Chapter 16 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

As 1917 began, Tom Chamales was arguing with his landlords, Catherine and Charles Hoffman, about changes he’d made at Green Mill Gardens. He’d apparently removed some stairways between the building’s first and second floors. Which stairs did he remove and why? That’s unknown. But this work prompted the Hoffmans to challenge his right to make “changes, alterations, additions and improvements” without their permission.

And so, Chamales proposed an amendment to his lease. He tried to get the Hoffmans to sign a document approving all of the changes he’d made—and clearing the way for even more alterations—while confirming that the lease was still in effect.

Chamales also agreed that he wouldn’t renew the sublease for John F. Butterly’s saloon at 4812 North Broadway, in the building’s north wing. Was the presence of Butterly’s saloon a source of tension with the Hoffmans? (And did this have anything to do with the shooting death of a bartender for Butterly on December 26, 1916, just a month before Chamales proposed this lease amendment?)

Did the Hoffmans agree to this new deal? That isn’t clear. But when Chamales finally submitted this document to the Cook County recorder of deeds—four years after the fact—it wasn’t signed by the Hoffmans. And it hadn’t been notarized in 1917.1

A very jazzy year

After trickling into the American vocabulary over the previous couple of years, the word jazz burst into common use in 1917. On January 19, an advertisement by the Boston Store, a department store in Chicago’s Loop, defined jazz as “the droll saxophone music has been so successfully imitated by the piano.” The ad was promoting player piano rolls for the songs “Allah’s Holiday,” “Bachelor Days,” “Florida Blues,” “Chicken Walk,” and “If You Ever Get Lonely.”2

What exactly was jazz? The Youngstown Telegram offered this description, which was reprinted in the Rock Island Argus:

Usually, the jazz band is made of a pianist who can jump up and down while he is playing; a saxophone player who can stand on his ear; a drummer whose right hand never knows what his left hand is doing; a banjo plunker; and a violinist who can dance the bearcat. … While the music is throbbing and the dancers are swaying, they get into action until the air is full of flying feet, grabbing hands, drummers’ gimcracks and delighted exclamations. The exclamations are usually such as “Attaboy!” “Oh, doctor!” “Swing me dizzy!” and “Oh, Babe!”3

Robert W. Stevens, the University of Chicago’s musical director, came to the defense of jazz, noting that Wagner, Brahms, and Liszt had all composed music with similarities to jazz.

Robert W. Stevens, the University of Chicago’s musical director, came to the defense of jazz, noting that Wagner, Brahms, and Liszt had all composed music with similarities to jazz.

“As for Brahms, his ‘Hungarian Dance’ in F sharp minor is in principle the same thing that we condemn in the ragtime of a jazz band,” he said, also pointing to Liszt’s Second Rhapsody as a composition that included “some more nice ragtime.”4

The Geo. P. Bent Company, 214 South Wabash Avenue, enticed shoppers with an advertising asking: “Ever Hear a JAZZZ Band? Come In and Hear These Jazz Band records.”5

The Chicago Daily News wrote about a woman who borrowed someone’s record of a “Syncopated Jazz Band Rag” and played it until it was worn thin, breaking into seven pieces.6

And dance instructors began offering lessons on how to dance to jazz music, as the Tribune reported: “The Super-Jazz has been newly created, devised, invented, constructed, or whatyoumaycall it, by Arthur L. Kretlow of 637 Webster avenue. Prof. Kretlow will present the Super-Jazz for the Chicago Association of Dancing Masters’ Normal school.”7

It became trendy to do jazzy versions of old songs. For example, the Steger Talking Machine Shop at Wabash and Jackson advertised Arthur Collins’s record “Get a Jazz Band to Jazz the Yankee Doodle Tune.”8

But the Daily News jokingly complained that this fad could go too far: “Putting jazz in the wedding march may be all right, but a neighbor of ours is trying to jazz ‘Hark, from the Tomb’ and the ‘Dead March.’ Suggests that the hearse chauffeur might be arrested for exceeding the speed limit.”9

As that comment suggests, fast tempos were a key part of early jazz music.

Newspapers sometimes described jazz as a noisy, tuneless racket, questioning how anyone could enjoy it.

“Our notion of how jazz was invented is that a pifficated musician attempted to play his Chinese laundry ticket by mistake,” the Daily News commented, illustrating the joke with a cartoon.10

