Chapter 15 of

The Coolest Spot in Chicago:

A History of Green Mill Gardens and the Beginnings of Uptown

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER—>

In 1916, the Day Book newspaper said Green Mill Gardens was one of Chicago’s “three big personal liberty gardens.”

The other two were Bismarck Gardens—located a mile and half away, at Grace and Halsted Streets—and Edelweiss, formerly known as Midway Gardens, at Cottage Grove Avenue and 60th Street down on the South Side. “Personal liberty” had been a common expression in Chicago for many years. To many people, it meant being able to drink whenever they wanted. Green Mill Gardens and its two big competitors seemed to exemplify that spirit.

But the Day Book was being a little ironic when it called them “personal liberty gardens.” The newspaper reported that all three of these places were fighting against organized labor. Joining a union was a sort of liberty they didn’t tolerate.

“A bartender in the big beer gardens dare not belong to the American Federation of Labor,” the Day Book reported. “It would mean his job.”1

As 1916 began, reformers’ complaints grew louder about Chicago cabarets—including “fox trot clubs” inside Loop hotels, where many girls reportedly met their “downfalls.”2 One woman, who was charged with soliciting for prostitution, testified that “men and women slung the drinks and did close-up bunny hugs until 4 o’clock in the morning” at one of these foxtrot clubs.3

Some people were shocked when they read these newspaper reports about places in Chicago with “saxophone music, fox-trotting, risqué entertainment, open promiscuity, wholesale intoxication and cigarette smoking, prostitutes, shop girls, and slumming society,” sociologist Walter C. Reckless recalled in 1933. Looking back on these reports, he described those early months of 1916 as the “first new manifestation of the jazz age.”4

No one called it that at the time. The word jazz had surfaced as a musical term in the Chicago Daily Tribune in July 1915, but it doesn’t appear that anyone else wrote anything about jazz music over the following nine months. And certainly, no one was talking about living in the Jazz Age.

But that phrase would enter common parlance within a few years. People started describing their era as the Jazz Age around 1919, three years before F. Scott Fitzgerald used the phrase in one of his book titles.5 According to music historian William Howland Kenney, Jazz Age “can be used to describe ‘Roaring Twenties’ social dance music and assorted activities, such as going out to dance halls and cabarets, going to the movies, dressing like ‘sheiks,’ ‘shebas,’ and ‘flappers,’ and drinking bootleg gin. These activities, like jazz itself, were ‘jazzy’ urban behaviors that expressed the excitement, adventure, glamour, sensuality, and daring stimulated in young urban Americans.”6

But that phrase would enter common parlance within a few years. People started describing their era as the Jazz Age around 1919, three years before F. Scott Fitzgerald used the phrase in one of his book titles.5 According to music historian William Howland Kenney, Jazz Age “can be used to describe ‘Roaring Twenties’ social dance music and assorted activities, such as going out to dance halls and cabarets, going to the movies, dressing like ‘sheiks,’ ‘shebas,’ and ‘flappers,’ and drinking bootleg gin. These activities, like jazz itself, were ‘jazzy’ urban behaviors that expressed the excitement, adventure, glamour, sensuality, and daring stimulated in young urban Americans.”6

By 1916, going out to cabarets had become a popular way for young people to spend the night, according to the Juvenile Protective Association’s Louise DeKoven Bowen (one of those reformers who hated cabarets).

“Many a young man who asks a girl to go to a movie with him of an evening, after they have seen the film feels that he has not been gallant unless he takes his girl to a cabaret, where if he buys a few drinks they can hear the singing, dance, and ‘get on’ to the newest steps as demonstrated by professionals,” Bowen wrote.7

The Juvenile Protective Association and other reformers—the folks who wanted to restrict alcohol sales and prostitution—had been pushing for a crackdown on dance halls, where special bar permits allowed alcohol to be served until 3 a.m. The JPA complained that these permits were often issued to “‘fly by night’ clubs who have no financial or moral standing.” 8

