Chapter 18 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

The war against fun in Chicago reached a milestone in 1918. This was the year when the city’s aldermen voted to outlaw most live music and dancing in any place where alcohol was served.

They took this action—under pressure from moralists denouncing cabarets, booze, and jazz—while state legislatures across the country were voting, one by one, for a national prohibition of alcohol.

World War I put new pressure on Chicago officials to regulate cabarets. The U.S. Navy secretary, Josephus Daniels, complained that sailors at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station in Waukegan were visiting Chicago on leave, running “wild” at cabarets, and returning in a state of intoxication. There were similar concerns about soldiers at the U.S. Army’s nearby Fort Sheridan.1

A federal law made it a crime “to sell any intoxicating liquor, including beer, ale, and wine to any officer or member of the military force, while in uniform.”2 Daniels threatened to shut down every saloon in Chicago as a war emergency measure unless city officials took quick action to stop violations of this law.3

The War Department said soldiers and sailors at training camps were vulnerable to temptations in places like Chicago.

These were young men “who have not yet become accustomed to contact with either the saloon or the prostitute, and who will be at that plastic and generous period of life when their service to their country should be surrounded by safeguards against temptations to which they are not accustomed,” the secretary of war, Newton D. Baker, wrote in his instructions to training camps.4

Some of Chicago’s leading voices against prohibition, including Anton Cermak, threw their support behind a new city ordinance cracking down on cabarets.

“The brewers and the ‘wet’ interests are heartily in favor of abolishing cabarets in connection with the sale of intoxicants,” said the Chicago Brewers’ Association’s attorney, Alfred S. Austrian (the same lawyer who’d helped Tom Chamales win a not-guilty verdict back in 1907, when Chamales was charged with serving alcohol on Sundays).5

“Strangely enough the brewers are chiefly responsible from the stamping out of the alleged cabaret evil in Chicago,” the Associated Press commented. “… They argued that the cabaret was a detriment to the decent saloon and was rapidly crystallizing public sentiment in favor of a saloonless city.”6

Cabaret owners felt betrayed. “The brewers are trying to drive us out of business so that they can sell their products direct to the homes,” said Albert R. Tearney, owner of the Auto Inn at 35th Street and Grand Boulevard, who was a leader in the Chicago Café and Hotel Owners’ Association. “… They are trying to unload this proposition on the public as a patriotic measure.”

Tearney—who said he had support from Green Mill Gardens, Marigold Garden, Edelweiss Garden, and other big cabarets and gardens—threatened to push for the closing of all Chicago saloons and breweries until the war was over.

“Make Chicago dry, and very dry, until the end of the war. We will go out of business,” he said. “These brewers are no more patriotic than a lot of Germans. Take the Liquor Dealers’ Protective Association. It is made up of about 225 saloonkeepers, only a few of them able to talk English. … They were driven in line by the brewers.”

Reacting to Tearney’s spiteful suggestion, Cermak had nothing to say except: “Let ’em rave.”7

On March 26, 1918, the City Council voted 63 to 2 to ban most entertainment in saloons and dramshops, legislation that had been in the works for more than a year.

The only two “no” votes were the First Ward’s aldermen, Bathhouse John Coughlin and Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna, who was himself one of the city’s most legendary saloonkeepers.

Taking effect on May 1, the ordinance outlawed “any exhibition, show, amusement, cabaret, entertainment, act of entertainment, performance whatsoever, whether musical or otherwise” in places serving alcohol. It also prohibited “any dance, or skating, either of patrons or other persons”—suggesting that customers as well as performers were banned from dancing or skating.

But it did make an exception: At certain drinking establishments, “musical selections for the entertainment of the patrons thereof may be played by a musician or musicians on some musical instrument or instruments.” This exception, which required a special permit and a $300 annual license fee, didn’t include vocal music. The idea was to allow only orchestral music in these places with special permits, but no singing.8

The city’s lawyers had argued that the law’s restrictions were justified by the way entertainment had changed it recent years. Entertainment had “broadened out beyond what people had been accustomed to,” they said.

They admitted that the provision allowing instrumental music in some drinking establishments might not work as intended.

This part of the law “would prevent vocal selections which might appeal to the patriotic or religious impulses of patrons while it would permit noisy rag-time, the jangle of the jazz band and the tom tom with which is associated the sinuous oriental dance,” corporation counsel Samuel A. Ettelson and his assistant, Leon Hornstein, wrote.

They hinted about what the city was really trying to accomplish: a law differentiating “between good music which elevates and inspires and bad music which panders to the passions and depraves the appetite.”

