I went to Los Angeles. I looked for locations where some of my favorite L.A. movies were made. Especially the films of David Lynch, but others, too. Here’s what I saw and learned…

BEVERLY HILLS AND VICINITY

See an INDEX for this series of blog posts.

In this part: Greystone Mansion / Beverly Center / Franklin Canyon Park

GREYSTONE MANSION

“In heaven, everything is fine.”

As a fan of David Lynch’s films, I wanted to see the place where Eraserhead was born. But that is hardly the only claim to fame for Greystone Mansion in Beverly Hills.

This West Coast palace was built with oil money. Edward Doheny Sr., who’d discovered oil in Los Angeles in 1892, had this 55-room Tudor Revival-style home built in the late 1920s—as a gift for his son, Ned Doheny.

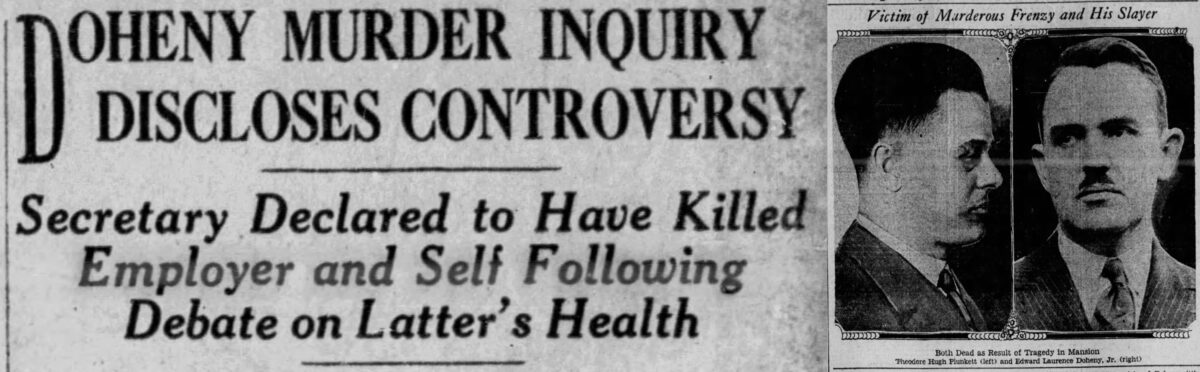

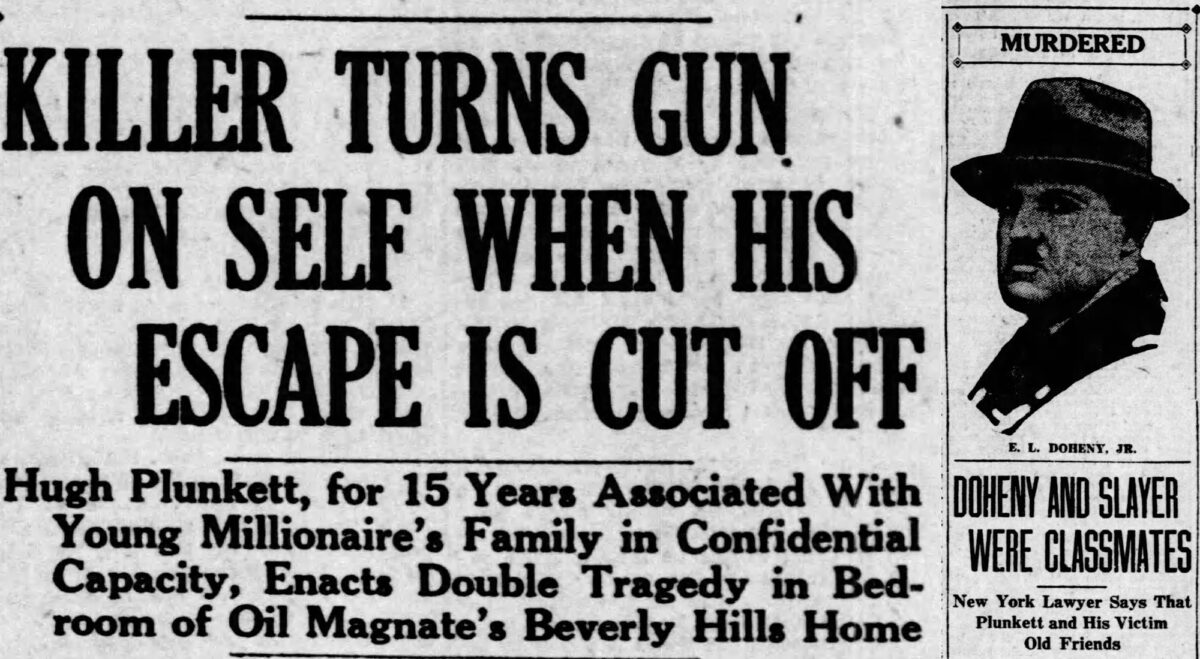

On February 16, 1929, five months after Ned and his family had moved in, he was found dead in the mansion alongside the body of his friend and aide Hugh Plunkett. Both had been shot in the head.

“After a quick investigation, authorities ruled that a deranged Plunkett shot his employer and then turned the gun on himself, but to this day the sensational crime is a source of rumor and speculation,” the Los Angeles Times wrote in 2003.

As it happened, both men were due to testify in the trial of Ned Doheny’s father in the Teapot Dome case—perhaps the biggest political scandal in U.S. history before Watergate. And Ned was accused of serving as his father’s bribery bagman.

Edward Doheny Sr. was later found not guilty of bribing an official in President Warren G. Harding’s Cabinet, even though the official was found guilty of taking the bribe.

