Chapter 19 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

In the midst of Chicago’s turmoil over late-night cabarets, Tom Chamales expanded his local entertainment empire beyond Green Mill Gardens.

In March 1916, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported that Chamales planned to build a 10-story hotel building, including a theater, at the southwest corner of Broadway and Lawrence Avenue—just across the street from Green Mill Gardens.1 In a series of transactions between January 1915 and October 1916, Chamales purchased three lots at the corner, putting together the land where his new building would stand.2

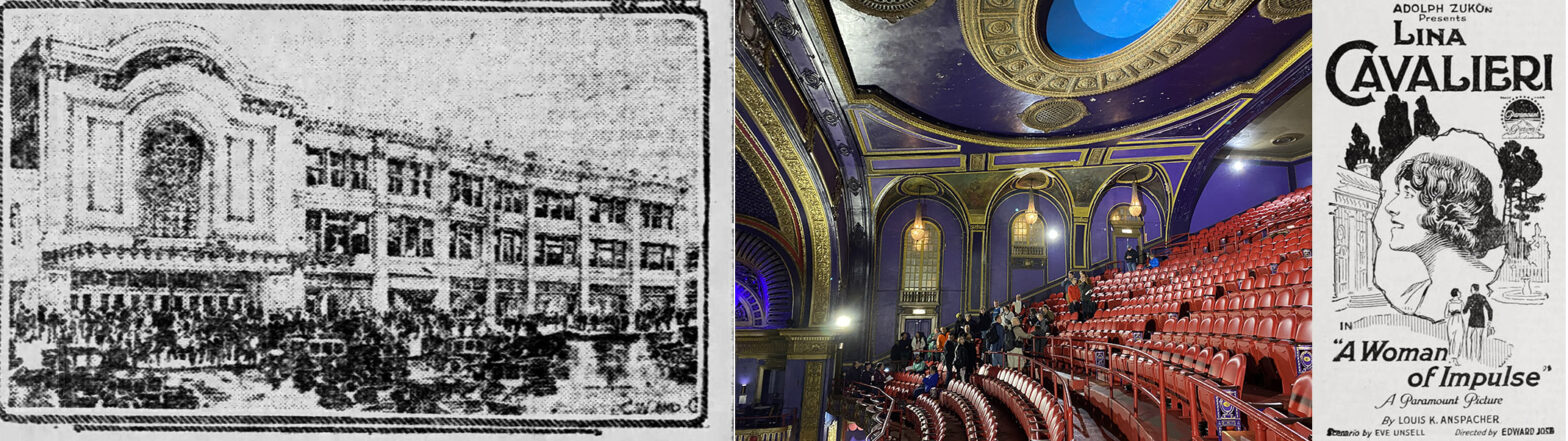

That building became the Riviera Theatre, which is still stands today, well known in recent years as a rock concert venue owned by Jam Productions—”the Riv,” as many concertgoers call it.

Wilco plays at the Riviera on March 23, 2023.

Of course, anyone who’s familiar with this part of Uptown knows that the Riviera’s building isn’t 10 stories tall—Chamales scaled back his plans before starting construction. And it wasn’t originally going to be called the Riviera. When it was being planned, the name was supposed to be either the Broadway Hippodrome or the Broadway Theatre.

To design his ambitious project, Chamales hired Rapp & Rapp,3 a pair of brothers who’d grown up in Carbondale in southern Illinois.

The serious, taciturn Cornelius Ward Rapp had been practicing architecture since the 1880s, designing college buildings, courthouses, churches, and municipal structures across Illinois. One of C.W. Rapp’s employees called him “that crusty old genius,” and another said that “he always looked sore but wasn’t.”

“To his young designers and draftsman, who saw him once a day at 11:00 a.m. when he came down the spiral staircase from his office to the drafting room, he was god,” his great-nephew Charles Ward Rapp wrote in his 2014 book Rapp & Rapp: Architects. “He would pass among the broad drafting tables puffing a pipe as he inspected work in progress. Most often he said nothing. Even with his silence, or maybe because of it, no one doubted his authority.”

In 1907, when C.W. was 47, he’d formed a partnership with his youngest brother, George Leslie Rapp, who was just 29. Their father was a building contract and architect, and their six siblings included another two architects, who had a firm of their own in Colorado.

George had worked as a draftsman and designer for architect Edmund C. Krause on the towering Majestic Theatre at 18 West Monroe Street, a vaudeville house that opened in 1906.4 (Some sources say that C.W. Rapp worked on the building as well.5)

“The interior of the new theater is attractive beyond the usual,” the Architectural Record commented.6 Known for many years as the Shubert, it’s now called the CIBC Theatre.

After starting the Chicago firm of C.W. & Geo. L. Rapp Architects with his brother, George “occupied Rapp & Rapp’s front office where he combined natural charm with his talents as architect, salesman, negotiator, idea man and general liaison between clients and staff alike,” according to Charles Ward Rapp’s book.7

In the years ahead, Rapp & Rapp would design Chicago’s grandest and most famous movie palaces—and many others across the country.8 The Chicago Tribune has called Rapp & Rapp “the Michelangelos of movie palace design.”9

By the time Chamales hired them in 1916, they’d designed several movie houses. The first was a modest 1907 nickelodeon called the San Souci, located inside the South Side’s White City Amusement Park. After that, they’d created the Majestic in Dubuque, Iowa (now called the Five Flags Theater), and the Orpheum in Racine, Wisconsin.

But Rapp & Rapp didn’t fully develop their signature style, inspired by France’s Palace of Versailles and the Second Empire style of architecture, until C.W. got married in 1911—to Mary Payne Root, who was 20 years younger than him—and took a long wedding trip to Europe and North Africa.

