CHAPTER 23 of THE COOLEST SPOT IN CHICAGO:

A HISTORY OF GREEN MILL GARDENS AND THE BEGINNINGS OF UPTOWN

PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER

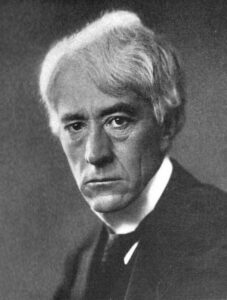

As prohibition became the law of the land in 1920, many Chicagoans kept on drinking. “Chicago is as wet as it ever was,” the region’s chief prohibition officer, Alfred V. Dalrymple, said that summer, bemoaning the fact that he didn’t have enough men to “investigate all the complaints that come in from a city of 3 million.”1

Everyone called him “Major” Dalrymple, using the rank he’d attained during his military service. He’d fought in the Spanish-American War before leading a five-year campaign against narcotics in the Philippines.2 Now, Dalrymple was engaged in another war.

He made headlines in February 1920, when he led 35 federal agents from Chicago to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, where the Iron County state’s attorney refused to enforce prohibition. Dalrymple called that “an actual revolt against the United States government.” Dalrymple and his men—armed with submachine guns and revolvers—confiscated wine from the basement of a priest’s house, smashing the barrels and pouring 450 gallons into the street. The major also posed for newsreel cameras, alongside the rebellious but now pacified local prosecutor.3

Dalrymple did not find it so easy to vanquish Chicago’s purveyors of booze. The city’s newspapers kept on writing about a mysterious “$1 million whisky ring” that was surreptitiously bringing liquor into the city and delivering it to cabarets, cafés, and private homes. Dalrymple and other officials vowed to expose high-ranking politicians who were supposedly involved in the ring.

One truck driver confessed that he’d delivered 700 of cases of alcohol, picking it up at a South Side furniture warehouse and taking it to the homes of “leading Chicagoans” and wealthy families in the Gold Coast and the “North Shore.” (In that era, “North Shore” often described the area around Uptown, Edgewater, and Rogers Park.)4

Joe Spagat, an Edgewater Beach Hotel employee who’d previously worked as a manager at Green Mill Gardens,5 was accused of arranging whiskey deliveries to the house of Charles B. Smith, the millionaire president of the Stewart-Warner speedometer company. “Spagat was a go-between—arranging for the transportation of the booze from the warehouse,” Dalrymple said.6

More than $1 million worth of liquor was supposedly stolen in hundreds of robberies, including truck heists, during the first eight months of prohibition. In many cases, this was alcohol that had been purchased for personal use back when it was still legal. Such alcohol couldn’t be transported without special permission from the government. Authorities suspected these “robberies” were shams.7

And they suspected that Chicago cops were assisting in these robberies—or shaking down bootleggers. “I have received an average of four complaints a day about men supposed to be policemen, detectives, internal revenue officers, or men from my own office, who have tried to shake down the bootleggers,” Dalrymple said.8

Early one morning in May, a North Sider named Fred Wolf was driving his 10-ton red truck on South Halsted Street, carrying $25,000 to $30,000 worth of bottled liquor covered by a tarpaulin. Straw was stuffed between the bottles to muffle their clinking. The intended destination for this booze was Rainbo Gardens, the popular nightclub at Clark Street and Lawrence Avenue.

Four police officers approached the truck near 21st Street, drawing their revolvers and showing their stars. After getting into truck, they soon told Wolf and his assistant to get out. “Beat it away from here quick, and if you ever identify us, you’ll get yours,” they reportedly said.

Wolf telephoned Fred Mann, the owner of Rainbo Gardens, who talked quietly with some police officials he knew. They set up a meeting where Wolf could look over the Maxwell Street police station’s officers. He identified two of them as the robbers.

The truck was empty when it was found. This was the second time in five months that a truck was hijacked while attempting to deliver liquor to Rainbo Gardens. Mann threatened to bring accusations about the officers in front of the police department’s disciplinary board if he didn’t get his liquor. “I am prepared to go to the City Hall and fight the case to a finish, whatever the cost may be to me,” he said.9 (Curiously, Mann seemed less concerned that he might face criminal charges of his own for transporting and selling alcohol.)

The criminal case against the cops quickly fell apart, when the truck driver said he’d been mistaken when he identified them.10

“No police are involved in the moving of liquor in Chicago,” police superintendent John J. Garrity insisted.11 But as the year went on, Garrity charged a few of his officers with soliciting bribes from saloonkeepers.12

A federal prosecutor told reporters: “The Chicago police department is honeycombed with booze graft.”13

One police captain suggested that the department faced an impossible task. “How the devil is a policeman going to stop the sale of booze?” he said.14

Just who was leading the conspiracy behind the “whisky ring”? The feds said the mastermind—or at least one mastermind—was Michael Heitler, a notorious West Sider nicknamed “Mike De Pike,” who’d served prison time for operating brothels.