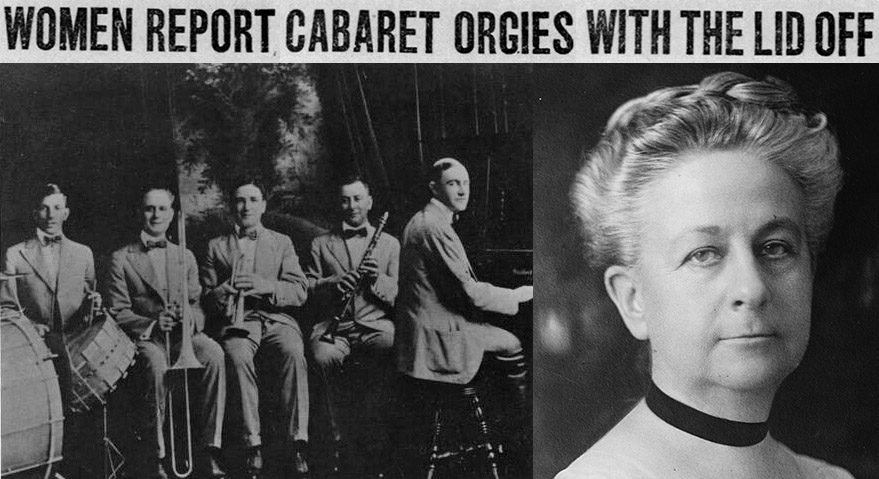

The leading voice against dance halls was the wife of Charles E. Merriam,9 a South Side alderman who was a political science professor at the University of Chicago. Although her name was Hilda, she always appeared in the newspapers as “Mrs. Charles E. Merriam.”10

“I believe that a ‘dance syndicate’ is operating in various parts of the city,” she said, asserting that few dance halls actually served the philanthropic purposes they claimed to.11

In 1916, the JPA reported that the number of dance halls in Chicago had increased to about 800. “The investigators report the indiscriminate sale of liquor to minors, improper and indecent dancing, undue familiarity between young men and girls, and such flagrant indecencies that they are absolutely unprintable,” Bowen wrote.12

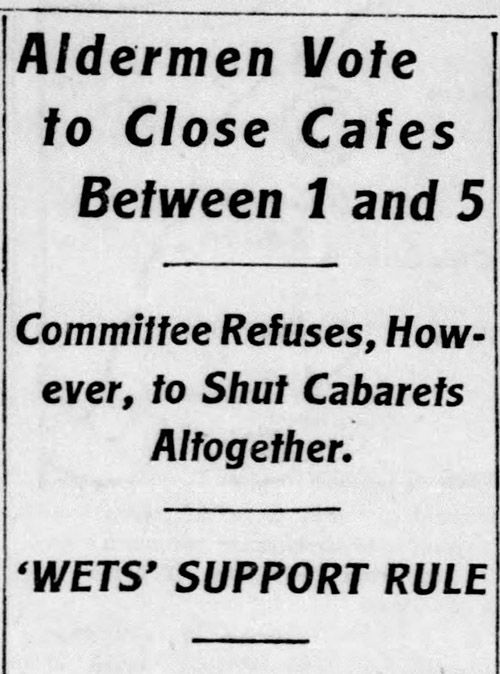

Aldermen and reformers were surprised when the city’s Law Department issued an opinion: Even though an ordinance prohibited alcohol from being served between 1 and 5 a.m., “restaurants may be open at any hour day or night,” the city’s lawyers said. If a restaurant was connected with a saloon, it could stay open after 1 a.m., as long as the bar and the restaurant were in separate rooms.13

Reformers worried that this would make it easy for saloons to keep serving liquor after 1 a.m. “In some of the saloons where they ostensibly do not sell liquor after one o’clock, it is sold by taking bottle from buckets which are placed at midnight under tables in a certain portion of the room,” Bowen wrote. “It is very usual, unfortunately, to see girls at these cabarets who have become intoxicated, and who are guilty of immodest actions of which they would be incapable were they not under the influence of liquor.”

Allowing restaurants to stay open after 1 a.m. also created an opportunity for all-night cabaret performances in these places. And that presented other worries for reformers like Bowen.

“Cabaret singers are required to be on duty between one and five o’clock in the morning,” she wrote. “… The dancing floor in the cabaret is usually a small space, which is used by the entertainers and by the patrons themselves who dance. When the floor is very crowded, as is often the case, the couples are really unable to move, and they stand in one place going through the motions of dancing, sometimes in a vile manner.”14

Under growing pressure, the City Council changed the law, requiring any restaurants that served alcohol to close at 1 a.m. It was a the unanimous vote. Even Bathhouse John Coughlin and Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna voted for it,15 though Coughlin had spoken out against the idea earlier, declaring, “I am a bohemian, and this ordinance curtails personal liberty.”16

Alderman Robert M. Buck proposed outlawing all cabaret performances at saloons and restaurants,17 to “save the morals of the city from being undermined by the vile and vicious cabarets.”18Alderman John N. Kimball remarked: “Cabarets and assignation houses are taking the place of the old-time red-light district.”19