The honeymooners booked tickets on the Titanic’s fateful maiden voyage in April 1912 but escaped disaster when they postponed their return, so they could spend more time on architectural sightseeing at places such as the Palais Garnier opera house in Paris.

Charles Garnier’s design for the Paris opera house may have influenced Rapp & Rapp’s movie palaces. From Le nouvel Opéra de Paris.

C.W. Rapp “armed himself with a wealth of on-site information about the shape and feel of classic Beaux-Arts treatment and brought home a trunk of books, most notably two large volumes of Charles Garnier’s color renderings of Paris Opera detail, and collections of Piranesi studies of classical Rome,” Charles Ward Rapp wrote.

Once C.W. got back to Chicago, he and George began designing movie theaters that were more elegant and ornate than their earlier creations: the Windsor at 1235 North Clark Street, which opened in 1913; the La Salle Theater at 152 West Division Street, the Orpheum in Champaign, and the Orpheum in Quincy, all of which opened in 1914; and the Rockford Palace in Rockford and the Al. Ringling Theatre in Baraboo, Wisconsin, both in 1915.10

The Al. Ringling Theatre in Baraboo, Wisconsin, the longtime home to the Circus World Museum, is the former headquarters and winter home of the Ringling Brothers circus Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith. Library of Congress.

As George Rapp once explained, he wanted to create beautiful spaces that would lift people’s spirits, all for the mere price of a movie ticket.

“Watch the bright lights in the eyes of the tired shop girl who hurries noiselessly over carpets and sighs with satisfaction as she walks amid furnishing that once delighted kings and queens,” he said. “See the war-torn father whose dreams have never come true, and look inside his heart as he finds strength and rest within the theater. Here is a shrine to democracy where there are no privileged patrons. The wealthy rub elbows with the poor.”11

As Rapp & Rapp began working for Chamales, they were also drawing up plans for Balaban & Katz’s 1,800-seat Central Park Theater, which would open in October 1917 on Chicago’s West Side, with a lavish Spanish Revival design.

Brothers Barney and Abraham Joseph “A.J.” Balaban had been running the smaller movie theaters known as nickelodeons since 1908—starting with the 100-seat Kedzie Nickelodeon on Kedzie Avenue—but now they were teaming up with family friends Sam and Morris Katz to build venues on a much larger scale.12 Impressed by the style of Rapp & Rapp’s theaters, they began a long collaboration with the brother architects.

“They knew about the Champaign Orpheum, Windsor and the other early Rapp & Rapps, and Sam Katz was pleased with what he saw when he went to Baraboo for a look at the Al. Ringling,” Charles Ward Rapp wrote.13

Regarded by historians as Chicago’s first movie palace—and perhaps the first one built anywhere in the world, depending on how you define what qualifies as a movie palace—the Central Park Theater sparked a trend: showing movies in large, ornate auditoriums with thousands of seats.14 But Balaban & Katz envisioned it as more than just a movie theater. As A.J. Balaban later recalled, he wanted to build 5,000-seat “presentation houses” that were suitable for showing movies as well as hosting live performances.

“My entertainment policy was to combine pictures and ‘flesh’—in what I called (for want of a better name) ‘presentation,’” he said, in a 1942 as-told-to memoir authored by his wife, Carrie Balaban.15 These big theaters would “bring the various arts into one grand finale; blending of the opera to the fastest tempo of jazz; meeting place of the aristocrat and humble worker,” he said in a 1917 interview.16

The Central Park Theater still stands. In 1971, it became home to the House of Prayer Church of God in Christ. Planning began in 2020 to restore and redevelop it.17

It was said to be the first theater in the United States—or possibly in the entire world—with air conditioning, which was a major attraction on hot summer days.

Barney Balaban worked with Frederick Wittenmeier to install carbon dioxide fan-forced air-cooling systems. Wittenmeier, who’d been the chief engineer of the Kroeschell Bros. Ice Machinery Company before starting his own Wittenmeier Machine Company in 1917,18 had developed carbon dioxide refrigeration using patents purchased from Julius Sedlacek.19

As the Chicagology website notes, Balaban & Katz often touted their theaters’ cool temperatures in the years ahead: “B&K constantly hung icicles from newspaper advertisements; Chicago’s Health Commissioner proclaimed their air purer than that of Pike’s Peak; women in the final trimester of pregnancy were admitted free.”20

Construction hadn’t yet begun on the Central Park Theater—ground would be broken in September 191621—when the Tribune announced in August that Rapp & Rapp had completed their design for Chamales’s own theater,22 which would be used for vaudeville, “legitimate drama,” and motion pictures.23 Rapp & Rapp designed a structure with ornate details in the French Baroque style, inspired by the Palace of Versailles.24

By the time Chamales received a building permit on April 25, 1917, he’d scaled down his plans. The building, covering a footprint of 150 by 150 feet, would be three stories tall instead of 10. The estimated construction cost was $325,000,25 but the project’s total price tag, including the purchase of land, was closer to $500,000. Instead of a hotel, the building would include 36 “bachelor apartments” above eight storefronts, alongside the theater.

In a sense, it’s actually two buildings: An L-shaped theater structure wraps around the retail-office-apartment building standing at the southwest corner of Lawrence Avenue and Broadway/Racine Avenue. But there was just one building permit for the two adjacent structures.

Chamales planned to let someone else handle the business of actually running the theater. As construction began, he leased the building for 10 years to Aaron J. Jones, Adolphe Linick, and Peter J. Schaefer, who agreed to pay an annual rent of $25,000.26 (Roughly $600,000 in today’s dollars.)

Chicago Daily Tribune, December 30, 1916.

