CHAPTER 24 of THE COOLEST SPOT IN CHICAGO:

A HISTORY OF GREEN MILL GARDENS AND THE BEGINNINGS OF UPTOWN

PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER

Sex! Jazz! Booze! Beaches! Shopping! Movie palaces! Chicago’s Uptown had it all.

During the Roaring Twenties, people flocked to the neighborhood when they wanted to have fun. “If you seek amusement, Uptown Chicago has long been famed for its unrivaled facilities for pleasure indoors and out,” the local business association declared.1

The neighborhood was dominated by people in their 20s and 30s, most of them renting apartments or living in hotels and boardinghouses.2 As one Chicagoan observed, the young families “who want home life and children” moved to neighborhoods like Albany Park, but “those who want to have ‘a good time’ go to Wilson Avenue.”3

Whenever a young single woman left a small farm town and headed to Chicago to plunge into the excitement of big-city life, “she inevitably bobs up in the Wilson district,” one reporter observed about Uptown, which was commonly known then as the Wilson Avenue District.4 Women outnumbered men in the neighborhood—there were 11 females for every nine males, according to my analysis of the 1920 census.5

And Uptown was sexy. In Meyer Levin’s novel The Old Bunch, a character had this to say about the neighborhood: “Were the broads hot around there!”6

In one 1928 story, a married woman heads to Uptown when she sets out on a quest for extramarital adventures. “Wilson Avenue and its environs have both a local and national reputation as the playground of the dissolute—those on amusement bent,” she says. “Therefore, I wended my way in that direction.”7

Of course, not everyone approved of the neighborhood’s tendency for licentious behavior. The Northside Sunday Citizen newspaper bemoaned the area’s reputation as “Chicago’s world-famed ‘Pick Up Paradise.’”8 And a sociologist’s study determined that the Wilson Avenue District was Chicago’s capital of divorces and spousal desertions.9

The corner of Wilson Avenue and Sheridan Road was a hive of nightlife activity, a meeting place for people going out for an evening of high jinks. The Citizen’s reporter said he’d often seen an “automobile sheik reaping a harvest” at Sheridan and Wilson, picking up female “cargo.” These male motorists seeking young women were so numerous that they practically blocked traffic in the intersection.

The reporter suggested what might happen to these young women after they were taken for a ride: “They may be accompanied home, they may lay their dainty head to sleep in some road-side ditch, or perchance the party will terminate at some inconsiderate police station. In any event life is short—so on with the dance!”10

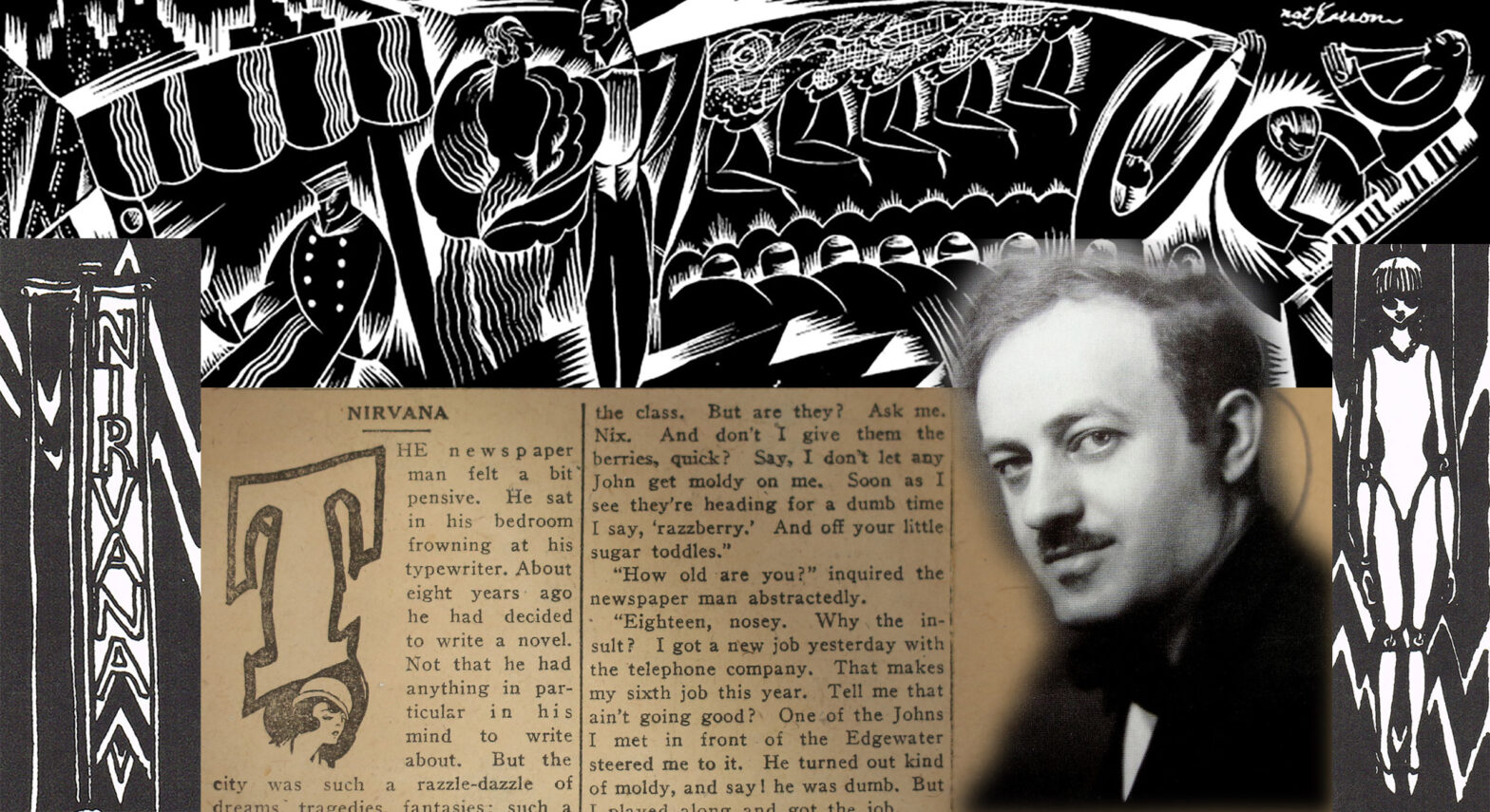

In August 1921, legendary Chicago journalist and author Ben Hecht wrote about a newspaperman—almost certainly a character based on himself, or maybe some of his newsroom colleagues—who restlessly walks the streets of Chicago one night, ending up at Wilson and Sheridan.

“Here the loneliness he had felt in his bedroom seemed to grow more acute,” Hecht wrote. “Not only his own aimlessness, but the aimlessness of the staring, smiling crowd afflicted him.”

This was where Hecht’s protagonist runs into a young woman, who recognizes him from a previous encounter. Or maybe it’s more appropriate to call her a girl—she tells him that she’s a mere 18 years old. She’s a chatty and flirtatious flapper—a type of female who would become an iconic symbol of the Roaring Twenties.

And if Hecht’s description was accurate, this youngster may have been a fairly typical female resident of Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood in the early 1920s. Hecht continues:

Then out of the babble of faces he heard his name called. A rouged young flapper, high heeled, short skirted and a jaunty green hat. One of the impudent little swaggering boulevard promenaders who talk like simpletons and dance like Salomes, who laugh like parrots and ogle like Pierettes. The birdlike strut of her silkened legs, the brazen lure of her stenciled child face, the lithe grimace of her adolescent body under the stiff coloring of her clothes were a part of the blur in the newspaper man’s mind. …

“Wilson avenue,” he thought, as he walked beside her chatter. “The wise, brazen little virgins who shimmy and toddle, but never pay the fiddler. She’s it. Selling her ankles for a glass of pop and her eyes for a fox trot. Unhuman little piece. A cross between a macaw and a marionette.”11

Flappers like this weren’t the only reason so many people found Uptown to be a fascinating, incredible place. “If you would see life as it is lived nowhere else on the face of the earth, build yourself a shack in the Wilson avenue district,” the Citizen suggested.12

The Chicago novelist Edwin Balmer called it “a neighborhood as remarkable as any in America.” To Balmer, it seemed like no one had lived in Uptown for very long. “Impermanency is in the air of the quarter,” he wrote.13

But amid all of the fresh faces constantly arriving in Uptown, a handful of people could say they’d lived in this vicinity for years or even decades, going back to the days when it was rural countryside on the fringes of Chicago. One of those longtime residents, Fred Dale Wood, was proud of this city within a city that had sprung up around him.