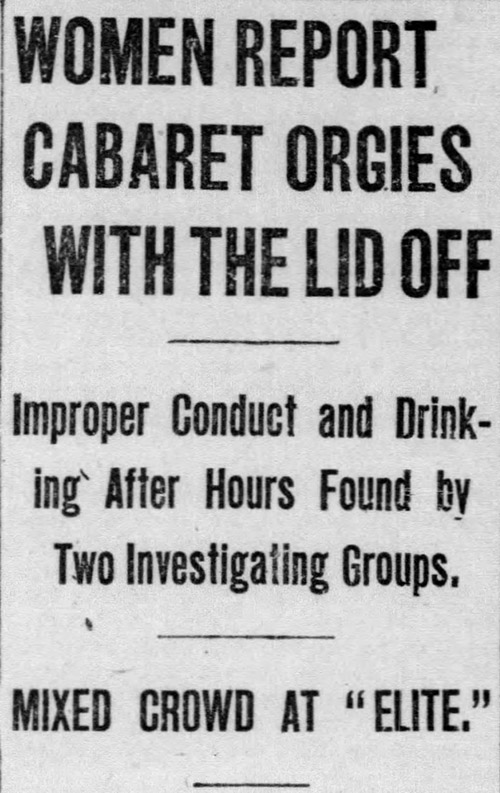

“Orgies with the lid off”

At one session, the aldermen heard reports about cabarets including Colosimo’s and the New Delaware, 1733 West Madison Street, which was known as “The Bucket of Blood.” The Tribune reported: “Stories of debauchery related by the witnesses stunned the aldermen.”20 After Mrs. Merriam’s investigators visited cabarets, a headline reported that they’d witnessed “orgies with the lid off.”21

Mrs. Charles E. Merriam took a tour of several cabarets in the late hours of Saturday, April 29, and the early morning hours of that Sunday. Her entourage included another City Council spouse—Sophia Rodriguez, the wife of a 15th Ward alderman William E. Rodriguez22—as well as some reporters.

Starting their evening in the Loop, the ladies and journalists made their way to the South Side, where they found a crowd clamoring to get inside the New Schiller Cafe, 318 East 31st Street, around 2:30 a.m. “Can’t come in!” the club’s sweaty doorman shouted. “We’re crowded to capacity. Wait ‘till some of the others come out.”

Mrs. Merriam’s group finally gained admittance to the crowded club. A reporter for the Chicago Herald described what they witnessed inside:

It was impossible for anyone to be heard. The shriek of women’s drunken laughter rivaled the blatant scream of the imported New Orleans Jass Band, which never seemed to stop playing. Men and women sat, arms about each other, singing, shouting, making the night hideous…

After experiencing the “blatant scream” of Stein’s Dixie Jass Band at the Schiller Café in the early morning hours of April 30, Mrs. Merriam and her investigators headed to the Elite, 3030 South State Street, around 3:30 a.m. The crowd fighting in get inside the Elite was even larger than the one the investigators had encountered outside the Schiller. The Elite was a black-and-tan, where Black and white people mixed in the audience.

That fact was enough to alarm the Herald reporter tagging along with Mrs. Merriam’s group. The newspaper reported:

Blacks and whites mixed indiscriminately, drinking together, were cheering a negro couple dancing the “chemise tail.” A description of the dance cannot be printed. The sights witnessed by the women in the party were such as they declared later they had not dreamed were possible.

When Mrs. Merriam and her sin-seeking sleuths had completed their tour of Chicago cabarets, the Herald summed up their consensus of opinion: “We are sick at heart,” they said.23

Published on May 1, 1916, this Chicago Herald article is the second known time in history that anyone wrote about jazz music (following the July 15, 1915, Tribune story by Gordon Seagrove).

“Give us some more jass!”

A Chicago club manager named Harry James had arranged for this New Orleans group to come to Chicago in March 1916.24 At first the musicians called themselves Stein’s Band From Dixie—echoing the way Brown’s Band From Dixeland had been billed the previous year at the Lambs’ Café in downtown Chicago.

In a 1960 book, author H.O. Brunn recounted a story about how jass was added to the name of Stein’s Band. At the time he was writing, Brunn didn’t know about that 1915 Tribune article describing jazz music, which historians have discovered in the years since. He also seemed unaware of stories about people using the word jazz to describe Brown’s Band in 1915—such as cornet player Ray Lopez’s anecdote about Darby Kelly yelling “Jazz it up, Ray!”

And so, when Brunn wrote in 1960, he believed—incorrectly—that the spring of 1916 was the first time anyone used jazz or jass as a musical term. The narrative he wrote is strikingly similar to the one Lopez told about the events of 1915. Here’s how Brunn told the tale in his book (which relied heavily on interviews with the cornet player for Stein’s Band, Nick LaRocca):

It was during their run at Schiller’s that the word “jass” was first applied to music. A retired vaudeville entertainer, somewhat titilated by straight blended whiskey and inspired by the throbbing tempos of this lively band, stood at his table and shouted, “Jass it up, boys!”

“Jass,” in the licentious slang vocabulary of the vast Chicago underworld, was an obscene word but like many four-letter words of its genre, it had been applied to almost anything and everything and had become so broad in its usage that the exact meaning had become obscure to most people.