Jones, Linick & Schaefer had quickly emerged as a dominant theater company in Chicago over the previous few years. By this time, it owned many of downtown’s major theaters: McVicker’s, the Colonial, the Rialto, the La Salle, the Orpheum, the Lyric, the Bijou Dream, and the Studebaker.

“In the innermost office of all the Orpheum you will find Messrs. Jones, Linick & Schaefer at triplet desks, one in the window, and another at each side of the room,” the Tribune reported in December 1916. “Mr. Jones, the president of the firm, is short, dark, slender and very alert. He is a bundle of nervous energy. Mr. Schaefer is rather his opposite, being of serene, jovial, and easy-going presence, while Mr. Linick differs from both the others in being tall, wiry and rather soldierly.

“All seem to be in thorough harmony, which is perhaps the secret of their success. All modestly disclaim being theatrical magnates or any other sort of bugaboo, being anxious to convey the impression that they had been lucky and their only credit lies in being strictly business.”

And now, the company was getting ready to open its first theater outside of the Loop. “The Broadway Theatre will be the newest addition to the Jones, Linick & Schaefer chain and is the only playhouse announced in the outlying district of Chicago attached to this string,” the Tribune reported. “The Broadway will be complete by September 1st, 1917. High Class Vaudeville will be installed, with a policy similar to the ‘Rialto’ and ‘McVicker’s’ Theatres.”27

Excavation began in April 1917. Over the coming months, city building inspectors occasionally visited, taking notes about the building’s progress, as the walls went up. By the end of the year, the building’s roof was under construction.

But in early 1918, the construction work stalled.28 According to a history posted on the Riviera’s website, “the project budget was nearly busted by the rising costs of building materials during the First World War. This caused several construction delays.”29

And for some reason, Jones, Linick & Schaefer’s plans to operate the theater fell through. When construction stalled, Lawrence Stern made a telephone call to bring the project back to life. Stern was a banker at S.W. Straus & Co., which held a mortgage on the building, after making a bond issue loan of $275,000 at six percent interest.30 Stern called up Balaban & Katz, who’d recently opened the Central Park Theater with financing through a mortgage from the same bankers.

“They were looking for a tenant for an unfinished theatre building at Lawrence and Broadway,” A.J. Balaban recalled.

His brother wasn’t enthusiastic at first. “Barney told them that we couldn’t handle it because we had no available cash, and besides, we wouldn’t want it unless it could be finished to our liking,” A.J. remembered.

A.J. Balaban was skeptical about the building’s location. He thought the corner of Wilson and Broadway was the neighborhood’s major crossroads. Although Broadway and Lawrence was just two blocks away, it seemed to him like a less promising spot. And he was concerned about the construction of a competing theater nearby, the Pantheon Theatre, which was going up at 4642 North Sheridan Road, on the west side of Sheridan half a block north of Wilson.31

The Balabans visited the empty shell of the partially completed theater at Broadway and Lawrence, looking it over with the architects, Rapp & Rapp. “Much of the original plan as a vaudeville house was impractical for us and would have to be recast,” A.J. Balaban said. “Nevertheless, I saw in it a dream come true. It was big enough to house long desired features: stage, orchestra pit, fitted playrooms, first aid room in the ladies’ lounge, fine dressing rooms for actors, club rooms for orchestra men and ushers, besides a beautiful lobby for comfortable waiting. C.W. Rapp proved by his plans how it could be transformed for our use.”

Lawrence Stern of S.W. Straus and other financiers provided capital for Balaban & Katz, who changed the theater’s name. “The name ‘Riviera’ was chosen for our newest ‘fairyland,’” A.J. Balaban said.32

Chamales leased the building on April 20 to someone named Lawrence A. Smith, who assigned the lease on July 5 to the Riviera Theatre Company, a business run by Balaban & Katz.33 The 15-year lease took effect on August 1, with a rent of $25,000 a year.34 The city’s building inspectors filed no reports about the construction site between March 26 and August 20, when an inspector notified the owners and architect about a lack of plans at the site. Had the work been idle during those five months? Or had it continued while the inspectors were absent?35

“For months I watched the race between the competing Pantheon being built around the corner and the Riviera,” Balaban said. “Never shall I forget the time I watched until 4 in the morning, not my own theatre but the other one. ‘They poured the balcony,’ I wailed to my patient wife who had expected me home at 1 o’clock (I had married the ‘one and only’ that spring). She answered, ‘Why don’t you watch your own house and not the other fellow’s?’ which I decided was not such bad advice. … Strikes and regular irregularities had held us up in more ways than one.”36

In late July, advertisements for Balaban & Katz’s Central Park Theater began to mention the Riviera, promising that it would open “soon.”37

But the Lubliner & Trinz company’s Pantheon won the race to open first, welcoming moviegoers on September 11, 1918, to watch The White Lie starring Bessie Barriscale. The Pantheon Symphony Orchestra performed during the film, conducted by Alexander Zukovsky, a Kyiv native who’d studied violin in Moscow and joined the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1910.38

The Pantheon, shown in a heating boiler ad. Atlanta Journal, July 24, 1920.

The Pantheon’s ads called it “The Most Magnificent Motion Picture Theatre in the World.”39 The Italian Renaissance–style building (which would be demolished in 1962) was constructed for a reported cost of $750,000,40 although the owners called it “a million dollar theater.” Chicago Daily News movie columnist W.K. Hollander described the Pantheon as “a mammoth house, palatial and costly” and “handsomely decorated.” Thousands of people turned out for the opening night of the Pantheon, which had 3,000 seats, including 2,500 on the main floor.

