This article by Robert Loerzel originally appeared in Listen magazine’s September-October 2009 issue.

When poet Carl Sandburg called Chicago “Hog Butcher for the World, Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat,” he easily could have added “Music Maker” to that list. The City of the Big Shoulders forged so many of the sounds that became popular American genres. This urban melting pot was one of the places where blues, jazz, gospel and even country music began to take shape. Today, its nightclubs and concert halls are alive with all those sounds — plus rock, folk, R&B, hip-hop, electronic and ethnic music. And despite its reputation as a “stormy, husky, brawling” town (to borrow another phrase from Sandburg), Chicago is also a sort of a paradise for classical-music aficionados.

The earliest evidence of music being performed in Chicago comes from the 1830s, when the place was just a frontier outpost. The owner of the Sauganash Hotel, Mark Beaubien, played a fiddle to entertain his guests. “He played it in such a way as to set every heel and toe in the room in active motion,” an early settler recalled. “He would lift the sluggard from his seat and set him whirling over the floor like mad!” Beaubien himself joked that his musicianship was not exactly divine. “I plays de fiddle like de debble, and I keeps hotel like hell,” the Frenchman reportedly remarked.

Chicagoans got a taste of more highbrow music in 1850, with the formation of the city’s first classical group, the Chicago Philharmonic Society, and the first local performance of an opera. Opera did not get off to a promising start in Chicago, however — the theater burned down in the middle of the second performance.

It wasn’t until 1891 that Chicago got serious about becoming a world-class musical city. That was the year a local group hired America’s most famous conductor, Theodore Thomas, to start the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. At the time, Thomas was frustrated with his post at the New York Philharmonic because of its short schedule. Asked if he would come to Chicago, Thomas quipped, “I would go to hell if they gave me a permanent orchestra.”

Thomas insisted that his new orchestra should play only what he considered the best symphonic music, even if it was music that few people understood. “Mr. Thomas is here to establish a great art work,” explained his wife, Rose Fay Thomas, “and to make Chicago one of the musical centers of the world — not to provide a series of cheap musical entertainments for the riff-raff of the public.” The “riff-raff” may not have appreciated everything that the CSO played, but the orchestra persisted, and by the middle of the twentieth century, it had earned a reputation as one of the world’s best.

Several legendary maestros have led the orchestra, including Fritz Reiner, Sir Georg Solti and Daniel Barenboim. When Barenboim stepped down as music director in 2006, critics commented on how he’d reshaped the CSO’s sound during his fifteen-year tenure. “Although it will forever be associated with Sir Georg Solti, whose memory is still cherished by Chicagoans, the orchestra that Barenboim has molded is a different beast altogether,” Michael Henderson wrote in London’s Daily Telegraph. “Whereas the brass section remains stupendous, capable of blowing down the walls of Jericho, there is a breadth, balance and color (bloom, if you like) that one did not always associate with Solti.”

Few people questioned Barenboim’s brilliance, but he sometimes seemed arrogant. As he departed Chicago, he complained about Americans treating classical music as background noise. “I can’t stand being in Chicago anymore and hearing the Brahms Violin Concerto in the elevator,” he said, “because that shows me that when they come to the concert hall they listen to it in the same way.”

After a four-year search for a replacement, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra made a stunning announcement in 2008: Acclaimed Italian conductor Riccardo Muti would be taking over as the CSO’s music director in 2010. Muti had turned down at least one job offer from the New York Philharmonic, but Chicago won him over where New York had failed.

Tempests have followed the uncompromising Muti throughout his career. In 2005, Muti ended his nineteen-year run as the music director of Milan’s La Scala after feuding with other officials at the opera house. Accused by critics of behaving like a dictator and megalomaniac, Muti quit after a no-confidence vote from La Scala employees. At the time, Muti’s wife said she doubted he would ever make music in public again. Asked later about the dispute, Muti told the Chicago Tribune, “Sometimes when the music director is very strong in demanding quality, mediocre people do not want to accept quality.”

So far, the relationship between Muti and the CSO’s musicians looks like a love affair. The raven-haired Italian adored the music that the orchestra made under his baton when he was a guest conductor in 2007. He called the CSO “a perfect machine.” That experience that persuaded Muti to sign a five-year contract as music director.

“This is one of the great musicians of our day, at the pinnacle of his artistic vision, coming together with one of the great orchestras of all time at the peak of their playing,” says Martha Gilmer, the CSO’s vice president of artistic planning and audience development. “It was incredible to experience. It truly was love at first sight.”