Now, Mike De Pike was allegedly running Chicago’s “booze board of trade.”15

In the fall of 1920, Heitler was arrested with 31 other men,16 including distillers, saloonkeepers, railroad detectives, and five police officers.

They’d allegedly used a Rock Island Railroad train to transport 1,000 cases containing 3,000 gallons of whiskey from the Old Grand-Dad Distillery in Kentucky to Chicago’s Gresham Station. Cops were accused of taking bribes and allowing the booze to be unloaded.

After saloonkeepers picked up their orders and drove off, their trucks were hijacked—and one truck driver identified the robbers as Chicago police officers.

A Jass Interlude

By the time this case went to trial in 1921, everyone in America must have known the meaning of the word jazz. But another version of that word surfaced during the testimony. Maurice “Mossy” Joy, one of the people who’d allegedly been ripped off by the “whisky ring,” had angrily exclaimed, “Jass them.”

That prompted a lawyer to ask witness Albert Greenwald: “What did you understand him to mean by ‘jass’?”

Greenwald answered: “Well, anybody who knows how to talk slang knows what that means.”

The judge interjected, “Court and counsel don’t know.”

This line of questioning ended there, without any further explanation. But this exchange suggests that jass had a vulgar meaning in the lingo used by criminals, a definition similar to fuck or screw.17

Clarence Darrow represented one of Heitler’s codefendants, a railroad worker and World War I veteran named William Gorman. “The government tells us that anarchy and bolshevism will follow the uncurbed violation of this law,” Darrow told the jury. “I want to say that my client was fighting for his country while the fanatics were making this law.”18

In the end, Heitler was one of only five men found guilty in the case, getting a prison sentence of two years. The promises by authorities to expose high-level corruption didn’t amount to much in this case: Not a single police officer was convicted. (Darrow’s client was also acquitted.)19

Heitler was allied with mobster Johnny Torrio and his gang, which included Al Capone,20 but it’s not clear if Torrio’s gang assisted Heitler with this whiskey operation. Years later, after Heitler got out of prison, the Capone mob allegedly killed him when he was said to be talking with the state’s attorney’s office. Mike De Pike’s body was found in the charred ruins of an ice house that burned down near Barrington in 1931.21

While authorities were trying to crack open the “whisky ring,” Dalrymple warned about another source of liquor: doctors and druggists. Federal prohibition law allowed pharmacists to sell a limited amount of liquor to customers who had a doctor’s prescription for it.22

“There is an extremely large percentage of unscrupulous doctors in Chicago who are prescribing liquor at wholesale without examining their patients,” Dalrymple complained. “Too large a percentage of druggists are in cahoots with these doctors. Some of them are trying to debase my men, but I have the goods on ’em. … I have found some physicians in Chicago who are filling out 500 whiskey prescriptions a day.”

The state’s prohibition director set new limits: Illinois druggists could sell no more than 100 gallons of whisky, wine, gin, or other proof liquor a month.23

“I am not in favor of drug stores being converted into saloons!” John J. Boehm, a South Side druggist who was also a state senator, exclaimed at an Illinois Pharmaceutical Association meeting. “That is what you’re trying to make of them. It is rumored that one druggist in my neighborhood has recently made $60,000 through illegal liquor sales. There are scores of druggists doing the same thing.”

But another Chicago pharmacist, George Haering, responded: “Whisky and alcohol are no longer poisons. They are now medicines, and druggists have a right to sell them.”24

As it happened, a drugstore had opened in 1920 at the northwest corner of Lawrence Avenue and Broadway—taking over a space that had been a saloon within the Green Mill Gardens complex. There don’t seem to be any reports about suspicious liquor sales at this drugstore, but it may well have been at least a limited source for alcohol.

It was called Riviera Drug Company, echoing the name of the movie theater across the street. It appeared in Chicago phone books for the first time in June 1920, listed at 4800 Broadway. The store also used 4802 as its address when it placed classified ads, seeking to hire a clerk, a “soda man,” and an experienced girl to wait on tables.25

Over the following 13 years, a drugstore would continue operating at that corner. The drugstore is visible in photographs, listed in telephone books, property records, and court cases, and mentioned in various newspaper advertisements and articles. When druggist William C. Weihe26 purchased the business and took over the lease at 4800 Broadway in 1923, he took out a $35,000 chattel mortgage on the store’s furnishings. That document offers a glimpse of the store’s interior, listing its contents:

There were 13 stools along the store’s counter, which had a double soda fountain. There was one showcase next to a window on the south wall, which looked out onto Lawrence Avenue. The north wall had a case that was 33 feet long. Elsewhere, the space contained a 40-foot-long wall case, four 10-foot showcases, two 30-foot prescription cases, and one case for candy—and six telephone booths. The other odds and ends included two National cash registers, one electric sign, drug utensils, silverware, and crockery.27

There were moments of both sorrow and joy at Green Mill Gardens in 1920.