Hollander noted that movie theaters were continuing to open in Chicago, in spite of concerns that the U.S. government’s war tax might hurt attendance.41 The tax had been imposed on theater admissions in the fall of 1917,42 and some theaters pointed out the 10 percent tax in their ads. For example, evening admission for adults was 20 cents at the Pantheon, plus the two-cent war tax.43 (Adjusted for inflation, that 22-cent ticket cost roughly $4.40 in today’s dollars.)

With seating capacities above 2,000, the Pantheon and Balaban & Katz’s movie palaces were in the same league as two theaters that had opened recently in New York City, the Strand and the Rivoli, where orchestral accompaniment of movies had proved to be popular.44

Movie theaters of that size are almost unimaginable today. Even the biggest blockbuster movies would have trouble filling thousands of seats at screening after screening. How was this possible in the 1910s and 1920s? The simple fact is that Americans bought far more movie tickets in that era than they do today. Box office statistics show that Americans bought an average of 18.6 movie tickets in 1920. In comparison, the average American bought only 2.14 tickets in 2022.45

Chicago Daily Tribune ads from before and after the opening of the Riviera Theatre.

As crowds filled the Pantheon, construction continued on the Riviera. An ad in the September 21 Tribune was vague about precisely when it would open. “Pretty soon, perhaps in a few days, if the artists get through and the artisans too, Chicago will boast a wonder theater, a magnificent place and a commodious one,” it said. “Everybody must visit.”

The ad’s copy emphasized the building’s connection to the Italian Riviera rather than the French Riviera. “It’s called the Riviera and stands in amusements for everything exquisite and comfortable and tasteful architecturally and in entertainment, just as the Italian resort which inspired the name is picturesque and irresistible.”

The ad concluded: “Balaban & Katz, enterprising showmen, directors of entertainment at the Central Park Theater, sponsor the Riviera. Watch for the opening and see for yourself, and bring your friends and your relatives, and not those you dislike. They don’t deserve it. You’ll be compensated. And come again. And again. And again.”46

In late September, Moving Picture World columnist James S. McQuade tried to get a peek inside the Riviera. He didn’t get past the building’s entrance area. “I saw enough … to know that the decorations are going to be extraordinarily fine and the lighting quite unique,” he wrote.

After talking with the night watchman, McQuade reported that “Mr. Balaban and Mr. Katz … are presiding possessively over the last fond attentions in the way of lighting and decoration which the building is now undergoing.” And he noted: “Judging by the bustle of the night crew which was working on the building when I visited it, the work will be completed very soon.”47

A.J. Balaban later recalled that the construction on the Riviera was “unfinished” when it was rushed open.48 On October 2, advertisements announced that the 2,600-seat Riviera, “Chicago’s Newest and America’s Finest Theatre,” was opening at 6 p.m. that night. “In All the World No Place Like This,” the ads proclaimed.

Curiously, the ads did not reveal the title of the motion picture that would be shown. The spectacle of seeing the theater itself was apparently enough to lure a huge audience anyway.49

“How did the people know that the Riviera was going to be good?” A.J. Balaban said. “It seems they smell the sweat and the lifeblood that is poured into an idea that serves the public. All day long, boxes, baskets and packages of flowers arrived, telegrams from every part of the country came from friends, old and new, obscure and prominent, congratulating us on a sure success.

“By 4 o’clock that … afternoon the crowds filled the sidewalks extending around the whole block, and when the doors opened at 6, they poured in like a mountain stream tumbling to the valley below. So happily, so possessively they praised everything. They said to each other, ‘Isn’t it lovely, isn’t it grand,’ taking pleasure in sharing it as if it was their very own.

“I recognized many young patrons from the Kedzie, Circle, and Central Park, now with a baby or two. Remarks could be heard on every side, ‘Oh, yes, I know the Balabans well. I’ve always gone to their theatres since their very first one.’ Everyone seemed to delight in saying how well and how long they had known us.”50

The rear portion of the main floor at the Riveria.

A Riviera ad said: “They came from everywhere—from Evanston, Wilmette, Winnetka, Oak Park, Englewood, South Side, West Side and from the immediate vicinity. Many had to wait for hours to get into the theater. Such a crowd never was seen in one place save at the War Exposition and the World’s Fair.”51

“The theatre is magnificent,” Variety reported. “The decorations are gray and blue, with amber lights giving the necessary warmth of tone.”52

The Riviera’s current owners, Jam Productions, offer this description of the interior:

Architecturally, it is gracious rather than gorgeous, expensive beyond imagination and beyond garishness, French throughout. Silk panels cover the walls, ribbed with snow woodwork; frescoes, restrained in color, dot the ceilings; curved lines guide the eye to the stage. Everything is in the manner of Louis XIV, rich, quiet, aristocratic. An artful balcony arrangement frees the 1,500 first-floor spectators from the huddled feeling of being topped by a gallery. Sweeping domes tower above all the downstairs seats, and yet the second-floor gallery contains 1,000 chairs.

Eight thousand electric lamps are strewn throughout the interior of the house, and yet not one is visible to the eye. Color effects spring from the roof and walls in shaded subtle effects. French windows from passageways give a view of the entire house. From every seat the view of the ninety-foot stage is the same. From every seat the thirty-foot swimming pool, which curves into the stage at its foot and in which mermaids will sport as a prologue when sea scenes are to be shown in films, is visible. No chair so high or so low as to be out of range. In the rear of its huge stage stood the screen 18 x 24 feet in size.53

As I learned during a recent Open House Chicago tour of the Riv, the interior’s color scheme has been predominantly purple for many decades. Original murals are still intact—under a patina of nicotine residue—around the chandeliers on either side of the balcony, with panels representing the four seasons and 12 months of the year.