But they admitted it might not be possible to write a law making that distinction. 9

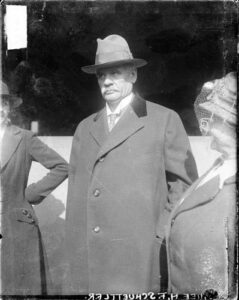

During one debate over the ordinance, police superintendent Herman Schuettler told aldermen: “This ordinance eliminates public dancing, and when you divorce dancing from alcohol, you have gone 90 percent of the distance toward eradication of cabaret evils.”

“But this ordinance would permit jazz bands,” alderman James A. Long said.

“Take away dancing and there would be no use for jazz bands,” alderman James B. Bowler replied.

Alderman John Toman had objected that the provision against vocal music in bars “would prevent a man from singing a song in his own place of business.”10 In spite of such objections, nearly all of the aldermen eventually decided to support the ordinance.

The new law did allow saloons to play music on “any mechanical or automatic musical instrument, like pianola, orchestrion, graphaphone, etc.” In other words, no license was required for record players or player pianos and similar music-making machines.11

The law applied to saloons as well as other places where alcohol was served, such as restaurants and hotels. Singing and dancing were also prohibited at any banquets or weddings held inside these alcohol-serving places. 12

“The ordinance calls for the obliteration of all entertainment from the city’s thirst parlors,” the Chicago Daily News wrote, trying to explain the logic behind the law: “It points out that, whereas a citizen drinking beer is not in vital danger of misbehaving, one drinking beer and further inspired by the lilt of music, the rhythm of dancing, the yodle of feminine voices and the color, in short, of the cabaret is in such danger.”13

The Tribune predicted that Chicago’s nightlife would be sleepy under the new law. “Exhilaration in Colosimo’s resort, the last stand of the sinners, will be reduced to ‘Pagliacci’ rendered soulfully by a string band,” the newspaper remarked. “There will be no dancing, no singing. Soda pop never encouraged a light and frivolous toe. … The Marigold Garden, Tom Chamales’ Green Mill Gardens, and the Reinzi (a beer garden at Clark and Diversey) all are doomed to lay by their dances and singing and restore the fiddles and the horns. The cabaret is dead. What’s the next thrill?”14

“With this law in force Chicago makes another stride toward civic virtue,” the Daily News commented, with perhaps a touch of sarcasm. “The local tango lizard and saxophone king, the merrie danseuse … hit the skids and shoot out of the city’s life.”15

“The jazz bands are hushed and the singers silent,” the Associated Press reported when the law took effect. “The cabaret which had developed into a conspicuous feature of the city’s night life is dead.”

As a result, “several thousand of expert saxophone players, trick drummers, piano players and other musicians are out of work and hundreds of singers are idle.”16

“Where on earth will they go?” asked Daily News critic Amy Leslie. “The shutout leaves hundreds of girls and boys and a regiment of musical brawlers who hatched fun out of the music with the jazz band epidemic.” She called them “Poor butterflies!”17

But as it turned out, Chicago cabarets were far from dead.

With the new law in effect, places like Green Mill Gardens faced a choice: They could serve alcohol without any live entertainment and dancing. Or they could pay $300 for a special permit to allow performances of instrumental music. Or they could continue hosting entertainment but stop serving alcohol. Or perhaps they could figure out a way of serving alcohol in one place, while hosting entertainment and dancing in another place. But would that violate the law?

