This article by Robert Loerzel originally appeared in Pioneer Press on March 22, 2007.

Editor’s note: In 1993, Pioneer Press reporter Robert Loerzel was one of the first reporters on the scene of the Brown’s Chicken murders in Palatine and has followed the case closely ever since, ncluding the upcoming trial of suspected killer Juan Luna. Loerzel returns to Pioneer Press as a correspondent to give his insight into how those murders and the potential resolution of the case have weighed on the community for more than a decade.

People stood for hours in the snowy parking lot outside Brown’s Chicken on Jan. 9, 1993, waiting for answers.

Even if they dreaded what they would find out, everyone wanted to know what had happened inside Brown’s the night before: Who had killed the Palatine restaurant’s two owners and five of its employees? And why?

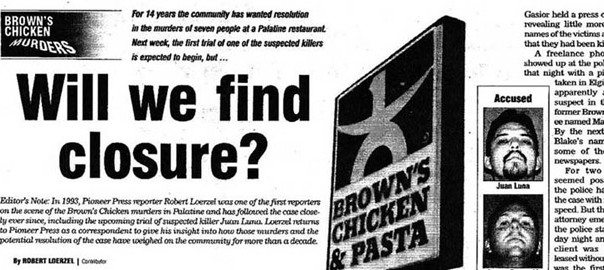

Nine years went by before police announced they could answer that first question. In 2002, Palatine police charged Juan Luna and James Degorski with the murders.

Then another four years went by. The justice system slowly laid the groundwork for Luna and Degorski to stand trial.

The wait for justice is finally nearing an end of sorts, although a long process still lies ahead. With the two men facing separate trials, jury selection begins Wednesday in Luna’s trial.

All of those people who gathered so long ago in that parking lot may finally hear some answers to the questions that have been haunting them for 14 years.

* * *

Cars were still parked outside the restaurant in the snow that morning – cars belonging to employees who should have gone home the night before.

Yellow crime-scene tape cordoned off that corner of the parking lot – the area immediately around Brown’s — from the rest of the shopping center. Police cars were parked at each of the building’s corners.

Snow was stuck on the yellow letters on the green roof, which spelled out “BROWN’S CHICKEN.” Motorists passing by on Northwest Highway slowed down and looked over.

The news had been on the radio that morning, a sketchy report based on the sketchy press release faxed to the media at 7:15 a.m., which revealed little beyond its opening words: “The Palatine Police Department is investigating a multiple homicide at the Brown’s Chicken Restaurant…” A photographer for Pioneer Press had heard the news and called me at home.

White vans with television-news logos were parked in the shopping center, their antennas aimed skyward. The rest of the parking lot was full, as customers came and went from the strip mall’s other shops, trying to go about their business as normal.

Clusters of people stood around the lot. I recognized a couple of them as employees who had taken my orders when I’d eaten at Brown’s. Some of them were friends of employees. Some were people who lived nearby.

A woman began sobbing when she saw her friend’s car parked outside the Brown’s. She hugged a friend and they slowly walked away, photographers snapping their pictures as they went.

Palatine Mayor Rita Mullins was there for a while, noting in a statement a couple of days later: “I spent several hours in the parking lot outside of Brown’s that Saturday, standing alongside family members, friends, other employees, shivering both from the cold and from the overwhelming enormity of what had happened. I would have gladly given all that I have to have changed the news that came in the early hours of that morning.”

It was impossible to see anything happening inside the restaurant. Once in a while, investigators could be seen going in and out of the doors. They put plastic bags over their feet as they entered.

By the time night fell, and the bodies were finally carried out on sheet-covered stretchers, I was over at the Palatine Community Center with another crowd of reporters. Like me, they were frustrated at hearing “no comment” all day. Deputy Police Chief Walt Gasior held a press conference, revealing little more than the names of the victims and the fact that they had been killed.

A freelance photographer showed up at the police station that night with a picture he’d taken in Elgin as police apparently arrested a suspect in the case, a former Brown’s employee named Martin Blake. By the next morning, Blake’s name was in some of the Sunday newspapers.

For two days, it seemed possible that the police had cracked the case with impressive speed. But then Blake’s attorney emerged from the police station Monday night and said his client was being released without charge. It was the first of many false leads.

Even without knowing anything about the seven people who’d been murdered, the crime seemed too horrible to imagine. But as we learned more that week about the victims — a couple of entrepreneurs, some high-school kids, immigrants, all of them hard workers just trying to make a living — the senselessness of the crime became painfully evident.

