there.”24

On Monday, June 30, the “farewell parties” were already in progress by 10 a.m. in Stillson’s, a popular restaurant at Madison and Dearborn Streets. This early starting time “seems to be the record for the loop,” the Chicago Daily Journal remarked.25

The celebration in the Loop really got going during the luncheon hour, “when barrooms were packed with patrons and every ‘wet’ cafe was filled with folk of both sexes who believe the demise of King Alcohol should be the occasion for feasting and mirth,” the Chicago Daily News reported.26

Even the oldest saloonkeepers couldn’t remember a day when so many people filled the bars at noon.27 Many Chicagoans did not return to work in their downtown offices on this Monday afternoon. Shoppers crowded into liquor stores, stocking up on booze before it became a crime. Countless Chicagoans wore daisies.28

A Chicago American journalist identified simply as “The Girl Reporter” described her experiences in the crowds of drinkers: “The oafish wits … slide up to you and, after merrily slapping the sunburn on your shoulder, guffaw, ‘Are you going to the wake tonight?’ That was your cue to come back with ‘Whose wake?’ ‘John Barleycorn’s,’ triumphed the wit with a chortle.”29

It did not take long before some of the Loop’s saloons closed their doors and posted signs saying “sold out.”30

“By noon, June 30, there wasn’t a saloon in Chicago that had a barrel of real beer left,” recalled Anton Cermak, a leader of the anti-prohibition movement who’d been elected to the City Council in April. “The big final night’s celebration was a near beer affair all the way through. What drunks there were resulted from whisky and other heavy liquors. There wasn’t a beer jag in town, unless some youngster had a make believe.”31

As the day went on and booze became scarcer, some saloons raised their prices.32 By 7 p.m., the Loop’s saloons were so crowded that the men and women packed inside could barely move.33

At 8 p.m., Daily News reporter Eugene E. Morgan was in a “corner saloon” at Broadway and Lawrence Avenue.

The way he phrased that adds to the mystery about the Green Mill’s configuration during this era. Was he talking about a bar inside the Green Mill Gardens complex, at the same spot where the Green Mill Cocktail Lounge and Birrieria Zaragoza are today? Apparently so. Or was there another corner saloon somewhere near Broadway and Lawrence? (Not that we know of.) Later in the same article, Morgan mentioned “the Green Mill garden,” but he didn’t make it clear if that was part of the same complex where he was drinking, or if it was nearby. My best guess is that he started the evening in the Green Mill’s corner saloon and then wandered into the garden area behind it.

Green Mill Gardens had recently reopened its gardens for the summer season, touting “10,000 Square Feet of New Outdoor Dance Floor.”

Arnold Johnson, the same bandleader who’d been a big attraction at Green Mill Gardens in 1918, was back, leading a group billed as Arnold Johnson’s Famous Jazz Ragadours.34

Here is how Morgan described the scene on June 30:

At Broadway and Lawrence avenue the corner saloon is full and running down the sides with thirsty humanity. The bartenders are mixing jests and philosophy, but no fancy drinks. The unwashed glasses are piling up, and across the bar is drifting enough coin of the realm to shoe an orphan asylum.

At a small counter there is a “sale” on hip pocket flasks. Apparently there are more hips than bottles. A gray bearded vendor of shoe strings, who announced himself as “Daddy,” winds through the crowd, but sems able to convince no one that there will soon be a ban on shoe strings.

A bluejacket band is blaring in the Green Mill garden and a record audience is assembling for an open air adieu to the Falstaffian scoundrel of the ages. Broadway is a roaring mess of taxicabs. Folk with bulging packages pile into family cars, then drive away with a laugh and a song.35

The Tribune also reported that Green Mill Gardens had the biggest crowd in the venue’s history up until that time. The same was true for the other North Side hot spots, including the Marigold Room at Broadway and Grace (a.k.a. Marigold Garden); Rainbo Garden, at Clark and Lawrence; and the Sheridan Inn, at Devon and Sheridan.

“Unless one had arrived early there was no table to be had at any of the resorts,” the Tribune reported. “All had the S.R.O. sign out.” All of these North Side venues announced that they would continue to operate as soft drink cafés with dancing after the War-Time Prohibtion Act took effect.36

In the Daily News, Morgan described what he saw at the Marigold around 8:30 p.m.:

The Marigold is a pot of fermented honey, around which taxicabs buzz. In the barroom things have begun to finger up; youths are wailing college sons and the navigation laws of all well conducted gin mills are being violated by reeling customers.