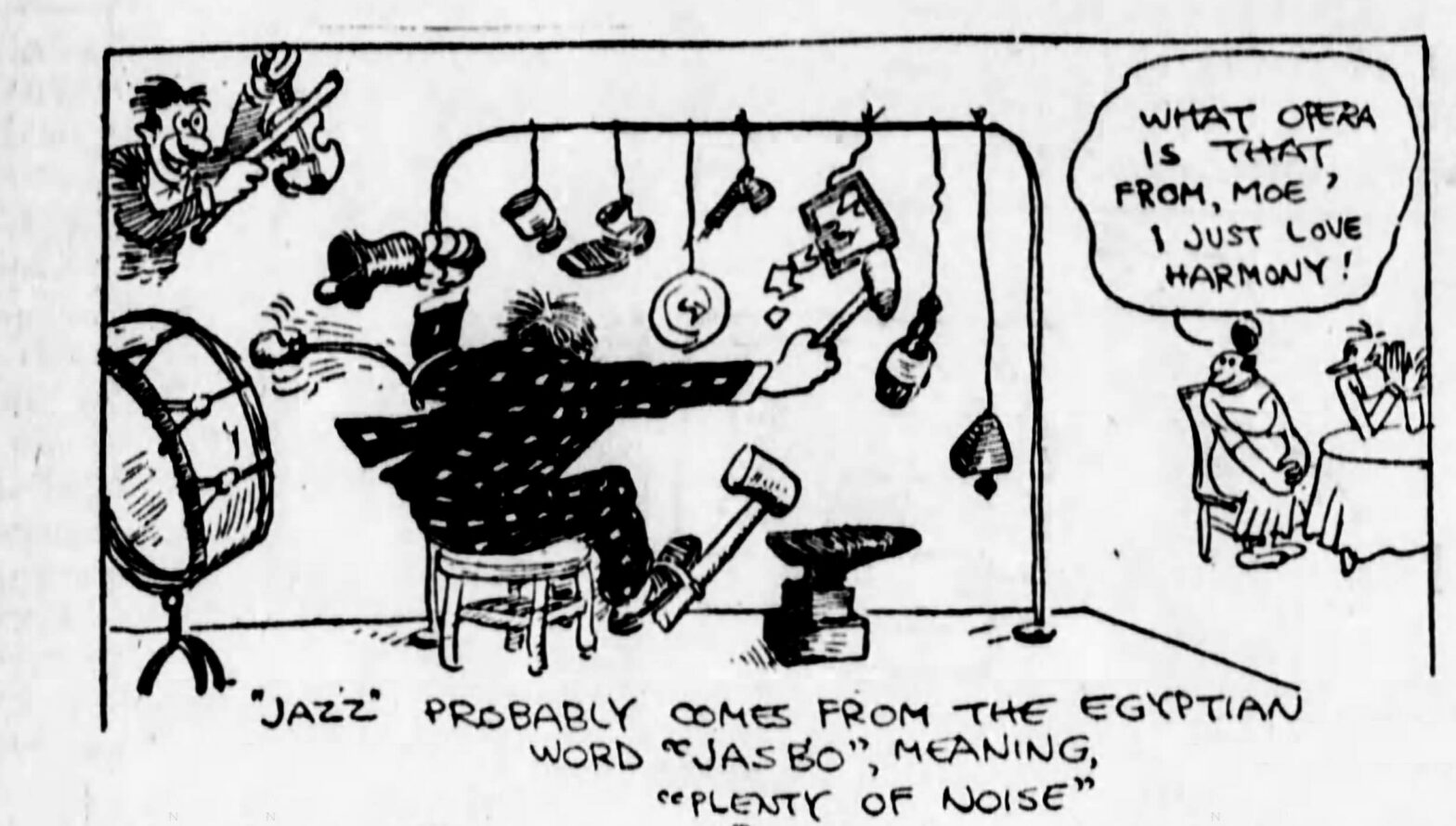

A syndicated comic strip by Rube Goldberg, which appeared in the Daily News on September 21, 1917, included a humorous stab at the word’s etymology:

“‘Jazz’ probably comes from the Egyptian word “jasbo,” meaning “plenty of noise,” a caption said.

Alluding to men who were headed to Europe to fight in trenches, the comic also said, “The man whose ears are hardened to jazz music needn’t worry about losing sleep in the trenches.”

The comic strip also showed a man looking at car making noises: blurp, tap, knock, thump, click. “The jazz band leader is always on the lookout for new noises,” it explained. This bandleader exclaimed: “Every note is perfect—I must have my drummer play it on the tin can with a broken bottle accompaniment.”11

Writing in the Daily News, critic John V.A. Weaver Jr. argued that jazz was “the essence” of African American music. Although he seemed to be expressing some appreciation for Black jazz—while criticizing the versions of the music performed by white vaudeville artists—Weaver revealed his notions about what “the essence” of Black people was:

Fundamentally, perhaps, [jazz] is the expression of his savagery; the hysteria, the madness that underlies all his life; the loudness of his laughter, the brutality of his rage, the bestiality of his lust; the plaintiveness and childishness of his sorry. Technically, it is the tom-tom of his meter, the sob of his cello, the wail of his violin, the moan of his trombone, the dying-cur-in-its-agony of his clarinet. It is the sinister, the elemental, the “blue” of the African soul. If realism be art, the jazz of the negro is art of the first water.

The white man has seized upon this quality and made it his own. He has taken it to his vilest bordellos; he has exploited it in the temple of the hyper-moron—vaudeville; it is “the rage.”12

The Great War and Chicago’s mayor

On April 2, 1917, president Woodrow Wilson spoke at a joint session of Congress, asking for a declaration of war against Germany. Congress approved the measure four days later.13 The United States was now joining the war that had been raging across the European continent for nearly three years. Known at the time as the Great War, it would go down in the history books as World War I.

Chicago’s Republican mayor, William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson, had spoken out earlier against U.S. involvement in the war, and he didn’t change his tune now, even while many Americans rallied around the U.S. “doughboys” going off to fight in Europe.

Explaining his reasons for opposing war against Germany, Thompson noted, “Chicago is the sixth-largest German city in the world.” On another occasion that spring, he remarked: “This war is a needless sacrifice of the best blood of the nation on foreign battlefields.”

Thompson faced withering criticism, from many people in Chicago as well as others across the country. “Is Chicago for the United States or for Germany?” a newspaper in Philadelphia asked. “Why hasn’t Thompson been arrested as mayor of a German city, openly sympathizing with the nation with which we are at war?”

Critics started calling Chicago’s mayor “Kaiser Bill,” “Wilhelm der Grosse,” and “Burgomaster Bill.” Aldermen said he was “a low-down double-crosser,” “a disgrace to the city,” and “the laughingstock of America.”

That fall, the Society of the Veterans of Foreign Wars hanged the mayor in effigy on Chicago’s lakefront while thousands of people cheered and sang: “Hang Big Bill! Hang Kaiser Bill!”