“Uptown Chicago is to me the finest place in all the world,” he remarked in 1923. “… Within its boundaries is everything for pleasure, comfort, happiness and business activities that can be desired. At its door is one of the world’s greatest lakes, a playground of majestic grandeur. … It is growing so rapidly that one must visit it almost every day to keep pace with it.”14

When Wood called it “Uptown Chicago,” he was using a fairly new phrase. The Chicago neighborhood we call Uptown finally got that name in the early 1920s, although many people continued calling it the Wilson Avenue District.

It had been part of Lake View before Chicago annexed that suburb in 1889. A Sanborn fire insurance map from 1894 showed several neighborhood and subdivision names in the vicinity—Buena Park, Ravenswood, Summerdale, and Argyle—but no Uptown.15 Another section was called the Sheridan Drive Subdivision, which became Sheridan Park.16 In the years after 1910, newspapers often referred to this general area as the North Shore.

Loophounds—people who frequented downtown saloons—referred to Uptown as Little Paris, the Tribune mentioned in 1919.17

That was also the nickname used by thieves, according to Balmer’s 1925 novel, That Royle Girl: “The merchants of the sunny, agreeable streets, feeling their distinction and seeking to denote it, have called the new city ‘the uptown.’ Its thieves, more poetic and far more sensitive to essentials, speak of it as ‘Little Paris.’”18

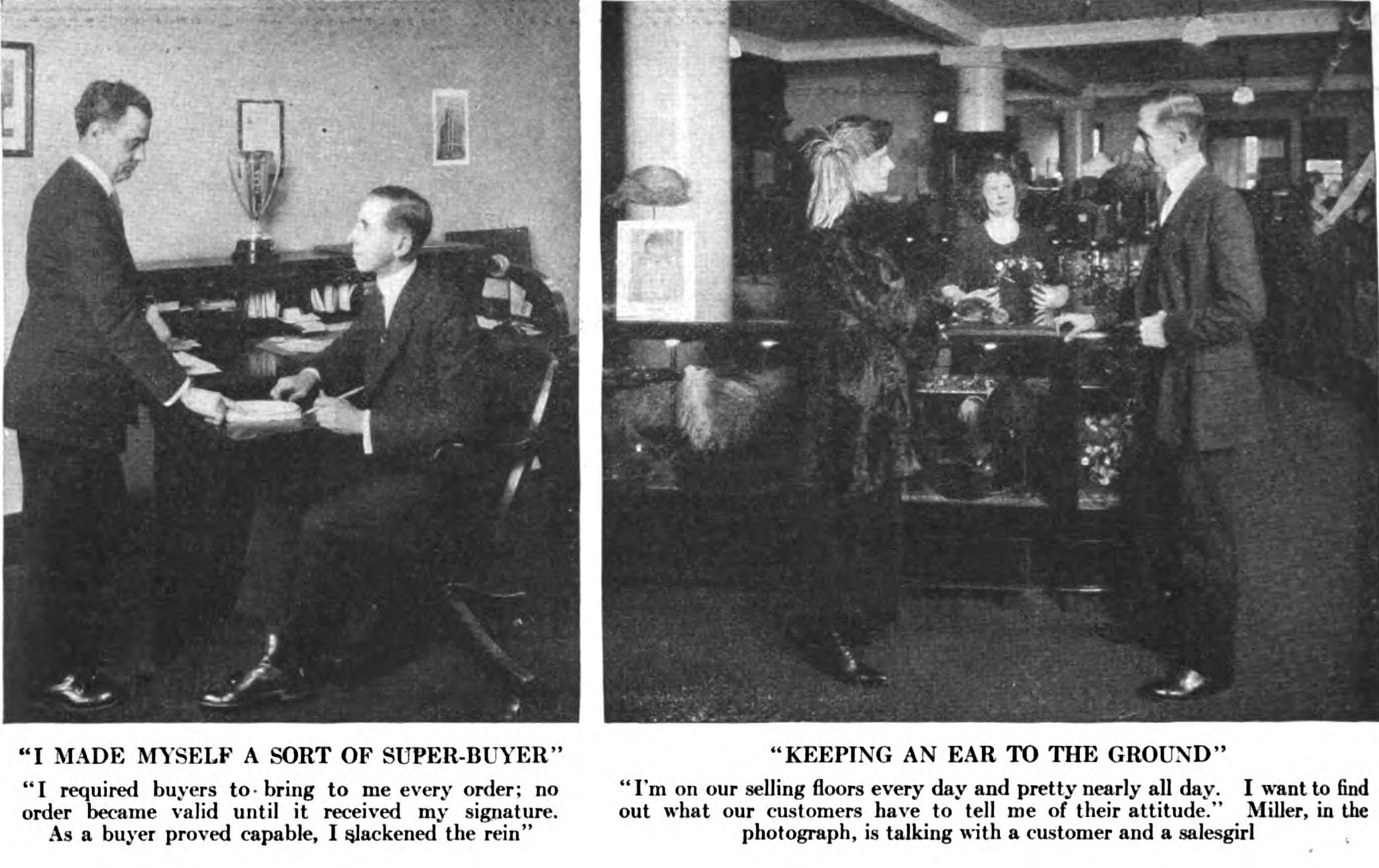

A businessman named Loren Miller had started calling it Up-Town around 1915, when he opened a department store at 4720 North Broadway. Before going into business for himself, Miller had worked as a buyer for Marshall Field in Chicago’s Loop, commuting downtown from his home on Leland Avenue near the lakefront. Miller himself referred to the neighborhood where he lived as “the North Shore.”19

System: The Magazine of Business, May 1921

“Since the day I moved to the North Shore in 1906, I have felt that there was absolutely no doubt about the district growing to be one of the finest residential and business sections in any large city in America,” Miller said.20 The neighborhood was growing rapidly at the time, thanks in part to the opening of the Northwestern Elevated railroad line in 1900, connecting Wilson Avenue with downtown Chicago.

Miller came up with the idea of opening a large store to serve the people who lived around him, especially the housewives. He later recalled giving this little speech to his next-door neighbor, the diamond merchant R.C. Abt:

“I tell you, Abt, there’s a gold mine in this locality for any live business man who has the money and the nerve to start a real department store here. There’s money here, with at least a quarter of a million people all in a bunch, and all drawing good salaries, or making good profits out of some business, or just living on the income of what they have.

“It’s plumb foolishness to say that our wives and daughters yearn to travel five or six miles into town to buy dry goods, or even millinery, or coats and dresses. They simply don’t yearn. The ancient fetish of shopping was wished on women in the days when there were so few variations in patterns and prices that getting a bargain was a triumph and getting one’s choice was a pleasure. Nowadays, it’s killing hard work—nothing less.

“Of course, I’m willing to admit that a trip downtown affords them an excuse for taking out the auto mobile and feeling distinguished when they alight from it. But with maids becoming harder to get than ever, and with traffic downtown congesting until it promises to end in a daily deadlock, women prefer going just around the corner for most of the things they need. Anyway, the majority haven’t cars. The female population of this whole North Shore section is in the mood to want what they want when they want it; and I could ask for nothing better than to be the man to give it to them.”

Abt put Miller in touch with another neighborhood resident, banker W.J. Klingenberg, who was planning a new building for his Sheridan Trust and Saving Bank. The new bank would go up at the north point of the triangular block bounded by Broadway, Racine Avenue, and Leland Avenue—a bit south of Green Mill Gardens.