Content warning: The next paragraph discusses suicide. If you or someone you know is suicidal, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988.

Tragedy struck at the end of April, when the cabaret’s performers included a recently divorced cabaret singer named Marie Williams. After the show, she went to her home on nearby Magnolia Avenue. Two days later, a passerby noticed an odor of gas outside her place. He called the police, who forced her door open. They found six burners wide open on her gas stove. Williams had been dead for several hours. She’d written a message with a stick of lip rouge on the mirror of her dressing table: “Have no pencil. Tell mother I am at ease.”28

A happier occasion took place in July, when two of Green Mill Gardens’ best-known dancers, Mlle. Marion and Martinez Randall, got married at the venue. Chamales extended invitations to many of Chicago’s entertainers.29

And on November 25, Chamales got married himself—to Helene D. Von Keilbach. He was 42 or 43 years old at the time, and she was 20. Her father, Theodore, was a saloonkeeper whose parents were both German immigrants. Her mother, Alice, was a child of Irish immigrants. Helene had grown up on Chicago’s South Side, but after she married Tom Chamales, they lived in north suburban Wilmette.30

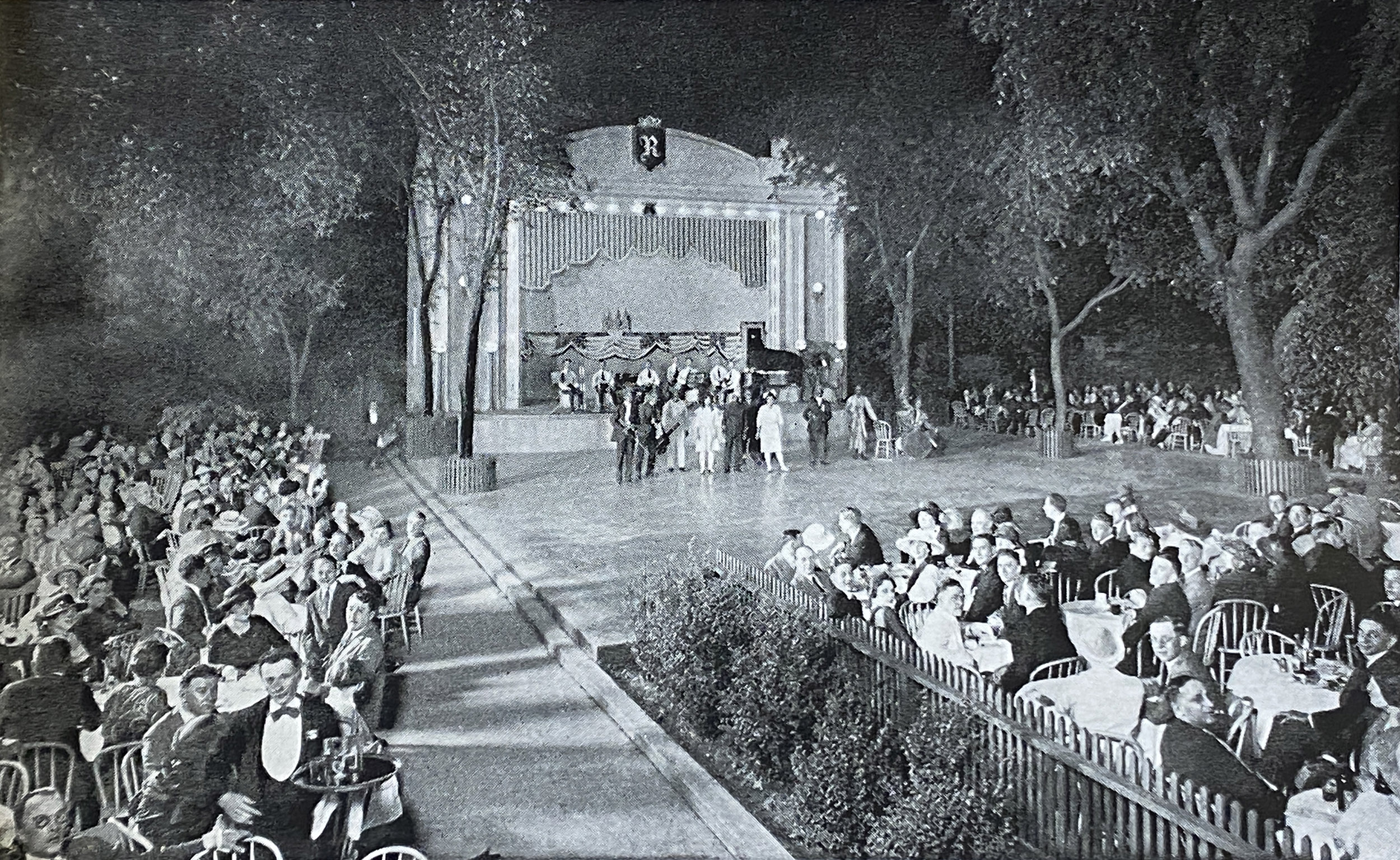

Joe Frisco was the star attraction when Green Mill Gardens opened its 1920 outdoor season on June 25.31 Frisco, a stuttering comic renowned as the originator of jazz dance, performed with his longtime partner Loretta McDermott, 32 and the New York Clipper reported “an audience that filled every vacant space available.” Hundreds of entertainers were in the crowd.