But Thompson insisted: “It was Europe’s fight and not ours. I claim the right to differ with other people and I accord other people the same privilege of differing with me, and I do not propose to be influenced by threats of personal violence or of political annihilation.”14

As the United States started sending American soldiers to fight in Europe, the campaign against alcohol was ratcheting up. It became a crime to sell alcohol to soldiers. Liquor sales were forbidden within five miles of any naval base.15 And for Americans who hoped to preserve their right to drink beer, it didn’t help that most of the country’s brewers were of German heritage.16

“We have German enemies across the water,” a dry politician in Milwaukee remarked. “We have German enemies in this country too. And the worst of all our German enemies, the most treacherous, the most menacing, are Pabst, Schlitz, Blatz, and Miller.” 17

As German Americans faced questions about their loyalty, one of Green Mill Gardens’ biggest competitors, Bismarck Gardens, changed its very German-sounding name. It was rechristened as Marigold Garden.18 The Tribune commented: “Bismarck garden with its traditions and its Teutonic odor has become passe, it is said, and a more lilting, joyous, and pro-American name withal will reign in its stead.”19

In a case of bad timing, the South Side’s Midway Gardens had switched to a more Germanic name in 1916, when Schoenhofen Brewing Company acquired the bankrupt venue and renamed it after the company’s most popular beer, Edelweiss.20

Schoenhofen, which made 1.2 million barrels a year in a brewery at Canalport Avenue and 18th Street in the city’s Pilsen neighborhood, fell under suspicion in 1917, as federal agents heard reports from confidential sources that the company was largely “controlled by alien enemy interests.”

These rumors focused on Count Oscar Bopp von Oberstadt, a German immigrant who’d married a daughter of the brewery’s founder. “Advocating US neutrality and peace, Bopp showed obvious sympathies to the Kaiser,” historian Paul Durica wrote. But when federal authorities eventually raided Bopp’s home near suburban McHenry, they didn’t find anything nefarious.

“In looking over the personal effects of the Count, the only incriminating thing the Agent found was a large photograph of the Kaiser,” an agent for the Bureau of Investigation (the FBI’s forerunner) reported.

Or as Durica put it: “The marshals did not locate the suspected ‘powerful wire-less apparatus,’ but the government nevertheless seized the brewery. The Schoenhofen family spent the better part of a decade seeking restitution.”21

The shows at Green Mill Gardens

In May 1917, a month after Congress declared war against Germany, Green Mill Gardens staged The Spirit of 76, a show built around the patriotic song “It’s Time for Every Boy to Be a Soldier.”22

That October, Green Mill Gardens hosted 102 draftees from the U.S. Army’s 55th Division, serving breakfast to the soldiers and their families while a revue of entertainers performed. Afterward, the men headed off to Camp Grant in Rockford, preparing to make their way to Europe to fight in the Great War.23

In between those war-themed events, 1917 was a busy year at Green Mill Gardens, including a return engagement by “the stellar attraction,”24 Patricola—who was now performing with a chorus of 18 girls in a show called the Book of Smiles Revue.25 Other performers at the venue in 1917 included:

— The Gorman Brothers,26 who were known as “the boys with a thousand songs” and “the singing reporters.” These Chicagoans, Billy and Eddie Gorman, wrote songs based on the news events of the day, often visiting newsrooms in the cities where they were touring. “As the news copy comes from the telegraph operators, the vaudevillians cast their respective eagle eyes over it and select five or six items for jingling purposes,” according to one report.27

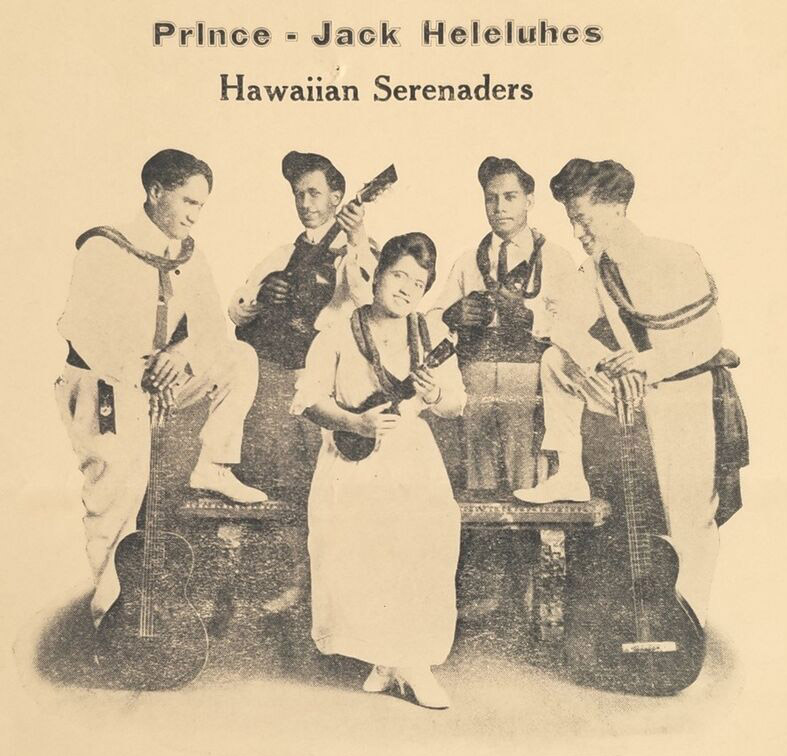

— Prince Jack Heleluhe, a member of Hawaii’s nobility who played steel guitar and sang baritone,28 performed with his Hawaiian Serenaders.29

— Giuseppe Sirignano conducted the 50 musicians in an orchestra called Banda Roma.30

— A pair of actors named Morrissey and Woodward did the donkey pantomime from former Chicago author L. Frank Baum’s latest play, The Tik-Tok Man of Oz.31

— Mlle. Marion and Martinez Randall performed an equestrian-inspired dance they called “The Highland Gallop.” The New York Clipper explained: “She is the steed in harness, while he ‘holds the reins.’”32

Ralph Dunbar’s Tennessee Ten. Howard University, Digital Howard, Harry Bowman Black Vaudeville Collection.

Nearly all of the entertainers who performed at Green Mill Gardens in this era were white. But Ralph Dunbar’s Tennessee Ten, a group of Black entertainers—who included one white singer for at least a time33—performed there for a few weeks in July and August 1917, advertised as “A RIOT OF FUN.”34

The Chicago Defender called them “one of the biggest hits in vaudeville” and “a group of the Race’s best entertainers and musicians.”35

It was the sort of show that this Black newspaper viewed as a celebration of Black culture and talent. But like much of that era’s entertainment, it may well have included elements that today’s audiences would see as demeaning stereotypes.