In the garden a windmill is turning and the rainbow hues of fountain spray add color to the scene. In the ballroom a starfish are dancing—starfish worn as hats by a dozen coryphees. All at once every starfish opens its eye; it’s an electric bulb device, but the effect is so oceanic as to call for another quart of champagne for the fat citizen who is entertaining out of town customers. 37

Amid these festivities, news arrived from Washington: U.S. attorney general A. Mitchell Palmer said the Justice Department would hold off on prosecuting people for selling beer and wine containing up to 2.75 percent alcohol—until the courts ruled on the definition of “intoxicating.”38

This statement caused some confusion. When someone told the news to Edward Brundage, the Illinois attorney general, he mistakenly thought the federal government was formally changing the booze benchmark to 2.75 percent.

“I said that if this were true, it would be permissible under the Illinois law to sell such beverages here,” Brundage later recalled.39

Newspapers reported Palmer and Brundage’s statements. “Beer Saved in Final Hour,” proclaimed a headline in the Tribune.40

William G. Legner, the president of Seipp Brewing, sounded hopeful, remarking: “Chicago may yet have beer.”41

But Chicagoans barely paused in their drinking, as the American’s Girl Reporter observed: “’Twas sundown and the news came galloping from Washington that beer and wine was to live. The noose slipped from the stranglehold on J. Barleycorn’s neck. … But it was too late. The crowd wanted to see the hanging, and so they went right ahead, and there wasn’t a crimp in the ceremony.”42

Another writer for the American commented: “The general situation seems to be that everybody knows John Barleycorn will die at midnight, but nobody believes it. The liquor people especially cannot bring themselves to believe it will be death. Rather they feel it will be a case of suspended animation.”43

Eugene Morgan took a taxi downtown to “hear the loop hounds bark,” as he put it—referring to the downtown drinkers who were known in Chicago as “loophounds.” He reported on the scene in the Loop:

The “L” stairways are crowded with eleventh hour shoppers, burdened with packages, which are oblong and tapering at one end. From every open saloon door issues a potpourri of laughter and yells and what passes for song. Men stagger out and others plunge in. The curbstones and waste paper boxes are reserved for early victims. …

The sidewalks surge with throngs that shriek and groan, and occasionally laugh with a mirthless intonation. … A girl whose hat is straying over one ear tickles a traffic “cop” under the chin with a daisy. Wearing of daises is the best of form—a floral tribute to the almost deceased. An inspired songster at the corner of LaSalle and West Madison streets, weight 200 pounds, is proclaiming, “I’m a little prairie flower.”

On a wooden news stand at West Washington and North Wells streets an orator is addressing the multitude. “Where’s your liberty? Where’s your freedom?” he demands. “The foundation of our liberties is being knocked from under us. The—” A reckless bystander kicks the rostrum and the speaker is sent sprawling. When he gets up there is a fracas and the crowd closes in and multiplies.

As the police pushed their way into that crowd, Morgan went over to the Hotel LaSalle’s roof garden, where he observed:

This crowd is rather glum and thoughtful. When the hour strikes they may shudder as did the guests at the pleasant party given by Edgar Allen Poe when the Red Mask came to foretell the end. Now it is 10; the music resumes and we flee to the hotel bar, where bold serving men are quite indifferent.

“Whisky is all,” says the barkeep at Stillson’s. “Whisky is all, for the beer pump has run dry. What’ll it be, gents? A dry martini? Sure. Come to-morrow. I said, whisky is all.”

A racing car with an open muffler and an exposed nervous system tears down Dearborn street, loaded with young citizenry. It nearly strikes a street car, narrowly misses an old couple and hoots away into the dark.

A straw hat with a punctured crown sails out of a Monroe street headache parlor. We peer into the saloon and observe that the customers are engaged in the boyish pastime of snatching hats. The latest victim is baldheaded and shorn of a sense of humor. “Well, somebody’s got to stay sober to-night, and it might as well be me.”

Andy Moynihan, oldest bartender in the loop, works steadily on in the Majestic bar. Scores of old friends drop in “just to see Andy.” Some are weeping.44

The American’s Girl Reporter saw a man sobbing in the arms of policemen at Madison and Clark Streets. “I’m from Ireland, dear old Ireland!” he wailed. In one place after another, people sang “How Dry I Am.”45 (That was what people called the tune, anyway—it was actually a new song by Irving Berlin titled “The Near Future.”46)

Inside the Congress Hotel’s Pompeiian Room, Morgan saw a man commanding the crowd’s attention by proclaiming: “Now, three last cheers for John Barleycorn!”