When the Riviera opened in 1918, Variety noted the building’s other amenities: “There is a beautiful playroom equipped with sand, toys, slides, etc., for children. Leading from this room is a well ordered emergency hospital with a trained nurse in attendance. The attendants use swagger sticks with much efficiency in directing patrons to their seats.”54

Lieutenant W.D. Howett, a former drill instructor for the U.S. Army at Camp Grant in Rockford had trained the Riviera’s corps of khaki-clad ushers “to be punctiliously military,” saluting moviegoers “at a precise angle before they inform you that the only seats left are in the gallery.” According to Moving Picture World, many of these “rookies” were girls and women.55

As it turned out, the opening-night movie was A Woman of Impulse,56 starring Lina Cavalieri.

The rival Jones, Linick & Schaefer theater company would begin showing A Woman of Impulse two days later at downtown’s Orpheum, advertising it as an “Exclusive Paramount Feature” being shown in Chicago for the first time.57 But thousands of Chicagoans had already seen it—at the Riviera.

Lina Cavalieri.

The movie stars Cavalieri as a poor lace-maker’s daughter with a beautiful voice, who gets a musical education with help from a wealthy couple, rising to fame and fortune as an operatic prima donna.58 As the silent film showed on the screen, S. Leopold Kohls conducted the Riviera Symphony Orchestra59—billed in advertisements as a “synchronizing symphony”60 and praised by Variety as “one of the finest in the country.”61

Kohls “had grown up with ‘show business’ in Vienna as [a] pit musician in theatre orchestras where he had become saturated with the lightness and romance of the delightful operettas of the great Franz Lehar and Oscar Strauss,” A.J. Balaban said. “He understood and co-operated fully with my ideas of creating fairyland illusion by the use of music, beautiful girls, color and line.” Before bringing Kohls to the Riviera, Balaban & Katz had featured him at the Central Park Theater. “His continental manners seemed to personalize our entertainment,” Balaban said. “Each woman felt as if deliberately smiled at her.”62

On the Riviera’s opening night, the way the orchestra played along with the film—while the theater added “dainty little touches subtly carried out with lighting effects”—impressed W.K. Hollander as a “performance of unusual merit.”

Writing in the Daily News, Hollander declared: “Of prime importance to Chicago is the launching of the Riviera … a theater erected for the purpose of presenting the silent drama on a higher scale than anything heretofore seen in this community.”

Hollander described a “novelty” that happened in the middle of the movie. The screen star, Lina Cavalieri, really was an opera singer, but obviously, her voice could not be heard in a silent movie. When Cavalieri’s character sang the famous “Habanera” aria in Georges Bizet’s opera Carmen—or rather, when the silent movie depicted her singing it—the theater stopped the movie.

A costumed woman emerged from the darkness, stepping out onto the stage, and sang the aria, which is formally titled “L’amour est un oiseau rebelle” (French for “Love is a rebellious bird”). And then the film resumed. “The thing was accomplished seemingly without a break and fitted in well with the subsequent events,” Hollander wrote.

The identity of the singer who performed “Habanera” on the Riviera’s opening night is unknown. One of the aria’s most famous interpreters was Maria Callas, shown here singing it in 1962:

The Daily News critic was also impressed with the Riviera’s lighting effects for the musicians who performed during the film. “There was a magnificent background for the harpist and when the vocal soloists occupied the stage it resembled a fascinating ball of fire,” Hollander wrote. 63

Afterward, a Riviera advertisement claimed: “EVERYBODY WAS HAPPY. Something distinctive and novel in the way of superior entertainment had arrived in Chicago and it prevailed in a temple of beauty. Art dominated everywhere, in the theatre’s adornments, the music, motion pictures and in the theatrical effects.”64

Another ad summed up the Riviera’s mission: “Where the Motion Picture forms the basic reason but does not constitute the sole entertainment.” In addition to feature films, the theater presented the “Riviera Topical Review,” which it described as a “a resume of the world’s important happenings at a glance; a comedy and other playlets.”

On evenings and Sunday afternoons, tickets were 30 cents for adults and 15 cents for children. The Riviera also offered its full show—with the orchestra and everything else—starting at 2 p.m. on weekdays, with a discount price for these matinees: 20 cents for adults and 10 cents for kids. The advertised prices didn’t include the 10 percent war tax. (Adjusted for inflation, the top price was the equivalent of $6.60 in today’s money.)65

In the Daily News, Hollander offered just one criticism of the Riviera: “The only regrettable thing is that it is not centrally located in the loop.”66 But this was part of Balaban & Katz’s strategy—to open large theaters in the business centers springing up in outlying parts of Chicago. “I wanted one on each side of town,” A.J. Balaban recalled.67

INTERMISSION:

The influenza epidemic

The Riviera had been open for just two weeks when city officials shut down all theaters, trying to stop the spread of influenza during the epidemic that was sweeping the world.

The city’s health commissioner, Dr. John Dill Robertson, had laughed on September 24 when he told the Daily News that there was “no cause whatever for alarm” about the epidemic.68 But as the number of reported cases increased, Robertson began telling people who were suffering from the flu to stay home.69 He warned theater managers to make sure patrons used handkerchiefs when they sneezed and coughed.70

On October 11—as doctors were reporting as many as 1,200 new cases of flu in Chicago each day—the Illinois Influenza Advisory Commission banned dancing in all clubs, cabarets, and halls and prohibited public funerals.71 Within days, the commission ordered movie houses, theaters, and “all other places of public amusement” to shut down October 15 for an indefinite period of time.72

In the midst of this crisis, the Tribune’s movie writer, Mae Tinée—a punny pseudonym used by various journalists at the paper—took a whimsical attitude, observing that “Mister Doctor John Dill Robertson had come to the conclusion that motion picture theaters were the favorite haunt of the busy little influenza germ and must therefore be closed ‘indefinitely.’ (Get that? ‘Indefinitely!’)”73

