CHAPTER 41 of THE COOLEST SPOT IN CHICAGO:

A HISTORY OF GREEN MILL GARDENS AND THE BEGINNINGS OF UPTOWN

PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER

The Green Mill kept going out of business, but it never stayed dark for very long. As 1927 ended, the nightclub seemed to be in trouble. It had lost its big star, Joe Lewis, and the crowds he’d been attracting. And the Green Mill was reportedly connected with a brutal attack that nearly killed Lewis—not the sort of publicity that would help business. In December, the Green Mill closed its doors. The explanation? “Business terrible,” Variety reported.1

But seven weeks later, it reopened under a new owner, Ralph Burke, featuring music by Henri Gendron’s orchestra. “Refined vaudeville acts are part of the entertainment. Only dinner charges are made,” the Uptown Citizen reported, implying that there was no cover charge.2

Burke was also the proprietor of the White House Inn on the city’s western outskirts, near Irving Park and River Roads (where he would soon be arrested for allegedly selling beer).3 He formed a new corporation called Green Mill Gardens Inc., and he owned one-fourth of its $10,000 in stock. Accountant William B. Mierz, who’d been involved with various versions of the Green Mill over the years, also owned a fourth of the company.

But oddly enough, the biggest shareholder was supposedly 20-year-old Edith L. Johnston,4 who lived in Berwyn. It’s unclear exactly how this young single woman was connected with the Green Mill, but corporation documents filed with the State of Illinois showed that she owned $5,000 of the company’s shares. By the time the U.S. census was conducted two years later, she’d gotten married and was working as a stenographer in a law office.5 It’s hard not to wonder if she was a front for someone else’s ownership in the joint.

That wasn’t the only curious thing about this latest incarnation of the Green Mill. The Chicago Defender, the city’s leading newspaper for African Americans, reported that an all-Black orchestra and revue would be featured as the Green Mill’s regular entertainment. The venue’s new managing director was reportedly Martin B. Paley, who’d been the owner of the Café de Paris, a black-and-tan cabaret on the South Side.6 The Green Mill’s floor shows would be overseen by Lawrence Deas, who’d produced the popular all-Black revue Plantation Days at Green Mill Gardens in 1922.

Dave Peyton, a Black musician who wrote columns for the Defender,7 announced that he was assembling a 12-piece orchestra to play at the Green Mill. “Both orchestra and show will be Race artists,” Peyton wrote, noting how unusual it was for African Americans to perform at this North Side venue. “The Green Mill has had only one Race orchestra during its regime,” he wrote, referring to the New Orleans–born violinist Charles Elgar’s Syncopated Band. “Elgar and his bunch played there about six years ago with the ‘Plantation Days’ show and ever since white units have held the job,” Peyton commented.

“The Green Mill is on the far North side and in the heart of the Gold Coast district,” Peyton continued. He was using “Gold Coast” as a term for wealthy areas along the lakeshore, not the specific neighborhood known today as the Gold Coast. The Green Mill’s location in Uptown presented a challenge for Black musicians who dared to venture into the area. And Peyton offered some advice for musicians who might decide to join up with his group: “Our musicians should remember that they will be watched and criticized. If you be careful of your conduct in the place and out of it your services will be appreciated, but if you pull some of the nasty tricks attributed to our gang, the job will not last long for you.”8

But the Defender did not write again about these plans for an all-Black show at the Green Mill. I haven’t found any coverage about it in other Chicago newspapers, either. Did the shows ever happen? That’s unclear.

Such plans may have met resistance from some of Uptown’s white residents and merchants. That same year, local residents began circulating a document designed to keep Black people out of Uptown. The neighborhood’s business group, the Central Uptown Chicago Association, urged property owners to sign a covenant, agreeing that “no part” of their premises “shall be sold, given, conveyed or leased to any negro or negroes, and no permission or license to use or occupy any part thereof shall be given to any negro except house servants or janitors or chauffeurs employed thereon…”

By the time the covenant was filed in Cook County’s land records in 1931, it encompassed 91 properties in the vicinity of Broadway and Lawrence Avenue—including the Green Mill building. Tom Chamales, the man who’d created Green Mill Gardens and continued to control the property, put his signature on these race restrictions.9 (During that era, many white Chicagoans used racially restrictive housing covenants to prevent Black people from moving into their neighborhoods. In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court would rule that these covenants cannot legally be enforced.10 The Chicago Covenants project is now searching through Cook County’s old property records to document which local properties had such race restrictions.)