The story of the Dohenys inspired Upton Sinclair’s novel Oil!—which Paul Thomas Anderson loosely adapted into his 2007 film There Will Be Blood, one of many, many movies filmed at Greystone Mansion.

And some scholars believe that Raymond Chandler had Greystone Mansion in mind when he described the home of General Sternwood, an aging oil tycoon, in his 1939 novel The Big Sleep (filmed in 1946 by Howard Hawks).

Greystone was later owned by Chicago industrialist Henry Crown, who leased it out for movie shoots. He planned to tear it down and subdivide the property, but Beverly Hills stopped demolition by buying the mansion in 1965.

The city leased it to the American Film Institute—and that’s where David Lynch enters the picture, arriving as an AFI student in 1970. Beginning in 1972, Lynch spent four years making Eraserhead, transforming the Greystone Mansion’s stables into a makeshift studio—creating a weird world inside its walls.

In his 2018 book Room to Dream, Lynch wrote:

“Nobody was using the stables at the AFI, so I set up there and had a pretty-good-size studio for four years. Some people from the school came down the first night of shooting and they never came down again. I was so lucky—it was like I’d died and gone to heaven.”1

For a time, Lynch even lived in the stables. “I moved into the stables when Peggy and I split up, and that was the greatest place. I’d lock myself in Henry’s room and I loved sleeping there, but eventually I had to leave …”2

The American Film Institute moved out of the mansion after 1981. Today, the grounds are a public park, Historic Doheny Greystone Estate (905 Loma Vista Drive, Beverly Hills) while the mansion itself is open only for special events.

It’s an astonishingly beautiful place. Strolling amid the buildings and gardens, I felt as if I’d somehow wandered onto the grounds of an English castle.