Earlier that year, the Flint Journal had praised the Tennessee Ten’s “wild, weird, and woozy jazz music.” Typical for that time, the Michigan newspaper used some racially offensive language even as it offered acclaim:

Soft shoe dancing that embraces many kinds of variety shuffles and gymnastic singing of all brands of darkey vocalization is indulged in to the huge delight of the audience. There is antiquated Uncle Jasper who spins chuckly quips and there are two brunette belles who dance, sing and cavort with a world of pep and grace. The scenes are laid in the good old plantation days, with the Tennessee Ten offering a replica of plantation pastimes that develops into a riot of applause. And at last there is the “Jazz” band as the top plum in a pudding of real vaudeville relish.36

Moulin Rouge, the future Rainbo

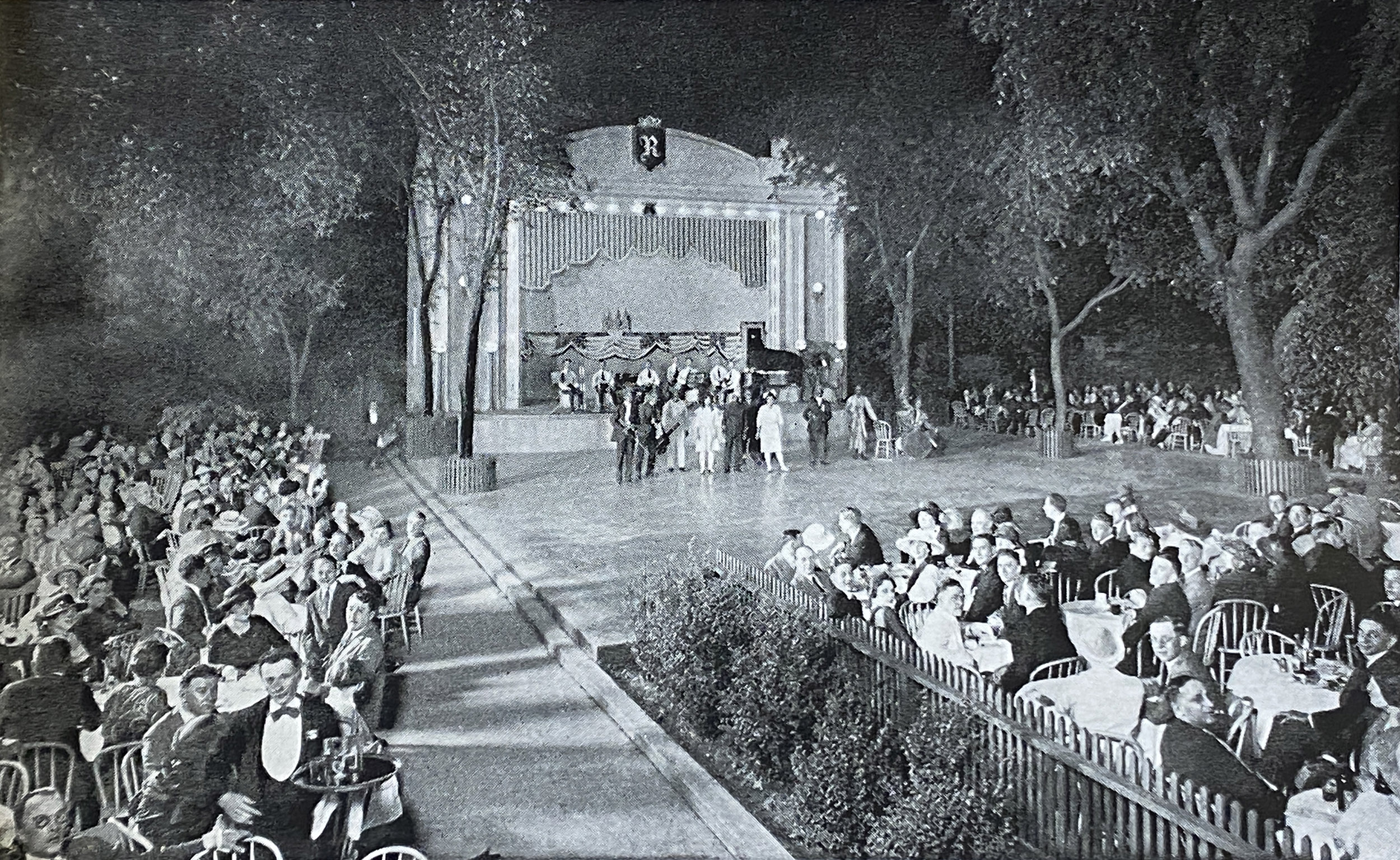

Green Mill Gardens had a new competitor that summer. On May 30, 1917, the Moulin Rouge opened roughly five blocks away, on Clark Street just north of Lawrence Avenue. Located across the street from the entrance to St. Boniface Cemetery, it was at the same spot where a cemetery saloon had operated for years, but now it was a “Palatial”37 entertainment complex of a much larger scale.

“Elaborate preparations have been made for the accommodation of some 2,700 persons,” the Daily News reported.

While the name of Green Mill Gardens hinted at a connection to the Moulin Rouge in Paris, this new venue didn’t bother with hints. It claimed to be “a replica of the noted Paris resort,” built at a cost of $300,000.38 And the staff included Albert Bouche, a 36-year-old Italian immigrant39 who was said to be a former chef at the Moulin Rouge in Paris. He would “give his personal supervision to the cuisine.”40

Chicago’s Moulin Rouge had three dance floors—indoors and outdoors—with colored electric fountains scattered amid the tables in the Café la Marquise and the Galleria Umberto.41

The Moulin Rouge held open-air concerts every evening, featuring classical musicians and singers, with Luigi D’Urbano conducting his band of 40 musicians.42

“D’Urbano affects a most remarkable series of absurd mannerisms, shaking his massive head with its great shock of hair,” the Rockford Republic had observed, “waving his arms and throwing his body this way and that as though by the very force of example to throw his men into a frenzy of tuneful excitement, then again standing almost on tip-toe and making the daintiest movements with his baton as a painter putting the last touches to a masterpiece.”43

The Moulin Rouge’s president, John M. Kantor, had connections at City Hall. He’d been a stump speaker for Mayor Thompson, before serving in the Thompson administration as a real estate expert for the city’s Board of Local Improvements and the chief investigator in the city attorney’s office.44 But Moulin Rouge Garden’s corporation papers show that the venue’s actual owner—who owned all but three of the company’s 247 shares—was its architect and builder, Niels Buck.45

A year after opening, the Moulin Rouge went through bankruptcy46 and reopened as Rainbo Garden.