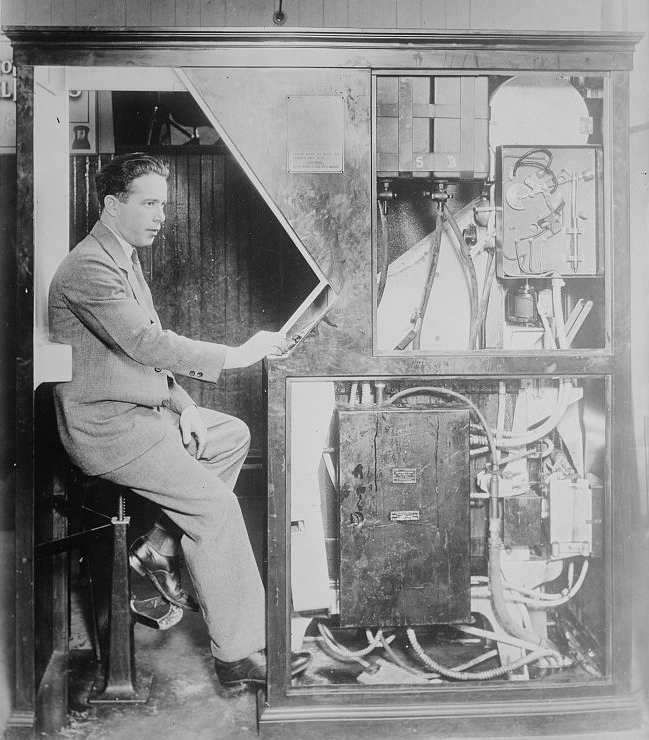

The early 1928 iteration of the Green Mill did not last long, and the nightclub was soon defunct again. On April 29, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported that Middle West Photomaton was leasing 4806 North Broadway—the Green Mill’s entrance and lobby—and turning the space into a shop featuring a newfangled invention.11 The Photomaton had already been a sensation in New York City. By putting 25 cents into a slot, customers could get eight photos of themselves—in eight different poses—within eight minutes. It was one of the earliest versions of what came to be known as photo booths. Henry Morgenthau Sr., a former U.S. ambassador to Turkey, made headlines when he paid $1 million to the Photomaton’s inventor, Anatol Josepho. “I believe that … we can make personal photography easily and cheaply available to the masses of this country,” Morgenthau said, announcing his plans to open Photomaton shops across the country.12

A sign for the photo shop at 4806 Broadway was visible when the Tribune took a photo of the building in 1928.

View this post on Instagram

A banner draped across the Green Mill’s former entrance proclaims the spot as the Photomaton’s “New Uptown Home,” while attempting to entice passersby with an offer of “8 pictures in 8 poses in 8 minutes.”13

Middle West Photomaton also appeared at 4806 Broadway in a 1928 reverse-street directory, which listed the occupants at every address in Chicago. This book offers evidence about what else was located in the building at that time. Soda fountain manager Frank Pendergast14 and cigar dealer M.B. Seigel were listed at 4800 Broadway, the corner drugstore. Wolf’s Jewel Shop was next door, at 4802 (the spot where the entrance to the modern-day Green Mill jazz club is today).

Another door at 4802 Broadway led up to rooms on the second floor: the Gypsy Tea Cup Inn restaurant; physicians Eva Conheim, Herbert Rattner, and Edw. Sager; dentist S.L. Rubens; tailor C.F. Gustafson; the Vollrath Dancing School; Knipp & Shapiro real estate; and the office of Tom Chamales, the building’s longtime overseer, and his brother William.