Morgan described the reaction: “Glasses are lifted in trembling hands; daisies are flung aloft; men and women, youths and girls leap to their chairs in the roaring requiem.”47

Although it was illegal to sell alcohol to men serving in the U.S. Armed Forces, the American reported seeing “scores of sailors and soldiers brazenly carrying bottles of whisky, taking a ‘nip’ every few minutes.”48

The Tribune commented: “An observer touring the loop, the north, the west, and the south side cabaret districts probably would have remarked that Chicago’s I Will spirit had been temporarily transformed into I Swill.”

But the newspaper also noted the sorrowful spirit of the drinkers: “These were not celebrants. They were mourners. They had a duty to perform. … They clinked glasses, they pledged toasts, they swapped reminiscences, and occasionally indulged in song. But underlying the song and the jest, the laughter and the applause, was the keynote thought—that this was the last night.”49

The American described the Loop at 11 p.m.:

At the Randolph Hotel about an hour before “whisky hour” there were not more than four or five inches of dancing space, but they continued to dance with increasing enthusiasm. The music was wild, and the celebrants were wild. Beautiful young ladies leaned over and kissed their table companions. At the bar men were lined three deep and drinks were passing by the overhead route. Minors bought drinks unnoticed.

The College Inn was jammed to the doors. Women and girls seemed to outnumber the men. They frequently outdid them in eccentric expressions of feeling. The Hotel Sherman bar had a line four deep.50

The police received a telephone message from the liquor store of Louis Glunz at 1202 North Wells Street (which is still open today): “They’re going to hold me up; come—quick.”

When officers arrived, they found 100 customers inside the store, clamoring to be waited on. More than 200 people were outside the store, trying to push their way in. But there didn’t seem to be any robbery. An officer asked Glunz, “Now, who was trying to stick you up?”

The shopkeeper explained that he’d merely been afraid that he might be robbed. “Oh, I took in a lot of money yesterday and I was afraid someone would try to rob me,” he said.51

As midnight approached, Chicago’s aldermen were sitting in a City Council meeting, which had been going since 10 a.m. They leapt into action after learning that 2.75 percent alcohol beer and wine might still be legal.

“All licenses in Chicago expire tonight at midnight,” alderman Anton Cermak pointed out.

He proposed allowing drinking establishments to operate for the next 60 days with a $100 short-term license. If the U.S. government did allow beverages with 2.75 percent alcohol, this would give Chicago saloons a way of legally selling those drinks.

The aldermen approved Cermak’s plan. And then they finally adjourned, at 11:57 p.m.52

Three minutes later at Stillson’s, the dean of bartenders, who was known as “Big Ben,” made an announcement: “Twelve o’clock, gents.” And with that, drinkers began exiting the saloon.

“Twelve o’clock of June 30—a date never to be forgotten,” the Tribune wrote. “… Twelve o’clock. The announcement passed from lip to lip in 4,500 saloons, in the cafés, the cabarets, the summer gardens and the hotel restaurants of this city. It marked the conclusion of the greatest wassailing occasion in Chicago’s history.”53

According to the American, many hotel managers said words to this effect at midnight: “The law will be obeyed. Our buffets and bar rooms will be kept open for business as usual—for such drinks as the law allows.” The American reported that the “lid came down with a bang at 12 o’clock sharp” along Randolph Street, the heart of the theatrical district, known as “Chicago’s Rialto.” Here is how the newspaper described that scene:

The hunting ground of famous loophounds was thronged. The old “Quincy’s Number Nine,” the College Inn, the Colonial Cafe, Righeimer’s and all the others didn’t sell a drop after midnight. At 12:15 more than 600 men and woman stood in the middle of the street and sang “Till We Meet Again.” …

Yes, sir, the Rialto died with its boots on, died game. Policemen ushered crowds out at one door and they flocked in at another. Almost every one sported a “pint on the hip.” …

In the district bounded by Michigan av., Clark st., Randolph st. and Jackson boulevard, touring cars were packed with intervals of inches. Thousands of people overran the sidewalks pulling and pushing one another, laughing and yelling like a frenzied mob.54

The Tribune offered this description of the crowds pouring into the streets at midnight:

From the swinging doors of the dignified La Salle hotel bar to the South Clark street barrel houses they began oozing out—the quick and the dead, the halt and the blind, the bum and the banker, the hick and the loophound, the stenog and the chorus girl, and—but what’s the use? You were there.