Harry James, now the manager of Schiller’s, never missed a bet. When the unidentified inebriate bellowed forth his now-famous “Jass it up, boys!” (and by so doing, unwittingly wrote a full page of musical history), the gold-plated thinking machinery of the Chicago cafe expert was once more set in motion. The tipsy vaudevillian was hired to sit at his table and shout “Jass it up,” every time he felt like it—all drinks on the house. The next day the band was billed, in blazing red letters across the front of Schiller’s:

STEIN’S DIXIE JASS BAND

Chicagoans then had a word for the heretofore unnamed music.25

Ray Lopez, who attended the first show by Stein’s Band in Chicago, described the Schiller Café as “a honky-tonk place … strictly a sawdust joint catering to a lot of pimps and whores.” As far as Stein’s Band, Lopez criticized LaRocca’s playing and commented: “The band was just a lot of noise, and I don’t say that to belittle them.”26 For his part, LaRocca recalled how his band created a sensation in Chicago:

After the sensation we created, other cafe owners sent to New Orleans for men who were supposed to play our kind of music. They imported anybody that could blow an instrument, and they all had “New Orleans Jass Band” in front of their places. … We were never advertised in the papers, as every night was a full house. … The impact we had on the people of Chicago was terrific. Women stood up on the dance floor, doing wild dances. They had to pull them off the floor. The more they would carry on, the better we could play. Here is where the singers came to the rescue, as these patrons would never leave the floor and the manager wanted them to sit and drink. Then the crowd would start yelling, “Give us some more jass.” I can still see these women who would try and put on a show dance, raise their dresses above their knees and carry on, men shrieking and everybody having a good time. I would let go a horse whinny on my cornet and the house would go wild.27

Sometime in March or April,28 Stein’s Band began playing a tune that would end up as the subject of plagiarism litigation, “Livery Stable Blues.” Lopez and another member of Brown’s Band, trombonist Tom Brown, alleged it was a rip-off of a song each of them said they’d written earlier, “More Power Blues.” They said it was the same tune, with the added novelty of horns imitating the noises of barnyard animals.29 The clarinetist in Stein’s Band, Alcide Nunez, said that Lopez had written the original.30

But LaRocca told a colorful story about how he’d started making his cornet sound like a horse when the band was playing at the Schiller Café. LaRocca testified:

Well, a valve in my cornet got stuck and it made a funny noise. I experimented with the bray or neigh, and finally worked out my “Livery Stable” melody. One day when our band had finished playing a number at the Schiller Café, here in Chicago, there was a girl sort of skylarking around the floor, and I blew a horse neigh at her on my cornet. She laughed. … And then I taught my composition to the band. The clarinet played a rooster call, the trombone a cow moo or a donkey bray and I the horse neigh on my cornet. Everybody liked it.31

The group’s trombonist, Eddie Edwards, gave similar testimony:

There were several people in the Schiller’s Café and one girl in particular was evidently feeling jolly and skylarking to the amusement of the boys in the band, which prompted LaRocca to pick up the cornet and play a horse whine on it and everybody laughed within hearing distance of it. … I told him it would be a good stunt to put this horse whine in a number, and he said he had it in a number and I, of course, asked him what number it was, and he replied “A Blue number.” I told him some time we might try it and it might prove a good number to us.

Asked to define “a blue number,” Edwards said that was a phrase musicians used for a “fox trot with a slow and lazy like yawning with no direct harmony, sort of freak harmony.”32

Four members of Stein’s Band—everyone except for drummer Johnny Stein—left the group at the end of May, deciding they needed to make more money than the $25 weekly pay at Schiller’s Café. LaRocca, Nunez, Edwards, and pianist Henry Ragas joined with drummer Anthony Sbarbaro to form the Original Dixieland Jass Band, playing first at the Del’Abee Café, in the Normandie Hotel, 417 South Wabash Avenue, and later that year at the Casino Gardens, Kinzie and Clark Streets.33

What is “cabaret,” anyway?

Meanwhile, Chicago’s aldermen were struggling to define what exactly “cabaret” entertainment was as they tried to crack down on it. After months of work, a committee chaired by alderman Otto Kerner (the father of future Illinois governor Otto Kerner Jr.) came up with this convoluted definition:

A cabaret performance was “music, dancing, vaudeville and theatrical performances of any and all kinds and descriptions, except such musical performances either instrumental or vocal as may be presented by performers in ordinary street or evening attire who shall not go about among or mingle with the patrons.”34

The Tribune pointed out that definitions like this would prohibit operatic, vaudeville, and dancing shows at Green Mill Gardens, Bismarck Gardens, and Edelweiss Gardens, while legalizing “the honky tonk.”35

A Tribune editorial dismissed the quality of cabaret shows: “The entertainers are generally quite the reverse of entertaining. Unless you like noise you cannot really like the cabaret.” But the newspaper questioned whether it would do any good to prohibit entertainment in places where food and drink are dispensed. Cabarets were simply the latest scapegoat. “The trouble arises from the fact that young people like to meet together and have a good time,” the Tribune observed. “… Instead of stressing the smashing of cabarets, we should stress the building of character.”36