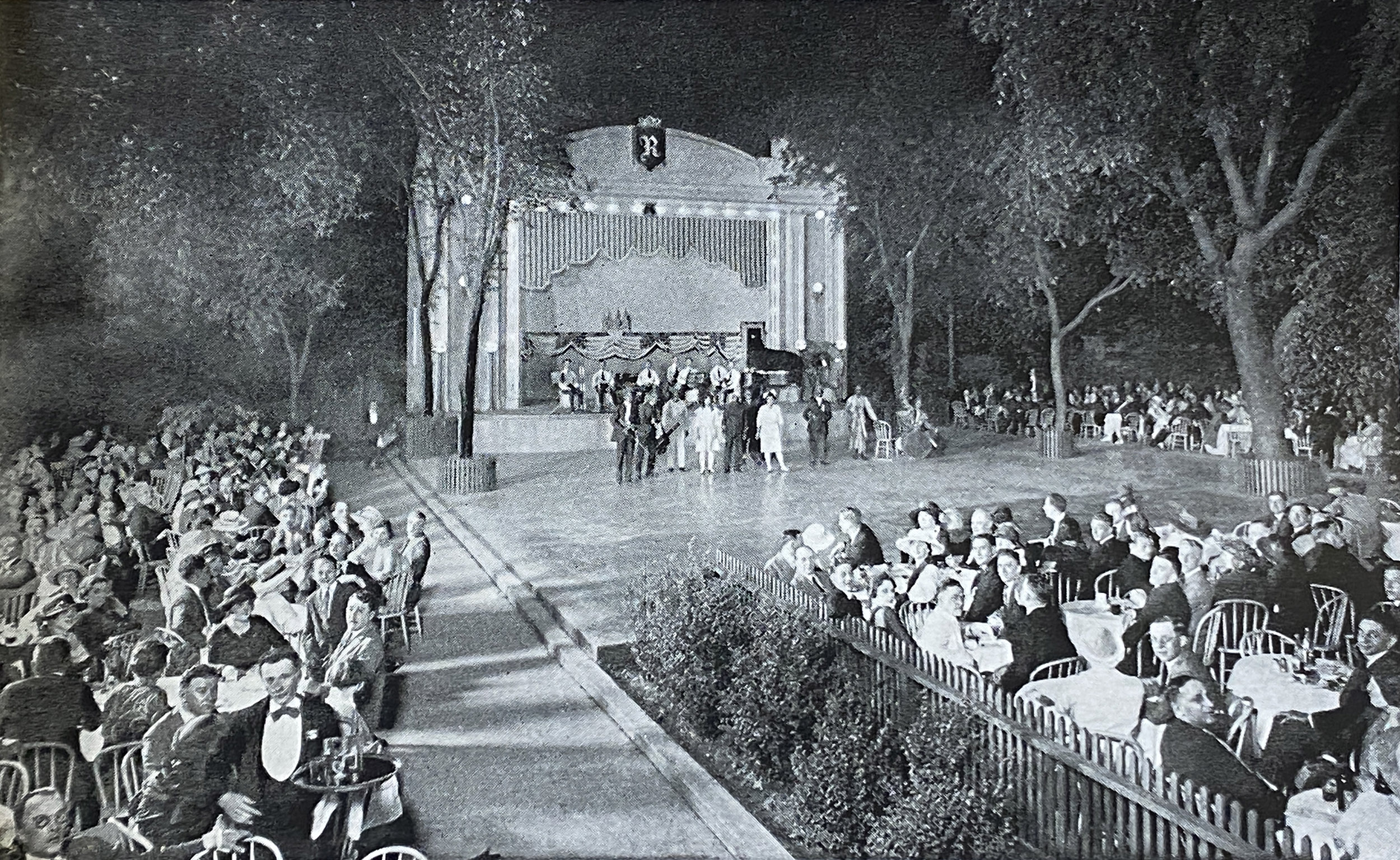

Green Mill Gardens opened its summer gardens for the season on June 28, with an advertisement promising a chance to “Dine and Dance.” The Daily National Hotel Reporter commented: “Artistic decorations, electric displays, massed flower beds, increased orchestras and a music stand are the new features. An illuminated maple tree with 500 incandescent bulbs in the middle of the garden is a charming decoration.”

Arnold Johnson’s Ragadours, a 12-piece band, “played the jazz program.”18

Born in Chicago, Arnold Johnson had played piano in a Chinese restaurant when he was 14 and later worked as an accompanist for vaudeville revues. He’d studied at the Chicago College of Music and the American Conservatory of Music.19 At times, his group—which played often at Green Mill Gardens in 1918 and 191920—was billed as a “Jass Dance Orchestra”21 or as Arnold Johnson’s Famous Jazz Ragadours.22

Joe Kayser, a drummer and future bandleader who was serving in the U.S. Navy during World War I at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center near Waukegan, often went into the city with his service buddies to visit Green Mill Gardens, where they’d see Arnold Johnson’s band playing for the dancers.23

Johnson also ran a small booking agency, lining up musical acts for Green Mill Gardens and other venues.24 And he played piano in drummer Tommy Rogers’s 10-piece orchestra, another regular Green Mill Gardens band in the years from 1918 to 1920. That group included New Orleans cornetist Ray Lopez and some notable musicians who went on to become bandleaders: Isham Jones, Maurie Sherman, Sig Meyer, and Sol Wagner.25

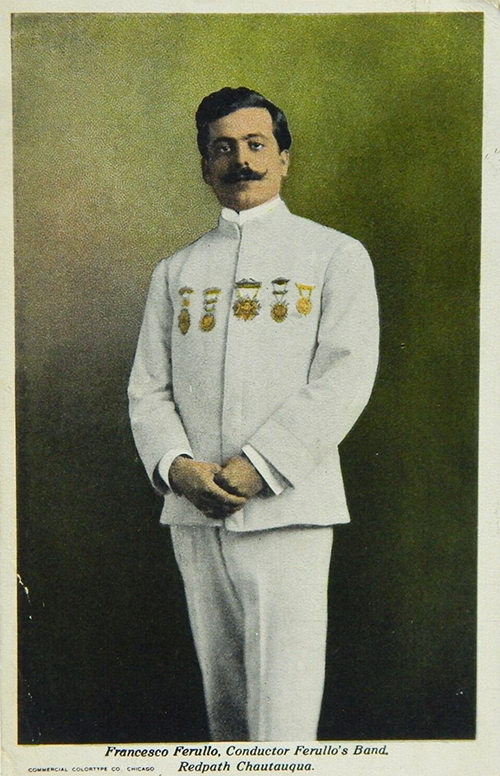

On the evenings when Arnold Johnson’s Ragadours played at Green Mill Gardens, the entertainment also included Francesco Ferullo conducting a band of 35 musicians playing popular and classical music.26

