An Addendum to Chapter 1

of The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— CHAPTER 1 / TABLE OF CONTENTS / CHAPTER 2—>

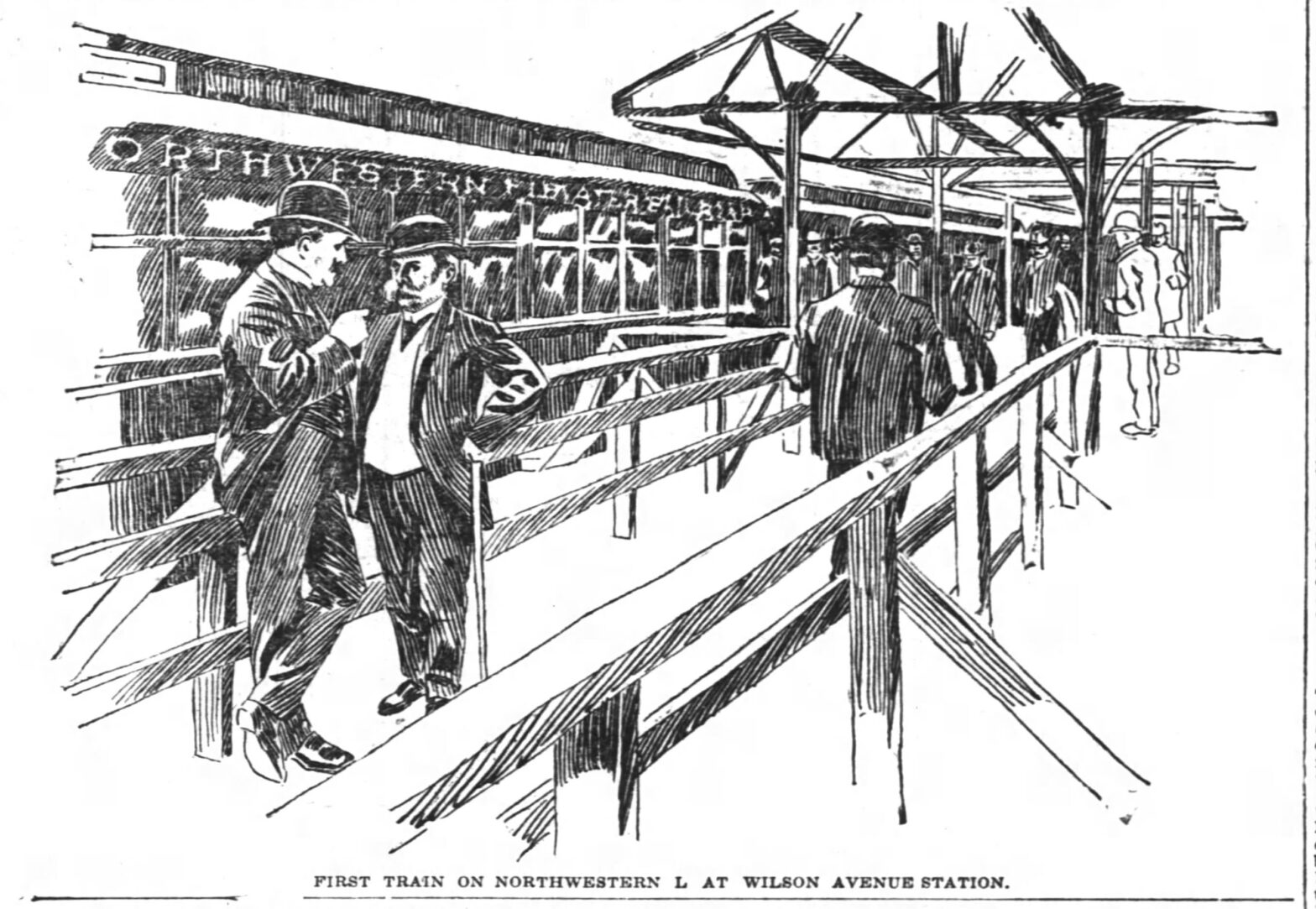

May 31, 1900, was one of the most momentous days in the development of Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood. This was when the first elevated trains arrived at Wilson Avenue, traveling from the Loop to the north end of the Northwestern Elevated Railroad’s new tracks.