Tinée interviewed someone from Balaban & Katz, jokingly identifying him as “Mr. Balaban & Katz.” Whoever that happened to be, he “icily” remarked: “All I wish to say, is that fellow with a pickle for his middle name ought to of us put wise before we went and built the Riviera.”74

During the shutdown, some 650 theater workers and 500 movie house employees were out of work.75 “Despite the grumblings of some residents, the closure order had the desired effect,” according to an article at the Influenza Encyclopedia. “Chicago’s loop district, home to most of the city’s entertainment district, was suddenly empty at night. Newspapers reported that the sidewalks were clear, the restaurants half deserted, and the taxicabs idle.”76

Authorities tightened the restrictions, prohibiting all public gatherings that weren’t seen as essential to the war effort. Saloons, poolrooms, and bowling alleys were allowed to stay open, though, as long as they were properly ventilated.77 The number of flu cases dropped at the end of October, and public places were allowed to reopen—with movie houses north of Diversey Avenue resuming business on October 30.78

By the time all of the restrictions were lifted on November 16, Chicago had experienced 38,000 cases of influenza and 13,000 cases of pneumonia in eight weeks.79 “Yet, despite these staggering numbers, Chicago actually did fairly well for a city of its size,” the Influenza Encyclopedia says, comparing the city with others during the pandemic.80

October 1918 had the highest recorded death toll for any month in Chicago history, with 10,249 people dying of all causes. That more than doubled the previous record. Throughout the year, 6,971 Chicagoans died from influenza, and another 2,932 died from bronchitis and pneumonia. The city recorded a total of 44,605 deaths from all causes in 1918.81 (For comparison, 25,769 people died in Chicago during 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit.82)

As the Riviera reopened, one of its ads assured the public: “Our ventilating system provides a steady flow of fresh air.”83 Another said: “An even distribution of fresh washed air prevails at the Riviera.”84 The following summer, an ad said the Riviera had “the only air refrigerating system in theatrical use,” promising: “It is always refreshingly cool during afternoon and evening performances.”85

The show goes on

In those early years of the Riviera Theatre, Chicagoans had their own distinctive pronunciation of the building’s name. According to a 1923 Tribune report, “Most of the Wilson avenue literati refer to the Riviera as the ‘Riveera,’ accent on the ‘e’s.’”86

A.J. Balaban seemed to revel in overhearing people pointing out his family’s name on the sign, as he recalled in his 1942 memoirs:

One rainy night, I was waiting with an umbrella on the corner of Lawrence and Broadway for my wife, who was coming on the street car. A stranger standing in the same doorway said, “See that sign up there—Balaban & Katz? I know ’em well. Great guy, that Abe Balaban. He’s one of my best friends.” Not recognizing him as anyone I had ever seen before, I hid me and my astonishment under my umbrella.

Another time I got to talking to the motorman on a Broadway street car which had stalled in view of the same Riviera sign. “See that new theatre up there? Owned by a couple of Greeks—friends of mine, worth MILLIONS!” And there I was, riding street cars because our money was not yet plentiful enough to warrant taxis. But it didn’t matter. What I wanted was the assurance that the people liked the show, got their refreshment and satisfaction when they came. Friends used to say, “I can’t understand it. I never can get into the Riviera without waiting. There’s always a line a block long.” And I’d answer fervently, “I hope it never changes, as much as I like you.”87

When Balaban heard that person saying, “Owned by a couple of Greeks—friends of mine, worth MILLIONS!” that may have been a reference to Tom Chamales and his brothers (although Tom was actually the only one listed in the property records). Balaban & Katz were the public faces of the Riviera—the team running the theater. But Tom Chamales was the building’s owner.

The Commission on Chicago Landmarks’ invaluable report on the Uptown Square District incorrectly said that “the Chamales Brothers (of Green Mill fame), sold the [Riviera] property to theater operators Balaban & Katz due to financial trouble.”88 In fact, Balaban & Katz merely took over the lease.

It could be true that Chamales’s finances were on shaky ground at times. In January 1919, he signed a quit claim for the Riviera building property, apparently turning over the ownership to a bank auditor89 named Charles H. Gekler.90 But then, in April 1920, Gekler signed a quit claim of his own, turning the property back over to Chamales. It’s unclear what exactly was going on with these transactions, but perhaps Chamales was paying off a debt on the property.

Cook County property records show that Chamales continued to own the Riviera building for another 16 years after that, before finally losing the property in 1936, amid foreclosure and bankruptcy.91 During all of that era’s ups and downs, the rent from the Riviera building was probably a steady source of income for Chamales.

While the Riviera Theatre has lived on as a concert venue, its major local rival in 1918, the Pantheon Theatre at Sheridan Road and Eastwood Avenue, was demolished in 1962.

The Riviera was a steppingstone for Balaban & Katz to build more and more movie palaces. In 1921, the company opened the Tivoli at 63rd Street and Cottage Grove Avenue on the South Side, as well as Chicago Theatre on State Street in the Loop, working again with Rapp & Rapp to design these massive cinemas. Soon after that, Balaban & Katz turned its attention back to Lawrence and Broadway, hatching plans to build yet another castle of cinema near that corner.92

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Footnotes

1 “North Side Hotel Planned,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 12, 1916, part 9, 24.

2 Tract book 587-B, 1-9, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

3 “Plans $650,000 Hotel Building for Broadway,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 11, 1916, 14.

4 Charles Ward Rapp, Rapp & Rapp: Architects (n.p.: Viburnum, 2014), ix, 1, 5.

5 “Edmund R. Krause,” Wikipedia, accessed October 25, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmund_R._Krause; “CIBC Theatre,” Wikipedia, accessed October 25, 2023 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CIBC_Theatre.