At the time, Americans were fascinated by the dramatic gestures of Italian conductors like Ferullo, who demonstrated fervor at the podium. The Los Angeles Times had described Ferullo’s style as “picturesque” and graceful, with “lightness and delicacy,” noting how he’d often “brought audiences to their feet in wild applause.”27

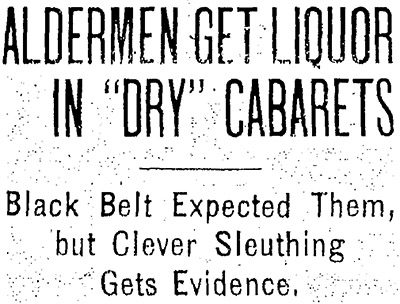

When some aldermen visited Green Mill Gardens in late June 1918, shortly after it opened for the season, they found “a thoroughly dry establishment where an orchestra plays and dancing takes place, while the gardens just outside are as wet as they can be, even when there are not clouds in or on its ‘roof,’” the Tribune reported.

The Broadway Inn, at Broadway and Devon Avenue, served drinks in one room, where music was performed. But the proprietor had also leased a space next door, turning it into a room for dancing.

Across the street, the Sheridan Inn was serving drinks inside, while people danced on a porch. Elsewhere, the Athenia Café, at 1521 North Clark Street, placed a thin partition down the middle of the place. Music and drinks were on one side, dancing on the other. Summing up these observations, a Tribune headline said: “‘Skeeter-Bar’ Partitions Beat the Cabaret Law.”28

The city’s lawyers had anticipated some of these creative solutions. As they’d explained earlier, “The ordinance would prevent dancing and all other entertainments except instrumental music at such places as the Edelweiss Garden, Bismarck Garden, and other so-called summer gardens, unless the place where the dancing is conducted is entirely distinct from the enclosure in which the dramshop is located.” 29

Other establishments stopped serving alcohol, but let customers bring in their own booze. City officials vowed to crack down on this practice, saying it was a crime to allow customers bring in “hip liquor.”30 Meanwhile, other supposedly dry cabarets were actually serving alcohol, even though they didn’t have liquor licenses.

“The anti-cabaret ordinance has not done what it was intended to do,” alderman John Toman said. “Instead of separating dancing, cabarets, and liquor, as was intended, these things are still together. Some of the dry cabarets in the city are worse than anything we ever had when we had wet cabarets.”31 He added, “Many of these places don’t open up until 1 a.m. Something must be done to stop them.”32

The acting police chief, John Alcock, told aldermen that the dry cabarets were “running wild.”33 Some of them had all-night dancing, he said.34

Alcock (filling in for the ailing superintendent, Herman Schuettler, who would die in August) warned that “diseased immoral women” were mingling with soldiers and sailors in dry cabarets.35

Alcohol could still be served at dance events, which could run as late as 3 a.m., as long as the organizers had a special bar permit.

But Commonwealth Edison tycoon Samuel Insull, who was chairman of the State Council of Defense, criticized Chicago for issuing these permits to “irresponsible organizations, many of which are of questionable character.”

In a letter to Mayor Thompson, Insull wrote: “These so-called social organizations hold dances which, in a great many instances, descend to mere orgies. During the last few months, soldiers and sailors visiting Chicago have attended a number of these dances, and liquor has been sold to a number of them, and we have had reports showing that men in uniform were found in these places, under the influence of liquor.”36

In the face of these criticisms, the City Council voted to suspend special bar permits.37

Some aldermen said the anti-cabaret law should be repealed.38 But instead, the City Council voted to make one small tweak in the law, removing the ban on skating.39

Perhaps the aldermen were trying to help out the Sherman Hotel’s College Inn and the Morrison Hotel’s Terrace Garden—both of which featured professional skaters performing on ice in the midst of the diners.40

The council approved another law on August 14, 1918, regulating “dry cabarets”—or as the ordinance called them, “public places of amusement”—and requiring these places to stop all entertainment and dancing at 1 a.m.

The law defined these places as “any building, hall, room or inclosure to which the general public may be admitted without the payment of an admission fee, or charge of any kind or character where they may engage in or witness the performance of any amateur theatrical entertainments, any exhibition, show, amusement, cabaret, entertainment, whether musical or otherwise, or any dance or skating either of patrons or other persons.”