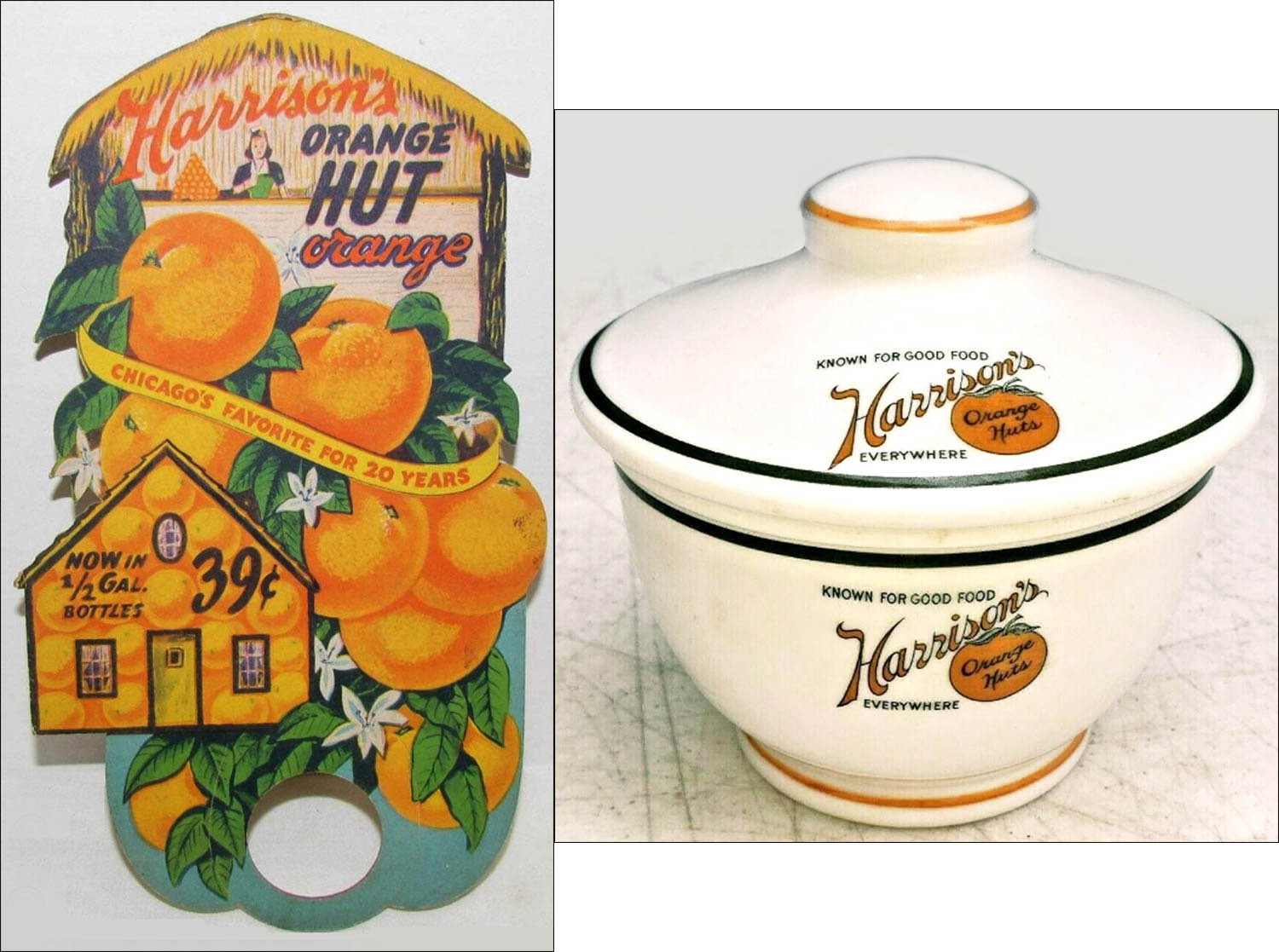

Harrison’s Orange Huts, a chain of fast-food stands selling orange drinks and five-cent hamburgers,15 occupied the storefront at 4804. The other shops facing Broadway were the Riviera Frock Shop at 4808 and Mrs. Brauer Birdie’s hat shop at 4810.

No entertainment venue was listed in the building—no Green Mill or anything with a similar name—suggesting that the big space behind the Photomaton was vacant at the time. (A Fanny May Candy Shop was at 4812 Broadway, the narrow structure sandwiched between the Green Mill building and the Uptown Theatre.)16

But on October 10, 1928, a new version of the Green Mill—formally called Ye Old Green Mill—welcomed crowds back into that space. “The cafe is furnished in Egyptian style, and has a private 250-seat banquet hall especially adapted for use by private parties and clubs,” the Northside Sunday Citizen reported. “… Miniature wooden mills will be given away at the opening. There will be broadcasting nightly over WIBO.”

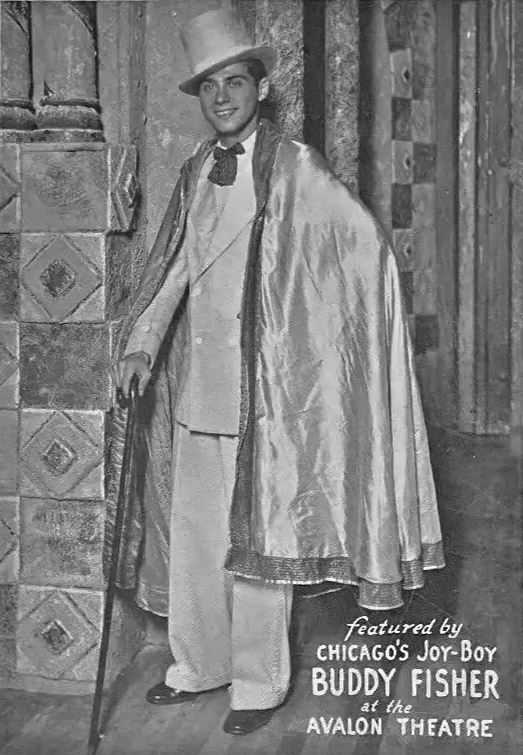

The opening attraction was The Green Mill Follies, produced by Billy Rankin and emceed by “Joy Boy” Buddy Fisher, who was once described as “a riotous ‘Nut’ comedian, a spontaneous and witty master of ceremonies … a favorite entertainer from Tin Pan Alley to Hollywood boulevard.”17

The follies show featured a chorus of 12 girls, and several “novelty entertainers”: the Nolan and Judith dancing team; Tiny and Leonard of George White’s Scandals; blues singer Lillian Barnes; prima donna Adele Walker, and soubrette Mary Stone.18

“Ye Old Green Mill steps into a new era with ‘Billy’ Rankin going along at a lively clip with his tuneful and gorgeously staged and gowned revue,” the Chicago Daily News noted in its “Where the Funseekers Go” column.19

The revived nightclub’s official name may have been Ye Old Green Mill, but the Chicagoan magazine’s Francis C. Coughlin simply called it “the Green Mill.” He visited the venue in December 1928, when he took a tour of the Wilson Avenue District’s supposed “hell holes,” as more prudish folks called Uptown’s entertainment venues.

As Coughlin observed, the neighborhood and its nightlife had a “salacious” reputation. But the Uptown that he saw during his nocturnal travels didn’t seem quite so racy. He offered this description of the area:

The night air is cold, Uptown. The blue air of the lake region, it is likely to be misty by day so that distant outlines are shaded and soft. But at night it is clear and cold so that electric lights are bogus jewels more detectably fraudulent than ordinary; and lighted sidewalks before store windows are merciless as a cheap photographer’s mercury light; they pick out young faces in sharp outline, making the skin green and the lips purple.

It is a region of cheap trinkets, quick lunches, shabby furs, jangling transportation and small apartments. A region not poor with the hopeless and tarnished poverty, of Madison street, say, or South Clark, and not vicious as South State in the 20-hundreds or North Clark from its 5 to 10-hundreds. But a poor district simply because its inhabitants are struggling, young, hopeful people, most of them new to the adventure of city living—clerks and stenographers and young salesmen and newly married folk, “Lil-and-Sandy” couples, to borrow a term from a magazine highly favored in Uptown.