These speedy electric trains made the area around Wilson Avenue far more accessible. The “L” (or if you prefer, “the el”) sparked a boom in local population growth and the rise of a business and entertainment district. Taking a route still used today by the CTA’s Red Line and Purple Line, the trains could make the 6.5-mile trip from downtown to Wilson in 29 minutes, or as fast as 17 minutes when they ran express.

Charles Tyson Yerkes, the tycoon who controlled the Northwestern Elevated, was a controversial character, accused of enriching himself at the expense of everyday Chicagoans and bribing public officials to build his rail systems, as I detailed in a 2010 Chicago Reader cover story. John Franch’s 2008 biography of Yerkes is titled Robber Baron. But on May 31, 1900, Yerkes was applauded like a conquering hero. A crowd of VIPs cheered loudly when he spoke on the Wilson Avenue platform.

An excerpt from the Inter Ocean’s reporting on the arrival of the first “L” trains at Wilson is below, followed by a later article describing (in rather humorous detail) how residents of Sheridan Park and Evanston reacted to the hordes of passengers.

New “L” Is Running

Inter Ocean, June 1, 1900

The Northwestern Elevated railroad was formally opened for traffic at noon yesterday. Officials and invited guests to the number of 500 filled the first and second trains. …

The first special train entered the loop at Fifth avenue and Lake street just as the hands of the clock on the Northwestern Railroad depot pointed to the figure 12. The train turned east on Lake street and followed the route taken by the Lake street elevated trains around the loop. Stops were made at all stations, and invited guests were taken on board at each of them. The train was decorated with bunting and flags and moved from station to station without the least delay. People on the streets along the route were attracted by the unusual noise of cheering and good fellowship which marked the outing of bankers, capitalists, business men and officials, and they in turned cheered the train.

When Fifth avenue and Randolph street was reached and the circuit of the loop was completed, President [Delancey H.] Louderback gave the signal for the throwing of the switch which would allow the train to pass upon the new tracks.

“We are running our trains left-handed,” said Mr. Louderback, in explaining why north-bound trains took the west track and the south-bound trains the east track. “It saves us crossing over the tracks to get on the loop.” …

On reaching the bridge across the river the guests were saluted by the blowing of whistles, the ringing of bells, and loud cheers. A man of tug captains, anticipating the opening, and wishing to give the road a good “send off,” had anchored on either side of the Wells street bridge. “Here she comes!” shouted a boy from a point of vantage, and then the tug whistles broke float. Everything afloat in the river that had steam and a whistle joined in the noise. … all along the route thousands of people were waiting to see the first train, and express their appreciation of the completion of the enterprise.

At Wilson avenue the guests were conducted to the handsome depot of the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul road, where a luncheon had been prepared. …

[Louderback said,] “It is one of the best elevated roads in the world. At the time we tried to promote this enterprise the elevated railroads of Chicago were bankrupt and capitalists hesitated about putting their money into the scheme. There was, however, a man who had faith in Chicago, in elevated railroads, and in himself, and he had the financial ability to draw other capitalists to him. I speak of Charles T. Yerkes, who is responsible for the completion of this road.”

Mr. Yerkes was loudly cheered when he mounted the platform, and it was some time before he could be heard.

“You all know the time when we started this structure,” he said. “You will remember that it was a very difficult undertaking. Elevated roads were not then in the fashion. People did not care to put their money into an enterprise of this character. We were finally compelled to stop work because of financial troubles. After much persuasion we succeeded in inducing New York capitalists to furnish the money. We painted the picture very attractively for them. We said many people were building fine residences along the north shore in the believe that they would be enabled to get rapid transportation to the city, and that we were unable to accommodate them unless we could get aid. A great deal of credit is due to those who came in and helped us at the eleventh hour.