To host live entertainment, these venues needed to get a license from the city, with annual fees from $25 to $100, depending on size. The mayor could reject a license applicant if the building wasn’t a “fit or proper place” or if the planned entertainment was deemed “immoral or dangerous.”

The ordinance passed by a vote of 49 to 5. Coughlin was one of five “no” votes; Kenna didn’t vote.41 (This 1918 law was an early version of a city ordinance that’s still in effect, requiring nightclubs, concert venues, and various other entertainment venues to get a Public Place of Amusement license.42)

With this new ordinance, city officials essentially declared that the city would shut down every night at 1 a.m., at least as far as drinking, dancing, and live music.

That summer, authorities alleged that the local waiters’ union had attacked Green Mill Gardens with a stench bomb.

Unions representing waiters and bartenders had been complaining since 1916 that Chamales refused to deal with them.43 “Stench bombs were used at … banquets when the managers refused to unionize,” a prosecutor said. In one of these incidents, “the odor became so strong from the bomb that women fainted.”

Ten people were indicted in the scheme—not just for using stench bombs, but also for drugging restaurant and hotel patrons by slipping “Mickey Finn” powders into their drinks. This was one of the first times—perhaps the first time—that “Mickey Finn” was used as slang for lacing drinks with an incapacitating agent such as chloral hydrate. The practice took its nickname from a Chicago saloonkeeper who’d made headlines for doing it back in 1903.44

On August 30, 1918, Green Mill Garden hosted a show to benefit the Chicago Daily News’s Tobacco Fund, which was sending cigarettes to American troops in Europe. (It would eventually raise more than $50,000 for this cause.45)

The stars of the show were the Dolly Sisters, identical twins who’d caused a sensation when they debuted in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1911. Known on stage and screen as Jenny and Rosie Dolly, they’d been born in Budapest as Janka and Rózsika Deutsch.

In 1918, they would appear in together in a movie inspired by their lives, The Million Dollar Dollies. Jenny was the wilder sister, often making news with her romances, gambling exploits, automobile accidents, and vast quantities of jewelry. “I have never seen so many jewels on any one person in my life,” the Viscountess Furness once said about her.46

When the Dolly Sisters appeared at Green Mill Gardens, they were joined by Jenny’s husband at the time, Harry Fox, a dancer who’d helped to popularize the foxtrot. (The etymology is disputed, but some stories say the dance was named after Harry Fox.) 47

Fox told the crowd that he’d give $10 to the Tobacco Fund, for the honor of dancing with his wife. As he started to pirouette with Jenny, a man in the crowd yelled out: “How can you tell which is your wife?”

Fox stopped the music. “Just to be sure that I haven’t made a mistake, I’ll give another $10 to dance with my wife’s sister,” he said. Rosie stepped forward, took the other $10, and finished the dance with him.

“It was the spark that set the crowd ablaze,” the Daily News reported. “Men gave $10 to dance with their own wives, and said that it was the best dance they had ever had with them.” Money was also showered on the Dolly Sisters for nearly three hours, as men vied for the chance to dance with one of the twins.

At one point, Fox stepped into the center of the floor, raised his hand, and whistled the orchestra into silence.

“I have found a woman who will give $5 to dance with Tom Chamales, owner of the Green Mill Garden,” he said. One of the twins held the $5. Chamales stepped out onto the floor to dance with her.48

The Daily News headline about this charity dance, “Dance With Wife, $10,” brings to mind the lyrics Fred Fisher wrote four years later for his song, “Chicago (That Toddlin’ Town)”:

They have the time, the time of their life

I saw a man, he danced with his wife

In Chicago, Chicago, my hometown.

Reports quickly surfaced about Chicago venues breaking the new laws against late-night fun.

“Chicago Thrown Open to Vice in Defiance of U.S.,” a Tribune headline declared. “Laws Flouted Under Eyes of Police in All Night Orgies.” The newspaper sent reporters into numerous cabarets on the night of Saturday, August 30, and the early morning hours of that Sunday, and they witnessed numerous violations of the law.

They didn’t find much to report at Green Mill Gardens, though. “The tables were nearly deserted at 1:20 a.m.,” they wrote. “Dancing had stopped and the waiters were clearing away. A dozen couples remained drinking and eating.”

But the Committee of Fifteen, a private organization campaigning against vice in Chicago, sent out its own investigators on the same night.

“I counted twenty-four sailors and nineteen soldiers present,” an investigator reported after visiting Green Mill Gardens. “Many of them were drinking what appeared to be intoxicating liquors. In most cases they sat with one or more civilians. Although apparent that the men in uniform would order soft drinks they were drinking the intoxicating liquors ordered by their companions. I saw two sailors sitting with two known women of the street.”

Several blocks away, a female reporter for the Tribune saw a “young girl” stumbling out of Rainbo Garden on Clark Street (pictured above). “Her cheeks were highly flushed and her brown eyes sleepy from the effects of liquor,” she wrote. The woman giggled and said, “I’ll fall if I go any farther.”