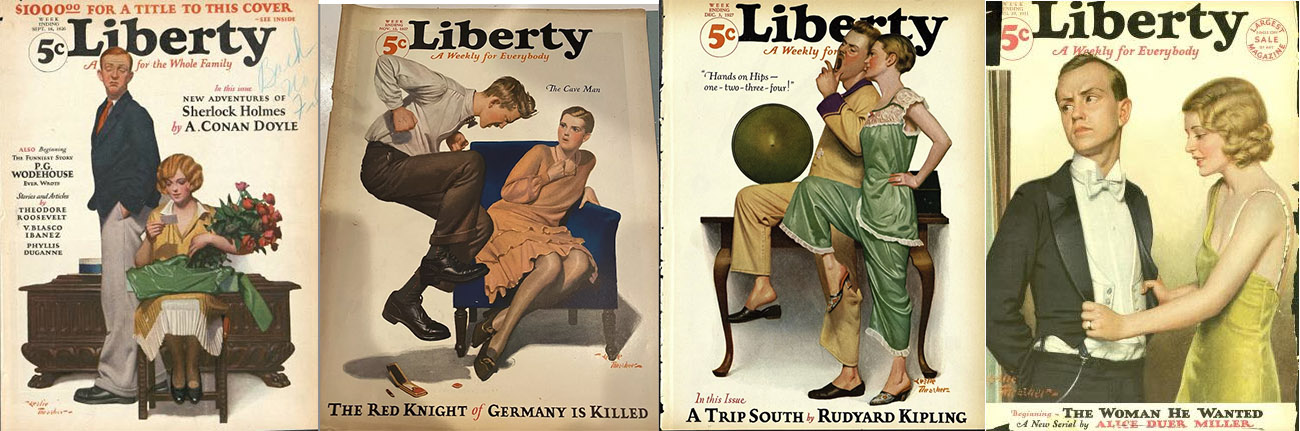

Coughlin was talking here about Liberty magazine, which featured artist Leslie Thrasher’s cover paintings chronicling the courtship and marriage of a middle-class couple, Lil Morse and Sandford Jenkins—a running story over six years, told entirely through pictures.20 This couple apparently exemplified Uptown’s residents.

Although Uptown was known as a place where people stayed out all night, Coughlin observed that things actually quieted down after 1 a.m.:

So it is that Wilson Avenue night life is cheap and joyous while it lasts, which is not much past 1 a.m. It is a night life of motion picture theatres, thrilling and gaudy and incredibly illuminated over the whole facade, and of public dance halls done in rococo splendor and in habited by a tribe of dancers whose steps are even more rococo and splendid than the hall architecture. Dine in a chop suey parlor, dance at the Aragon, and somehow part time payments on the dinner clothes get themselves paid. Of course a little drink is an added outlay, but it is none of the pretentious bottled stuff elaborately vended downtown; call the nearest drug store, delicatessen, barber shop, restaurant or shoe shine parlor and Joe, or Gus, or Emil dips your gin out of the bathtub. True it doesn’t come in a frosted bottle, but it is a downright specific against a blue and frosted nose, which is the main thing. Sing, oh sing, oh sing of Lydia Pinkham!

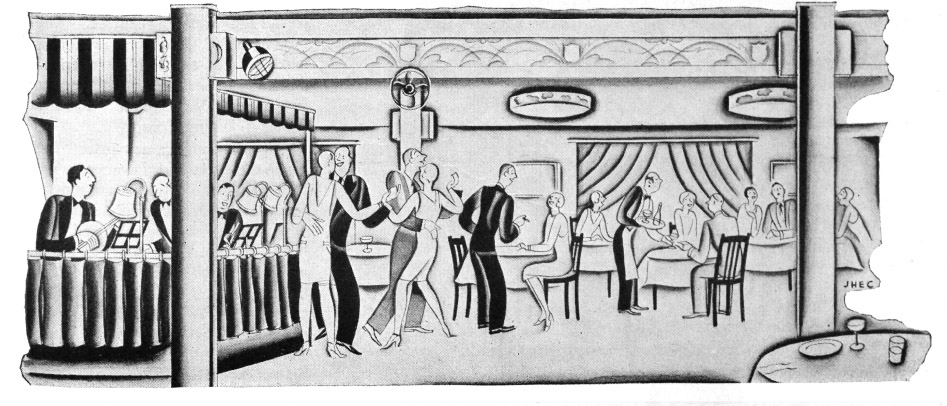

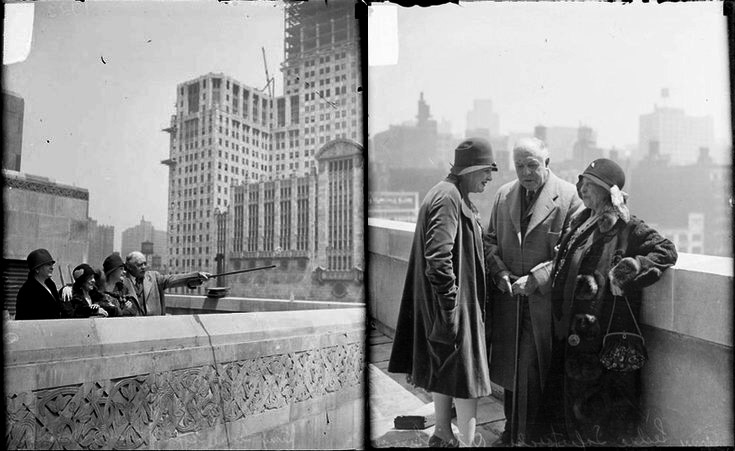

An illustration of an Uptown nightclub. Chicagoan, December 29, 1928.

And Coughlin gave this description of the Green Mill’s decor and vibe, noting that it had trouble competing with the elaborate shows happening a few doors away in Balaban & Katz’s Uptown Theatre:

And the best night place in the district, when movies have flickered out and dance halls closed, is the Green Mill.