The new owner was a 44-year-old German immigrant named Fred Mann.47 He chose the Rainbo name as a tribute to the 42nd Infantry Division,48 which had been mobilized in August 1917, pulling together National Guard units from across the country as a way of sending soldiers quickly to Europe. Major Douglas MacArthur said the division would stretch across the United States “like a rainbow,” and so, it came to be known as “The Rainbow Division.”49 Mann’s son was serving in the division.50 It’s a mystery why Mann chose to spell “Rainbo” without a “w.”

Undated postcard photos of Rainbo Garden. Curt Teich Postcard Archives Collection, Newberry Library.

Green Mill Gardens heist

In the early morning hours of July 30, 1917, several men climbed over a wall into Green Mill Gardens. On the veranda, they encountered Tom Chamales’s cousin Louis Chamales, who was working as the night watchman.

Louis struggled with the intruders, wresting a revolver from one of them before he was knocked unconscious with a chisel. Two porters, who were working elsewhere in the building, heard the noise and rushed to the scene. The intruders overpowered them, leaving them bound and gagged.

The robbers went to the building’s office, which had two safes in it. They drilled a hole in the larger safe, placed a charge of nitroglycerin inside, and then covered the safe with wet towels to deaden the explosion. The blast tore loose the safe’s doors. And then these “yeggmen” used a hammer to get into the safe’s inner compartments. They took $2,500 to $5,000 in cash and jewelry valued at $1,700, which customers had given to the venue for safekeeping.51

Commenting in Hotel World magazine about the robbery, Tom Chamales said, “It’s an ill wind that blows nobody good.” But he was relieved that the robbers had failed to get another $5,000, which was stored inside a small safe hidden by a pile of dirty linen.52

Police arrested several men as suspects, but most of them were freed when Louis Chamales was unable to identify them in court. The only suspect who was charged was William Rooney.53

The U.S. government’s Bureau of Investigation included a headline about this robbery in a file of newspaper clippings. Curiously, someone at the agency wrote this note beneath the headline:

“If Billy Sunday does not clean up crime in Chicago, he will clean up a bunch of money. Burglary and evangelizing are commercial pursuits.”54

Cabarets and jazz under attack

In 1917, Chicago’s puritanical reformers continued complaining about the supposed evils of cabarets—and as jazz grew in popularity, the music was often the target of criticism. The Chicago Daily News summed up the attacks on cabarets and jazz with a bit of editorial poetry:

The cabaret it cannot stay,

The jazz band we must lose,

The burlesque show will have to go—

All minions of King Booze!55

One night in October 1917, police officers descended on cabarets and arrested around 200 men and women on “morals” charges.

“Give us 500 more policeman and police women, or divorce jazz music, liquor, and dancing,” first deputy Wesley H. Westbrook remarked. “The combination of the three is a menace. As far as music and eating are concerned, there is no cause for protest. But the people who go to the jazz band cabaret do not go there to eat. Jazz band music is no more music than whisky is a thirst quencher. It is a syncopated form of noise that appeals to the passions. With that kind of music, what kind of dancing can you expect?”56

Municipal judge Joseph Z. Uhlir, who presided over a courtroom known as the “morals court,” offered this description of Chicago’s cabarets:

“Some cabarets are rather vicious. Evidence presented in court shows that women openly solicit men; young girls frequent dance parlors and cabarets and are sold liquor; minors become intoxicated; the number of married women figuring in morals court cases is increasing; and the host and hostess evil is growing more dangerous.

“The cabarets in the heart of the city have developed extremely bad conditions. The dancing rooms in the Loop hotels, and the ‘pink teas’ are supplying a continuous supply of victims to the morals court. The apparently respectable Loop places are more dangerous than the smaller outlying cabarets, in my opinion. Parents would not allow their daughters to go to the latter, while they think the former respectable.

“In one of the Loop places recently a boy and girl were allowed to become intoxicated on champagne. Girls who give their age as 18, but look no more than 16, are brought into court daily. They tell the same story—cabarets, intoxication, hotel raid. Married women are brought in. Many of them left babies at home to attend ‘pink teas,’ where they met strange men. I am told in some Loop hotel dance parlors women drink, gamble and smoke. Before any progress can be made the Loop parlors masquerading as respectable must be curbed. Highballs and jazz dance music are behind a great percentage of the cases before me.”

One of the cabarets described by authorities as a trouble spot was the Lafayette Cafe, which was at 4836 North Broadway, in the same block as Green Mill Gardens.

Police superintendent Herman Schuettler said he would ask the City Council to outlaw cabaret shows.

“Cabarets have caused so much trouble,” he told aldermen. Schuettler summed up the Police Department’s findings in a letter to the City Council’s license committee:

Two hundred and twenty-seven cabarets have been investigated. … Of this number 208 have been reported by members of the department as having violated one or more of the laws, ordinances and police rules as shown below:

Prostitutes frequenting and soliciting, drinks served to intoxicated persons, suggestive singing, suggestive dancing—both by patrons and entertainers; hosts and hostesses employed to introduce patrons, unescorted women frequenting, pink teas conducted, soldiers and sailors in uniform served, entertainers mingling with patrons, Sunday closing law violations, 1 o’clock closing ordinance violated, prostitutes waiting in toilet rooms for calls by men and minors allowed in and served.57

The New York Clipper, an entertainment newspaper, said Schuettler’s proposal to ban cabaret shows placed him among “the most radical of radicals.” Closing cabarets would hurt many hundreds of dancers, singers, skaters, comedians, and other entertainers in Chicago, the Clipper wrote.