As the drunk woman went back inside, the reporter followed her and asked, “Can you get a drink for me?”

The woman took her by the arm, leading her to a waiter. “Here, No. 21,” she said, catching the waiter by the coat lapel as she swayed a little. “I want you to get this girl a drink.”

The reporter ordered a Scotch whisky, and the waiter brought one out, charging her 40 cents. The reporter noted that it was 1:45 a.m. on a Sunday, a time when it was illegal to serve alcohol.49

The investigators counted servicemen at other popular venues around Chicago that night: Marigold Gardens had 33 sailors and 28 soldiers. Colosimo’s had eight sailors in uniform and six soldiers, with “two men in uniform half drunk.”

And at the South Side’s Pekin Café, the investigators reported seeing “soldiers and sailors, white drug users, and blacks found mixing indiscriminately.”50

Officials at the State Council of Defense were incensed by Chicago’s lax enforcements of laws. These Illinois state officials reportedly discussed taking over the Chicago Police Department, removing it from the city government’s control.51

Alcock, the acting police chief, lectured his department’s captains, urging them to crack down.

“It makes no difference whether it is a ‘wet cabaret’ with a ‘dry space’ set aside for dancing or for singers,” he said. “There can be neither dancing or singing without a ‘dry cabaret’ license, and these places haven’t got them.”52

Alcock also issued an order shutting down all-night movie theaters, which had been outlawed along with other early-morning entertainment.

After some initial hesitation, Green Mill Gardens, Rainbo Garden, Marigold Garden, Edelweiss Garden, and the city’s other major gardens and cafes applied for licenses to operate as dry cabarets—essentially promising they wouldn’t serve alcohol in the same spaces where they presented entertainment and where people danced, and that they’d close at 1 a.m. every night.53

By the end of 1918, the city had received $2,550 in license fees for dry cabarets. (The fees were on a sliding scale, so that total could represent anywhere from 25 to 102 places with licenses.)54

Green Mill Gardens continued to surface in newspapers for a variety of reasons. A few of the incidents from 1918:

— Classified advertisements occasionally appeared about things people had lost at Green Mill Gardens, including rings and jewelry. In July 1918, someone complained about the theft of a fox throw from a chair inside the venue. The advertiser said the thief’s identity was known. “Immediate return is necessary to avoid prosecution. No questions asked. No leniency will be shown after July 3.”55

— On the night of August 23, people heard a woman’s “wild screams of anguish and fear” near Green Mill Gardens. The next day, the estranged wife of former congressman Frank Buchanan confessed that she was responsible. She told the Tribune that she’d attacked her husband and his secretary, who was rumored to be his mistress.

“Yes, I made ’er scream, with my little fist I made her scream,” Mrs. Buchanan said. “I took her by the throat and slapped her face. Then I snatched my umbrella away from my husband, who was with her, and I got in a few good licks with that. O yes, I hit him a couple of times with it, too, just for luck and good measure.”56

— In October, a man in the crowd at Green Mill Gardens, A.J. Pierce, reported another audience member for making pro-German comments. Pierce said he’d overheard Gustav Myers, an insurance actuary, remark: “The kaiser is a fine man. He has a lot of brains. He is all right. … Anyone who knocks the kaiser in order to sell Liberty bonds is all wrong. I know the kaiser and his whole family, and he’s the smartest man I ever met.”

Hearing that, Pierce said, “That fellow ought to be pinched.” The next time he saw Myers at Green Mill Gardens, he alerted the police, who hauled away Myers to face an examination by federal agents. It’s unknown whether the government took any action against Myers.57

At 1:55 a.m. on Monday, November 11, 1918, an alert from the Associated Press arrived in Chicago’s newsrooms: “Armistice signed.”

In the streets, policemen started yelling, “The war is over! The war is over!” Sirens blared from the city’s fireboats and newspaper buildings. People poured into the streets to celebrate—a party that began in the early morning hours and lasted more than 24 hours, with the crowd size estimated at a million.

“From one end of the city to another, everything was turmoil,” the Daily News reported. “Its millions of citizens gave themselves without bounds to the delirium of joy the news of the war’s grand finale had evoked in them. Pandemonium was in the saddle wherever its citizens congregated.”

The Loop was the center of the raucous festivities, but it wasn’t the only place that went wild. Up on the North Side, a couple of blocks south of Green Mill Gardens, a bonfire at Wilson Avenue and Broadway attracted more than 500 people around 4 p.m. Tuesday.

By the end, nine people had died and 30 were injured during the celebrations, largely from automobile accidents and accidental shootings. The police commented that the crowds were generally well-behaved.58

In late December 1918, news surfaced about financial troubles for Catherine and Charles Hoffman, who owned the land where Green Mill Gardens stood.