Miller worked out a deal with Klingenberg to build his department store just south of the new bank.

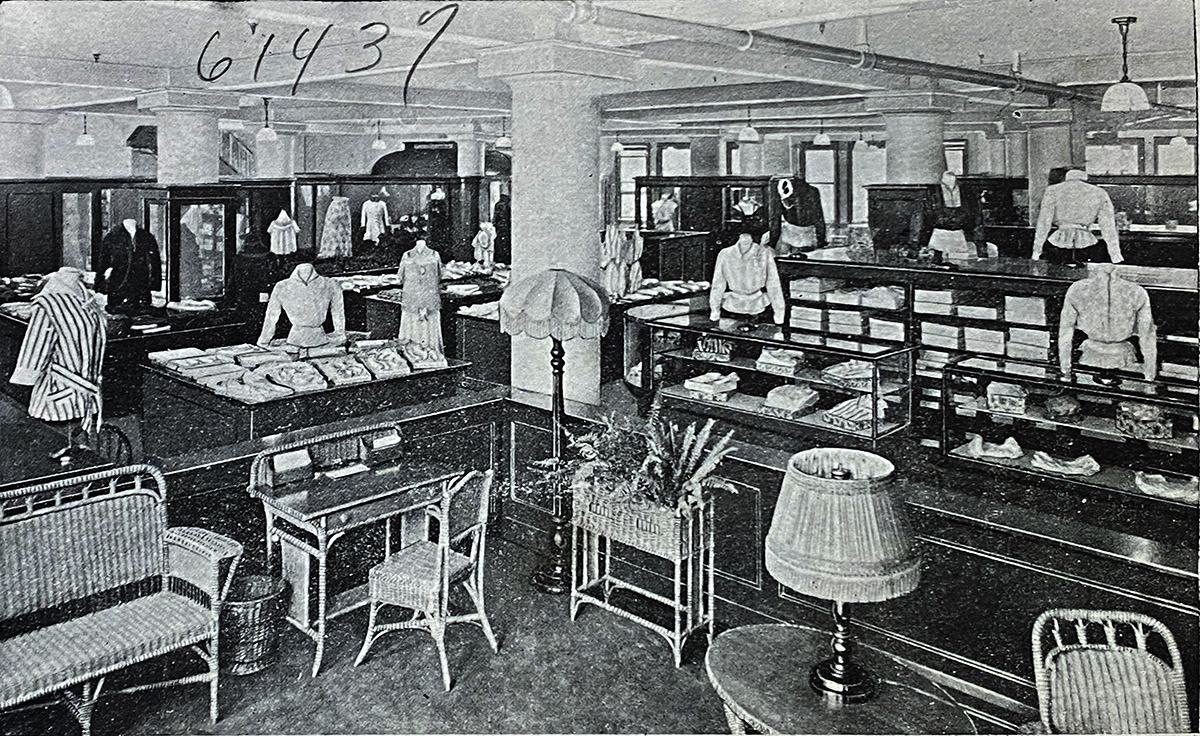

The Loren Miller & Co. Department Store, a five-story terra-cotta-clad emporium, opened for business on November 22, 1915.

Loren Miller & Co. (Exterior). A61436, Records of the Curt Teich Company, Newberry Library.

In promotions and advertisements, Miller started using “Up-Town” as a description of his store’s location.

“That particular phrase held a very important trade implication—that up-town was the aristocratic antithesis of down-town,” Miller later wrote, “and it brought home to every North Shore resident the sensation of making a needless journey down-town …”

To put it another way, Miller believed the word uptown (which eventually lost that hyphen) would remind people that they were some distance away from downtown. And when people were reminded about that, they’d think about how much easier it would be to go shopping right in their own uptown neighborhood instead of taking a trip down to the Loop.

Loren Miller & Co. (Interior). A61437, Records of the Curt Teich Company, Newberry Library.

The shopping district around Miller’s store boomed over the following decade. Uptown was one of some two dozen commercial centers popping up at major intersections around Chicago’s neighborhoods. Uptown also became the biggest entertainment district outside of the Loop.21

Ben Hecht Papers, Newberry Library

In Ben Hecht’s story about the newspaperman who hooks up with a flapper at Wilson and Sheridan, the couple goes into “a cabaret in the neighborhood.” Is Hecht describing Green Mill Gardens? Possibly. The Green Mill was just a short walk from Wilson and Sheridan. But it wasn’t the only nearby cabaret. The newspaperman and the flapper might have gone, for example, to the Arcadia, near Montrose and Broadway. Or Rainbo Garden, at Clark and Lawrence—although that would have been a bit more of hike.

And it’s hard to say how much of this story, which the Chicago Daily News published as part of Hecht’s series “Around the Town: A Thousand and One Afternoons in Chicago,” was true and how much was embellishment or outright fiction. Hecht’s editor, Henry Justin Smith, said these columns were “stories seemingly born out of nothing … but in reality, as a rule, based upon actual incident, developed by a period of soaking in the peculiar chemicals of Ben’s nature, and written with much sophistication in the choice of words.”22

In any case, Hecht offers a literary evocation of the atmosphere in Uptown’s cabarets, circa 1921:

The orchestra filled the place with confetti of sound. Laughter, shouts, a leap of voices, blazing lights, perspiring waiters, faces and hats thrusting vivid stencils through the uncoiling tinsel of tobacco smoke.

On the dance floor bodies hugging, toddling, shimmying; faces fastened together; eyes glassy with incongruous ecstasies.

The newspaper man ordered two drinks of moonshine and let the scene blur before him like a colored picture puzzle out of focus.

The flapper is the real focus of Hecht’s column. At the time, Americans were fascinated by these young women—or outraged about them. The word flapper had become slang for “a young girl” around 1888. Circa 1915, it took on a new meaning: “a stylish, brash, hedonistic young woman who flouts conventional behavior.”23