Green Mill Gardens teamed up with other big establishments in a campaign to fight the anti-cabaret ordinance.37 By the fall of 1916, the anti-cabaret ordinance had failed to win consensus at the City Council—for the time being.38

The forces fighting prohibition of alcohol were divided. On one side, big Chicago hotels, including the Sherman, La Salle, Bismarck, Stratford, Congress, and Blackstone, were reportedly responsible for killing the anti-cabaret ordinance. On the other side, some of the city’s saloonkeepers believed it was in their best interest to support a ban on music and dancing in drinking establishments

“The feeling of the saloonkeepers is that if the ordinance had been passed the vicious type of redlight saloons would have been checked and the reformers and newspapers would lose a valuable argument against saloons in general,” the Day Book newspaper explained. In other words, these saloonkeepers hoped they could stave off the push for a prohibition of all alcohol if they compromised and supported a crackdown against a smaller target—the sort of saloons that reformers viewed as the most “vicious.”

At the same time, these saloonkeepers opposed a proposal by Mayor Bill Thompson to increase saloon licenses to $1,500. They argued that the higher license fee would force many small taverns around the city to shut down, while dive bars in the “river wards” and the Black Belt would thrive in spite of the increase—because those saloons were allegedly supported by breweries.

According to this argument, the higher license fees would cause breweries to “concentrate saloons in the tougher districts, where the music and women would provide entertainment and, therefore, increase the business,” the Day Book reported.39

Green Mill Gardens shows in 1916

George K. Spoor, the owner of the Essanay movie studio, hosted a luncheon for the Advertising Association of Chicago at Green Mill Gardens on St. Patrick’s Day of 1916. Police superintendent Charles C. Healey and a squad of mounted police officers led a procession of the 80 automobiles to the event, filmed by Essanay.40