“The cabarets have in recent years taken a prominent place in Chicago’s amusements and the number of vaudevillians employed by them is considerable,” the newspaper commented. “… a great hardship will be worked upon those who have made their livelihood by entertaining the patrons of cabarets.”

Green Mill Gardens and several other establishments—including Bismarck Gardens and the new Moulin Rouge on Clark Street—hired a former City Hall lawyer, Harry Gancy, to represent them in the fight against a cabaret ban. Gancy said these places had invested close to a million dollars. Instead of banning cabaret, the city could increase the license fee for saloons and impose cabaret regulations, he suggested.58

The Chicago Daily News remarked: “John Barleycorn waits out in the alley for the jazz cabaret to join him on the journey to oblivion.”59

In November 1917, a Daily News writer explained the reasons why some people believed that jazz had an “immoral influence on the susceptible.” According to this viewpoint, “Music should leave one in a state of contentment.”

The writer (who used only the initials M.R.) described jazz as “a raucous perversion of the already low grade of music known as rag time.” Rather than putting young people in a state of contentment, jazz made them want to dance, as M.R. observed:

Young persons want refreshments, excitement. Perhaps they want to dance, especially the new dances, which have less formality and perhaps also less restraint, than the old time minuet, the pavande, the sarrabande, the quadrille or the waltz, and the “jazz” music with its strong rhythm, its noisy instrumental combination, its vim and go, excites the patrons to dance.

M.R. attended a show by a jazz band (without reporting the band’s name or where it was playing) and observed the performance:

“Let us jazz’m for ’em,” says the leader of the band, and soon a rag time piece with lots of noise is found and played and the dance is on.

A typical “jazz” band consists of five instrumentalists. One under consideration had a cornetist (leader), a clarinetist, a trombonist, a pianist and a drummer. This last has besides a bass and snare drum, several cow bells, which lie on top of the bass drum within easy reach of his drum sticks, a xylophone with either steel or wooden keys, cymbals, sleigh bells and other percussion paraphernalia, while both the cornet and the trombone performer have tin pails of different sizes which they hang on the bells of their instruments for the purpose of giving their instruments a reedy tone and more resonance.

The players try their utmost to make as much noise as possible and in the midst of their endeavors to extract every ounce of rhythm and every possible atom of power from their combined instruments, they gyrate and become somewhat obstreperous.

This particular band is composed of five really excellent musicians and they all have enormously developed technical facility, besides being very good sight readers. As an example of their ability, they performed at sight, with astonishing ease and exactness, two ragtime pieces, one called “The Old Town Pump,” which had just been brought in by an agent of a popular music publishing house.

After beginning the article with what seemed like a condemnation of jazz’s musical and moral “perversion,” M.R. concluded that the music wasn’t so bad after all:

As far as a couple of hours sojourn in that cabaret disclosed to me there were no visible effects upon the morals of those who danced to the music, which the “jazz” band played, aside from the actual dancing which compared to that seen at any fashionable dance or downtown cafe where there is dancing and dining. …

I cannot see or hear anything really vicious or immoral in the music of the “jazz” band any more than in any other combination of players who will play for cabaret dancing and for the entertainment of our less cultured population. It may not act as a stimulus to hear better music, but its reaction on those who hear it is certainly individual.60

As American men joined the Armed Forces and began training to fight in Europe, jazz bands became a regular part of the U.S. military. Fifty African Americans from Chicago enlisted one day at a site where a jazz band was playing, prompting the Rock Island Argus to joke—rather cluelessly—that these young Black men must have signed up to escape the noise.61

At Camp Grant in Rockford, a jazz band was part of Company C of the 33rd machine gun battalion, which included men from Chicago’s Edgewater, Irving Park, Ravenswood, and Rogers Park neighborhoods.62 Meanwhile, a company of men from the University of Chicago in Hyde Park played jazz in Barracks 1,806 at Camp Grant. After watching a performance, a Daily News reporter commented:

Everybody was grinning and not a few had their shoulders undulating in time to the music, for be it known that impromptu orchestra was putting the real jazz into its efforts—the kind of music that just naturally makes a fellow’s shoulders slide around in spite of himself. It was lively, full of the spirit of these men. … They want songs and music with the real kick in them …

Some one has called this national army the “jazz army”—not half bad. It is full of ragtime and syncopation, just the sort of thing that is going to characterize the Americans “over there” more than anything else except their fighting.63

Congress votes for Prohibition

As 1917 came to a close, the national campaign to prohibit alcohol reached a major milestone. On December 17, the U.S. House of Representatives voted 282 to 128 to send a constitutional amendment to the states.64

“The House crammed its discussion of the resolution into a single afternoon,” historian Daniel Okrent wrote in his book Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. “Who could object? The real debate had been taking place for more than sixty years.”

Some leaders in the “dry” movement said this wasn’t really a vote on the question of whether to prohibit alcohol. Instead, they said, Congress was merely submitting the amendment to the states, so that the states could decide what to do. If legislatures in 36 states voted to ratify the amendment, then “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States” would be prohibited. 65

The Chicago Brewers’ Association denounced Congress for surrendering to demands for prohibition.

“This badgering had become a menace to the political security of many congressmen,” the association said in a statement. “Not half of the congressmen voted for submission because they believe in the proposal, but because they did not wish to antagonize the hard taskmasters who demanded that they ‘come across.’”66

According to Okrent’s history, many members of Congress were “wet-drys.” In other words, they voted for “dry” laws prohibiting alcohol, but they were “wet” in their private lives, regularly drinking alcohol. Meanwhile, the groups that opposed prohibition—led by distillers, brewers, and saloonkeepers—failed to present a unified front.