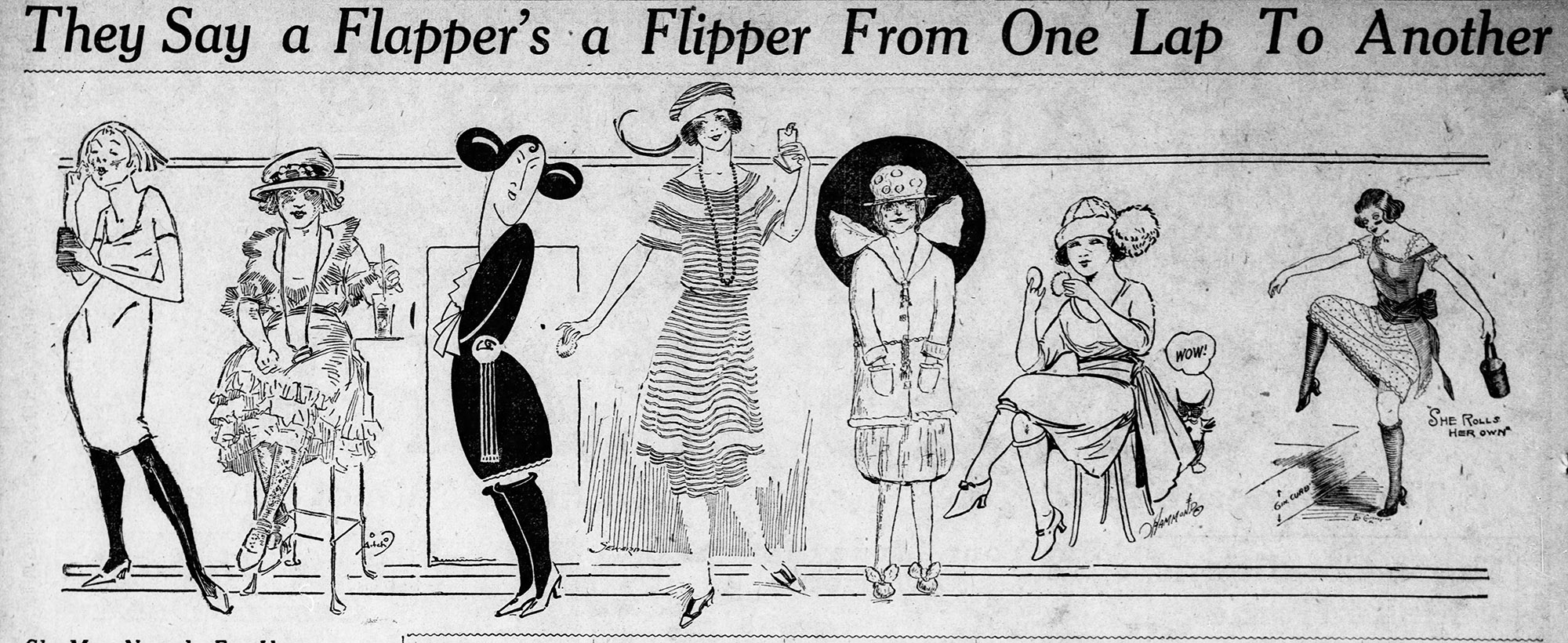

On the same week in August 1921 when the Daily News published Hecht’s tale of a night out with a flapper, a newspaper in Kansas tried to answer the burning question on many people’s minds: What, exactly, is a flapper? The Wichita Daily Eagle commissioned several artists to draw a typical flapper:

Wichita Daily Eagle, August 21, 1921.

The newspaper offered this distillation of the conventional wisdom about flappers:

The unanimous opinion of men and women of Wichita is that—

Flappers must never be FAT.

They must love attention—

And HATE chaperones.

They must be exceedingly young.

(Somewhere between 16 and 20)

And wear bobbed hair.

Flappers should be clothed in

Short dresses and LOTS of rouge.

They must absolutely ADORE

Lemon cokes and soda squirts—

And not have a speck of gray-matter.

Expanding on the theme, the Daily Eagle continued: “The flapper is young and like a young butterfly just emerged from its chrysalis, her wings must be beautiful. Clothes are her main concern. They must be new and bizarre and scintillating. They must dazzle and charm. She’s a cute little thing, this flapper, with no other thought than to live life to the fullest, give nothing in return and still be gay. Underneath it all, oft-times, there’s a smouldering longing to be brainy and reliable and valuable to some body or something. But she can’t make it, she knows, so she goes ahead, and smiles and dances and flirts.”24

The following year, a writer in Virginia addressed the question “What Is a Flapper?” by offering this scientific definition, which satirized common attitudes:

The Flapper; Sui generis, Americani girli. Habitat, dance halls, moving picture theatres, barbershops and streets, in cities and towns; is occasionally found in the country, usually at road-houses.

Feminine gender and in some respects resembles a human woman in that it has a body, limbs, hands and feet shaped like hers, and it walks erect. The apparently exaggerated size of the head is due to a hair-like growth covering it, which is cut short and manipulated in some mysterious manner to make it stand out …

The face has an unhealthy, ashy look, with a streak of crimson around the mouth, a thread of deep black above each eye and is utterly devoid of expression. …

The creature has ears shaped like a human being, of which it is ashamed, for it conceals them under the bobbed hair; this sense of shame, however, does not extend to the knees, for they are frequently freely exhibited, the hose being sometimes rolled below them to insure an unobstructed view; very little clothing is worn on any portion of the body.

The flappers have a means of communication among themselves and their male-kind, in which an occasional sound indicates that it may have been deprived from the English tongue, but most of it is unintelligible.

All joking aside, the same writer concluded that a flapper “is merely a live, normal, up-to-date American girl in an abnormal environment.”25

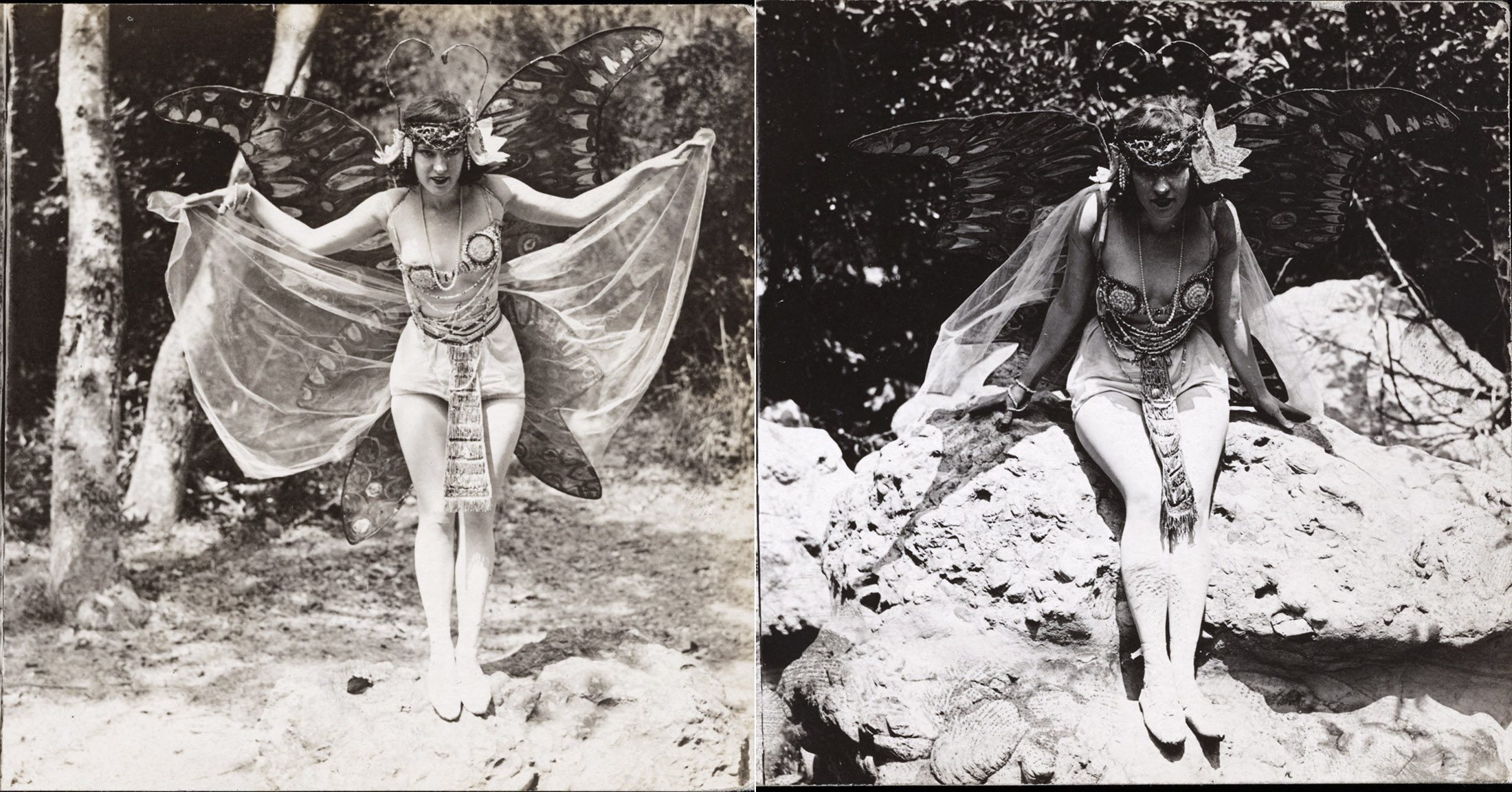

Meanwhile, the Exhibit Supply Company capitalized on the American fascination with flappers. The Chicago company, which published naughty stereoscopic photos (now digitized by the Library of Congress), sometimes featured “flappers.” These 1923 photos supposedly depicted “The Flapper,” although it’s questionable how many actual Chicago flappers of the early 1920s were dressed like this:26

“The Flapper” (Chicago: Exhibit Supply Company, 1923), https://www.loc.gov/item/2023638740/, https://www.loc.gov/item/2023638741/.