They were being sued by Charles K. Anderson, who held first and second mortgages on their properties along Broadway, totaling $95,000. He was also trying to recover $6,000 he’d paid to redeem the property after the taxes on it weren’t paid.

Anderson asked for foreclosure. He alleged that the Hoffmans were having trouble paying their bills because Green Mill Gardens was hurt by “the government’s restrictions on the sale of liquor and the impending prohibition of its sale.”59

Tom Chamales told reporters that Green Mill Gardens itself wasn’t the lawsuit’s target. “The foreclosure runs against the property upon which it is situated, and not against our property,” he told the Tribune. “The suit will not affect our business, which will continue as heretofore.”60

Chamales told the Daily News: “The Green Mill Gardens are in no way involved in the proceedings, nor am I, except as the guarantor of a $60,000 note made by Mr. and Mrs. Charles Hoffman, owning the property. The buildings that I have erected on the property are worth far in excess of the amount of the note. As for the business of the gardens, it was never in a more flourishing condition.”61

A judge ordered that the property be put up for public auction on March 29, 1919. Frederick A. Hastings made the highest bid, $102,000, but the Hoffmans were given 15 months to redeem the property.62 They paid the necessary money, and certificates of redemption were filed with the county on February 17, 1920, showing that the Hoffmans again held a free and clear title to the land.63

While all of this was going on, the Hoffmans faced similar litigation over their properties at the west end of Green Mill Gardens, and they ended up getting a special warranty deed, showing that they owned the land free of any liens.64

The financial woes for the Green Mill Gardens property seemed to be over. For the time being, anyway.

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Footnotes

1 “New Edict Ends All Liquor Carrying Here,” Waukegan Daily Sun, July 26,1918, 1, 7.

2 Journal of the Proceedings of the City Council of the City of Chicago, vol. 85, April 22, 1918, 2524–2525, https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofcit85chic/page/n1143/mode/2up.

3 “Wets to Curb Cabarets and Protect Bars,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 24, 1918, 1–8.

4 City Council, 2524–2525.

5 “Wets to Curb Cabarets and Protect Bars.”

6 Associated Press, “All Cabarets in Chicago Close; Brewers Cause,” (Mount Vernon OH) Banner, May 14, 1918, 6.

7 “Threat of Dry Town Made by Cabaret Men,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 26, 1918, 17.

8 City Council, vol. 85, March 26, 1918, 2510–2511, https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofcit85chic/page/n1133/mode/2up.

9 City Council, vol. 85, November 19, 1917, 1476-1480, https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofcit85chic/page/n103/mode/2up.

10 “Divorce Dance and Drink,” Chicago Daily News, December 7, 1917, 1.

11 City Council, vol. 85, March 26, 1918, 2510–2511.

12 City Council, vol. 85, November 19, 1917, 1476-1480.

13 “Cabaret Men at Sea; Lid on Monday Night,” Chicago Daily News, May 4, 1918, 3.

14 “Revelry by Night Is Put to Sleep in City’s Cafes,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 24, 1918, 8.

15 “Cabaret Men at Sea.”

16 “All Cabarets in Chicago Close.”

17 Amy Leslie, “Tearful Obsequies of Cafe Cabarets,” Chicago Daily News, May 11, 1918, 10.

18 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 23, 1918, 14; “Amusement Notes,” Daily National Hotel Reporter, July 1, 1918, 1.

19 “Arnold Johnson (musician),” Wikipedia, accessed June 5, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arnold_Johnson_(musician).

20 Advertisement, Chicago Daily News, May 29, 1918, 15; “Amusement Notes,” Daily National Hotel Reporter, July 1, 1918, 1.

21 Advertisement, Chicago Daily News, February 21, 1919, 26.

22 Advertisement, Chicago Daily News, June 25, 1919, 24.

23 Charles A. Sengstock, That Toddlin’ Town: Chicago’s White Dance Bands and Orchestras, 1900–1950 (Urbana: University of Illinois, 2004), 62. Cited source: Tape-recorded interview by author, Chicago, May 12, 1976.

24 Sengstock, That Toddlin’ Town, 17.

25 Sengstock, That Toddlin’ Town, 62.

26 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 23, 1918, 14; “Amusement Notes,” Daily National Hotel Reporter, July 1, 1918, 1.

27 Mike Brubaker, “An Atlantic City Love Story, Part 2,” Temposenzatempo, August 3, 2019, https://temposenzatempo.blogspot.com/2019/08/an-atlantic-city-love-story-part-2.html.

28 “‘Skeeter-Bar’ Partitions Beat the Cabaret Law,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 29, 1918, 5.

29 City Council of the City of Chicago, vol. 85, November 19, 1917, 1476-1480.

30 “City Is Hep to ‘Hip Liquor’: To Hop On It,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 13, 1918, 11.