Were they stewed? Ask the policemen, the lockupkeepers, the taxicab drivers, the motor bus chauffeurs, the street car conductors, the elevated railroad guards, the unilluminated keyholes. Stewed? All they lacked was a cork and revenue stamp to be bottled in bond.55

On South Clark Street, the famous bar owned by alderman Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna, the Workingmen’s Exchange, closed at midnight.

“Outside its doors are huddled the human dregs of Hoboville, embracing each other for support for feeling their way to the curb,” Morgan reported. “A caller presents a tattered ‘souse’ with a bunch of daises. ‘The compliments of the season,’ says the ‘gob.’”56

A Native American visiting Chicago from Oklahoma—identified by newspaper reports as Blue Snake—had been arrested when a crowd poured out of Hinky Dink’s bar to watch him performing a dance with “realistic blood-curdling war whoops” in the street. Or did he actually get arrested doing the dance in front of the “Sitting Lincoln” statue in Lincoln Park? Reports varied. In any case, he was one of around 1,000 people arrested for drunkenness by 2 a.m.

When the American tried to interview Blue Snake at the Clark Street police station, all he reportedly said was, “Cheap water! Huh! Cheap fire water.” Of course, the newspapers may have been trying to make Blue Snake sound like a stereotypical Indian.

At the urging of other prisoners, Blue Snake did a repeat performance of his war dance in the police lockup. When a reporter saw Blue Snake the following morning, he supposedly said: “White man give fire water; white man take away. When white man going to make up his mind? Ugh!”57

In the Daily News, Morgan described the Loop at dawn—including a stop inside Peacock Alley, a marble-lined tunnel under Congress Street that connected the Congress Hotel and the Auditorium Theatre.58

With the first streaks of daylight over the loop, the mopping out of hotels and restaurants is nearly completed. In a remote corner of Peacock alley a scrubwoman stoops, and her face lights up with pleasure. She had found a faded bunch of daises. They are pleasing to her eye, and as for the story of the night before, she is not concerned. And furthermore, daises don’t tell.59

The Tribune estimated that Chicagoans had spent $1.5 million on alcohol on June 30.60 The American pegged it at $2.5 million.61 Adjusted for inflation, that’s $30.5 million to $51 million.

Summing up the beverage situation in Chicago on the following day, the Daily News wrote: “Buttermilk, strawberry soda pop, non-intoxicating ‘cocktails’ which were really phosphates, cereal beverages—these were chief refreshments that trickled over the bars to-day in Chicago saloons.”62

But Green Mill Gardens and other Chicago saloons soon began ordering stronger beer from Wisconsin.

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER—>

Footnotes

1 “Cork Goes Into Bottle to Stay Tonight,” Chicago American, June 30, 1919, afternoon edition, 3.

2 Daniel Okrent, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (New York: Scribner, 2010), 106.

3 Louis Brandeis, majority opinion in Jacob Ruppert v. Caffey, 251 U.S. 264 (1920), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/251/264/.

4 “To Test Validity of War-Time Law Making Nation Dry,” Buffalo Courier, March 16, 1919, 37; “Elihu Root Tells Brewers to Go Ahead,” Deseret (UT) Evening News, March 18, 1919, 1; “Brewers to Defy Law,” Crookston (NB) Herald, March 28, 1919, 2.

5 “Wets Carry City,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 2, 1919, 1.

6 “It’s Thompson by 17,600!” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 2, 1919, 1; “Chicago Mayors, 1837-2007,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1443.html.

7 Mark R. Wilson, “Seipp (Conrad) Brewing Co.,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/2841.html.

8 “‘Daisy Day’ to Show How Many in Nation Oppose Prohibition,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 23, 1919, 1.

9 “Chicago Local Notes,” Daily National Hotel Reporter, June 30, 1919, 4.

10 Brandeis, Ruppert v. Caffey.

11 “Illinois Bone Dry Is Brundage Ruling Over Saloon Tangle,” Chicago Daily News, July 1, 1919, home edition (5 o’clock), 1, 3.

12 “Law to Wink at Last Wet Splash To-Night,” Chicago Daily News, January 16, 1920, 10th edition, 1.

13 “Stop Beer Sale in Chicago; O.K. in Other Big Cities: Search and Seizure Act Dooms the Saloons Here,” Chicago Daily Journal, June 30, 1919, final extra, 1, 3.

14 “Chicago Holding Wake,” Chicago Daily News, June 30, 1919, home edition (5 o’clock), 1, 3.

15 “Chicago Brewers Plan Fight to Save Beer,” Chicago American, June 30, 1919, afternoon edition, 1, 2; “Stop Beer Sale in Chicago.”

16 “Cork Goes Into Bottle to Stay Tonight.”