“It is a good structure; there is none better, and it runs through the best section of Chicago. There are many here today who are astonished to see so beautiful a country around them. The country needs no praise from me. It speaks for itself. The people of Chicago are divided into three communities, and residents of one district seldom get far enough away from their homes to visit the others. We do not doubt that many people living on the South and West Sides will now give up their homes and come over here to ride on the Northwestern elevated. The property-owners along the line have been patient, and for this we thank them. Their dreams of rapid transit are now a reality.”

“Beer Gives Them Fits”

Inter Ocean, June 17, 1900

Sheridan Park’s Protective association and the Evanston Anti-Picnic society are overworked. They never were so overworked in their lives. They are “up against it” in the very worst way.

For two Sundays past, since the opening of the new Northwestern Elevated railroad, 75,000 common, ordinary picknickers, with baskets on their arms, joy in the hearts, and $5,000 worth of peanuts in paper bags, have swooped down on the North Shore lawns like jaunty grasshoppers. Some have even carried bottles of beer, and the innocent youth and dignified age of Evanston are getting to know “ales, wines, and liquors of all sorts” on sight.

“Terrible that the streets of the only Athens in Illinois should be desecrated by the sight of Pilsener,” began Mrs. Carse as she met Mrs. Helen M. Barker.

“Pilsener!” ejaculated the treasurer of the W.C.T.U. “My dear, it was Schorr Brau!”

“No, no, friends,” interposed Miss Lucy Page Gaston in her gentle way, “they were all American brands!”

And so the discussion goes on, and Evanston is learning things. The classic town which less than six months ago put a ban on root beer, and within the week thrust President Henry Wade Rogers into outer darkness, is being invaded by the common, ordinary feet of plain Chicago people who eat cookies and peanuts and fried chicken and go picnicking on Sunday. It is all owing to the Northwestern Elevated railroad, which Evanstonians and Sheridan Parkers have been thirsting for. On the first Sunday after the opening of the new road 75,000 passengers were carried out to the end of the line at Wilson avenue. Some of them wandered about the beautiful park, the broad boulevards, and the artistic lawns. They saw sylvan sports ‘to beat the band,’ as one of the conductors puts it, and they plunged down on those sylvan spots and spread their luncheons and had a good time.

They saw snowballs, and geraniums, and lilacs, and roses all growing in profusion, and no fences up. Everybody went back with a bouquet and a pleasant ta-ta for their entertainers. Sheridan Parkers sat on the broad porches of their colonial homes and laid plans for using the fire hose and the police department to suppress picknickers. A lot of the 75,000 people who rode out to Wilson avenue looked over the suburb and then took a trolley car at that point for Evanston.

Evanstonians heard of the invasion before it started. The news was broken to the suburb by Volney Foster. Mr. Foster was walking down Davis street in the cool of the morning on his way to Sunday school. He was thinking that a walk down Davis street was equal in quiet and dignified repose to a saunter along the subdued aisles of Westminster abbey. Presently the trolley cars began to arrive with people on them—hundreds of people with baskets on their arms. Mr. Foster is democratic. He is a man of the people, as everybody in Evanston knows, but he is loyal to Evanston. He feels about Evanston as Boston people feel about Boston. Walking on the street in Evanston on Sunday, except to and from church, in a decorous way, is bad form. Even the Evanston police refrain from carrying clubs on Sunday.

Occasionally strangers venture forth in search of blind pigs. That exertion looks so much like work that many of the best people consider it a breach of Sunday etiquette.

So Mr. Foster communicated with William Deering and Judge Wing, Mr. Dawes, and Charles H. Aldrich, and other persons who have a habit of living in Evanston. By that time Evanston lawns were transformed into an animated scene resembling camp meeting at Asbury Park, with here and there a dash of Coney island. Nearly everybody had a bouquet, and there was no doubt about it that the visitors appreciated nice scenery.

“Set the fountains going on the lawns, Judge,” called Mr. Foster as he sprinted across the town hall to ring the fire alarm.

“Bring on the fire hose,” commanded Mr. Deering, “what ho, there, wardens; let the portcullis fall and set a strong guard about the peanut stands.”

