This article by Robert Loerzel originally appeared in Pioneer Press on March 1, 2007.

Once upon a time, a brash young rock band from England descended on Chicago’s northwest suburbs, smashing guitars and making a loud and rebellious racket. Forty years later, fans vividly remember when The Who came to town.

The surviving members of The Who, Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend, will play Monday at the Sears Centre in Hoffman Estates, but this arena concert isn’t likely to be quite as raucous as their explosive shows of the 1960s, when they sang, “I hope I die before I get old” — and still meant it.

The Who’s earliest U.S. concerts included a June 15, 1967, stop at the Cellar in Arlington Heights and a July 31, 1968, show at the New Place between Cary and Crystal Lake.

Paul Sampson, now a Crystal Lake resident, owned the Cellar, a teen club at the corner of Salem and Davis streets that hosted concerts by Chicago bands such as the Shadows of Knight as well as touring acts like Cream. The building is now an auto repair shop, not far from the Arlington Heights Post Office.

“The most distinct thing that I remember about The Who was Peter Townshend coming to my office,” Sampson said. “(Townshend) says, ‘I can’t go on. I’ve got guitar-string problems.’”

Sampson recalls thinking that Townshend was “a little spoiled,” a quality common in that era’s rock stars.

“I thought, ‘Give me a break,’” Sampson said. “Needless to say, I let him know that he wouldn’t be paid if he didn’t go on. It just doesn’t work that way. I guess he found it within himself to go out and take care of whatever the issues were.”

John Sennett, who now lives in Schaumburg, was a 13-year-old Arlington Heights kid when he went to see The Who that night.

“I had all their albums, including their monumental first, ‘My Generation,’” Sennett said. “My brother Michael was in a band called the Reejuns. They played some of The Who songs, so I was quite in touch with The Who. They were very ‘tough’ at the time. A street band, singing songs of the street, of the youth.”

A critic for the Chicago Tribune noted that the Thursday night concert got started late, after 20 minutes of “electronic troubles.” The Who ended up playing for only 15 minutes, the newspaper reported, “but it was sweet and loud.”

Sampson doubts the concert was that short. “No, no, I do not recall that,” he said. “I’m pretty sure if they had gone on for 15 minutes, there would have been reservations at the end. … Generally, when a group came in, they were contracted for 45 minutes. The total onstage routine … had to be close to that.”

Kirby Bivans, an Evanston musician in a band called the Other Half, was in the audience. Answering questions by e-mail from his current home in Switzerland, he recalled: “Pete Townshend was having problems with his amplifier and they had a little roadie who was scurrying back and forth behind the amplifiers to try to fix the problem. Pete’s solution was to ram his guitar neck into the amplifiers and sometimes he would knock them over, causing the roadie to cover his head and tried to get away; it was both shocking and comical. We would see the roadie run back to the front of the building and get another amplifier top and bring it back and connect it, only to have it malfunction again causing Pete to ram his guitar neck one more time into it. And sometimes Pete would just throw his guitar neck as high as he could and it would get caught in the chicken wire, which was only about three feet above his head. That would cause him to get really angry and he started pulling it down.”

Sennett said the Cellar’s acoustics basically consisted of noise echoing off concrete walls. “That’s the way we liked it,” he said. “Hard guitar chords and tough vocals along the tracks, in a warehouse.”

He saw Sampson looking through the glass window of the Cellar’s control booth, which was above the crowd. Sennett remembers Sampson looking “elated.”

“They were really loud,” Sampson said. “It was ‘bang, crash, bang, crash.’ It was a bit of smasheroo-type thing. I don’t know how much musical value one got out of that, but it became one heck of an act. That’s what they were famous for.”

Sennett remembers “bass and drums pounding till the walls shook.”

As The Who finished their set, as Townshend smashed his guitar. “Their last song was ‘My Generation’ of course, and during the song the little roadie lit some smoke bombs and we all started choking,” Bivans said. “Someone opened the fire doors and we all tried to get out as fast as we could, along with The Who. The band jumped into a waiting black Cadillac limousine and drove away as fast as they could.

“After the show, the guitar player in my band came up to me, and I said to him, ‘I just ran into Keith Moon.’ He said, ‘Far out! Did he say anything to you?’ I said, ‘No I really ran into him; he almost knocked me over trying to get out!’”

Sennett said the experience of seeing The Who at the Cellar had a lasting impact on him.

“Their pounding chords and disruptive nature drove my personality throughout my youth,” he said. “Playing in a small venue like the Cellar made The Who one of us — no different, except they knew how to play excellent, earth-shattering music.”

Paul Wertico, an acclaimed jazz drummer who lives in Skokie, was a student at Cary-Grove High School when The Who came back to the area for another concert in July 1968.

The Who played in the courtyard of a small club called the New Place, which was in an unincorporated area between Cary and Crystal Lake, on Route 31 less than a mile south of Northwest Highway. After the opening bands finished playing, the audience waited, anxiously wondering where The Who were. Their equipment was onstage, but there was no sign of the band.

“I was standing maybe three feet from the stage, and all of a sudden, a helicopter lands in back of the fence, and they hop over the fence,” Wertico said. “There was a mad crush to the front of the stage.”

Recalling The Who’s famous personas, Wertico said, “I remember Entwistle being really staid and just looking out. He was watching Keith and he was really playing.

“The other three guys were going completely ape,” he said. “Roger Daltrey’s twirling the microphone. He’s got tape on the microphone so it doesn’t fall off. And Townshend’s doing all those windmills.

“Keith broke so many drumsticks. We were wondering if they were broke to begin with, because it was so ridiculous the number of sticks he broke during that performance.”

The Who were so loud that they knocked out the power seven times that night, and each time, Moon continued drumming as the electricity went out. Then came the crushing finale.

“All of a sudden, Townshend put his guitar through one of the high-watt amplifiers,” Wertico said. “And Daltrey’s doing the same thing, taking his mike stand and destroying stuff.

“Part of Pete Townshend’s guitar landed right in front of me, and this big guy who worked for The Who just jumped and grabbed it. It was so exciting, it was just unbelievable.”

The show left a big impression on Wertico.

“The thing that blew my mind was they went through that whole thing of trashing their equipment in a place like that,” he said. “That’s amazing to me. You’d think they’d just save that for the big shows. They did not go on autopilot. They could have been playing for a million people that night.

“It was stunning, the amount of energy and the amount of joy,” Wertico added. “That’s what made me want to be a musician.”

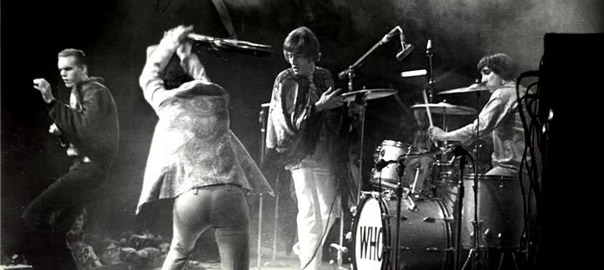

Photo: The Who at Monterrey