Another set of photos from 1923 humorously told the story of “Making a Flapper Out of Mother”:27

“Making a Flapper Out of Mother” (Chicago: Exhibit Supply Company, 1923),

https://www.loc.gov/item/2023638488/, https://www.loc.gov/item/2023638489/.

When the Chicago Daily News published Hecht’s column, the only illustration was a thumbnail-size drawing of the flapper from the neck up, wearing that “jaunty” hat. In this simple line drawing (which was stuck onto the bottom of a big letter “T”), her expression is hard to read. Guarded. Blasé.

When Hecht’s column was republished in the original 1922 book 1001 Afternoons in Chicago, it had a weirder illustration, showing a quite different female figure.

Below her head—with its cavernous, dark eyes—her body hangs limp, like the unadorned wooden segments of a mannequin, an image Hecht had evoked. This picture by artist Herman Rosse seemed to envision the flapper as more of a sexual object.28

Below her head—with its cavernous, dark eyes—her body hangs limp, like the unadorned wooden segments of a mannequin, an image Hecht had evoked. This picture by artist Herman Rosse seemed to envision the flapper as more of a sexual object.28

Much of the alarm and outrage about flappers focused on sexual promiscuity. And some people worried that Uptown’s young female residents would fall into a life of prostitution.

It might seem telling that the flapper in Hecht’s column uses a piece of lingo usually associated with prostitutes: She talks about the “Johns” she has gone out with. But it was common for people to say “John” as a generic term for a man. By the early 1920s, “John” was sometimes used as slang for “a gullible wealthy man who keeps or seeks a mistress, especially a showgirl or prostitute.” Within a few years, the word started being used in the more general sense of a “male customer of a prostitute.”29 When the flapper in Hecht’s story refers to “fancy Johns,” she seems to be seeking out wealthy men who will foot the bill for her to have a fun night out on the town.

Here is Hecht’s narrative of the flapper’s conversation with the newspaperman. It’s really more of a monologue, with the female doing nearly all of the talking.

Above the music he heard the childishly strident voice of the flapper:

“Where you been hiding yourself? I thought you and I were cookies. Well, that’s the way with you Johns. But there’s enough to go around, you can bet. Say boy! I met the classiest John the other evening in front of the Hopper. Did he have class, boy! You know there are some of these fancy Johns who look like they were the class. But are they? Ask me. Nix. And don’t I give them the berries, quick? Say, I don’t let any John get moldy on me. Soon as I see they’re heading for a dumb time I say ‘razzberry.’ And off your little sugar toddles.”

“How old are you?” inquired the newspaper man abstractedly.

“Eighteen, nosey. Why the insult? I got a new job yesterday with the telephone company. That makes my sixth job this year. Tell me that ain’t going good? One of the Johns I met in front of the Edgewater steered me to it. He turned out kind of moldy, and say! he was dumb. But I played along and got the job.

“Say, I bet you never noticed my swell kicks.” The flapper thrust forth her legs and twirled her feet. “Classy, eh? They go with the lid pretty nice. Say, you’re kind of dumb yourself. You’ve got moldy since I saw you last.”

“How’d you remember my name?” inquired the newspaper man.

“Oh, there are some Johns who tip over the oil can right from the start. And you never forget them. Nobody could forget you, handsome. Never no more, never. What do you say to another shot of hootch? The stuff’s getting rottener and rottener, don’t you think? Come on, swallow. Here’s how. Oh, ain’t we got fun!”

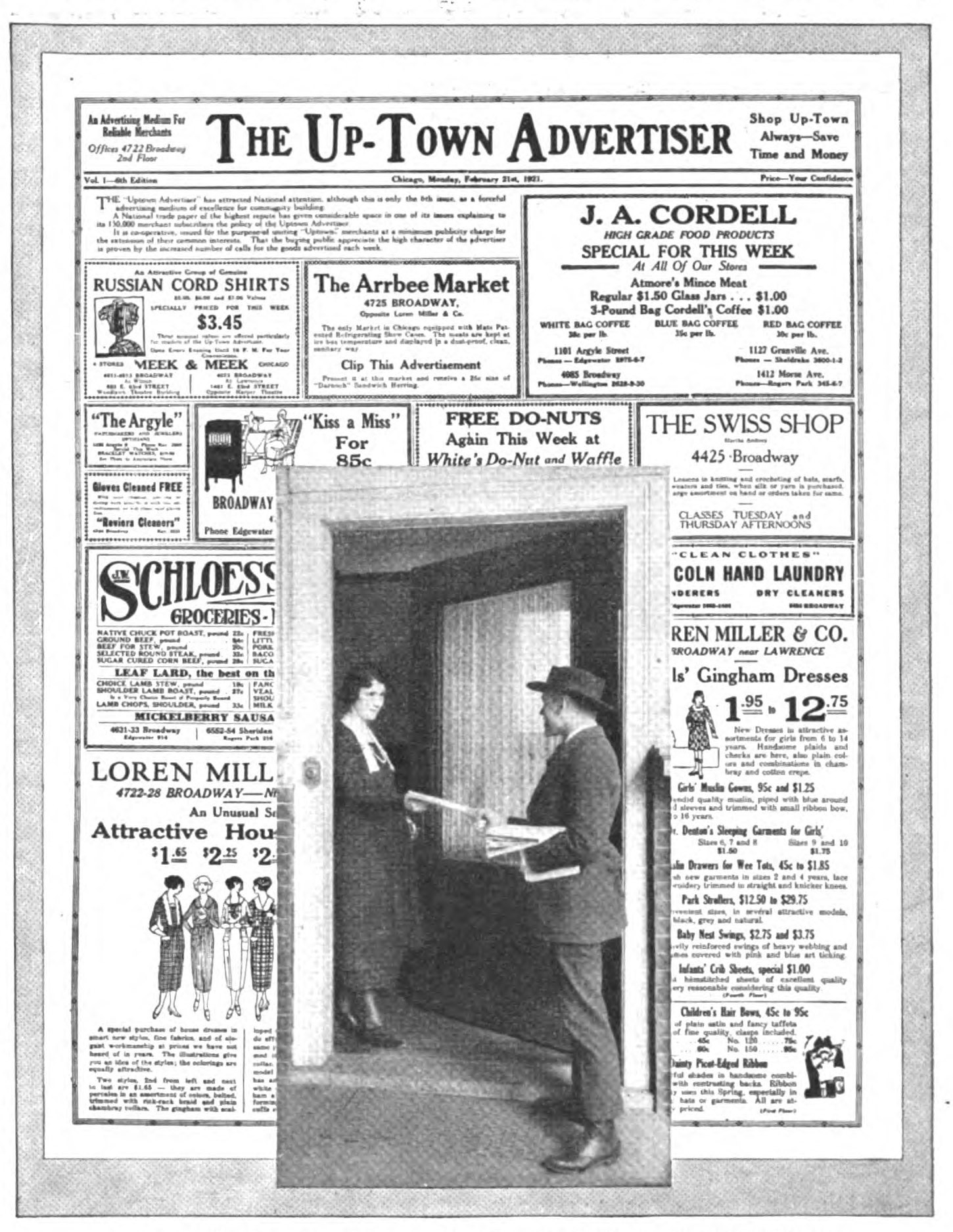

The department store magnate Loren Miller conducted what he called a “propaganda” campaign to establish Uptown’s identity. For five years, he delivered advertising circulars for his store to 53,000 homes in the vicinity.

Starting on January 17, 1921, he expanded the circular into a publication called The Up-Town Advertiser, including ads for other neighborhood merchants alongside the ones for his own store.

However, this publication also used the North Shore name. An early issue remarked: “The spirit of the North Shore community has brought banking facilities that are unsurpassed, theaters that are worthy of our pride, hotels that offer every convenience and comfort, business houses that bring almost next door, complete stocks of every needed commodity.”