“Frisco jazz danced in his same old manner,” the Clipper commented. “… Miss McDermott proved a lively morsel of feminine cleverness and proved an exceptionally clever dancing mate to her eccentric partner. In conjunction with Frisco were seen the Royal Italian Quintette, an aggregation of instrumentalists, who seemed to win over the greater portion of the audience with their technic and showmanship. Coletta Ryan sang in a beautiful cultivated voice and also registered distinctly. Al Wohlman proved a laugh getter with his comedy numbers and gained popularity exceedingly early during his turn.”33

In spite of this positive review, the Clipper later reported that “Frisco and Loretta McDermott failed to cause any great excitement during their engagement at the Green Mill Gardens.”34

Paul Biese’s group—described as a “Saxophone Jazz Band”35 and a “syncopated jazz orchestra”36—started headlining at Green Mill Gardens in mid-July and continued playing for at least a month.37 Biese (whose real name was Percy Hawthorne Sudborough) was famous for his “moaning saxophone.” He was one of the first white bandleaders to feature the tenor saxophone prominently in popular music. He made more than a dozen recordings in 1920, including songs such as “Chili Bean,” “That Moaning Melody,” “Idol Eyes,” “Sweet Sugar Babe,” “Timbuctoo,” and “Happy Hottentot.”

Biese was also known for his weight. He reportedly weighed as much as 400 pounds at one time. Four months before starting his gig at Green Mill Gardens, Biese had made news when one of Chicago’s best-known physicians, Max Thorek, performed an operation on the saxophonist, removing 100 pounds of skin and fat from his abdomen.

“It will be impossible for the excess fat to return,” Thorek predicted. “With its removal the skin was cut away and tightened so that fat cannot longer grow about the girth.” Described as “one of the most unusual surgical operations on record,” the operation seemed to be a success, at least according to newspaper reports at the time.38 But five years later, it was blamed for Biese’s death from a stroke. He died at the age of 40.39

On July 17, Superintendent Garrity filed complaints against three cabaret proprietors for staying open after 1 a.m.: Green Mill Gardens owner Tom Chamales; Fred Mann of Rainbo Garden; and Charles Ritty, the manager of Ike Bloom’s Midnight Frolic, 20 East 22nd Street.40

The Green Mill and several other venues reportedly agreed to close at 1 a.m., but Ike Bloom refused, vowing to challenge the constitutionality of the city’s cabaret ordinance. “Bloom’s place does not get a start until after 1 a.m., and he is the greatest sufferer, due to the fact that he has just produced a new frolic, containing nearly thirty people,” the New York Clipper reported, referring to the cabaret’s “frolic” shows. “… Bloom has absolutely refused to close his place and the police … report that he is going at full blast.”

On August 9, it looked like Rainbo Garden was going to have a busy night. The Tribune offered this colorful description of the scene: “‘O, by gosh, by gee, by gum, by jingo’ vamped the jazz band. The evening’s business was picking up. Motor after motor drove up to the door. The tables were well filled.”

According to the Tribune’s report, a prohibition investigator was sitting at a table in the café when five men walked in shortly after 8 p.m. But this investigator was unaware that those men were also prohibition agents. He motioned for a waiter and ordered a rye highball. When the waiter returned with the cocktail and set it down on the table, one of the other men came over and reached for it. Asked what he was doing, the cocktail grabber said, “I’m from Dalrymple’s office.”

“So am I,” said the investigator who’d ordered the highball. He watched as the five other prohibition agents raided the nightclub. The Tribune described what happened next: “The women begged the raiders to leave the liquor behind. A number of youths talked of taking the stuff by force. Others grumbled. The ‘sub debs’ tilted their powdered noses. Raiders are such a bother.” (“Sub deb” was slang for a girl who will soon come out as a debutante—hence, a girl in her midteens.41)

The federal agents took Rainbo owner Fred Mann and his son, Alexander, into custody and confiscated 75 gallons of whisky, wine, and Champagne. The Tribune called it “one of the most successful raids in the history of Maj. A.V. Dalrymple’s office.”

The agents weren’t done for the night, however. They quickly headed over to Marigold Garden and Green Mill Gardens. But when they arrived at those venues, there was no liquor to be found.