“The Non-Drinkers had been organizing for fifty years and the Drinkers had no organization whatever,” Chicago journalist and author George Ade wrote. “They had been too busy drinking.”67

Eighteen members of the Illinois delegation in the U.S. House voted in favor of submitting the 18th Amendment to the states. Three Illinois congressmen were absent, and five voted no.68 Four of those “no” votes were cast by congressmen from Chicago (pictured above, from left to right):

— Republican Martin B. Madden, an immigrant from England who’d been a quarry owner.69

— Democrat Adolph J. Sabath, a Jewish lawyer who’d immigrated from the Austrian Empire, and who would become a leading voice against immigration restrictions and Prohibition.70

— Democrat Thomas Gallagher, a New Hampshire native who’d worked in iron molding, hats, and banks.71

— Republican Frederick A. Britten, a native of Chicago who’d been a construction worker and business executive.72

They were joined in their opposition by one congressman from downstate Illinois, Republican William A. Rodenberg (pictured above, at far right), a lawyer from East St. Louis whose parents were German immigrants.73

The Reverend Joseph McNamee, pastor of St. David’s Roman Catholic Church in Chicago, said the government should give compensation to people who would lose their livelihoods if prohibition became the law.

“I would favor the government buying the saloon fixtures and turning the bronze into bullets with which to fight the kaiser and buying the alcohol for munition purposes,” he remarked.74

A day after the House vote, the Senate approved the same resolution by a vote of 47 to 8. Now, the amendment went to the state legislatures for ratification.

Just a few days before the vote in Congress, the president of Chicago’s Moulin Rouge, John M. Kantor, had announced that his venue would stop serving alcohol “as a war time efficiency measure.” Inside Moulin Rouge’s “winter palace,” only coffee, tea, and chocolate would be served to dancers.75

Just before Christmas, police officers went into Green Mill Gardens and the Moulin Rouge on a Sunday, taking drinks from the tables and pouring them into bottles they were carrying. The head of the Chicago police’s morals squad, Major M.L.C. Funkhouser, planned to arrest the proprietors on charges of selling liquor on Sundays.

“I am going to see the mayor and find out if Major Funkhouser’s men can come into my place and take drinks away from my patrons,” Kantor said. “I will have these fellows out to the ‘tall timbers’ for this.” Kantor denied that he’d violated the law.

As with many such stories reported in the newspapers, it’s not clear what the outcome of this police action was. Green Mill Gardens and the Moulin Rouge stayed open.76

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Footnotes

1 Document 7048590, Book 16543, 510-514, proposed agreement between Catherine and Charles Hoffman and Tom Chamales, February 1, 1917, recorded January 28, 1921, Cook County Clerk’s Office Recordings Division.

2 Advertisement, Chicago Daily News, January 19, 1917, 15.

3 “Chords and Discords: Few by Charlie Leedy,” Rock Island (IL) Argus, April 30, 1917, 7. Reprint from Youngstown (OH) Telegram.

4 “News of the Day Concerning Chicago,” Day Book, January 25, 1917, 6; “Good-bye Griffith; Enter Paderewski,” Santa Ana (CA) Register, February 16, 1917, 7.

5 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, June 14, 1917, 7.

6 “Borrowed Records,” Chicago Daily News, May 22, 1917, 8.

7 “Jazziest Jazz,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 18, 1917, 15.

8 Advertisement, Chicago Daily News, October 1, 1917, 7.

9 “Hit or Miss,” Chicago Daily News, September 28, 1917, 8.

10 “Hit or Miss,” Chicago Daily News, October 16, 1917, 8.

11 Rube Goldberg, “Maybe the Jazz Band Can Be Included Among the Horrors of War,” Chicago Daily News, September 21, 1917, 2.

12 John V.A. Weaver Jr., “A Bas La Jazz,” Chicago Daily News, October 17, 1917, 12.

13 “U.S. Entry into World War I, 1917,” U.S. Department of State, Office of the U.S. Historian, accessed August 29, 2023, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1914-1920/wwi.

14 Lloyd Wendt and Herman Kogan, Big Bill of Chicago (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1953; Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2005), 158.

15 Daniel Okrent, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (New York: Scribner, 2010), 99.

16 Okrent, Last Call, 85.

17 Okrent, Last Call, 100.

18 “Summer Gardens & Picnic Groves,” Jazz Age Chicago, accessed May 23, 2023, https://jazzagechicago.wordpress.com/summer-gardens-picnic-groves/.

19 “Bismarck Garden to Drop Its German Label,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 7, 1917, 1.

20 Paul Kruty, “Pleasure Garden on the Midway,” Chicago History, fall-winter 1987-88, 22.

21 Paul Durica, “Illinois’ Nazi Brewers?: Was Pilsen’s Schoenhofen Brewery A Front?” Mash Tun Journal 3, 2013, accessed August 29, 2023, https://mashtunjournal.org/texts/brewery; Peter Schoenhofen, Case Number 73621, Investigative Case Files of the Bureau of Investigation 1908-1922, National Archives Publication M1085, Series: Old German Files, 1909-21, Roll 0323, Fold3.com.

22 “Revue Built Round Song,” New York Clipper, May 2, 1917, https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=NYC19170502.2.139&srpos=25&e=——-en-20–21-byDA-img-txIN-%22green+mill+gardens%22———.

23 “Chant War Songs on Way to Scalp Kaiser,” Chicago Daily News, October 4, 1917, 2.

24 “Patricola at Green Mill,” Chicago Daily News, August 18, 1917, 16.

25 “Green Mill Entertainment,” Chicago Daily News, September 1, 1917, 14.

26 “Patricola at Green Mill.”

27 “Gorman Brothers,” Wikipedia, accessed June 5, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gorman_Brothers; R.M. Harrison, “The Theatre and Its People,” Windsor (Ontario) Star, February 1, 1928, 10.

28 “Joseph Heleluhe,” Wikipedia, accessed June 5, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Heleluhe; advertisement, (Knoxville, TN) Journal and Tribune, April 22, 1919, 2.

29 “Patricola at Green Mill.”

30 “At Parks and Gardens,” Chicago Daily News, June 2, 1917, 16; “Green Mill,” Chicago Daily News, June 16, 1917, 15. Spelling: Scranton Republican, September 1, 1907, 7; Arnold Woods, “Fillmore Chutes: A Closer Look,” OpenSFHistory, accessed June 5, 2023, https://www.opensfhistory.org/osfhcrucible/2020/08/09/fillmore-chutes-a-closer-look/.