Explaining his decision to conduct in Chicago, Muti told The New York Times: “I have found a situation, how can I say, that has made more sweet my dry heart.”

Carl Grapentine, a longtime host on Chicago’s classical music radio station, WFMT 98.7 FM, says he can’t wait to hear what Muti will do at the helm of the CSO: “I think he’s a great combination of a stickler for precision, having a great stick technique, but also a very romantic musician.”

Muti will take over as music director a year from now, but he comes to Chicago this October to conduct eight concerts, including Brahms’ A German Requiem and symphonies by Mozart and Bruckner. Muti will be just one of three main maestros presiding at the CSO during this transitional year. Amsterdam native Bernard Haitink is finishing up his four years as principal conductor, while French composer Pierre Boulez, the CSO’s conductor emeritus, celebrates his eighty-fifth birthday in January with a month of concerts.

The CSO performs at Orchestra Hall, an auditorium designed in 1904 by Daniel H. Burnham, which received an acoustic makeover in 1997, becoming part of a larger complex known as Symphony Center. The venue also hosts jazz concerts, including Dianne Reeves, Sonny Rollins and Wynton Marsalis this season, and an eclectic series called “Symphony Center Presents,” which ranges from Emanuel Ax to Pat Metheny and Los Lobos.

The CSO is the city’s symphonic titan, but it’s just one of numerous groups playing classical music in hundreds of concerts all year round. Another giant on the scene is the Lyric Opera of Chicago, which performs at the Civic Opera House. Viewed from its west side along the Chicago River, the building looks like a huge chair — hence, its nickname, “Insull’s Throne.” Electricity baron Samuel Insull built the venue for his Chicago Civic Opera, opening the hall just a few days after the stock market crash of 1929. Like other local opera companies of the early twentieth century, Insull’s group did not last. The Lyric took over the space in 1954, when Maria Callas made her American debut in Bellini’s Norma. “She sang … like a goddess of the moon briefly descended,” Tribune critic Claudia Cassidy raved. And Chicago Sun-Times critic Felix Borowsky declared: “The city has raised an operatic voice which deserves to be heard around the world.”

Borowsky’s words proved prophetic — although keeping an opera up and running was no easy task. The Lyric’s legendary publicist, the late Danny Newman, once recalled how hard it was to persuade wealthy capitalists to donate money to the opera in its early days. “Some testy tycoons said we should either become more efficient (sell more tickets) or quietly go out of business,” Newman said. “Often they seemed morally offended when told that our product cost more to produce than we could sell it for.”

These days, the Lyric Opera boasts that its budget has been in the black for 21 of the past 22 years, including the most recent season. “First and foremost, we don’t spend more than we have,” explains William Mason, the Lyric’s general director. “And we put on a good product.”

That’s putting it mildly. Like the CSO, the Lyric Opera has been acclaimed around the world for the high caliber of its work. Does the Lyric present too much modern opera or not enough? “They have been more conservative than I would have liked,” says Wynne Delacoma, a longtime critic for the Sun-Times. “I tend to like things more adventuresome. But you realize now, they’re not facing millions of dollars in debt. So you have to say, well, it wasn’t a bad thing.” Mason says the Lyric tries to keep a good balance between popular “barn-burners” such as Tosca and modern operas — the “spikier stuff,” as he puts it. “In these challenging economic times, you’ve got to consider what you can sell.”

Another landmark of the Chicago classical world is the Ravinia Festival, in north suburban Highland Park, the summer home for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 1936. With James Conlon serving as music director and frequently conducting the CSO, Ravinia also features touring classical acts such as the Kronos Quartet and a long roster of jazz, dance, world-music and mainstream pop musicians, ranging from Tony Bennett to Elvis Costello.

Ravinia’s focal point is a pavilion with three thousand two hundred reserved seats, and the grounds also include two smaller, enclosed venues where chamber groups and cabaret singers perform. But many concertgoers prefer to sit on the lawn with blankets, picnic baskets and bottles of wines. They can’t see the stage, but they do hear symphonic sounds or pop tunes coming over the speakers.