By 1921, the Loren Miller & Co. Department Store was making $1 million in annual sales (the equivalent of $17 million in 2024). And it was getting ready to expand into the bank building immediately north of it, as the Sheridan Trust and Saving Bank prepared to move into a much larger tower under construction across the street, at the southeast corner of Broadway and Lawrence Avenue.30

When the 12-story Sheridan Plaza Hotel opened in April 1921 at the northwest corner of Wilson Street and Sheridan Road—becoming the neighborhood’s tallest building31—the Daily National Hotel Reporter said it was located in the “Junior Loop.”32 The neighborhood was starting to seem a bit like a miniature version of the Loop.

The word “Uptown” began appearing as a name for the neighborhood in newspapers in 1921. An ad for Sheridan Trust and Savings Bank called itself the “Oldest and Largest in Uptown Chicago.”33 An ad for Loren Miller & Co. called it “The Popular Uptown Chicago Store.”34 Another notice offered a store for rent in “the new uptown business district.”35

In November 1921, Loren Miller elected as the president of a new business group called the Uptown Chicago Association.36

And in May 1922, the Daily National Hotel Reporter said that the Sheridan Plaza Hotel had a “very central location in the new ‘Uptown Chicago.’”37

The area’s business group officially incorporated at the end of 1923 as the Central Uptown Improvement Association.38 Not long after that, advertisements began referring to the neighborhood as “Central Uptown,”39 a name that seemed to suggest it was just the central portion of some larger expanse known as Uptown.40

But the Uptown name did not become firmly established overnight. When Northwestern University sociology student Harold Charles Hoffsommer wrote a thesis about the area in 1923, he chose to call it the Wilson Avenue District. According to Hoffsommer, that was what most local residents called it. He said people used other names, too: the Up Town Section, the Junior Loop, the North Shore Loop, the Hub of Uptown Chicago, and the Wonder Street.

Loren Miller believed that the corner of Broadway and Lawrence Avenue was Uptown’s business center. But Hoffsommer wrote: “The most popular opinion, however, is that the center is at the intersection of Broadway and Wilson Avenue.” As he pointed out, Broadway and Wilson was where the neighborhood’s building boom had originally started, near the elevated station.

But in the years since then, more and more businesses had opened farther north, along Broadway and along Sheridan Road. “Recent developments along Lawrence Avenue might lead one to suspect that eventually the business center will be located there,” Hoffsommer commented.41 He also noted that an “automobile row” was forming on Broadway north of Lawrence, as automobile-related businesses opened in that stretch.42

On June 18, 1924, the Chicago City Council voted to designate the intersection of Broadway and Racine Avenue—essentially, the space just south of where Broadway meets Lawrence Avenue—as Uptown Square.43

The opening of the Uptown Theatre in 1925—with giant signs displaying the name “UPTOWN” looming over Broadway and Lawrence—surely helped to solidify the public perception that this place was called Uptown.

As that movie palace opened, Uptown had earned its reputation as a bustling place where residents from quieter neighborhoods visited to go shopping, dining, or dancing. A resident of nearby Ravenswood told the Daily News that he preferred the quiet, tree-lined streets of his own neighborhood, but he was glad that “‘Uptown’ theaters and beaches are but a step away.”44

An Edgewater resident expressed a similar thought about his own neighborhood’s proximity to Uptown: “Bordering the busy uptown district, and yet a decided contrast to it in the matter of noise, Edgewater residents are close to every kind of amusement.”45

In 1927, the Central Uptown Chicago Association spent $150,000 (roughly $2.7 million, adjusted for inflation) on an advertising campaign designed to “put Uptown Chicago on the map and keep it there.”46 The business group called it “Uptown Chicago,” never simply “Uptown.” Its newspaper ads said the area was the “Shopping Center of a Million People”47 and a “great City within a City.”

These ads also included a simple explanation of Uptown’s boundaries: It was north of Montrose Avenue, east of Clark Street, south of Argyle Street, and west of Lake Michigan. 48

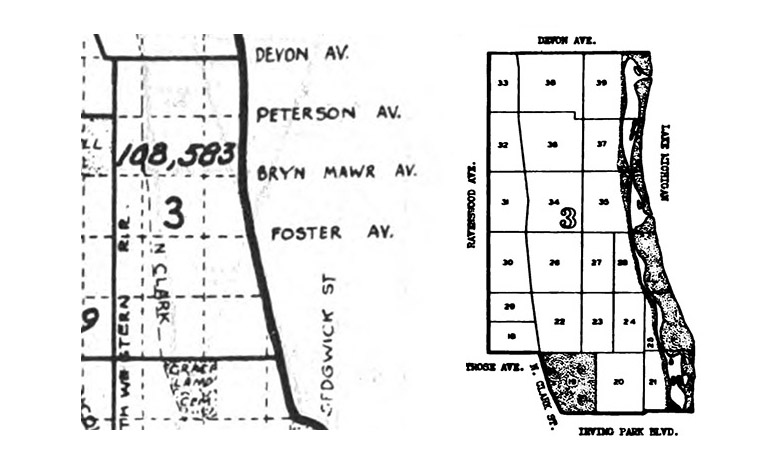

But University of Chicago researchers decided that Uptown encompassed a larger area when they drew up maps in 1929 dividing the city into 75 “community areas.” One early version of the map did not include the Buena Park neighborhood, south of Montrose Avenue, as part of Uptown49—but another version of the map did, and that’s the one that became established as the definitive one.50

The U. of C.’s mapmakers also used Ravenswood Avenue as Uptown’s west boundary, pulling in a swath of what most people might have called the Ravenswood neighborhood. And they used Devon Avenue as the north boundary—essentially declaring that the distinct neighborhood of Edgewater was just another section of Uptown.51 This would prove to be a controversial move. Decades later, after the Uptown moniker had lost its glamour, Edgewater seceded from Uptown in 1980, becoming its own community area.52

“Those who sought a separate community area designation for Edgewater (and I was among them) sought it not in revulsion toward an Uptown that was undergoing some difficult times, but rather as a righting of a wrong that was committed by University of Chicago sociologists in merging Edgewater into Uptown in the 1920s and eliminating its name and identity,” LeRoy Blommaert wrote in a 2007 letter to the Chicago Reader.53

To this day, it’s debatable precisely where Uptown begins and ends.

Ben Hecht often wrote about women like the flapper in Uptown. “The young woman adrift in the city, the countless sisters of Sister Carrie, appear throughout this work,” Bill Savage wrote in an introduction to a 2009 edition of the book collecting Hecht’s columns, 1001 Afternoons in Chicago. “Hecht doesn’t impose either the conventional morality of the day or take the easy exit of ‘free love,’ but instead tries to imagine and depict what it must like to be her.”54

Hecht continued this column with more of the newspaperman’s musings about the young woman he is sitting with in that anonymous Uptown cabaret:

The orchestra paused. It resumed. The crowd thickened. Shouts, laughter, swaying bodies. A tinkle of glassware, snort of trombones, whang of banjos. The newspaper man looked on and listened through a film.

The brazen patter of his young friend rippled on. A growing gamin coarseness in her talk with a nervous, restless twitter underneath. Her dark child eyes, perverse under their touch of black paint, swung eagerly through the crowd. Her talk of Johns, of dumb times and moldy times, of classy times and classy memories varied only slightly. She liked dancing and amusement parks. Automobile riding not so good. And besides you had to be careful. There were some Johns who thought it cute to play caveman. Yes, she’d had a lot of close times, but they wouldn’t get her. Never, no, never no more. Anyway, not while there was music and dancing and a whoop-de-da-da in the amusement parks.

The newspaper man, listening, thought, “An infant gone mad with her dolls. Or no, vice has lost its humanness. She’s the symbol of new sin—the unhuman, passionless whirligig of baby girls and baby boys through the cabarets.”