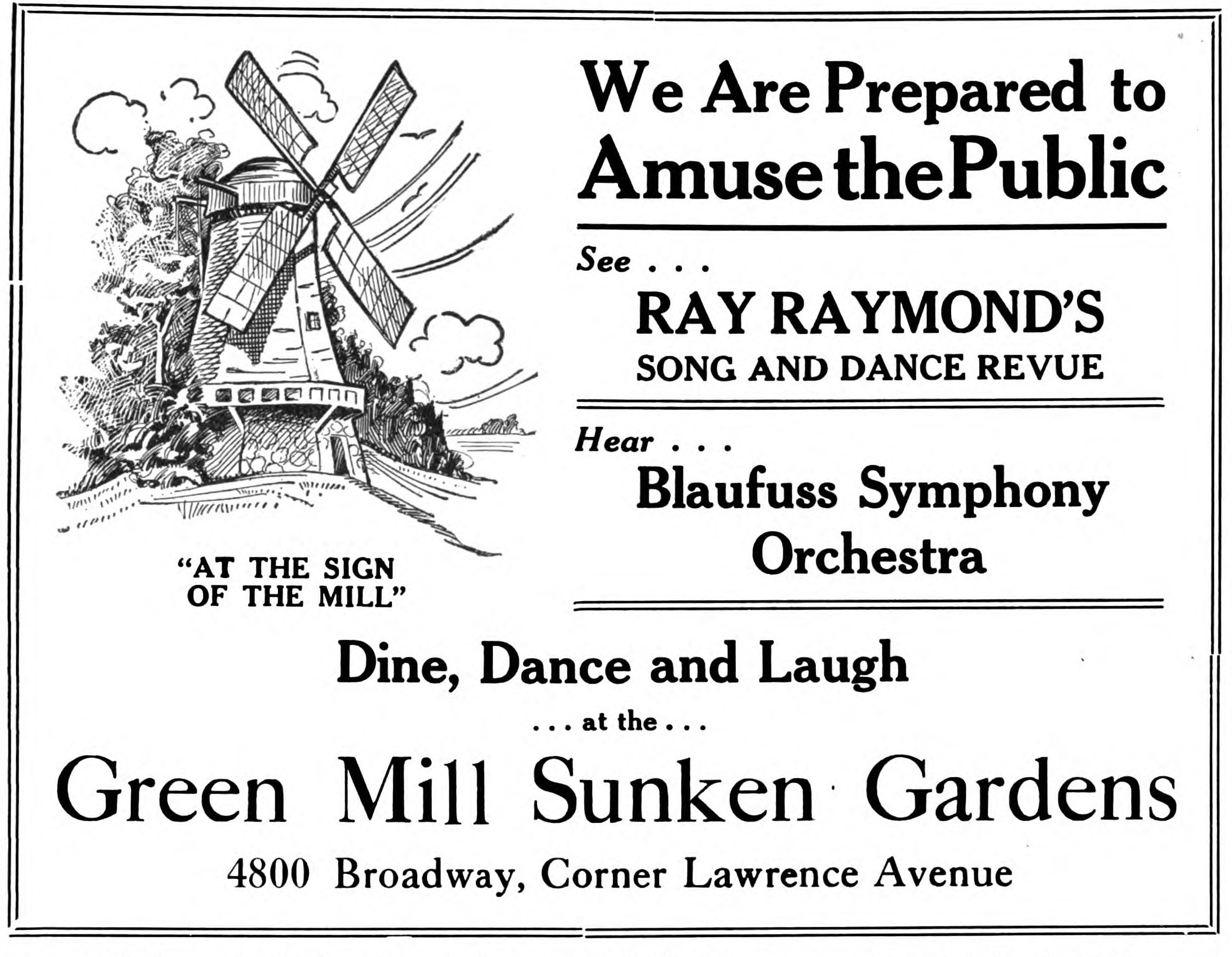

Ray Raymond, the comedic actor-singer who’d performed at Green Mill Gardens in 1915, returned to the venue for the summer season in 1916, leading “his company of nimble girls,” in a musical and dancing revue, with an orchestra of 30 musicians conducted by Walter Blaufuss.41 (The Milwaukee native, who would write the 1919 hit songs “Your Eyes Have Told Me So” and “My Isle of Golden Dreams,” also performed for many years at Chicago’s Tip Top Inn.42)

Walter Blaufuss, from the 1942 Breakfast Club Family Album, via richsamuels.com.

“We Are Prepared to Amuse the Public,” a June 1916 advertisement proclaimed. “Dine, Dance and Laugh … at the … Green Mill Sunken Gardens … ’AT THE SIGN OF THE MILL.’”43 Meanwhile, the Daily News reported that Green Mill Gardens’ management was using the slogan “Laugh at the Thermometer,” suggesting that the sunken garden felt cool even on warm days. “In the evenings Walter Blaufuss’ orchestra, under his personal direction, mingles melodies with the breeze,” the newspaper said.44

But before June was over, Raymond left under mysterious circumstances. “Ray Raymond’s review terminated, suddenly, last Saturday night, at the Green Mill Gardens,” the New York Clipper reported.45 (Raymond would meet a tragic end in Los Angeles in 1927, when he was beaten to death by another actor, Paul Kelly, in a fight over Raymond’s wife, Dorothy Mackaye. Kelly was found guilty of manslaughter, and Mackaye was convicted of concealing evidence.46)

Other entertainment at Green Mill Gardens that summer included the Kilties, who were billed as “Canada’s Greatest Concert Band.”47

On August 16, 1916, the Morse corporation finally got around to changing its name, formally becoming Green Mill Gardens. At the same time, the corporation authorized an increase in its capital stock from $30,000 to $250,000—but papers filed with the state don’t make it clear whether the corporation ever issued that additional stock.48

More mentions of jazz

The word jazz—sometimes spelled jass or jaz—began appearing in newspaper articles and advertisements in the fall of 1916. On September 30, the Chicago Defender wrote about Estelle Harris appearing at the Grand Theater with her “jass singers and dancers.”49

Someone named Moore took out a “situation wanted” classified ad in the Tribune on November 1, offering the services of “Colored Jazz Singers, Pianists.”50

In early December, music stores—including Wurlitzer and Lyon & Healy, both located on Wabash Avenue in Chicago’s Loop—began advertising rolls for player pianos that featured jazz music. “Do not fail to hear these two dance rolls recorded with the special ‘Jazz’ obligator arrangement,” Wurlitzer’s ad said, promoting the songs “Bull Frog Blues” and “Whose Pretty Baby Are You Now.”51

On December 9, the Indianapolis Freeman published this notice: “Thos. A Brooks and the Heart of Dixie company are at the Orpheum theatre, Milwaukee, with Chicago to follow. Watch for my new and latest composition, The Jazz Band King.”52 A week later, the Freeman reported that composer W. Benton Overstreet had introduced a song called the “Jaz Dance” at Chicago’s Haymarket Theatre.53

New Year’s plans vetoed

In November 1916, police superintendent Charles Healey warned Green Mill Gardens and two other big cafés—Bismarck Garden and the Rienzl, at Broadway and Diversey Parkway—that his investigators had caught them “‘sneaking’ the lid up a little.” He warned them that they could lose their licenses if they continued breaking the law against serving alcohol on Sundays.54

Green Mill Gardens and five of the other “swellest cafes in town” hoped to hold dances on New Year’s Eve of 1916, serving drinks until 3 a.m. The venues could get around the law requiring them to close at 1 a.m. if benevolent organizations received special bar permits to hold dances in their spaces.55 Six clubs stepped forward, filing applications for events at Green Mill Gardens, the Bismarck, and other venues.