A tall room done in the Aztec (or is it Inca?) manner with two guardian Indians on illuminated glass flanking the orchestra platform, a double stair down either side of the stage, ceiling and walls in red and yellow, a populous balcony on three sides, and brisk tables in military formation around the central dance floor—such is the Green Mill. A cross between dance hall and night club, and a rallying place for dancing couples who would rather dance than eat and—one would imagine to the chagrin of a club management—probably do.

Indeed, this urge to dance somewhat interferes with night club atmosphere. An entertainer is heard in a cabaret song, and the words are the traditional words sung the city over. Yet patrons do not yearn moistly across the ginger ale. Rather, they shuffle impatiently until Solly Wagner’s band moans into a dancing rhythm. They are off with glee. Even the floor show, which is elaborate as cabaret floor shows go and highly meritorious after its fashion, suffers in a kind of spiritual competition with the stage revues sponsored next door by the MM. Barney Balaban and Sam Katz. Capacity, even, looks toward the theatre. Full up, it is 785.

Yet an evening at the Mill goes pleasantly enough. It is not exciting. It is not rough. Unlike most cabarets, it is not notably soused. And among customers is a pleasant leaven of handsome young people at home in something approximating the true collegiate atmosphere, which is quiet and graceful and happy and poor. Such is a hell hole on Wilson Avenue. Dave Bondi is headwaiter.21

Ye Old Green Mill’s company president was Leonard (or Leopold) Leon, a 31-year-old Jewish immigrant from Ukraine,22 who’d previously owned Club Drexel.23 He also apparently worked as a bondsman, helping criminal defendants get out of jail.24 Leon owned only one $100 share of Ye Old Green Mill Inc., while his wife, Estelle Leon, owned $2,500. She was the company treasurer.

Their business partner, Leon Ignatius Sweitzer, was the majority owner, with shares worth $5,100.25 This 27-year-old World War I veteran26 was a first cousin27 of Cook County clerk Robert M. Sweitzer,28 a Democrat who’d lost the 1915 and 1919 mayoral elections to Republican Big Bill Thompson.29 The Citizen described Leon Sweitzer as a “well-known cafe man,”30 but he was also employed as a Chicago police detective—until he was fired the following February, when the Chicago Police Department’s trial board found him guilty of “disobedience.” At the time, he was also reportedly facing a federal criminal charge.31

Tribune reporter James Doherty later called Sweitzer and Leon “front men” for North Side gangster Ted Newberry. Doherty was “sure” that Newberry was the Green Mill’s real owner at this time.32

On January 18, 1929, Joe Lewis returned to the perform at the Green Mill, headlining at the club he’d famously departed a year and a half earlier.33 According to Art Coen’s book The Joker Is Wild, the venue’s new owners decided that the best man to “resuscitate it was the one who had left it to die.” And so, they asked Lewis if he’d come back for $1,000 a week plus a cut of cover charges and a contract allowing him to remain as long as he wanted. He said yes.34

A week later, the Daily News offered praise for the entertainer, who was making a comeback following the attack that had almost killed him: “Joe Lewis, the comedian, seems to be better than ever and keeps ‘packing them in’ every night at the Green Mill.”35

But Coen’s book, which was based largely on interviews with Lewis, paints a less flattering picture of the entertainer’s return stint at the Green Mill: “He was not as pitiful as he had been the year before but his brain and his speech still were not coordinated: he lacked the essential timing that makes the difference between a star and a tenth-rater. The Green Mill did some business but neither it nor Joe could recapture their popularity of 1927. Customers were drawn out of curiosity or pity and few came back.”36

And yet, the Chicagoan’s “Current Entertainment” column often described the Green Mill in glowing terms in 1929: “A later purveyor to the wakeful in the Wilson Avenue district, the Mill boasts Solly Wagner’s band, a slick dance floor, entertainers, a lavish revue and satisfied customers.”37 … “Largest of northside night clubs, the Green Mill is lavish, tuneful and well attended.”38 … “A lingering jewel in the crown of north side night life.”39

According to The Joker Is Wild, two thugs in Bugs Moran’s North Side gang, Pete and Frank Gusenberg—brothers who’d served as Lewis’s bodyguards when he was lying in the hospital—stopped into the Green Mill a little after 4 a.m. on February 14, 1929, to hang out with Lewis. One of the Green Mill’s owners was frightened of these hoodlums, telling Lewis, “You know how they get when they’re plastered.” As the morning went on, their inebriated joking turned into tense arguments. Frank Gusenberg pointed at the owner, telling Lewis: “There’s one sonofabitch I don’t like. … He’s a chinchy sonofabitch and I hate his guts.” This encounter supposedly happened—if you can believe the story in Coen’s book—several hours before the Gusenberg brothers were killed in the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.40

In late February, a “battle royal” erupted one night as 25 couples were dancing in the Green Mill. “All of a sudden bottles started to fly,” the Tribune reported. “Glasses were next. Chairs and tables were overturned as the guests sought exits. A singing waiter cut short his song when a bottle rolled off his head.” A patron named Cliff E. Clark said a gunshot hit his thumb as he was running for an exit. “He was unable to explain how the trouble started,” the Tribune noted. “When the police arrived the café was under lock and key.” It’s not clear if the police ever came up with an explanation for what this melee was all about.41

In March 1929, the newly elected president of the United States, Herbert Hoover, received a delegation of Chicago’s civic leaders. He was shocked by their description of life in Chicago. Hoover learned “that Chicago was in the hands of gangsters,” he later wrote, “that the police and magistrates were completely under their control, that the governor of the state was futile, that the federal government was the only force by which the city’s ability to govern itself could be restored. At once I directed that all the Federal agencies concentrate on Mr. Capone and his allies.”42