The Tribune suggested that the “underground telegraphy” had moved faster than the prohibition agents. In other words, someone at Rainbo tipped off the Green Mill and the Marigold to hide their booze. Of course, it’s also possible that those places didn’t have any liquor to be raided on this particular night—or just did a better job of concealing it.42

On October 9, federal agents for the internal revenue collector again raided some of Chicago’s saloons and cabarets, including Green Mill Gardens and Rainbo Garden, taking samples of beer.43

In November, there was a changing of the guard in the war against Chicago booze. Dalrymple quit his job as the region’s prohibition director.44 As he was on his way out, federal prosecutors seemed to redouble their efforts to get tough on places selling alcohol. They called up cabaret proprietors, ordering them to remove all alcohol from their premises.

“This is a warning from the district attorney’s office that you’d better follow,” assistant U.S. attorney John J. Kelly said. “Get all booze out of your place before 6 o’clock tonight. Keep it out. Don’t let guests pour their liquor. Don’t let your waiters sell liquor to guests. If you try to beat this, you’re not going to get away with it. We’re going to watch you and you can expect a raid any time. If we find you have not obeyed this order, we’re going to file an injunction against your place and have it closed as a nuisance, besides seeing that you get the limit in the federal court if possible. That’s all.”

Up until this time, saloon owners and cabaret proprietors had avoided prosecution by arguing that they couldn’t be held responsible for patrons bringing their own alcohol into these establishments. Now, U.S. attorney Charles F. Clyne was threatening to prosecute these places for allowing “hip” liquor.45

Agents from virtually every investigative agency in the U.S. government joined together November 6 in an effort to stop drinking in the city.

“Chicago’s booze lid was clamped down for good last night,” the Tribune declared. “At every cabaret, café, and dry saloon federal agents went on guard at dark and stayed until closing time. Thousands of the regular Saturday night café patrons were examined for flasks and bottles ‘on the hip.’” But of course, the government didn’t have enough manpower to keep up this clampdown for long.46

Meanwhile, mayor Bill Thompson replaced Garrity, the city’s top cop, with his own personal secretary, Charles Fitzmorris, commanding him to “Clear out the crooks!”

“Fitzmorris set out like a whirlwind, as if he really could dig into the complex conditions that produced periodic crime waves and the anarchic state of the police department,” Lloyd Wendt and Herman Kogan wrote in their book Big Bill of Chicago.47

As federal and city authorities clamped down on alcohol sales in Chicago cabarets that fall, fewer people turned out to see cabaret shows. “The effect of the close watch the authorities are keeping on virtually every cabaret in town has already resulted in a marked falling off in patronage and, in consequence, proprietors are cutting down their shows to meet their losses,” the New York Clipper reported.

Mayor Thompson shut down Ike Bloom’s Midnight Frolics and Colosimo’s, at least for the time being (reportedly as an act of political retribution against venue owners opposing Thompson’s favored candidate for state’s attorney). The “girlie” revue at Marigold Garden was let go. And many other venues, including Green Mill Gardens, Edelweiss Gardens, and Dreamland, cut back on their entertainment schedules.48

On December 7, federal prosecutors charged Mann with allowing intoxicating beverages to be sold at Rainbo Gardens—an act that was said to be “against the peace and dignity of the said United States.”49 Agents raided the place and seized two truckloads of whiskey.50

In the months ahead, the U.S. government also bought a civil lawsuit against Mann and Rainbo Garden’s co-owner. Apparently unable to learn the identity of Mann’s true business partner, federal authorities called him “John Doe” in the litigation.51

A witness named Samuel Bell said he’d visited Rainbo Garden on August 28, purchasing one pint of whisky from a waiter for $14. (Adjusted for inflation, that would be roughly $217 in 2024.) According to Bell’s affidavit, “he saw many people served with intoxicating liquor on said premises, said liquor being served to the above said patrons by waiters employed on said premises.”52 Ida Murphy, who was there with Bell and his wife, testified that “she saw a large crowd of people … drinking intoxicating liquor.”53

Mann eventually pleaded guilty to the criminal charge and was fined $100.54 The federal judge in the civil litigation, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, issued a temporary injunction against the owners, “prohibiting them … from conducting the nuisance at 4814 North Clark Street … and from selling, keeping or bartering any intoxicating liquor on the premises.”55

As New Year’s Eve approached at the end of 1920, the U.S. government’s new prohibition commissioner in Chicago, Frank D. Richardson, offered this advice: “Stay at home—go to bed—set the alarm clock for 12 o’clock.” The Daily News predicted a “grape juice bacchanale.”

