This article by Robert Loerzel originally appeared in Playbill magazine in September 2009.

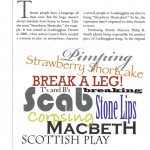

Theater people have a language all their own. But the lingo doesn’t always translate from house to house. Take the term “Strawberry Shortcake,” for example. It was coined at Lookingglass Theatre in 2001, when the actress Lauren Hirte needed a costume to play an anonymous character in a crowd scene during the company’s adaptation of Charles Dickens’ Hard Times. When she donned a frilly Victorian outfit with a big bonnet, her resemblance to the cartoon character Strawberry Shortcake left her castmates in stitches. Now, whenever an actor or crew member puts on a special costume to portray a nameless person in a crowd, people at Lookingglass say they’re being “Strawberry Shortcaked.” So far, the expression hasn’t migrated to other theaters in town.

Producing Artistic Director Philip R. Smith admits being responsible for another piece of Lookingglas slang. In the original production of Mary Zimmerman’s Arabian Nights, Smith played the sheik who describes how hideous his daughter looks. One night, Smith blanked out on an entire paragraph of dialogue and the only part he could remember was the word “scab.” So he blurted out, “She’s … scab!” As a result, if Lookingglass actors forget their lines, colleagues will say, “You scabbed it.” (A more widespread expression for this is “to go up on your lines.”)

“Pimping” is a word you’ll hear around Chicago’s Second City. It’s what happens when one performer tries to embarrass another actor onstage. Let’s say an actor is a terrible singer. In the middle of an improvised sketch, a castmate might say: “Oh, I heard you were a great singer. Why don’t do you that opera song you were talking about?” A little bit of “pimping” can be humorous, but it’s discouraged by Matt Hovde, director of Second City e.t.c.’s show, Studs Terkel’s Not Working. “Usually, it’s just seen in good fun, but sometimes, people get real upset,” he says. “That’s a habit we try to break early on.”

The last line in a Second City scene is known as the “button,” “tag,” “out” or “blow.” The beginnings and ends of scenes are “T’s and B’s,” an abbreviation for “tops and bottoms” (British and Canadian comics call them “tops and tails”). When comedians start laughing in the middle of a scene, Chicagoans say they’re “breaking,” but Canadian improvisers call it “corpsing.”

Bill Osetek, artistic director at Drury Lane Oakbrook Terrace, says he witnessed a new piece of slang being coined at his theater. After a substitute musician hit a bad note one night in the orchestra pit, the stage manager remarked, “Why do they send us ‘Stone Lips’ as a sub?” Now, whenever a musician at Drury Lane hits the wrong note, people say, “Stone Lips is back.”

Some of the older theater slang is rooted in superstitions. It’s supposedly bad luck to wish an actor good luck. So instead, one says, “Break a leg!” There are many theories about where this tradition comes from. One suggests that “break a leg” is an old-fashioned way of describing actors bending their knees to acknowledge applause. Or maybe it describes an audience stomping its feet to show approval. It might simply be a case of reverse psychology: Say something bad to mean something good.

It’s also bad luck to say “Macbeth” when you’re inside a theater—apparently because early productions of the Shakespeare tragedy experienced so many accidents that the play itself seemed to be cursed. Instead of saying the title, theater folk call it “the Scottish play.” Jonathan Weir, an Oak Park actor who plays several characters in Jersey Boys, even sounded nervous when he uttered the name of the Bard’s play during a phone call. “Thank God I’m not in a theater now,” he said. If someone makes the mistake of saying “Macbeth,” there is a way of nullifying the curse. “Go outside and close the door, turn around three times,” Weir suggests. “Spit, and then swear. And then ask to be let back in. That’s supposed to break the curse.” It sounds rather silly, but Weir says many actors are dead serious about this “Scottish play” business.

Like a lot of slang expressions, “the Scottish play” and “break a leg” have persisted for a long time. Their exact origins are shrouded in the fog of history, but people still say the words anyway. And who knows? If “Stone Lips,” “scab” and “Strawberry Shortcake” catch on, scholars a hundred years from now may well find themselves debating the origin of these strange, Chicago-born expressions.