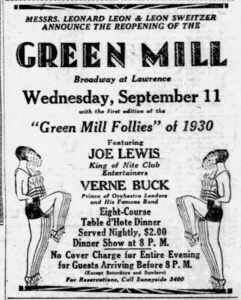

On June 22, 1929, the Chicagoan reported, without explanation, that the Green Mill would be “closing any day now.”43 The venue apparently shut down for some reason, but a few months later, Leonard Leon and Leon Sweitzer announced that they were reopening it on September 11, with a new version of Green Mill Follies featuring Joe Lewis, “King of Nite Club Entertainers,” and Verne Buck, “Prince of Orchestra Leaders.”44

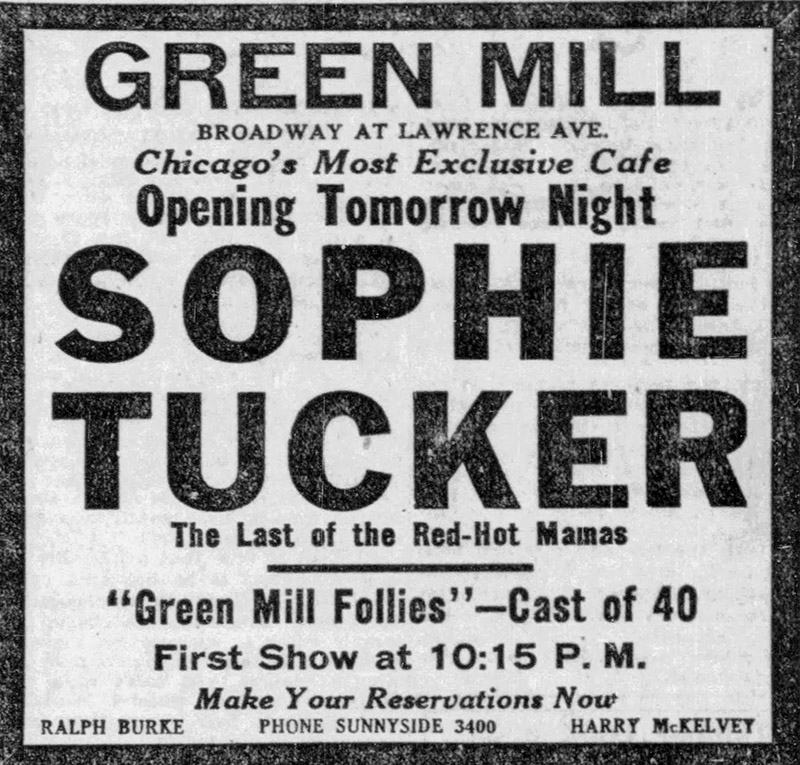

Lewis was gone by the end of October, when one of the era’s biggest stars, Sophie Tucker, opened her show on Halloween night, beginning a four-week run at the Green Mill. (As it happened, Tucker’s opening night was just three days after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 ushered in the Great Depression.)

The Green Mill’s ads hyped Tucker as “The Last of the Red-Hot Mamas,”45 a nickname taken from a hit record she’d released that summer.46

In the chorus, she sang:

’Cause I’m the last of the red hot mammas

They’ve all cooled down but me!

Flapper vamps, say, what do they know?

Come get your hot stuff from this volcano

I’m an overheated, try and beat it

Hotsy-totsy Hottentot

Now, it may be snowing

But when I get going

Oh, baby, I’m hot!47

A Jewish immigrant from Ukraine, Tucker was famous for her brassy voice and her equally strong personality.48 She’d recorded one of her signature tunes in 1911, after a Black musician in Chicago named Shelton Brooks suggested she should sing his composition, “Some of These Days.” A new recording of that song became a No. 1 hit in 1926, selling more than a million copies.49 (Brooks was one of the few African Americans who performed at Green Mill Gardens, appearing at the venue in 1920.50)

Tucker had other connections to Chicago, including her marriage to bandleader Frank Westphal, which lasted from 1917 until 1920; after they divorced, he led the orchestra at Rainbo Gardens.51 When Tucker performed at the Green Mill in 1929, she was 42 years old. Her first movie, Honky Tonk, had come out that August.52

Decades later, Chicago Sun-Times columnist Herb Graffis would reminisce about seeing Tucker at the Green Mill. “She never needed a microphone, our Sophie,” he wrote. “She would blast out a song so she rattled the plates and the folks in Sioux City could hear a few bars free.”53

Daily News critic Amy Leslie reported that Tucker was “simply tearing the air wide open with splendid ragtime” at the Green Mill, performing with “a tribe of pretty women,” numbering 40. Leslie offered this review of Tucker’s show:

Sophie Tucker came like a cyclone in the wake of the lake storm and planted her jazz banner where it would wave the loudest at the delightful Green Mill, where good entertainment is always found and expected. Nobody is so welcome as the buxom and richly gifted, original and popular Sophie. She has the best songs ragtime and jazz has ever given us and she regards them all of the “red-hot mama” variety, though they are not, and her little girl assistants are modest, cheery, industrious and dressed like burlesque queens on parade.

Miss Tucker’s voice is a splendid organ, well trained and inviting applause. She broke out Thursday in the middle of a Halloween celebration, the biggest pumpkin lit up for the occasion of prank and caper, in rowdy noise and all the jazz of mind and soul possible to the world of fun.

The Green Mill Gardens made a note of the event and it will go down in history as one of the great, big things the Garden ever gave its customers.54

In the middle of Tucker’s monthlong run at the Green Mill, Chicago’s WBBM radio station began live broadcasts of her shows at the nightclub, at 11 p.m. every Tuesday and Thursday.