But city officials rejected the permits,56 questioning whether these groups were bona fide charities. Danse de Chantacler, a “society is organized in good faith and charity and of reputation and character,” applied to hold a dance “for benevolent purposes” at Green Mill Gardens. Tom Chamales was listed as the club’s president.57 A little more than a month later, the city cited Chamales for keeping Green Mill Gardens open after 1 a.m.58

A bartender’s murder

On December 26, 1916, Albert J. Jackson was shot and killed just outside John F. Butterly’s saloon, in the north wing of the Green Mill Gardens building, where Jackson was known as “the sunshine bartender.”

The police arrested two African American men, Gilmore Lindsey and Oscar Steins (or Steino), both of whom worked as janitors at nearby buildings on Wilson Avenue. According to Butterly, Jackson had angered Lindsey when he’d refused to let him shoot craps in the bar.59 Lindsey was sentenced to life in prison, and Steins got 20 years in Joliet.60

<— PREVIOUS CHAPTER / TABLE OF CONTENTS / NEXT CHAPTER —>

Footnotes

1 Fred Ebeling, “Liberty,” Day Book, July 10, 1916, 25.

2 “City Administration Attorney Stalls Fox Trot Club Investigation,” Day Book, January 12, 1916, 12.

3 “Trust Press Forgot to Say That the Gent Is Harry Moir,” Day Book, January 20, 1916, 31.

4 Walter C. Reckless, Vice in Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1933), 101.

5 Ammon Shea, “You Didn’t Invent That: F. Scott Fitzgerald and ‘Jazz Age,’” Dictionary.com, February 24, 2015, https://www.dictionary.com/e/fitzgerald-and-jazz-age/.

6 William Howland Kenney, Chicago Jazz: A Cultural History 1904-1930 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), xiii.

7 Louise DeKoven Bowen, The Road to Destruction Made Easy in Chicago (Chicago: Juvenile Protective Association of Chicago, 1916), 12, https://books.google.com/books?id=E5Ll7wAtwzcC.

8 Bowen, Road to Destruction, 8-9.

9 Reckless, Vice in Chicago, 108-109.

10 1910 U.S. Census, Illinois, Cook, Chicago Ward 7, enumeration district 0414, sheet “supp. A,” Ancestry.com.

11 “Sees City-Wide ‘Dance Trust,’” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 5, 1915, 4.

12 Bowen, Road to Destruction, 10.

13 Journal of the Proceedings of the City Council of the City of Chicago, Illinois, vol. 80, Feb. 14, 1916, pp. 3232-3233. https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofcit80chic/page/3232/mode/2up

14 Bowen, Road to Destruction, 14.

15 Journal of the Proceedings of the City Council of the City of Chicago, Illinois, vol. 80, April 7, 1916, 4330-4331, https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofcit80chic/page/4330/mode/2up.

16 “Aldermen Vote to Close Cafes Between 1 and 5,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 14, 1916, 1.

17 Journal of the Proceedings of the City Council of the City of Chicago, Illinois, vol. 80, February 14, 1916, 3329. https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofcit80chic/page/3328/mode/2up.

18 “Ordinance Hits Cabarets of Better Class,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 23, 1916, 1.

19 “Mayor Plays Role of Target at the Council,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 22, 1916, 3.

20 “Five Cabarets Violate Law, Aldermen Hear,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 25, 1916, 5.

21 “Women Report Cabaret Orgies With the Lid Off,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 1, 1916, 15.

22 1920 U.S. Census, Illinois, Cook (Chicago), Ward 15, enumeration district 922, sheet 5B, Ancestry.com.

23 Sixty Women Rip Mask From Vice; Find Lid Tilted,” Chicago Herald, May 1, 1916, 1, 4.

24 Ray Lopez (as told to Dick Holbrook), “Mister Jazz Himself,” Storyville 64 (April-May 1976), 145-146, https://nationaljazzarchive.org.uk/explore/journals/storyville/storyville-064/1267477; H.O. Brunn, The Story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1960), 23; Richard M. Sudhalter, Lost Chords: White Musicians and Their Contribution to Jazz, 1915-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), “Bands From Dixieland” excerpt at https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/first/s/sudhalter-chords.html.

25 Brunn, Story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, 30.

26 Lopez, “Mister Jazz Himself,” 145-146.

27 Brunn, Story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, 37-38. Cited source: Nick LaRocca letter to Brunn, March 16, 1959.

28 Brunn, Story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, 34; Deposition of Bert Kelly, Hart et al. v. Graham (N.D. Ill. 1917), Case File E914; U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division (Chicago); Records of District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21; National Archives and Records Administration Great Lakes Region (Chicago). Transcription in Katherine Murphy Maskell, “Who Wrote Those ‘Livery Stable Blues’?: Authorship Rights in Jazz and Law as Evidenced in Hart et al. v. Graham,” master’s thesis, Ohio State University School of Music, 2012, https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_etd/send_file/send?accession=osu1338343959&disposition=inline, 127.