31 “Green Mill,” Chicago Daily News, June 16, 1917, 15; “The Tik-Tok Man of Oz,” Wikipedia, accessed June 5, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Tik-Tok_Man_of_Oz.

32 “Marion & Randall in ‘Gallop!’” New York Clipper, May 16, 1917, 15. https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=NYC19170516.2.149&srpos=27&e=——-en-20–21-byDA-img-txIN-%22green+mill+gardens%22——–.

33 “Ralph Dunbar’s Tennessee Ten,” Vaudeville America, accessed June 5, 2023, http://vaudevilleamerica.org/performance/ralph-dunbars-tennessee-ten-2/; Karl Koenig, “Jazz Studies 4,” Basin Street, 2017, http://basinstreet.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Jazz-Studies-I11.pdf, 66-79.

34 “Tennessee Ten,” Chicago Defender, July 28, 1917, 4; advertisement, Chicago Daily News, August 11, 1917, 8; “Fun at Parks and Gardens,” Chicago Daily News, August 11, 1917, 16.

35 “Tennessee Ten,” Chicago Defender, October 6, 1917, 4.

36 “The Majestic,” Flint (MI) Journal, February 9, 1917, 10.

37 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, May 27, 1917, part 7, 4.

38 “Opening of the Moulin Rouge,” Chicago Daily News, May 26, 1917, 14.

39 U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, Ancestry.com; Albert Bouche, Find a Grave, accessed June 17, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/71545535/albert-bouche; “Club Owner ‘Papa’ Bouche Dies at 83,” (Hollywood, FL) Sun-Tattler, August 7, 1964, 1, 2.

40 “Moulin Rouge, City’s New Summer Garden, to Open,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 27, 1917, 10.

41 Advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, May 27, 1917, part 7, 4.

42 “Opening of the Moulin Rouge,” Chicago Daily News, May 26, 1917, 14.

43 Mike Brubaker, “The Great Luigi D’Urbano and His Royal Italian Band,” Temposenzatempo, March 28, 2013, https://temposenzatempo.blogspot.com/2013/03/the-great-luigi-durbano-and-his-royal.html.

44 “Old ‘Newsies’ to Set Day,” Chicago Daily Tribune, Jan. 7, 1916, 5; “Mayor’s Aid Ex-Convict?” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 19, 1916, 16; “City Attorney’s Office Shift,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 6, 1916, 10.

45 Moulin Rouge Garden corporation papers, Secretary of State (Corporations Division): Dissolved Domestic Corporation Charters, 103/112, Illinois State Archives, Springfield.

46 “Moulin Rouge Gardens Defendant in Bankruptcy,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 18, 1918, 17.

47 U.S., Passport Applications, 1925, Volume 15: Special Series—Chicago, Ancestry.com.

48 “Opera Club and Ciro’s to Open as Public Cafe,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 24, 1933, part 7, 3.

49 Eric Durr, “‘Rainbow Division’ that represented the United States formed in New York in August 1917,” U.S. Army, July 24, 2017, https://www.army.mil/article/191270/rainbow_division_that_represented_the_united_states_formed_in_new_york_in_august_1917.

50 “Old Rainbo Gardens Will Get New Look,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 29, 1957, part 3, 2.

51 “Rob Green Mill Gardens,” Chicago Daily News, July 30, 1917, 3.

52 “In Chicago,” Hotel World 85 (Aug. 4, 1917), 39. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112089612250?urlappend=%3Bseq=187%3Bownerid=13510798903771001-203.

53 “Green Mill Robbery Suspects Are Freed,” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 27, 1917.

54 FBI Case Files, Old German Files, 1909-21, “Various (#8000-7702),” 153, Fold3.com.

55 “Hit or Miss: Consequences,” Chicago Daily News, September 10, 1917, 8.

56 “Eitels Close Bluebird Room; Raids Net 200,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 22, 1917, 1, 10.

57 “Cabarets here Are on Trial for Lives,” Chicago Daily News, November 1, 1917-11, 1.

58 “Schuettler Is Against the Cabarets,” New York Clipper, October 24, 1917, 12. https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=NYC19171024.2.112&srpos=38&e=——-en-20–21-byDA-img-txIN-%22green+mill+gardens%22———.

59 Chicago Daily News, October 27, 1917, 8.

60 M.R., “About the Jazz Bands and Cabaret Music,” Chicago Daily News, November 17, 1917, 12.

61 “Chords and Discords,” Rock Island (IL) Argus, April 17, 1917, 7.

62 Paul R. Leach, “Drill at Rockford in Snow; 16 Above,” Chicago Daily News, October 30, 1917, 3.

63 “Found: Friendliest Company,” Chicago Daily News, November 17, 1917, 3.

64 “Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution,” Wikipedia, accessed August 28, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eighteenth_Amendment_to_the_United_States_Constitution.

65 Okrent, Last Call, 91, 94.

66 “Illinois ‘Drys’ Get Busy,” Chicago Daily News, December 18, 1917, 7.

67 Okrent, Last Call, 83, 89.

68 Arthur Sears Henning, “House Votes for Dry America,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 18, 1917, 1-2.

69 “Martin B. Madden,” Wikipedia, accessed August 29, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_B._Madden.

70 “Adolph J. Sabath,” Wikipedia, accessed August 29, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolph_J._Sabath.

71 “Thomas Gallagher (Illinois Politician),” Wikipedia, accessed August 29, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Gallagher_(Illinois_politician).

72 “Frederick A. Britten,” Wikipedia, accessed August 29, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_A._Britten.

73 “William A. Rodenberg,” Wikipedia, accessed August 29, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_A._Rodenberg.

74 “Drys Will Make Illinois Drive in September,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 18, 1917, 2.

75 “Alcohol Barred at Gardens,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 14, 1917, 11.

76 “Three Big Cafes Face Charged of Tilting the Lid,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 25, 1917, 17.