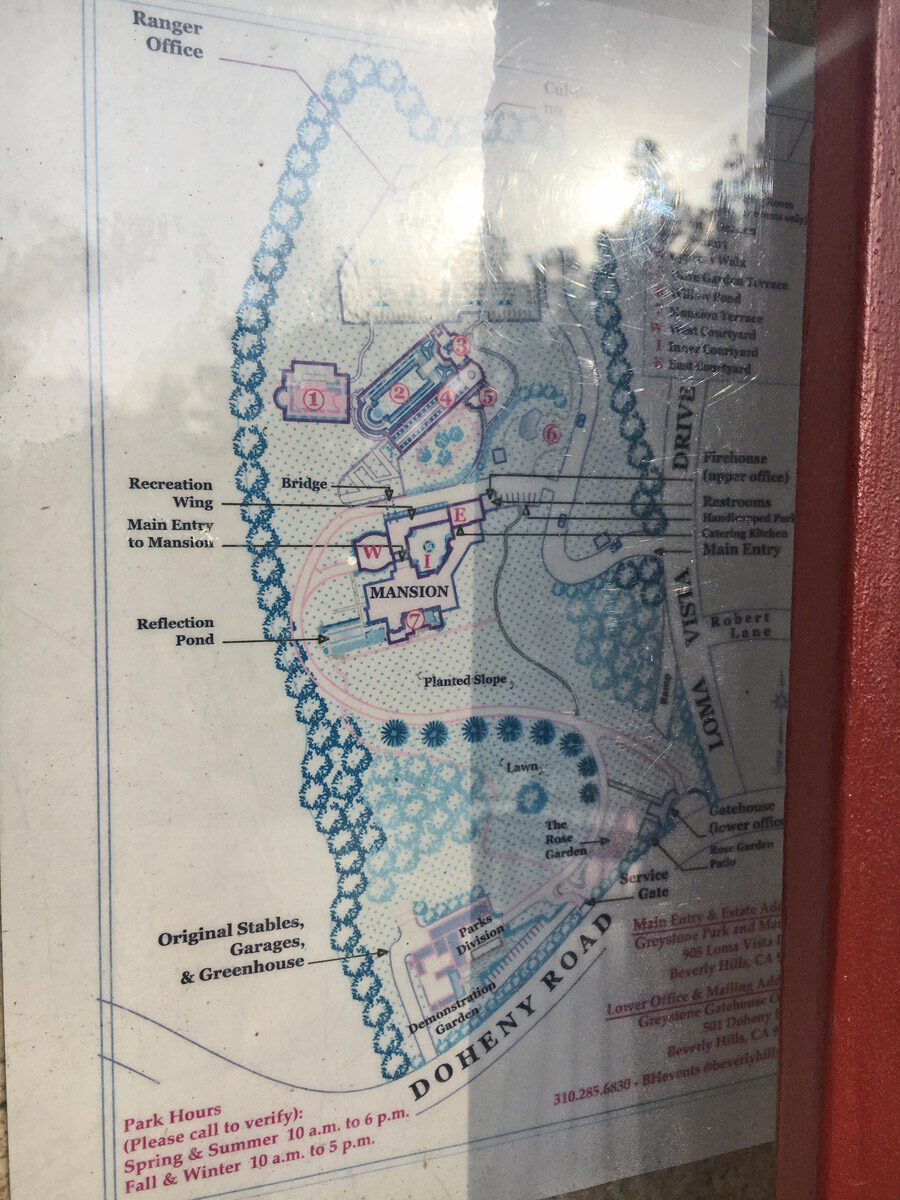

At first, it wasn’t clear to me where the stables were located, but I found a map on a placard, which showed the stables down at the southwest corner of the estate, along Doheny Road.

The gates to this section were locked, much as I’d expected. These utilitarian buildings are hardly the main attraction for most visitors, even if I think they deserve to be preserved—not only for their architectural beauty, but as a shrine to the creation of Eraserhead.

The Criterion Collection’s edition of Eraserhead includes a short film from 1997 documenting a visit by Lynch, Jack Nance, Charlotte Stewart, and Catherine Coulson to the stables. Even they weren’t allowed inside the buildings, apparently.

Until I visited this spot, I’d had trouble picturing the place where Lynch and his small team of collaborators created their surreal film, which seems so far removed from the milieu of Los Angeles. The contrast was even more striking as I stood outside the wall on Doheny Road, which is lined with tall palm trees. It’s hard to imagine how anything like Eraserhead had emerged from this sunny street lined with luxurious estates.

Greystone Mansion has a Zelig-like presence in Hollywood films and TV shows. Dozens of movies have been filmed in its rooms and gardens over the decades, including—to name just a few—Hush, Hush Sweet Charlotte, The Disorderly Orderly, The Loved One, Stripes, Ghostbusters, The Witches of Eastwick, X-Men, Spider-Man, The Prestige, and The Social Network.