29 Deposition of Tom Brown, Hart v. Graham, Maskell transcription, 131.

30 Deposition of Alcide Nunez, Hart v. Graham, Maskell transcription, 129.

31 “At Last! Court Finds Man Who First Jazzed,” Chicago American, October 11, 1917, 1, Maskell transcription, 283-284.

32 Deposition of Edwin B. Edwards, Hart v. Graham, Maskell transcription, 172-175.

33 Brunn, Story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, 38, 41; Sudhalter, Lost Chords; deposition of Alcide Nunez, Hart v. Graham, Maskell transcription, 129; deposition of Edwin B. Edwards, Hart v. Graham, Maskell transcription, 171-172; 1916 Chicago city directory, 461, 1382, Fold3.com.

34 Journal of the Proceedings of the City Council of the City of Chicago, Illinois, vol. 82, October 16, 1916, pp. 1861-1864. https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofcit82chic/page/1860/mode/2up.

35 “Ordinance Hits Cabarets of Better Class,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 23, 1916, 1.

36 “Suppressing Symptoms,” editorial, Chicago Daily Tribune, March 5, 1916, 16.

37 “Big Cafes Line Up to Fight Booze-Dancing Divorce,” Day Book, May 23, 1916, 9.

38 Journal of the Proceedings of the City Council of the City of Chicago, Illinois, vol. 82, October 16, 1916, pp. 1861-1864. https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofcit82chic/page/1860/mode/2up.

39 “Saloonkeepers Plan to Organize for Fight on Prohibition Crusade,” Day Book, December 23, 1916, 4.

40 “Chicago Film Brevities,” Moving Picture World 28, no. 1 (April 1, 1916), 86, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015010217027?urlappend=%3Bseq=50%3Bownerid=13510798900650454-56.

41 “Summer Season at Green Mill,” Chicago Daily News, June 3, 1916, 18; “Chicago Harmony Notes,” New York Clipper, June 3, 1916, https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=NYC19160603.2.98&srpos=13&e=——-en-20–1-byDA-img-txIN-%22green+mill+gardens%22———; “At Green Mill Gardens,” Chicago Daily News, June 10, 1916, 21.

42 Don McNeill, 1942 “Breakfast Club Family Album,” Rich Samuels website, accessed June 5, 2023, https://www.richsamuels.com/nbcmm/breakfastclub/1942/walterblaufuss.html; University of Maine Digital Commons, Vocal Popular Sheet Music Collection, accessed June 5, 2023, https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mmb-vp/1825/, https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mmb-vp/1191/.

43 Advertisement, Reform Advocate, June 10, 1916, 679. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015028004888?urlappend=%3Bseq=689%3Bownerid=13510798900674363-713.

44 “At the Green Mill Gardens,” Chicago Daily News, June 17, 1916, 16.

45 “Terminate Review,” New York Clipper, July 1, 1916, 12. https://idnc.library.illinois.edu/?a=d&d=NYC19160701.2.89&srpos=15&e=——-en-20–1-byDA-img-txIN- %22green+mill+gardens%22———.

46 “Ray Raymond,” IMDb, accessed June 5, 2023, https://www.imdb.com/name/nm4912465/; “Ray Raymond,” Find a Grave, accessed June 4, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/13023/ray-raymond.

47 Advertisement, The Reform Advocate, July 15, 1916, 839. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015028004888?urlappend=%3Bseq=849%3Bownerid=13510798900674363-875.

48 Certificate of change of name, etc., August 16, 1916, Morse’s corporation papers, Secretary of State (Corporations Division): Dissolved Domestic Corporation Charters, 103/112, Illinois State Archives, Springfield.

49 Oxford English Dictionary, online version, March 2023; “Estella Harris,” Chicago Defender, September 30, 1916, 3.

50 Classified advertisement, Chicago Daily Tribune, November 1, 1916, 31.

51 Advertisements, Chicago Daily Tribune, December 9, 1916, 4; December 11, 1916, 9.

52 “News of the Players,” (Indianapolis) Freeman, December 9, 1916, 5.

53 Sylvester Russell, “Chicago Weekly Review,” (Indianapolis) Freeman, December 16, 1916, 5.

54 Chicago Daily News, November 17, 1916, 6.

55 “May Tilt the Lid,” Day Book, December 28, 1916, 29.

56 “Lid Will Be Clamped Down Tight New Year’s Eve,” Day Book, December 29, 1916, 9.

57 “Charity, Alas! Suffers by Lid New Year’s Eve,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 29, 1916, 3.

58 Day Book, February 8, 1917, 6.

59 “The Sunshine Bartender Slain,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 27, 1916.

60 Chicago Historical Homicide Project database, https://homicide.northwestern.edu/.