This article by Robert Loerzel originally appeared in Playbill magazine in 2014.

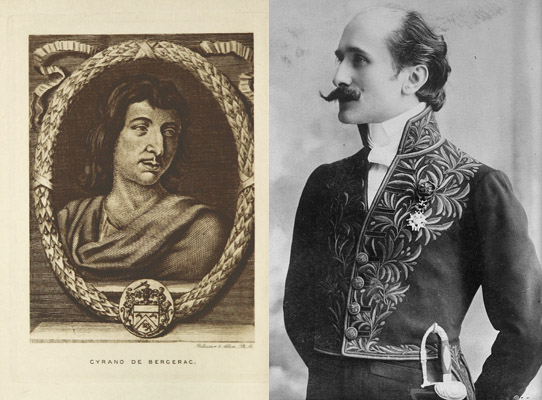

In 1902, Parisians laughed whenever they heard the name “Chicago.” In cafes, they joked about that city in America where some judge had just ruled that the popular French play Cyrano de Bergerac was a work of plagiarism. Incroyable! And even more unbelievable, that American judge said French playwright Edmond Rostond had stolen his smash-hit romance from … a Chicago real-estate developer? Sacre bleu! How could such an outlandish allegation be true? “It must be April Fool’s Day in Chicago,” world-famous French actress Sarah Bernhardt sniffed in disbelief.

But it was no joke. A federal court official in Chicago had indeed compared Rostand’s 1897 play with a more obscure script—The Merchant Prince of Cornville by Samuel Eberly Gross. Sure, it seemed unlikely that one of France’s most respected authors would lift major plot points from a virtually unknown book by a real-estate tycoon who’d built more than 10,000 working-class houses in Chicago and the suburbs. But that’s exactly what the court decided. There were dozens of similarities between the two plays. Cyrano was “a clear and unmistakable piracy,” the official concluded.

Both plays were about one man who writes love letters and speeches to help another man win a woman’s heart—even though the man writing the letters is just as much in love with her. In both plays, the woman stands on a balcony as the two men try to woo her from below. Both plays have literary duels using wordplay instead of swordplay. Both have key characters named Hercules. And big noses feature prominently in both.

Gross decided to sue when he saw the Chicago premiere of Cyrano in 1898. He’d written his own play back in the 1870s. Gross had shopped around his script, but no one was interested. He tried again in 1896, publishing 250 leather-bound copies. The Merchant Prince of Cornville finally made its premiere at a London theater that year, but was quickly forgotten.

“I never heard of Mr. Gross nor his comedy until he began action against me,” Rostand insisted in a deposition, testifying in Paris as part of the legal proceedings in Chicago. Rostand also pointed out that Cyrano de Bergerac was an actual person who’d lived in France in the 1600s. Rostand said he’d based his play on real history.

The court found no proof that Rostand had read Gross’ book, but it was at least possible he’d seen it. Gross had given his script to theatrical producers in Paris, including the French actor Benoît-Constant Coquelin—who later starred in Cyrano de Bergerac. Was that just a coincidence? “There’s a man named Gross—bah!—in Chicago, who says Rostand stole Cyrano from his play,” Coquelin said. “It’s ridiculous. The fellow is ridiculous.”

Judge Christian Kohlsaat rewarded a mere $1 to Gross, but his ruling effectively halted U.S. productions of Rostand’s play for years to come. “Cyrano shall not be played without my permission,” Gross said. Over in France, Rostand ridiculed the Chicago court ruling. “I am ready to admit I took … all our 17th-century history from Eberly Gross of Chicago,” he jested.

“You see, there is no answer there—nothing but an attempt at sarcasm,” Gross replied. “That’s the trouble with the French—you present an argument and they reply with a shrug of the shoulders. All they can say is that I did not write that because I am an American. … I have won a fight for the American people.”

But Gross’ triumph did not last. Learned Hand, a federal judge in New York who later became famous as a Supreme Court justice, issued his own ruling in 1920. Hand said the two plays weren’t actually all that similar—and The Merchant Prince of Cornville was a bad piece of writing. Would Rostand have imitated Gross? “Highly improbable,” Hand declared, opening the door for American theaters to bring Cyrano de Bergerac back onto the stage.

By that time, both Gross and Rostand had died. Cyrano de Bergerac has endured as a beloved romance, inspiring more than a dozen movies, including 1987’s Roxanne, starring Steve Martin. Meanwhile, The Merchant Prince of Cornville fell even deeper into obscurity. It has rarely, if ever, been performed. That doesn’t settle the question of plagiarism, but history’s verdict on the quality of the plays is clear. Victory, Cyrano.