Five days after the murders were discovered, Palatine’s Cutting Hall hosted a memorial service for the community. I’m not religious, and I was supposed to be there in my role as an objective observer, but I cried a little as the crowd sang “How Great Thou Art,” a familiar hymn that includes the lines: “And when I think that God, His Son not sparing, Sent Him to die, I scarce can take it in.”

* * *

From the first day of the Brown’s case, the relationship between the Palatine police and the media was contentious.

When I visited Police Chief Jerry Bratcher a month after the murders — for an interview at the temporary headquarters the police had set up in the former School District 15 building on Quentin Road, currently the home of the Palatine Township Senior Center — I sensed a bunker mentality.

Bratcher and other officials were on the defensive, saying they’d done everything they could to solve the murders, including calling in assistance from the FBI, the Cook County State’s Attorney, a crime lab and other police departments. The police acknowledged a few missteps — one of the most undeniable errors was the bungled response to the first reports that a Brown’s employee hadn’t returned home — but insisted none of the mistakes had made any difference in solving the crime.

In interviews over the next several years, Bratcher and Deputy Chief Jack McGregor said over and over that they wished they could say more. But they revealed only a few carefully chosen details about the investigation, sticking for the most part with vague, general statements. They did their best to exude confidence that they would eventually catch the murderers, while venting frustration at all of the second-guessing in the media.

In January 1994, Bratcher said, “We’ve had cases that have gone on for years that have been solved. This case will be solved.”

It was understandable why the police were being so cautious about releasing information. Some details of the crime had to remain secret. When they interrogated suspects, detectives needed to see if the suspects knew things about the crime that they couldn’t have learned from the news. That’s standard procedure.

But police also need to release details that might bring citizens forward with tips, and at times it seemed like no one had anything to go on — other than the information leaking out from certain members of the investigative task force to certain members of the media.

Some of those stories from anonymous sources focused on leads that the police had supposedly botched. In 1995, reports on NBC-Channel 5 and ABC-Channel 7 made it appear that the police had blown their investigation of “Lead 80,” the theory that a jailed gang member was responsible for the murderers. Police insisted they had thoroughly checked out that lead, and it was a dead end.

Meanwhile, every time a crime remotely resembling the Brown’s killings happened anywhere in the country, it prompted speculation that there might be a connection.

Several times, the police — and the media — zeroed in on possible Brown’s suspects, but each of these leads fizzled.

Ten days after the Brown’s murder, a beheaded corpse had been found on a railroad embankment in Barrington. Later that spring, Paul Modrowski and Robert Faraci were charged in the killing, and the body was identified as Dean Fawcett. Faraci reportedly told interrogators that Modrowski had committed the Brown’s murders as well, but the story never resulted in solid evidence or any charges.

Modrowski was convicted in the Fawcett murder, while Faraci was acquitted. Years after that angle on the Brown’s case seemed to have gone cold, the police were apparently still interested – asking the two men to submit DNA samples in 2000.

Another suspect, a resident of Chicago’s West Side whose attorney said he had never even been to Palatine, was hauled into the police station when it appeared his fingerprints matched a print found at Brown’s. One police official told me that the match was “golden.” But it turned out to be a mismatch, and the man was released without being charged.

On the third anniversary of the murders, police finally decided to reveal a little more about the crime — describing a Nike Air Force shoe print found at the crime scene, and disclosing that a .38 or .357-caliber revolver that was used to kill all seven people.

They also confirmed some information that had previously been leaked — that a meal had been purchased at Brown’s at 9:08 p.m., eight minutes after the restaurant should have closed for business. Then the power to the clock was shut off at 9:48 p.m. The murders, police said, had happened during those 90 minutes.

Over the years, local residents occasionally called me with their own tips and theories, involving drug dealers, psychopaths, conspiracies and confessions. The stories were always too vague to pursue.

The criticisms against the Palatine Police Department came to a boil on Nov. 20, 1997, when the Better Government Association released a report called “Patent Malarkey: Public Dishonesty and Deception.”

The report criticized the Palatine police for waiting too long to call in assistance from other departments and for focusing most of their resources on Martin Blake during the first days of the case. The BGA slammed Bratcher for cronyism and his detectives for its inexperience and incompetence. As far as the BGA was concerted, Exhibit A was that infamous “Lead 80.”

Not surprisingly, police officials disputed these accusations. They insisted again that Lead 80 amounted to nothing. And then in 2000, the Illinois State Crime Commission released its own report on the BGA report, finding: “In short, the Better Government Association’s report’s conclusions are not based upon fact.”

The problem with both reports is that the people writing them did not have access to the thousands of pages of evidence that police had collected in the Brown’s case.

It’s a Catch-22. If public officials do a bad job of investigating a major crime, they should be held accountable for it. But if the investigation is still under way and most of the details understandably remain secret, it’s difficult for any outside observer to really know what sort of job the police are doing.