6 “The Majestic Theater,” Chicagology, accessed October 25, 2023. Cited source: Architectural Record, June 1906.

7 Charles Ward Rapp, Rapp & Rapp: Architects (n.p.: Viburnum, 2014), 5–8.

8 “Rapp and Rapp,” Wikipedia, accessed June 18, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rapp_and_Rapp.

9 Jeff Lyon, “Saving the Loop,” Chicago Tribune, Sunday Magazine, 14.

10 Rapp, Rapp & Rapp, 21, 23–26.

11 Susan O’Connor Davis, Chicago’s Historic Hyde Park (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 242, https://books.google.com/books?id=yVNl69ZaCV0C&pg=PA242. Cited source: “Gilded Palaces of the Silver Screen,” Chicago Sun-Times, December 8, 1968.

12 Balaban & Katz Historical Foundation, accessed December 5, 2022, http://www.balabanandkatzfoundation.com/

13 Rapp, Rapp & Rapp, 28.

14 Douglas Gomery, “Movie Palaces,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/850.html.

15 A.J. Balaban, as told to Carrie Balaban, Continuous Performance: The Story of A.J. Balaban (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1942. New York: A.J. Balaban Foundation, 1964), 41.

16 Balaban, Continuous Performance, 44. Cited source: Chicago Herald-Examiner, October 1917, reprinted in A.J. Balaban Variety Special, February 27, 1929.

17 Central Park Theater, accessed October 24, 2023, https://centralparktheater.org/.

18 David Balaban, The Chicago Movie Palaces of Balaban & Katz (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2006), 43, https://books.google.com/books?id=gnSkTbgosPAC&pg=PA43.

19 “Air Conditioning American Movie Theatres, 1917-1932. Brunswick-Kroeschell Company,” Heritage Group Website for the Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers, accessed December 5, 2022, http://www.hevac-heritage.org/e-books_large/movie_theatres_USA/ACM_contents-2/2-8BRUNSWICK-KROESCHELL.pdf.

20 “Balaban & Katz,” Chicagology, accessed October 25, 2023, https://chicagology.com/silentmovies/balaban/.

21 Balaban, Continuous Performance, 41.

22 “Plans $650,000 Hotel Building for Broadway,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 11, 1916, 14.

23 “Start New Loop Theater Soon,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 8, 1917, 21.

24 Christine Shang-Oak Lee, “The Revitalized and the Neglected: Rapp and Rapp’s Movie Palaces in Chicago,” Society of Architectural Historians, July 17, 2013, https://www.sah.org/publications-and-research/sah-blog/sah-blog/2013/07/17/the-revitalized-and-the-neglected-rapp-and-rapp’s-movie-palaces-in-chicago.

25 “Building Permits,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 26, 1917, 16; Permit 46038, file 31149, April 25, 1917, Chicago Building Permit Ledgers Reel UID CBPC_LB_18, 130-131 (original 248), Chicago Building Permits Digital Collection 1872-1954, University of Illinois at Chicago Library.

26 “Start New Loop Theater Soon,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 8, 1917, 21; Chicago Daily Tribune, September 30, 1917, part 9, 22.

27 Frederic Hatton, “A Romance of Chicago Theatricals, Chicago Daily Tribune, December 30, 1916, 22.

28 Permit 46038.

29 “The Riviera Theatre History,” Jam Productions, accessed June 20, 2023, https://www.jamusa.com/home/riviera-theatre-history.

30 “Start New Loop Theater Soon.”

31 “Pantheon Theatre,” Cinema Treasures, accessed June 20, 2023, https://cinematreasures.org/theaters/968.

32 Balaban, Continuous Performance, 48.

33 Tract book 587-B, 1-9, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division; “Various Real Estate Matters,” Economist, February 1, 1919, 214. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/osu.32435063389936?urlappend=%3Bseq=219%3Bownerid=13510798902958588-225

34 “Various Real Estate Matters,” Economist, February 1, 1919, 214.

35 Permit 46038.

36 Balaban, Continuous Performance, 48, 49.

37 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, July 24, 1918, 15; advertisement, Chicago Daily News, July 24, 1918, 17.

38 “Former Members,” Chicago Symphony Orchestra, accessed June 21, 2023, https://cso.org/media/o22mmxla/former-members.pdf; Philo Adams Otis, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra: Its Organization Growth and Development, 1891–1924 (Chicago: Clayton F. Summy, 1924), 226, https://archive.org/details/chicagosymphonyo007213mbp/page/226/mode/2up.

39 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, September 11, 1918, 13.

40 “Pantheon Theatre,” Cinema Treasures, accessed June 20, 2023, https://cinematreasures.org/theaters/968.

41 W.K. Hollander, “Motion Picture News,” Chicago Daily News, September 16, 1918, 14.

42 Leslie Midkiff DeBauche, “Film/Cinema (USA),” International Encyclopedia of the First World War, updated June 29, 2017, https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/filmcinema_usa.

43 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, November 4, 1918, 14.

44 “RKO Warner Twin Theatre,” Cinema Treasures, https://cinematreasures.org/theaters/2975; “Rivoli Theatre,” Cinema Treasures, https://cinematreasures.org/theaters/555; “The Riviera Theatre History,” Jam Productions, https://www.jamusa.com/home/riviera-theatre-history, all accessed June 21, 2023; “New Riviera, Chicago, Opens,” Variety, October 11, 1918, 47, https://archive.org/details/Var52-1918-10/page/n25/mode/2up.