But many of Chicago’s hotels and cabarets had more reservations for private tables than they’d had a year earlier. Green Mill Gardens had 1,000 reservations; the White City ballroom had more than 5,500; Marigold Gardens, 1,800; Edgewater Beach Hotel, 1,000; Morrison Hotel, 500; Hotel LaSalle, 900; Congress Hotel, 1,000; Sherman Hotel, 2,000; Auditorium Hotel, 400; and Blackstone Hotel, 525.56

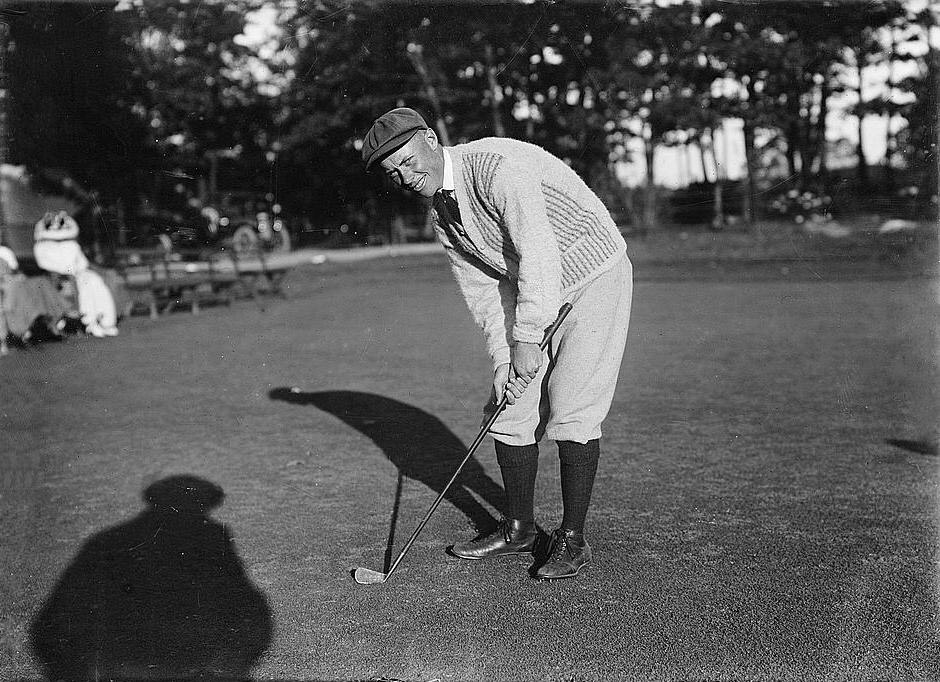

While a crowd was celebrating New Year’s Eve at Green Mill Gardens, federal agents raided the club.57 One of America’s most famous golfers, Chick Evans, had provided evidence against Green Mill Gardens, prompting the raid.

An Indianapolis native who’d grown up on Chicago’s North Side, Charles E. “Chick” Evans Jr. was the first amateur golfer to win both the U.S. Open and U.S. Amateur in one year, a feat he’d accomplished in 1916. And he’d won the U.S. Amateur again in 1920.58

When Evans said he’d purchased a pint of liquor from the manager at Green Mill Gardens, federal authorities had obtained a search warrant to raid the place.59 As it happened, Chick’s brother Elliot H. Evans was the first assistant to Chicago’s prohibition director.60

On January 3, 1921, federal authorities arrested Tom Chamales, along with Green Mill Gardens’ manager, Henry Horn, and several employees, all of whom posted bond and were released: Feodor Kuhn, Eddie Edwards, Gust. Manos, Anthony Reganta, and William “Merres.”61

That last defendant was probably William Boleslaw Meirz, whose name would appear over the years in Green Mill corporation documents, apparently a longtime associate of Chamales. Meirz, whose parents were Polish immigrants, worked as a real estate agent as well as a restaurant cashier, but his main occupation seemed to be bookkeeper: His bookkeeping business, Stibgen & Meirz, had an office in the Green Mill Gardens building as early as 1916.62

Green Mill Gardens’ attorneys told the court that the champion golfer hadn’t actually purchased any booze there. They said one of Evans’s friends gave the liquor to him.63

Evans soon retracted his statement about who’d sold him the alcohol.

“It was explained that Mr. Evans had decided, after making his original statement, that the man who sold him the liquor wasn’t the manager after all,” the Daily News reported.64

Meanwhile, Judge Landis ruled that a search warrant he’d issued in the case was invalid, because it didn’t accurately describe the location of Green Mill Gardens.65

Variety reported: “Tom Chamales and his Green Mill Gardens wriggled out of one of those dangerous indictments before Judge Landis because of the wrong street number being mentioned in the instrument.”66 It’s possible the warrant used the venue’s old address, 4800 North Broadway, where the drugstore was located, rather than the 4804–4810 address that Green Mill Gardens was now using on official documents.

Federal prosecutors dropped all charges.67

By early 1921, the new Chicago police superintendent’s efforts to clean up the department were faltering. “Fitzmorris’ drive slackened after the first fine burst of endeavor,” Wendt and Kogan wrote. “Truck hijackings soon were as plentiful as always, and vice joints flourished under the averted eyes of police captains.”68

PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER

Footnotes

1 “Hunt Bogus U.S. Sleuth as Link in Whisky Ring,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 17, 1920, 17.

2 Matthew Rowley, “The Prohibition Doc Who Prescribed Booze,” Daily Beast, January 18, 2016, updated April 13, 2017, https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-prohibition-doc-who-prescribed-booze.