“Let every man do his duty and protect his own vine and fig tree and lettuce beds and things,” shouted Professor Cumnock, who leads Evanston youth in the paths of elocution.

And so for an hour excitement reigned. The picnickers stood their ground, resolved, if need be, to die by their pop bottles and their crackerjack boxes. Then a truce was proposed. Judge Wing and Mr. Foster conferred with a leader of the picknickers, a Chicago man who had some stuff in bottles. He poured some of the stuff into glasses, and Judge Wing believed it to be root beer. Mr. Foster thought it was sweet cider. They so understood it, and understanding it so they drank.

“That is the best root beer I ever sampled,” said Judge Wing to Mr. Foster.

“It’s sweet cider, Judge, but it’s all right,” said Mr. Foster. “The best I ever tasted.” And then Mr. Foster reflected a minute and remarked, “Judge, this picnic is not an invasion. It’s expansion.”

“Civilization has overtaken us,” responded the Judge solemnly.

The two then withdrew and called off the fire hose brigade.

Something like the same thing took place in Sheridan Park. On the first Sunday every Sheridan Parker mounted guard on the front steps to warn excursionists off the flower beds, while he stationed his groom or his gardener at the back with a garden hose in case worst come to worst.

“May I pick some flowers?” shouted a city visitor.

“No; get out!”

“Say, is this a park or isn’t it?”

“It’s a park, but—”

“Well, then, get out yourself,” and the hardy lovers of nature then strode in and made themselves at home.

The second Sunday after the opening of the new Northwestern L, however, what promised to be a general revolt against picnickers subsided. Visitors walked along more decorously, warned by big red and black signs against trespassing on private property, and by today complains from householders will have been reduced to a minimum.

In Sheridan Park, as in Evanston, Argyle Park, Edgewater, Rogers Park, and other suburbs made easily accessible by the new road, all the lawns are open. Fences are unknown, and the suburbs have the appearance of beautiful and well-kept public grounds. Thousands of people in Chicago up to two weeks ago had very little connection of the territory which has been settled up on the Northwest Side in the last ten years. The Northwestern elevated train runs through the heart of this district, and from Chicago avenue to the end of the line there is spread out a panorama unequaled in any of the rides about Chicago. Starting from Madison street it takes twenty-nine minutes now to get to the end of the line, at Wilson avenue, in Sheridan Park. Within a few days, when the express trains are put on, this will be shortened to seventeen minutes. The entire distance is six and one-half miles, and the area served by the road might be calculated to extend one-half mile on either side, exclusive of the cross-town lines which act as feeders to it. The territory has every distinct characteristics, and owing to the inadequate transportation hitherto it is little known by the average Chicagoan. From the down-town district up to Fullerton avenue the roads through, first, dense, active, stirring localities, like Lake, South Water, Franklin, Kinzie streets, Chicago avenue, and son. Then the semi-residence and residence portions of the route begin.

One of the surest ways to judge of a city district is by the back doors and back yards of the houses. Unlike every other elevated road in the city, the Northwestern runs through an area of grassy back yards, flower beds, little house gardens with bed of bright green lettuce, and alleys kept clean. Everything bespeaks industry and thrift and wholesome self-respect. Glancing out of the window one gets the impression that a great many people along the route own their homes. Away out over the roofs of the houses is a splendid view of the city for miles and miles to the west. Looking down, broad streets, shaded with trees in full foliage, flash by and as far as the eye can reach a brilliant blue sky bends over a soft haze of smoke from the factory chimneys of the whole Northwest Side. To the east the scene is even busier, and every thoroughfare ends its green arch in the lake that twinkles through the trees. At Addison street the territory begins to get more open and on either side are homes with big lawns, with here and there vacant lots like parks set in trees.

“No wonder picnickers flock to Sheridan Park,” said a Chicago business man as the train neared Wilson avenue station. “I call a view like that two minutes pretty cheap at 5 cents.”

Continue to Chapter 2: Piecing Together the Green Mill Puzzle