In The Big Lebowski, its interiors served as the mansion of the title character (the wealthy Lebowski, of course, not the Dude). It was also Kermit the Frog’s mansion in 2011’s The Muppets.

It would be fascinating to see the scenes showing Greystone in these various films edited together, to see how the same spaces have been used time and time again. Through its numerous film roles, Greystone has become the archetype of a classic West Coast mansion.

In There Will Be Blood, it’s the mansion of oil tycoon Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis), where he proclaims, “I drink your milkshake!” That was the first film made inside the mansion’s subterranean bowling alley, located near the old laundry room where Lynch had constructed the stage for Eraserhead‘s Lady in the Radiator in the 1970s.3

In Chandler’s The Big Sleep, private detective Philip Marlowe describes departing Greystone—or a mansion similar to it, anyway:

Outside the bright gardens had a haunted look, as though small wild eyes were watching me from behind the bushes, as though the sunshine itself had a mysterious something in its light. I got into my car and drove off down the hill. What did it matter where you lay once you were dead? In a dirty sump or in a marble tower on top of a high hill? You were dead, you were sleeping the big sleep, you were not bothered by things like that.4

BEVERLY CENTER

Two miles southeast of Greystone, David Lynch filmed some outdoor scenes for Eraserhead on the land southeast of Beverly Boulevard and San Vicente Boulevard, in the Beverly Grove neighborhood of Los Angeles.

I didn’t visit this site—largely because I knew that nothing remains to be seen of the landscape Lynch filmed. Nevertheless, it’s fascinating to consider how much this place has changed.

Lynch told interviewer Chris Rodley:

“… it was one of my favorite places in the whole world. You’d go over this doughnut of earth and down inside this place, and you’d be in a completely different world. There were these oil tanks and this working oil well just standing there. It was just incredible.”

Lynch said he liked this place because it seemed frozen in time since the 1930s. “… it hadn’t changed. It was like a set. This place just existed there.”5

Back in 1931, the Ripley’s Believe It or Not cartoon had told readers about an oil well near this site:6

Beverly Park, an amusement park with a dozen kiddie rides, opened here in 1946, leasing land from the Beverly Oil Company and disguising the neighboring oil well as a dragon with flapping wings. Walt Disney’s visits to the park reportedly inspired him to create Disneyland.

(KCET reports that Alfred Hitchcock filmed 1951’s Strangers on a Train here, but that seems to be incorrect. From the American Film Institute website: “According to a Nov 1950 HR news items, the amusement park set was constructed at director Rowland V. Lee’s Ranch, which was located in the San Fernando Valley…” The Carousel Corner website agrees, noting that Hitchcock’s movie, featuring “the greatest carousel movie scene ever,” used a rental Herschell carousel.)

Beverly Park closed in 1974—around the time when Lynch filmed Eraserhead—while the adjacent Ponyland stayed open a few more years.

“Beverly Ponyland consisted of a dusty, dirty row of old wooden stalls with a 3-track riding ring where one could hear the sounds of snorting ponies, jingling bits, creaking leather saddles and sporadic ‘Giddyups,’ while the pungent mixture of hay and fresh droppings filled the air,” KCET notes.

“… After Beverly Park closed, some of the rides remained on the lot. They stood forlornly behind a chained up gate, bearing a misleading sign which read, ‘closed for renovations.'”