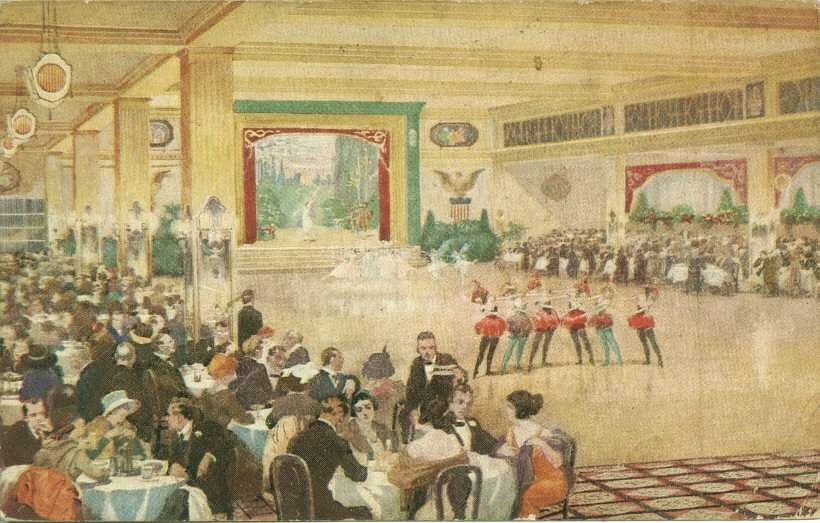

The nightclub in Hecht’s story also might have been Marigold Gardens, which was just outside the Uptown neighborhood, located on Grace Street west of Broadway and Halsted Street, in Lake View. Marigold (formerly known as Bismarck Gardens) was often mentioned in the same breath as Green Mill Gardens and Rainbo Garden. They were the three big “amusement gardens” on Chicago’s North Side.

Edwin Balmer was clearly inspired by these places when he wrote about a fictional venue called Echo Garden somewhere in the vicinity of Uptown—a club that was visible if you looked south from Wilson Avenue Beach. In That Royle Girl, Balmer offered a sample of how these venues’ jazz musicians supposedly spoke.

“I got to steppin’ on a new trot,” says Fred Ketlar, Echo Garden’s popular young bandleader, describing how he came up with a new melody. “… it’s a riot. Got the moan of it ’bout ten o’clock when I was tramplin’ on the Danube Blues and I blew it on the sax for the encore while Henny jazzed the old Blues. Honest, they wouldn’t let me sit down.” This musician proclaims that his new tune is “a zizz,” while scornfully dismissing another piece of music he hears on the radio as “Something punk. Nothing of mine.”

In Balmer’s novel, the police accuse Ketlar of murdering his wife. Some people riding on the elevated to Wilson Avenue discuss the case as they look at a newspaper. “Ever slapped the sole to this bird’s jazz?” one asks. The other replies: “Have I! Give a girl a choice and she’s got to go where Ketlar is playin’. Some sheik, that baby.”55

Marigold Gardens was the setting for a 1920 poem by Carl Sandburg, called “Balloon Faces.” The title refers to decorative balloons hanging on wires in the venue’s garden area, with “faces” that seemed float in the sky. As Sandburg observes the people dining at Marigold, he suggests that their faces resemble the balloons—he calls them “balloon face eaters” and “heavy balloon face women.”

While Sandburg offers a more contemplative vision of North Side nightlife than the hectic scene reported by Hecht, it’s easy to imagine the two of them—both were writers for the Chicago Daily News—sitting in the same cabaret and making mental notes about the people surrounding them. Sandburg describes overheard conversations in the café:

Poets, lawyers, ad men, mason contractors, smart alecks discussing “educated jackasses,” here they put crabs into their balloon faces.

Here sit the heavy balloon face women lifting crimson lobsters into their crimson faces, lobsters out of Sargossa sea bottoms.

Here sits a man cross-examining a woman, “Where were you last night? What do you do with all your money? Who’s buying your shoes now, anyhow?”

Marigold Gardens also had boxes filled with marigold plants, and Sandburg observed how the wind stirred these plants, as moths flitted around them.

Night moths fly and fix their feet in the leaves and eat and are seen by the eaters.

The jazz outfit sweats and the drums and the saxophones reach for the ears of the eaters.

The chorus brought from Broadway works at the fun and the slouch of their shoulders, the kick of their ankles, reach for the eyes of the eaters.

These girls from Kokomo and Peoria, these hungry girls, since they are paid-for, let us look on and listen, let us get their number.

Sandburg mused about why he kept returning to this place. Unlike the rest of the crowd—“the eaters” spending their “mazuma,” a slang word for money—Sandburg seemed content to watch this nocturnal tableau.

Why do I go again to the balloons on the wires, some thing for nothing, kin women of the half-moon, dream women?

And the half-moon swinging on the wind crossing the town—these two, the half-moon and the wind this will be about all, this will be about all.

Eaters, go to it; your mazuma pays for it all; it’s a knockout, a classy knockout—and payday always comes.

The moths in the marigolds will do for me, the half moon, the wishing wind and the little mile of balloon spots on wires—this will be about all, this will be about all.56

Ben Hecht gave his column about the Uptown flapper a curious title: “Nirvana.”

At the time, Americans were becoming more aware of Buddhism. Nirvana is a state in which the mind—enlightened as to the illusory nature of the self—transcends suffering and attains peace.

The word occasionally appeared in Chicago newspapers in the early 20th century. One Tribune article had defined nirvana as “a sort of superconsciousness so entirely above our usual brain states that words have not been found to compare the two.”57

The Illinois author Paul Carus, who introduced many American readers to Buddhism, offered this explanation in a 1902 book, which was published in Chicago: “When the fire of lust is gone out then Nirvana is gained. When the flames of hatred and illusion have become extinct then Nirvana is gained.”58

Was Hecht being ironic, suggesting that going out to a cabaret in Uptown was a path to enlightenment or annihilation of the self? Rosse’s illustration for this story in the 1922 book depicts the young flapper with the word “NIRVANA” spelled out vertically above her, resembling the sign on a theater or nightclub. The image implies that Nirvana might be the name of the cabaret.

Or perhaps Hecht was suggesting that this flapper—someone who seems far removed from any bodhisattva—had achieved a strange version of nirvana.

“Promoters of nightlife certainly tried to make their product seem hip,” Savage told me, when I asked him about Hecht’s “Nirvana” title. “And the very idea of Nirvana (being spiritually removed from space/time and blissfully fulfilled) synchs with the whole Jazz Age/dance/music/illicit booze vibe. You go out and seek Nirvana in excess of art and liquor (updated from ‘ecstasy’ in Greek tradition?) and find, as the last line of the story says, only loneliness.”59

At the end, Hecht’s story takes a turn toward sadness about the state of things during the Jazz Age: A feeling of loneliness in a crowded city. Ennui in the midst of all the hubbub.

A more academic writer, the Chicago sociologist Ernest R. Mowrer, may have sensed something similar when he tried to explain the reasons why traditional family structures were breaking down in Chicago—especially in neighborhoods like Uptown—during the 1920s. “The modern world presents itself as a spectacle in which the observer is never sufficiently participating,” he wrote. “The modern revolt and unrest are due to the contrast between the paucity of fulfillment of the wishes of the individual and the fullness, or apparent fullness, of life around him.”60

In the closing paragraphs of Ben Hecht’s “Nirvana,” the flapper delivers her own verdict on this Jazz Age scene, in blunt and simple words:

They came back from a dance and continued to sit. The din was still mounting. Entertainers fighting against the racket. Music fighting against the racket. Bored men and women finally achieving a bedlam and forgetting themselves in the artifice of confusion.

The newspaper man looking at his young friend saw her taking it in. There was something he had been trying to fathom about her during her breathless chattering. She talked, danced, whirled, laughed, let loose giggling cries. And yet her eyes, the part that the rouge pot or the bead stick couldn’t reach, seemed to grow deader and deader.

The jazz band let out the crash of a new melody. The voices of the crowd rose in an “ah-ah-ah.” Waiters were shoving fresh tables into the place, squeezing fresh arrivals around them.

The flapper had paused in her breathless rigmarole of Johns and memories. Leaning forward suddenly she cried into the newspaper man’s ear above the racket:

“Say this is a dumb place.”

The newspaper man smiled.

“Ain’t it, though?” she went on. There was a pause and then the breathless voice sighed. She spoke.