People often asked me if I thought the Brown’s case would ever be solved. Yes, I would say. The killers will make a mistake eventually. They’ll be arrested for something else, and they’ll confess or their fingerprints will match a print found at Brown’s. Or they’ll blab to someone, and that person will go to the police. But until something like that happens, it’s a waiting game.

* * *

Palatine police finally had a breakthrough in the Brown’s case in April 2000. The Illinois State Police Forensic Science Center said it was using a new kind of DNA test on evidence from the restaurant — reportedly the partially eaten chicken dinner that had been purchased at 9:08 p.m., presumably by one of the killers. Investigators had preserved the remains of that fast-food dinner in 1993, even though no DNA tests at the time were capable of analyzing the human saliva on the chicken.

By 2000, Bratcher had retired and McGregor was the police chief. The Brown’s investigative task force, which had included a hundred people in the days right after the murders, was down to three detectives still working full-time on the case. “It ebbs and flows,” McGregor said.

On April 28, 2001, the building that had once been the Brown’s Chicken was finally demolished. After the restaurant closed, it had been converted into a dry cleaner’s. After that business failed, remodeling began to transform the structure into an Italian restaurant, but that venture stalled.

On the day it was torn down to make way for parking spaces, Mary Jane Crow, sister of Brown’s victim Michael Castro, asked for a pause in the demolition. She threw a brick through a window and broke down in tears.

Getting rid of the building removed the most obvious reminder of the Brown’s case, but it still felt to me like a dark cloud was hanging over Palatine. Whether you knew one of the victims or were just someone who lived in the neighborhood, it was hard not to wonder what had happened and when the case would ever be solved.

And then, after 4,841 other tips, the police received a call in March 2002. A woman named Anne Lockett told the police that James Degorski, who had been her boyfriend in 1993, and his friend, Juan Luna, had confessed to her back then that they were the Brown’s killers.

This might have been just another story, except that Lockett mentioned something about the crime that the police had managed to keep secret for all those years. “(Lockett) remembered them saying that one of the younger guys that they shot in the cooler threw up his french fries,” Assistant State’s Attorney Linas Kelecius said in 2002.

“It was something we never released,” said Detective Sgt. Bill King, the only investigator who’d worked on the case since the beginning. “That became very interesting to me right away.”

The police allegedly found another witness, Eileen Bakalla, who also said Degorski and Luna had confessed to her. Degorski allegedly told her, “We did something big.” Authorities said Lockett and Bakalla waited nine years to come forward because they were afraid.

Luna was 18 at the time of the murders, and Degorski was 20. Both of them allegedly said during their confessions that their motive was robbery, but authorities raised the possibility that they were thrill-seekers who killed for the sake of killing.

Police say Luna’s DNA matched the saliva found on that last chicken dinner at Brown’s – evidence that Luna’s attorney is now contesting. Police had briefly interviewed Luna, a former Brown’s employee, in 1993. Now they questioned him again, and Luna confessed to the murders during a videotaped interrogation, according to authorities. They say Degorski also confessed, though not on videotape.

John Koziol — a detective in the early days of the case, who had succeeded McGregor now as chief — stepped up to a podium at Village Hall on May 18, 2002, to announce Luna and Degorski had been charged with the Brown’s murders.

It felt strange to look around the room and recognize faces from nine years earlier, all who’d been waiting for this day.

Visibly angry, Koziol said, “To the people now charged: You wanted to do ‘something big.’ I hope you are placed in a cage, that you have built through your own inhumanity toward the innocent. I am confident that you will receive the death sentence you so justly deserve. It galls me that these two individuals, who are void of human conscience, took the lives of seven decent, law-abiding Americans. May those seven people, whose faces will forever be etched in our memory, now rest in peace.”

The arrests seemed to vindicate the police. If the information presented by the police is true, then it’s hard to see how detectives could have found Degorski and Luna any faster than they did.

But what will the trials reveal about the way police had handled the case?

If Luna and Degorski are found guilty — and if the verdicts hold up after the inevitable appeals, which could drag out the process for many more years — the question of “who?” will be answered.

If they’re found not guilty, the mystery may become even more muddled than it had been before.

And even guilty verdicts may not offer a definitive answer to the more profound question, “why?” Criminal trials give us glimpses into the reasons why people commit crimes, but those glimpses often raise more questions than they answer.

Closure may be a long way off.

Postscript: In 2007, Juan Luna was convicted of the Brown’s Chicken murders. Two years later, James Degorski was convicted of the murders in a separate trial. Both men received life sentences in prison.