When it opened as an amusement park in 1904, Ravinia was billed as “a place of entertainment for people of culture and refinement.” In 1929, a critic for The Chicagoan magazine wrote: “The casual visitor at the huge park … cannot fail to come under the sway of the specific magic of the place. When there is a moon it seems to do its best for Ravinia. Even the passing trains of the Northwestern hoot pianissimo.” Those same words are true today. “It’s just a little bit of heaven,” says Dorothy Andries, a critic for suburban Pioneer Press (and sister of Sun-Times critic Delacoma).

Chicago’s other great outdoor musical tradition began at the height of the Great Depression, when American Federation of Musicians president James C. Petrillo was seeking work for unemployed musicians. He persuaded the Chicago Park District to present free concerts in Grant Park in downtown Chicago. The Grant Park Music Festival was born, beginning with an ambitious series of sixty-five symphonic concerts in 1935. People of all classes and backgrounds flocked to the shows.

The Grant Park Music Festival has had many memorable moments over its seventy-five years, including a 1958 concert by Van Cliburn that marked his first American appearance after making headlines for winning the first Tchaikovsky International Piano Competition in Moscow. But Delacoma says the Petrillo Bandshell, where the Grant Park Orchestra played after 1972, left a lot to be desired. “It sounded tinny,” she says. “It sounded like it was background music from a bad radio.”

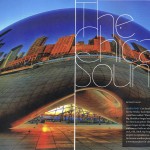

The orchestra finally got the home it deserved when Millennium Park opened at the Grant Park’s north end in 2004, unveiling the Jay Pritzker Pavilion, designed by architect Frank Gehry. Shiny metal surfaces twist and curl above the stage, and a trellis extends out over the lawn, with overhead speakers above the audience. The new book Sounds of Chicago’s Lakefront: A Celebration of the Grant Park Music Festival quotes Gehry discussing his design for the pavilion. “I pushed very hard to include the trellis to hang the speakers from so that it could create a sense of enclosure for the people on the lawn,” Gehry says. “Thanks to the trellis, people on the lawn really have a sense of a coherent space.”

The sound is wonderful, and concertgoers also get a breathtaking view of the Chicago skyline. The Grant Park Orchestra, led by principal conductor Carlos Kalmar, is flourishing in the new space, playing music that tends to be a little more daring than the summer fare at Ravinia. “The orchestra was ready to have its profile raised,” Delacoma says. “It’s been absolutely stunning.” The concerts are still free, although Grant Park Orchestra subscribers get first priority on the seats nearest the stage. The Pritzker Pavilion also hosts world music, indie-rock and a chamber music series called “Dusk Variations.”

Arguably as important as the Pritzker, another venue opened just to the north in 2003 — the Harris Theater for Music and Dance. With fifteen hundred twenty-five seats, this nonprofit theater is the right size to host concerts by groups that don’t have as big of a following as the CSO or the Lyric Opera. It’s now the regular home for Chicago Opera Theater, Music of the Baroque, Hubbard Street Dance Chicago and local avant-garde ensemble eighth blackbird. The 2009-10 season also includes Mikhail Baryshnikov, Lang Lang and a Q&A with Stephen Sondheim. And the Harris hosts the CSO’s MusicNOW contemporary series — more of that “spiky stuff” that probably wouldn’t fill enough seats over at Orchestra Hall.

Chicago’s classical music scene has burgeoned in recent decades, with a growing number of small and medium-size organizations. Other notable examples are the Chicago Sinfonietta, the Newberry Consort and Bella Voce. Orchestras are also based in several suburbs, including Elgin, Lake Forest, Evanston, Northbrook, Elmhurst, Oak Park-River Forest, Skokie and Highland Park, just to name a few. And Chicago is home of the Joffrey Ballet, which performs at the Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University. “There are just so many groups in town,” WFMT’s Grapentine says. “Not enough time to hear them all.”

And Chicago has many venues. Northwestern University in Evanston, the University of Chicago, Dominican University and other colleges present top-notch concerts featuring both local and touring musicians. The Music Institute of Chicago has a superb venue in Evanston. The Museum of Contemporary Art hosts concerts on the avant-garde end of the spectrum, including upcoming appearances by Philip Glass and International Contemporary Ensemble. The Chicago Cultural Center also presents concerts, including showcases for young musicians.

On top of all that, classical and avant-garde influences are seeping into many of the rock and jazz shows at clubs like the Empty Bottle, Schubas and the Hideout, where it’s common to see cellos, violins and trumpets mixing with electric guitars.

Critic Dorothy Andries says Chicago has classical music for all tastes. “You can look around and you can find what you want,” she says. “I really believe in Chicago.”