“Gee!”—with a laugh that still seemed breathless—“gee, but it’s lonely here!”61

An illustration from The Chicagoan, November 9, 1929.

A young female Uptown resident sounded a similar note when she was interviewed five years later by the Northside Sunday Citizen. The reporter called her an “attractive girl living just off Wilson and struggling for a living in the loop.” He was trying to understand why so many young women in Uptown spent their evenings going out with men.

She told him: “I feel rotten today, if you want to know. For two cents I’d go back home.”

“Why don’t you?”

“Well, it’s this way. You see, I’m from a small town up in Michigan and if I go back with the clothes I’ve got now, they would all have the laugh on me. Everybody knows me there and you know what a small town is. They’d all be glad to see me come back no better and probably worse than when I left.”

The reporter concluded: “I daresay if you directed that question to the average stray girl in this town you would receive about the same answer. Behind that forced smile, cheerful repartee, and affected sophistication, you will, nearly every time, find just a kid whose heart is aching to get back home and to forget all about that life of theirs that they wanted so much to live by themselves.”62

PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER

Footnotes

1 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 12, 1927.

2 Author’s analysis of 1920 U.S. Census Bureau pages for Chicago Ward 25, enumeration districts 1444 through 1481, Ancestry.com.

3 Ernest R. Mowrer, Family Disorganization: An Introduction to Sociological Analysis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1927), 114, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015012860659?urlappend=%3Bseq=140%3Bownerid=13510798884300720-142.

4 “Morals Probe of Wilson Ave: Sheridan a ‘Pick Up’ Paradise,” Northside Sunday Citizen, October 31, 1926, 1.

5 Analysis of 1920 census.

6 Meyer Levin, The Old Bunch (New York: Viking Press, 1937), 298, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b610327?urlappend=%3Bseq=318%3Bownerid=9007199272312151-362.

7 F. Dalton O’Sullivan, Crime Detection (Chicago: O’Sullivan Publishing House, 1928), 496–499, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951001572374d?urlappend=%3Bseq=512%3Bownerid=113532604-524.

8 “Morals Probe of Wilson Ave.”

9 Mowrer, Family Disorganization, 116–119.

10 “Morals Probe of Wilson Ave.”

11 Ben Hecht, “Around the Town: A Thousand and One Afternoons in Chicago: Nirvana,” Chicago Daily News, August 23, 1921, 26, reprinted in A Thousand and One Afternoons in Chicago, (Chicago: Covici-McGee, 1922), Gutenberg Project text, “Nirvana” chapter, https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/7988/pg7988.txt.

12 “Morals Probe of Wilson Ave.”

13 Balmer, That Royle Girl, 2.

14 Harold Charles Hoffsommer, “The Development of Secondary Centers Within Metropolitan Cities: ‘The Wilson Avenue District,’ Chicago” (master’s thesis, Northwestern University, May 19, 1923), 31.

15 Chicago, Vol. A (Sanborn-Perris Map Company, 1894), https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4104cm.g017901894A/?sp=1.

16 Tract Book 587B, 3, Cook County Clerk’s Office, Recordings Division.

17 “U.S. Ban Makes City Dry in Fact as Well as Name,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Nov. 1, 1919, 17.

18 Edwin Balmer, That Royle Girl (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1925), 2, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/osu.32435005378526.

19 Loren Miller, “You Can’t Sell Against That Competition,” System: The Magazine of Business, May 1921, 676.

20 Hoffsommer, “Wilson Avenue District,” 78–79.

21 Miller, “You Can’t Sell Against That Competition,” 676–677; Commission on Chicago Landmarks, Landmark Designation Report: Uptown Square District, October 6, 2016, 4, 7, 15.

22 Henry Justin Smith, preface, Hecht, 1001 Afternoons in Chicago, (3).

23 J.E. Lighter, ed. Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang, Volume 1: A–G (New York: Random House, 1994), 767.

24 “The Say a Flapper’s a Flipper From One Lap to Another,” Wichita (KS) Daily Eagle, August 21, 1921, 26.

25 Una, “What Is a Flapper?” letter to the editor, from Aquia, Virginia, August 18, 1922, (Fredericksburg, Virginia) Free Lance, August 22, 1922, 6.

26 “The Flapper” (Chicago: Exhibit Supply Company, 1923), https://www.loc.gov/item/2023638740/, https://www.loc.gov/item/2023638741/.

27 Making a Flapper Out of Mother” (Chicago: Exhibit Supply Company, 1923), https://www.loc.gov/item/2023638488/, https://www.loc.gov/item/2023638489/.

28 Hecht, 1001 Afternoons in Chicago, 127.

29 J.E. Lighter, ed., Random House Dictionary of American Slang, Volume II, H–O (New York: Random House, 1997), 299–301.

30 Miller, “You Can’t Sell Against That Competition,” 677, 678, 740, 744.

31 “Sheridan Plaza Hotel,” Wikipedia, accessed December 23, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sheridan_Plaza_Hotel.

32 “Chicago Local Notes,” Daily National Hotel Reporter, April 12, 1921, 4.

33 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, August 18, 1921.

34 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, September 18, 1921.

35 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, September 1, 1921.

36 “Uptown Chicago Interests Form Permanent Body,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 19, 1921.

37 “The Sheridan Plaza,” Daily National Hotel Reporter, May 27, 1922, 1.

38 “Uptown United Chicago,” Yelp, accessed December 25, 2023, https://www.yelp.com/biz/uptown-united-chicago.

39 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, April 6, 1924, part 11, 9.

40 “Parade to Feature Pageant,” Chicago Daily News, August 13, 1925, 14.

41 Hoffsommer, “Wilson Avenue District,” 17–19.

42 Hoffsommer, “Wilson Avenue District,” 77.

43 Journal of the Proceedings of the City Council of the City of Chicago, Illinois, vol. 98, June 18, 1924, 3442. https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofcit98chic/page/3442/mode/2up.

44 “Chicago Community Champions Stirred,” Chicago Daily News, August 29, 1925, 14.

45 “More Letters Sing Community Praise,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 30, 1925, part 7, 4.

46 “Uptown Chicago Projects $150,000 Campaign of Ads,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 8, 1927, 5.

47 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 12, 1927, 48.

48 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 5, 1927, 9.

49 Ernest W. Burgess and Charles Newcomb, Census Data of the City of Chicago, 1920 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1931), 608, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951p01104667o?urlappend=%3Bseq=628%3Bownerid=114364795-786.

50 Louis Wirth and Margaret Furez, eds., Local Community Fact Book, 1938 (Chicago: Chicago Recreation Commission, 1938), 21, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924014569606?urlappend=%3Bseq=21%3Bownerid=27021597768275930-25.

51 “Mapping the Young Metropolis: The Chicago School of Sociology, 1915-1940: The Local Community,” University of Chicago Library, 2015, accessed March 9, 2024, https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/collex/exhibits/mapping-young-metropolis/local-community/.

52 Amanda Seligman, “Community Areas,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/319.html.

53 “More Uptown History” (letters to the editor by Martin C. Tangora and LeRoy Blommaert, with response by Harold Henderson), Chicago Reader, May 10, 2007, https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/more-uptown-history/Content?oid=924945.

54 Bill Savage, introduction, Ben Hecht, 1001 Afternoons in Chicago, (80).

55 Edwin Balmer, That Royle Girl, 5, 7, 8, 18, 91.

56 Carl Sandburg, “Balloon Faces,” Smoke and Steel (New York, Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1920), 224–225, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015002757766?urlappend=%3Bseq=240%3Bownerid=13510798888017166-254.

57 “Your Corner…Fadette,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 7, 1907, part 6, 2.

58 Paul Carus, Nirvâna: A Story of Buddhist Psychology (Chicago: Open Court Publishing, 1902), 15–17, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/ia.ark:/13960/t7mp53h5g?urlappend=%3Bseq=21.

59 Bill Savage, email to author, November 27, 2023.

60 Mowrer, Family Disorganization, 155.

61 Hecht, “Nirvana.”

62 “Morals Probe of Wilson Ave.”