3 J. Anne Funderburg, “Michigan’s Rum Rebellion,” Michigan History Magazine, November 1, 2016, https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Michigan%27s+rum+rebellion.-a0492464104.

4 “Clearing House of ‘Whisky Ring’ Found by U.S.,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 22, 1920, 17; “May Raid Gold Coast,” Rockford Republic, May 22, 1920, 5.

5 “Dance With Wife, $10,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 28, 1918, 11.

6 “Booze Hunters Net Edgewater Beach Steward,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 27, 1920, 1, 3.

7 “Record of Booze Thefts Shows Huge Stores Are Looted,” Ottawa (IL) Free Trader-Journal, September 4, 1920, 4.

8 “Huge Bootleg Ring Bared by Booze Seizure,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 29, 1920, 1, 4.

9 “$30,000 Whisky Steal Is Laid to Police,” Chicago Daily News, May 22, 1920, 1; “Two Policemen Named in Booze Mystery Theft,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 23, 1920, 1; “U.S. Dry Officers to Probe Rum Mystery,” Chicago Daily News, May 24, 1920, 1.

10 “Huge Bootleg Ring Bared by Booze Seizure,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 29, 1920, 1, 4.

11 “U.S. Records List $1,000,000 Booze Trade by Clancy,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 30, 1920, 15.

12 Associated Press, “Whisky Ring Secrets Known by U.S. Attorney,” Joliet Evening Herald-News, October 23, 1920, 1.

13 United Press, “Assistant U.S. Attorney Attacks Chicago Police,” Freeport (IL) Journal Standard, October 25, 1920, 1.

14 “Quietly Slip Lid on Vice as Expose Looms,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 28, 1920, 1, 4.

15 “Whiskey Ring Within Police Dept. Is Bared,” Streator Daily Free Press, October 2, 1920, 7.

16 National Archives, record group 21, criminal dockets, U.S. District Court for the Eastern (Chicago) Division of the Northern District of Illinois, vol. 13, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/152950802, pp. 135, 504 (PDF 96, 279).

17 “Heitler Booze Plot Case Put in Jury’s Hands,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 6, 1921, 4; U.S. v. Michael Heitler, et al, CR7465, U.S. District Court for the Eastern (Chicago) Division of the Northern District of Illinois, National Archives at Chicago.

18 “Heitler Jury Gets $200,000 Rum Case Today,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 5, 1921 7.

19 “Supreme Court Will Pass on Heitler Case,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 9, 1921, 10.

20 Al Capone’s Beer Wars: A Complete History of Organized Crime in Chicago During Prohibition (Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 2017), 134.

21 Anonymous (John Corbett, ed.), Bullets for Dead Hoods: An Encyclopedia of Chicago Mobsters, c. 1933 (Chicago: Soberscove Press, 2020), 103; Associated Press, “Mike ‘De Pike’ Leitler sic Wrote His Own Death Warrant When He Signed Tell-Tale Letter,” Jacksonville Daily Journal, September 18, 1931, 1; Associated Press, “Capone Hunted in Another Slaying,” Orlando Sentinel, May 3, 1931, 14.

22 “What You Can Do, and What You Cannot Do,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 17, 1920, 2.

23 “32,000 Pints of Whisky a Day Chicago’s Limit,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 12, 1920, 1.

24 “Chicagoan Stirs Druggists Over Booze Selling,” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 24, 1920, 17.

25 Advertisements, Chicago Daily Tribune, August 29, 1920, part 10, 4; September 24, 1920, 25; June 12, 1921, part 10, 2; June 15, 1921, 29.

26 Illinois, U.S., Deaths and Stillbirths Index, 1916-1947, Ancestry.com; “William Charles Weihe,” Find a Grave, accessed January 17, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/169860386/william-charles-weihe.

27 Document 80200559, book 19071, 189; Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

28 “Wrote Message With Lip Rouge,” New York Clipper, May 5, 1920, 23. https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=NYC19200505.2.182&srpos=46&e=——-en-20–41-byDA-img-txIN-%22green+mill+gardens%22———.

29 “Partners to Marry,” New York Clipper, July 21, 1920, 6. https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=NYC19200721.2.34&srpos=52&e=——-en-20–41-byDA-img-txIN-%22green+mill+gardens%22———.

30 Cook County, Illinois Marriage Indexes, 1912-1942; Chamales Family Tree, accessed June 11, 2023; 1900 U.S. Census, Illinois, Cook, Chicago Ward 03, enumeration district 0061, sheet 10A; 1910 U.S. Census, Illinois, Cook, Chicago Ward 2, enumeration district 0179, sheet 1A, Ancestry.com. 1900 Chicago city directory, 1019; 1909 Chicago city directory, 1293, Fold3.com.

31 Max Richard, “Chicago Notes,” Vaudeville News, July 2, 1920, 6. https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=VVN19200702.2.22&srpos=50&e=——-en-20–41-byDA-img-txIN-%22green+mill+gardens%22———.