Lynch recalled: “There was a pony ride from the twenties or thirties. And there was this little key shop that was like four feet by four feet, with a roof. And then there was the Tail o’ the Pup hot dog stand, which has moved to another place now. And there was Hull Bros. Lumber, which was a working sawmill, I think, with a hundred-foot-tall mound of sawdust next to it. There was also a nursery. It was all, like, from the thirties—mostly dirt, with this stuff scattered around. The buildings were ancient, and guys wore those green-colored visors and armbands. They were old-timers who knew about wood and Hollywood and everything.”5

In 1979, two years after the release of Eraserhead, construction crews began building the eight-story Beverly Center shopping mall on this land. “Now it’s just like, a congestion of shops and parking and lights and signs. It’s just a huge change,” Lynch later remarked.5

In 1984, the Los Angeles Times reported that neighbors “said it was one of the ugliest buildings in the city and called it the Incredible Bulk.”7

In 1991, architecture critic Aaron Betsky wrote: “The Beverly Center is not a pretty building. It’s big, it’s brown, and it’s a blob.” He called the mall’s interior a “shining shopping nirvana” and “the Acropolis of shopping, dedicated to our national religion, consumption.”8

Since renovations were completed in 2018, the bulky shopping center is no longer brown. It “now boasts a new glimmering white skin made of a highly textured stucco surmounting a metal mesh which changes transparency through the day and according to the viewer’s vantage point.”

It’s utterly unrecognizable as the place where Lynch filmed, but oil wells are still operating on the property, concealed by the tall walls along San Vicente Boulevard.

FRANKLIN CANYON PARK

Driving north three miles from Greystone Mansion—taking Loma Vista Drive and Coldwater Canyon Drive—you’ll arrive at Franklin Canyon Park, where several scenes were filmed for Twin Peaks, especially for the second season of the TV series. This California park serves as a stand-in for the forests of Washington state in these scenes, which were mostly filmed by directors other than David Lynch.

Glastonberry Grove’s ring of sycamore trees—that portal into the Black Lodge—was reportedly filmed somewhere in these woods. So was Windom Earle’s cabin, and various forest outings by Twin Peaks characters. It’s where the show’s lawmen took a walk. And it’s where Hawk found Major Briggs. (For details about these and other places where Twin Peaks was filmed, visit location sleuth Steven Miller’s excellent Twin Peaks Blog.)

I took a short drive into Franklin Canyon Park, but alas, I didn’t have enough time to search for these locations—or the many other places where movies and TV shows were filmed. When I visited, it looked like a movie crew was filming something.