“Twice a week, Miss Tucker will face the microphone of the Chicago station in the Green Mill cafe, and put on a program for the radio audience,” the Rockford Daily Register-Gazette, noting that WBBM’s signal could reach listeners as far away as the East Coat and West Coast. “She has chosen WBBM as the medium because of its national coverage through its new high powered transmitter and because of its central location in Chicago which she is preparing for her European tour,” the newspaper said. 55 The Chicago Daily Times offered this data about the station’s signal and where people could find it on their radios: “Frequency 770 kilocycles. Wavelength 389.4 meters—Power 25,000 watts.”

The Times also noted that Tucker had borrowed Chicago mayor Big Bill Thompson’s slogan, “America First.” She was using the motto to describe some of the songs she sang on the radio: “Miss Tucker is preparing for an European tour by adding several new songs to her repertoire. Instead of waiting to let the people of the United States hear them after her return, she is including them on her radio programs that they might be heard by listeners throughout the land.” WBBM’s “Air Theater” also featured performances by Verne Buck’s Green Mill orchestra.56

Meanwhile, a court case in December 1929 offered a glimpse at the expectations for the “pretty women” and “little girl assistants” who danced on the Green Mill’s stage. A judge ordered Ye Old Green Mill to pay $110 to one of its dancers, Dolores Weeks, 21, of 1300 West Argyle Avenue. It’s not clear whether Weeks was part of Sophie Tucker’s show, though the timing of her litigation suggests that this might be the case.

Weeks said she’d been hired to do a “specialty” dance for four weeks, but the nightclub had fired her after the end of her third week. As the Daily Times explained, “Dolores wouldn’t go out on champagne parties with the big butter and egg men who had come to Ye Green Mill spot to inspect ye chickens.” The judge ruled in her favor. The Times headline summed up the judicial findings as follows: “Green Mill Must Pay Dancer ‘Even If She Doesn’t Flirt.’”57

In December, the Chicago Daily Times reported that another sassy, boisterous female star was taking over the Green Mill. The nightclub hostess Texas Guinan had been attracting big crowds in New York City—and making headlines when federal authorities failed to convict her of alleged prohibition crimes. “Texas says she bought the Green Mill to show Chicagoans that a night club is not the dark and mysterious place it is cracked up to be, but a place of loud music, girls and bright lights, where any man without a wife can be safe,” the Times wrote.

The newspaper reported that Texas Guinan would “take command” of the Green Mill in late December.58

PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER

Footnotes

1 “Green Mill Closed,” Variety, December 14, 1927, 55, https://archive.org/details/variety89-1927-12/page/n117/mode/2up.

2 “Green Mill Reopens,” Variety, February 1, 1928, 57, https://archive.org/details/variety90-1928-02/page/n55/; “Burke Reopens Green Mill,” Uptown Citizen, January 27, 1928, 1.

3 “Dry Agents Mop Up Beer Near Ward Picnic,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 17, 1928, 8.

4 Green Mill Gardens Inc. (1928) corporation papers, Secretary of State (Corporations Division): Dissolved Domestic Corporation Charters, 103/112, Illinois State Archives, Springfield.

5 1920 U.S. Census, Illinois, Cook, Cicero, enumeration district 0054, sheet 5B; 1930 U.S. Census, Illinois, Cook, Chicago (Districts 251-500), enumeration district 0263, sheet 13A; Maureen Barnett-Betz, Barnett – Cutting / Werle Family Tree, accessed January 13, 2024, Ancestry.com.

6 “Cabaret Manager Robbed of $2,100, Night’s Receipts,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 11, 1927, 17.

7 “Dave Peyton,” Wikipedia, accessed February 1, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dave_Peyton.

8 Dave Peyton, “The Musical Bunch,” Chicago Defender, January 21, 1928, 6; February 18, 1928, 6.

9 Document 10828437, book 28686, page 21, Tom Chamales et al, Agreement, filed January 16, 1931, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

10 “Shelley v. Kraemer (1948),” Legal Information Institute, updated April 2021, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/shelley_v_kraemer_(1948).

11 “Quarter-in-Slot Photo Studio for Broadway,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 29, 1928, part 3, 3.

12 “Anatol Josepho,” Wikipedia, accessed July 16, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anatol_Josepho#The_Photomaton; “Slot Photo Device Brings $1,000,000 to Young Inventor,” New York Times, March 28, 1927, 1, 10, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1927/03/28/97228521.html?pageNumber=1.

13 Chicago Tribune photo, circa 1928, @vintagetribune, November 30, 2023, https://www.instagram.com/p/C0P4eyptz5M/.

14 1930 U.S. Census, Illinois, Cook, Chicago (Districts 2877-2908), District 2887, 4B, Ancestry.com.

15 Ed Phillips, “Harrison’s Orange Huts,” Restaurant Ware Collectors Network, January 22, 2023, https://rwcn-idwiki-2.restaurantwarecollectors.com/content/harrisons-orange-huts/.

16 Polk’s Chicago (Illinois) Numerical Street and Avenue Directory, 1928–1929 (Chicago: R.L. Polk & Co., 1928), 93, http://chsmedia.org/househistory/polk/menus/polkb.pdf.

17 “Comic Leader and Band to Return Here,” (Shreveport, LA) Times, February 18, 1934, 24.

18 “Green Mill Reopens 10th,” Northside Sunday Citizen, October 5, 1928, 1.

19 “Where the Funseekers Go,” Chicago Daily News, November 10, 1928, 9.