17 “$1,500,000 Spent in 4,500 Bars on Day’s Wassail,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 1, 1919, 1.

18 “U.S. Dry Tonight; Brewers Plan Fight on War Act; 5,047 Saloons Here Close,” Chicago American, June 30, 1919, afternoon edition, 1.

19 “Chicago Brewers Plan Fight to Save Beer.”

20 Associated Press, “Search-Seizure Law in Effect,” Moline Daily Dispatch, July 2, 1919, 1.

21 “Chicago Brewers Plan Fight to Save Beer.”

22 “Chicago Holding Wake.”

23 Illinois General Assembly, The Revised Statutes of the State of Illinois, 1921 (Chicago: Burdette J. Smith & Company, 1922), 793. https://books.google.com/books?id=xplCAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA793; “Illinois Search and Seizure Law Summed Up,” Chicago Daily News, June 30, 1919, home edition (5 o’clock), 1.

24 John T. McCutcheon, “July First!” cartoon, Chicago Daily Tribune, July 1, 1919, 1.

25 “Stop Beer Sale in Chicago.”

26 “Chicago Holding Wake.”

27 “Stop Beer Sale in Chicago.”

28 “Chicago Holding Wake.”

29 “How Do You Feel Today? Pardon Came Too Late! By the Girl Reporter,” Chicago American, July 1, 1919, afternoon edition, 2.

30 “Stop Beer Sale in Chicago.”

31 “Cermak Assails Cops Sleuthing for Beer Sales,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 4, 1919, 5.

32 “Stop Beer Sale in Chicago.”

33 “Wet Revels End with Two Dead, Many Hurt,” Chicago American, July 2, 1919, special extra, 2.

34 Advertisement, Chicago Daily News, June 25, 1919, 24.

35 Eugene E. Morgan, “Joy, Gloom Mingle in Last Wet Hours,” Chicago Daily News, July 1, 1919, home edition (5 o’clock), 1.

36 “$1,500,000 Spent…”

37 Morgan, “Joy, Gloom Mingle.”

38 Associated Press, “U.S. Dry at Midnight; Report Sale of Beer May Be Permitted,” Chicago Daily News, June 30, 1919, home edition (5 o’clock), 1; “Court Rule to Decide on Wines,” Chicago American, July 1, 1919, afternoon edition, 1, 2; Arthur Sears Henning, “2 3-4 Per Cent May Be Sold, But at a Risk,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 1, 1919, 1.

39 “Illinois Bone Dry Is Brundage Ruling Over Saloon Tangle.”

40 “Beer Saved in Final Hour,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 1, 1919, 1.

41 “Chicago Brewers Plan Fight to Save Beer.”

42 “How Do You Feel Today?”

43 “Chicago Brewers Plan Fight to Save Beer.”

44 Morgan, “Joy, Gloom Mingle.”

45 “How Do You Feel Today?”

46 “The Near Future,” Wikipedia, accessed September 8, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Near_Future.

47 Morgan, “Joy, Gloom Mingle.”

48 “Obsequies for John Barleycorn,” Chicago American, July 1, 1919, afternoon edition, 2.

49 “$1,500,000 Spent…”

50 “Obsequies for John Barleycorn.”

51 “J. Barleycorn’s Wake Leaves Victim Trail,” Chicago Daily Journal, July 1, 1919, final extra, 3.

52 Journal of the Proceedings of the City Council of the City of Chicago, vol. 88, June 30, 1919, 531, 542, 661. https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofcit88chic/page/661/mode/1up; “Beer Saved in Final Hour”; “Ordinance Passes Council Allowing 60-Day Licenses,” Chicago American, July 1, 1919, afternoon edition, 1, 2.

53 “$1,500,000 Spent…”

54 “Obsequies for John Barleycorn.”

55 “$1,500,000 Spent…”

56 Morgan, “Joy, Gloom Mingle.”

57 “Obsequies for John Barleycorn”; Morgan, “Joy, Gloom Mingle”; “Women ‘Lined Up’ at Bars, Among Booze Rites’ Sidelights,” Chicago American, July 2, 1919, special extra, 2.

58 Adam Selzer, “The Congress Tunnel,” Mysterious Chicago, September 1, 2009, https://mysteriouschicago.com/the-congress-tunnel/.

59 Morgan, “Joy, Gloom Mingle.”

60 “$1,500,000 Spent…”

61 “Wet Revels End with Two Dead, Many Hurt.”

62 “Gloom Flows With Pop,” Chicago Daily News, July 1, 1919, home edition (5 o’clock), 1.