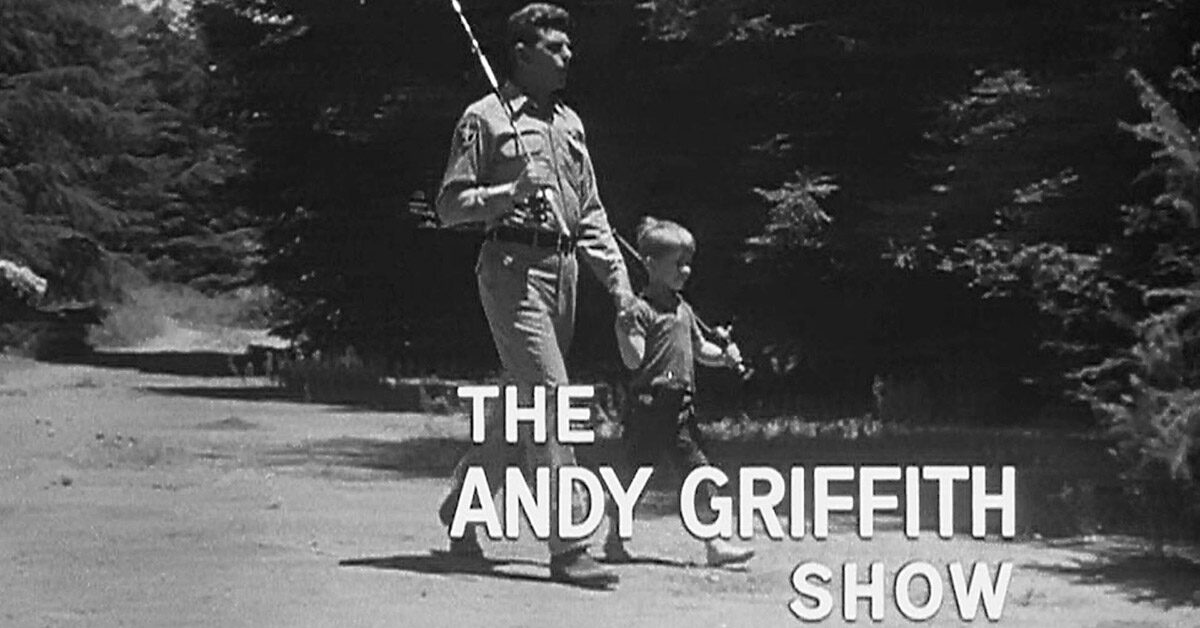

Franklin Canyon has appeared in It Happened One Night, The Blob, Minority Report, Platoon, Nightmare on Elm Street, Rambo, The Creature From the Black Lagoon, Purple Rain, and the original Star Trek TV series episode “The Paradise Syndrome.”

Perhaps most famously, a lake in the canyon serves as the backdrop for the opening credits of The Andy Griffith Show.

Franklin Canyon is also where two 1960s album covers were photographed: Simon and Garfunkel’s Sounds of Silence and the Rolling Stones’ Big Hits (High Tide and Green Grass).

This canyon is where Los Angeles Water Bureau chief William Mulholland built reservoirs and a “Mighty Siphon of Riveted Steel” from 1913 to 1916, completing a 230-mile aqueduct that carried water from the Owens Valley to Los Angeles.

Without all of that water, it’s doubtful that L.A. could have continued growing into a massive city, and the Los Angeles Times hailed this “splendid achievement by Mulholland and his assistants.”9 But people in the Owens Valley accused L.A. of stealing their water.

Mulholland was the inspiration for a character named Hollis Mulwray in Robert Towne’s screenplay for Roman Polanski’s 1974 film Chinatown. Don’t take that version of the story too literally, though.

In Los Angeles Plays Itself—a 2003 documentary that was one of the inspirations for my movie-location hunt in L.A.—director Thom Andersen observes:

“Robert Towne took an urban myth about the founding of Los Angeles on water stolen from the Owens River Valley and made it resonate,. Chinatown isn’t a docudrama; it’s a fiction. … These echoes have led many viewers to regard Chinatown not only as docudrama, but as truth, the real secret history of how Los Angeles got its water, and it has become a ruling metaphor for nonfictional critiques of Los Angeles development.”

Author David Thomson wrote that William Mulholland “is regarded now as a robber baron and ecological rapist.” But as he noted, “No one is sending the water back to the desolate Owens Valley.”10

As Mulholland was building Franklin Canyon’s reservoirs, the Dohenys—the same family that built Greystone Mansion—bought land in the lower part of the canyon for watering and grazing cattle. In 1935, the Dohenys added a Spanish adobe home in the canyon, using it as a summer retreat.

The canyon’s old reservoirs were removed from use—and one was completely drained—by the early 1980s, after officials decided they were vulnerable to earthquakes. And the land was opened to the public as Franklin Canyon Park.

The park’s north end connects with a curvy mountain highway with a famous name: Mulholland Drive.

See an INDEX for this series of blog posts.

NOTES

1 David Lynch and Kristine McKenna, Room to Dream (New York: Random House, 2018), Room to Dream, 124.

2 Room to Dream, 131.

3 Room to Dream, 122.

4 Raymond Chandler, The Big Sleep (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1939; New York: Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, 1992), 230.

5 David Lynch, ed. Chris Rodley, Lynch on Lynch (New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2005 edition), excerpted in Criterion Collection booklet for Mulholland Drive, 24.

6 Johnson City (TN) Chronicle, April 2 and 3, 1931.

7 Frank Clifford, “The Beverly Center,” Los Angeles Times, March 4, 1984.

8 Aaron Betsky, “It’s Big, Chic and Famous, but Beverly Center’s Not a Pretty Site,” Los Angeles Times, Nov. 14, 1991.

9 “Drive Great Pipe Line Through to Lower Dam,” Los Angeles Times, May 11, 1913.

10 David Thomson, “Uneasy Street,” in Sex, Death and God in L.A., ed. David Reid (New York: Pantheon, 1992), page 363 in the e-book.

Follow links in the text for additional sources.

Photos by Robert Loerzel except where noted otherwise.