20 Joyce K. Schiller, “I’m Dying, Egypt, Dyin,” Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, June 19, 2009, https://rockwellcenter.org/essays-illustration/june-19-2009/.

21 Francis C. Coughlin, “Adventures in Insomnia,” Chicagoan, December 29, 1928, 11. http://chicagoan.lib.uchicago.edu/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/mvol-0010-v006-i07/mvol-0010-v006-i07.xml#page/13/mode/1up.

22 1930 U.S. Census, Illinois, Cook, Chicago (Districts 1251-1500), District 1421, 20A; Illinois, U.S., Federal Naturalization Records, 1856-1991; U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918; Howard2855, Bernard Coleman Chicago Family Tree; Clare Narrod, Narrod/Naroditsky/etc. Family Tree, accessed February 4, 2024, Ancestry.com.

23 “Green Mill Reopens 10th,” Northside Sunday Citizen, October 5, 1928, 1.

24 “Cafe Free for All Remains a Mystery to All Concerned,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 27, 1929.

25 Ye Old Green Mill Inc. corporation papers, Secretary of State (Corporations Division): Dissolved Domestic Corporation Charters, 103/112, Illinois State Archives, Springfield.

26 Wilson-Copp Family Tree, accessed February 4, 2024, Ancestry.com.

27 Betsko Family Tree, accessed February 4, 2024, Ancestry.com.

28 “Sweitzer, Ex-County Official, Dies,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 7, 1938, 1.

29 “Chicago Mayors, 1837-2007,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1443.html.

30 “Green Mill Reopens 10th,” Northside Sunday Citizen, October 5, 1928, 1.

31 “Detective, Owner of Green Mill, Is Fired,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 2, 1929.

32 James Doherty, “Texas Guinan, Queen of Whoopee!” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 4, 1951, Grafic Magazine, 4–5.

33 “Where the Funseekers Go,” Chicago Daily News, January 12, 1929, 21.

34 Art Cohn, The Joker Is Wild: The Story of Joe E. Lewis (New York: Random House, 1955; New York: Bantam, 1957), 57.

35 “Where the Funseekers Go,” Chicago Daily News, January 26, 1929, 11.

36 Cohn, Joker Is Wild, 57.

37 “Current Entertainment,” Chicagoan, February 9, 1929, 4. http://chicagoan.lib.uchicago.edu/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/mvol-0010-v006-i10/mvol-0010-v006-i10.xml#page/6/mode/1up.

38 “Current Entertainment,” Chicagoan, April 27, 1929, 4. http://chicagoan.lib.uchicago.edu/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/mvol-0010-v007-i03/mvol-0010-v007-i03.xml#page/6/mode/1up.

39 “Current Entertainment,” Chicagoan, June 22, 1929, 4. http://chicagoan.lib.uchicago.edu/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/mvol-0010-v007-i07/mvol-0010-v007-i07.xml#page/6/mode/1up.

40 Cohn, Joker Is Wild, 57–61.

41 “Cafe Free for All Remains a Mystery to All Concerned,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 27, 1929.

42 Daniel Okrent, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (New York: Scribner, 2010), 344–345. Cited source: Herbert Hoover, The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover: The Cabinet and the Presidency, 1920–1933 (New York Macmillan, 1952), 276–277.

43 “Current Entertainment,” Chicagoan, June 22, 1929, 4. http://chicagoan.lib.uchicago.edu/xtf/view?docId=bookreader/mvol-0010-v007-i07/mvol-0010-v007-i07.xml#page/6/mode/1up.

44 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, September 9, 1929, 35.

45 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, October 30, 1929, 31; “Chicago,” Variety, December 4, 1989, 61, https://archive.org/details/variety97-1929-12/page/n59/.

46 “Sophie Tucker,” Discography of American Historical Recordings, accessed July 16, 2024, https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/105584/Tucker_Sophie.

47 Milton Ager (music) and Jack Yellen (lyrics), “I’m the Last of the Red Hot Mammas,” Genius, accessed July 16, 2024, https://genius.com/Sophie-tucker-im-the-last-of-the-red-hot-mammas-lyrics.

48 “Sophie Tucker,” Wikipedia, accessed July 16, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sophie_Tucker.

49 “Sophie Tucker: ‘The Pride of Hartford,’” Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford, accessed July 16, 2024, https://jhsgh.org/omeka-s/s/sophie-tucker/page/if-you-could-sing.

50 “With the Actors,” Chicago Whip, July 17, 1920, 3. https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=TCW19200717-01.1.3&srpos=51&e=——-en-20–41-byDA-img-txIN-%22green+mill+gardens%22———.

51 “Frank Westphal,” Wikipedia, accessed July 16, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Westphal.

52 “Honky Tonk (1929 Film),” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Honky_Tonk_(1929_film); advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, August 26, 1929, 34.

53 Herb Graffis, “A Young Man’s Fancy When Chicago Was in Bloom,” Chicago Sun-Times, Midwest Magazine, November 18, 1973, p. 49.

54 Amy Leslie, “Stars Entertain in the Gardens and Night Clubs,” Chicago Daily News, November 1, 1929, 17.

55 “Sophie Tucker Broadcasts at Station WBBM,” (Rockford, IL) Daily Register-Gazette, November 16, 1929, 4

56 “Radio Programs,” (Chicago) Daily Times, November 26, 1929, 24.

57 “Green Mill Must Pay Dancer ‘Even If She Doesn’t Flirt,’” (Chicago) Daily Times, December 18, 1929, 8.

58 “Come On Suckers! Guinan Buys Club,” (Chicago) Daily Times, December 12, 1929, 43.