32 Frank Cullen with Florence Hackman and Donald McNeilly, Vaudeville Old & New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performances in America (New York: Routledge, 2007), 419, https://books.google.com/books?id=XFnfnKg6BcAC&pg=PA419.

33 “Frisco Opens,” New York Clipper, June 30, 1920, 10. https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=NYC19200630.2.93&srpos=49&e=——-en-20–41-byDA-img-txIN-%22green+mill+gardens%22———.

34 “Frisco Ends Engagement,” New York Clipper, July 21, 1920, 10. https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=NYC19200721.2.87&srpos=53&e=——-en-20–41-byDA-img-txIN-%22green+mill+gardens%22———.

35 “Frisco Ends Engagement.”

36 “Partners to Marry.”

37 “The Green Mill Gardens,” Chicago Daily News, August 14, 1920, 10.

38 Bill Edwards, “Paul Biese,” Rag Piano, accessed October 9, 2023, http://ragpiano.com/comps/pbiese.shtml.

39 “Paul Biese Dies Following a Stroke,” La Crosse (WI) Tribune, October 29, 1925, 6.

40 “Garrity Starts Action Against Three Cabarets,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 18, 1920.

41 “sub-deb (n.),” Online Etymology Dictionary, accessed December 11, 2023, https://www.etymonline.com/word/sub-deb.

42 “Rainbo Garden, 2 Others Raided, By Major’s Men,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 10, 1920, 17.

43 “Revenue Agents Raid Rainbo, Green Mill,” Chicago Daily News, October 9, 1920, 1, 3.

44 “Maj. Dalrymple Quits Prohibition Post,” New York Times, October 29, 1920, 9, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1920/10/29/102906032.html?pageNumber=9.

45 “Frank D. Richardson Gets Dalrymple Job,” Chicago Daily News, November 5, 1920, 1.

46 “U.S. Slaps on Booze Lid,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 7, 1920, 1, 2.

47 Lloyd Wendt and Herman Kogan, Big Bill of Chicago (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1953; Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2005), 192.

48 “Chicago Raids to Close Most All City Cabarets,” New York Clipper, December 1, 1920, 7. https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=NYC19201201.2.58&e=——-en-20–61-byDA-img-txIN-%22green+mill+gardens%22———.

49 National Archives, record group 21, criminal dockets, U.S. District Court for the Eastern (Chicago) Division of the Northern District of Illinois, vol. 13, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/152950802, 266 (PDF p. 160). Indictment, filed Dec. 7, 1920, United States v. Fred Mann, CR7450, U.S. District Court for the Eastern (Chicago) Division of the Northern District of Illinois, National Archives at Chicago.

50 “Landis Orders Booze Sale at Rainbo Stopped,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 6, 1921, 25.

51 Equity case docket books; Action to enjoin nuisance, Equity 2012, U.S. v. Fred Mann and John Doe.

52 Samuel Bell affidavit, Equity 2012, U.S. v. Fred Mann and John Doe.

53 Ida Murphy affidavit, Equity 2012, U.S. v. Fred Mann and John Doe.

54 Criminal dockets.

55 Temporary injunction, Equity 2012, U.S. v. Fred Mann and John Doe.

56 “Grape Juice Ready? Let the New Year In,” Chicago Daily News, December 31, 1920, 1.

57 “Hold 3 in Green Mill Raid,” Chicago Daily News, January 3, 1921, 1.

58 “Chick Evans,” Wikipedia, accessed October 10, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chick_Evans.

59 Associated Press, “‘Chick’ Evans Must Tell of Booze Sale,” (Rockford, IL) Daily Register-Gazette, Jan. 15, 1921, 4.

60 “Landis Shuts 17 Bars …,” Chicago Daily News, January 15, 1921, 1.

61 United States vs. Thomas Chamales, et al, Commissioner case 7343, 1921, U.S. District Court, Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division, U.S. Commissioner’s Dockets, Commissioner Mason (Commissioner Lewis F. Mason, Cases 7200-7399, Container 89), National Archives, Chicago.

62 1916 Chicago city directory, 1279, Fold3.com; World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918; 1930 U.S. Census, Illinois, Cook, Chicago (Districts 1251-1500), enumeration district 1444, sheet 8A; Illinois, U.S., Deaths and Stillbirths Index, 1916-1947, Ancestry.com.

63 “‘Chick’ Evans Must Tell of Booze Sale.”

64 “‘Chick’ Evans Takes It Back,” Chicago Daily News, April 4, 1921, 3.

65 “27 Cases Booze Vanish Under Eyes of U.S. Men,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 5, 1921, 10.

66 “Green Mill in Luck,” Variety, February 18, 1921, 9, https://archive.org/details/variety61-1921-02/page/n103/mode/2up.

67 United States vs. Thomas Chamales, et al, Commissioner case 7343.

68 Wendt and Kogan, Big Bill of Chicago, 199.