31 “Council Asked to Repeal Law Against Cabaret,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 21, 1918, 17.

32 “Cabaret Bunk,” Chicago Eagle, May 25, 1918, 1.

33 “In the City Council,” Chicago Eagle, June 1, 1918, 1.

34 “Alcock Seeks Right to Rule ‘Dry’ Cabarets,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 28, 1918, 6.

35 “Diseased Women Lure Draft Men, Alcock Charges,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 29, 1918, 15.

36 City Council, vol. 85, April 22, 1918, 2524–2525, https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofcit85chic/page/n1143/mode/2up.

37 “Cabaret Men Seek Loopholes in Law,” Chicago Daily News, May 7, 1918, 19.

38 “Council Asked to Repeal Law Against Cabaret,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 21, 1918, 17.

39 City Council, vol. 86, August 14, 1918, 956-957, https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofcit86chic/page/956/mode/2up.

40 Ryan Stevens, “Cocktails in Chicago: The College Inn and Terrace Garden Ice Shows,” Skate Guard Blog, May 26, 2020, https://skateguard1.blogspot.com/2020/05/cocktails-in-chicago-college-inn-and.html.

41 City Council, vol. 86, August 14, 1918, pp. 960-963. https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofcit86chic/page/960/mode/2up.

42 Municipal Code of Chicago, Published by Order of the City Council, 1990, Current through Council Journal of March 30, 2023, American Legal Publishing, https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/chicago/latest/chicago_il/0-0-0-2634195.

43 Fred Ebeling, “Liberty,” Day Book, July 10, 1916, 25; “What Our Organizers Are Doing,” The Mixer and Server 25, no. 8 (Aug. 15, 1916), 18, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/wu.89062146725?urlappend=%3Bseq=500%3Bownerid=13510798892482331-504.

44 “Ten Indicted in Diabolisms of ‘Mickey Finn,’” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 9, 1918, 8.

45 “Writes Thanks for ‘Smokes,’” Chicago Daily News, February 5, 1919, 3.

46 Jack Backstreet, “Jenny Dolly,” IMDb.com, accessed June 15, 2023, https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0231184/bio/?ref_=nm_ov_bio_sm; “Dolly Sisters,” Wikipedia, accessed June 15, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dolly_Sisters.

47 “Harry Fox,” Wikipedia, accessed June 15, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Fox; “Foxtrot,” Wikipedia, accessed June 15, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foxtrot.

48 “Dance With Wife, $10,” Chicago Daily News, August 31, 1918, 1.

49 “Chicago Thrown Open to Vice in Defiance of U.S.,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 2, 1918, 13.

50 “Stop Chicago’s Vice, Daniels Tells Moffett,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 12, 1918, 15, 16.

51 “State Council to Join With Moffett in Vice Crusade,” Waukegan Daily Sun, September 13, 1918, 9.

52 “Clamp Down Lid or Quit, Alcock Warns Captains,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 15, 1918, 17.

53 “Council Takes Hand in Probe of Vice Status,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 18, 1918, 14; “All Night Movie Ban,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 17, 1918, 13.

54 Eugene R. Pike, Sixty-Second Annual Report of the Comptroller of the City of Chicago, for the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 1918 (Chicago: W.J. Hartman, 1919), 103, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101067482339?urlappend=%3Bseq=109%3Bownerid=27021597768244010-117.

55 Classified advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, July 4, 1918, 25.

56 “Those Screams? Oh, a Wife Got an Eye on Her Rival,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 25, 1918, 5.

57 “Gustav Myers Hauled in as Kaiser Booster,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 21, 1918, 17.

58 “100 Years Ago: Chicago Celebrated the End of WWI,” Chicago Public Library, October 23, 2018, https://www.chipublib.org/blogs/post/100-years-ago-chicago-celebrated-the-end-of-wwi/; Alison Martin, “This week in history: Chicagoans Let Loose on Armistice Day,” Chicago Sun-Times, November 11, 2020, https://chicago.suntimes.com/2020/11/11/21561306/this-week-in-history-chicago-armistice-day.

59 “Green Mill Garden Target,” Chicago Daily News, December 21, 1918, 1; “‘Green Mill’ in Court on Suit to Foreclosure,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 22, 1918, 17.

60 “‘Green Mill’ in Court on Suit to Foreclosure,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 22, 1918, 17.

61 “Gardens Are Not Involved,” Chicago Daily News, December 24, 1918, 5.

62 Document 6493085, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

63 Tract Book 543 A-2, 218, 225, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

64 Tract Book 543 A-2, 249, 251, 254, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division; The National Corporation Reporter 55, no. 16 (November 22, 1917), 619, https://books.google.com/books?id=xJFDAQAAMAAJ&lpg=PA619.