45 Erik Lundegaard, “Box Office Stat of the Day: Average Weekly Movie Attendance for the Last 100 Years,” March 12, 2010, http://eriklundegaard.com/item/box-office-stat-of-the-day-average-weekly-movie-attendance-for-the-last-100-years; Cited Source: Alex Ben Block, ed., George Lucas’s Blockbusting: A Decade-by-Decade Survey of Timeless Movies Including Untold Secrets of Their Financial and Cultural Success (2010). “Domestic Movie Theatrical Market Summary 1995 to 2023,” The Numbers, accessed June 21, 2023, https://www.the-numbers.com/market/.

46 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, September 21, 1918.

47 James S. McQuade, “Chicago News Letter,” Moving Picture World, October 5, 1918, 67, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015039589901?urlappend=%3Bseq=73%3Bownerid=13510798884837120-81.

48 Balaban, Continuous Performance, 49.

49 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, October 2, 1918, 15.

50 Balaban, Continuous Performance, 49.

51 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, October 3, 1918.

52 “New Riviera, Chicago, Opens.”

53 “The Riviera Theatre History,” Jam Productions, accessed June 20, 2023, https://www.jamusa.com/home/riviera-theatre-history.

54 “New Riviera, Chicago, Opens.”

55 W.K. Hollander, “Motion Picture News,” Chicago Daily News, September 16, 1918, 14; James S. McQuade, “Chicago News Letter,” Moving Picture World, October 5, 1918, 67, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015039589901?urlappend=%3Bseq=73%3Bownerid=13510798884837120-81.

56 W.K. Hollander, “Motion Picture News,” Chicago Daily News, October 4, 1918, 21.

57 Advertisement, Chicago Daily News, October 4, 1918, 5.

58 “A Woman of Impulse,” IMDb.com, accessed June 21, 2023, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0009834/plotsummary/?ref_=tt_ov_pl.

59 “New Riviera, Chicago, Opens”; advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, November 25, 1918, 19.

60 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, October 5, 1918.

61 “New Riviera, Chicago, Opens.”

62 Balaban, Continuous Performance, 46-47.

63 W.K. Hollander, “Motion Picture News,” Chicago Daily News, October 4, 1918, 21.

64 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, October 3, 1918.

65 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, October 7, 1918, 14.

66 Hollander, October 4, 1918.

67 Balaban, Continuous Performance, 41.

68 Jeff Nichols, “The Maverick at the Center of Chicago’s 1918 Flu Response,” Chicago Reader, May 12, 2020, https://chicagoreader.com/city-life/the-maverick-at-the-center-of-chicagos-1918-flu-response/.

69 “Chicago, Illinois,” Influenza Encyclopedia, accessed June 16, 2023, https://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/city-chicago.html. Cited source: “All Fly Cases Quarantined by Oder of City,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 1, 1918, 1.

70 Influenza Encyclopedia. Cited sources: “Need of Nurses to Combat Flu Grows Urgent,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 4, 1918, 17; “Warning Given City Churches of Epidemic Peril,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 5, 1918, 13.

71 Influenza Encyclopedia. Cited sources: “Public Dancing Barred in Fight on Influenza,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 12, 1918, 5; “You Can’t Smoke on Street Cars till Flu Ends,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 13, 1918, 1.

72 Influenza Encyclopedia. Cited source: “Theaters and Movies Closed by Flu Order,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 15, 1918, 1.

73 Mae Tinée, “Damn the Kaiser!” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 16, 1918.

74 Mae Tinée, “Dr. John Dill Better Look Out for These Chaps!” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 18, 1918.

75 Influenza Encyclopedia. Cited source: “Terms with the Germs,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 17, 1918, 6.

76 Influenza Encyclopedia. Cited source: “Theaters Shut and Lights Off; Loop Is Deserted,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 16, 1918, 13.

77 Influenza Encyclopedia. Cited sources: “Influenza Shuts All Chicago,” Chicago Herald and Examiner, October 18, 1918, 1, and “Cabaret’s Close, Outdoor Games Off, Flu Order,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 18,1918, 13.

78 Influenza Encyclopedia. Cited source: “10 O’clock Limit Put on Slowly Rising Flu Lid,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 29, 1918, 17.

79 Influenza Encyclopedia. Cited source: John Dill Robertson, Report and Handbook of the Department of Health of the City of Chicago for the Years 1911 to 1918 Inclusive (Chicago: 1919), 70.

80 Influenza Encyclopedia. Robertson, Report … 1911 to 1918, 40.

81 Robertson, Report … 1911 to 1918, 1366, 1327, 1426.

82 Number of Deaths by Resident County, Illinois Residents, 2020-2021, Illinois Department of Public Health, https://dph.illinois.gov/content/dam/soi/en/web/idph/publications/idph/data-and-statistics/vital-statistics/death-statistics/Deaths-by-county_2020-2021.pdf.

83 Advertising, Chicago Daily Tribune, October 30, 1918.

84 Advertising, Chicago Daily Tribune, November 1, 1918.

85 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 23, 1919.

86 Al Chase, “Gigantic Movie to Take Place of Green Mill,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 20, 1923, part 9, 30.

87 Balaban, Continuous Performance, 49.

88 Commission on Chicago Landmarks, Landmark Designation Report: Uptown Square District, October 6, 2016, https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/dcd/supp_info/chicago-landmark-designation–uptown-square-district0.html, 21.

89 1920 U.S. Census, Cook, Oak Park, Precinct 4, enumeration district 0145, sheet 7A, Ancestry.com.

90 “Various Real Estate Matters,” Economist, February 1, 1919, 214. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/osu.32435063389936?urlappend=%3Bseq=219%3Bownerid=13510798902958588-226

91 Tract book 587-B, 1-9, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

92 Douglas Gomery, “Movie Palaces,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/850.html.