This article by Robert Loerzel originally appeared in Listen magazine’s summer 2011 issue.

The concert hall was packed with thousands of young women. As they heard the music rising from the stage, they seemed to sigh in unison. Some of their faces turned pale. Some blushed, as if overcome with emotion. Their mouths twitched and their eyes sparkled. They swayed back and forth. Some of them sobbed. They called out at the musician commanding their attention, a young man with a floppy mop of curly blond hair. “Divine!” they exclaimed. “Adorable!” And as the concert ended, they leapt to their feet, applauding and shouting hysterically, demanding one encore after another.

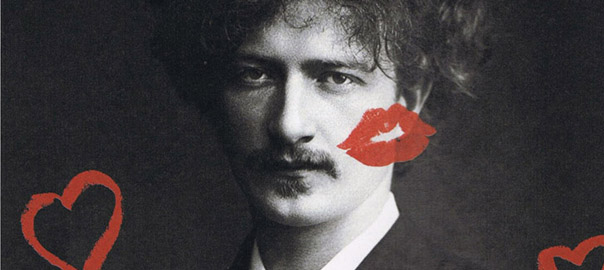

It was the 1890s, and the object of all this adoration was the virtuoso Polish pianist-composer Ignacy Jan Paderewski. This was decades before pop stars like the Beatles, Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra whipped audiences into a similar frenzy. It was more than a century before teen and pre-teen audiences went wild for far less innovative or talented performers like Justin Bieber and Miley Cyrus. Back in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the stars who inspired this sort of mania were classical musicians and opera singers.

The phenomenon of crazed concertgoers goes back at least as far as the Italian violinist-composer Niccolo Paganini, who began playing solo concerts in 1809 and amazed audiences with his speedy fingering. “The Italians … applaud him like mad, and when he leaves the theatre, three hundred people follow him to his hotel,” one writer of the time observed. Some believed Paganini had to be in league with the devil to play so well. According to biographer John Sugden, “Paganini’s audiences in these early years were for the most part uneducated in the purer forms of musical taste, uninhibited in their response to performers, and eager to indulge a new star; the symptoms are familiar to us in the age of modern ‘pop’ music.”

In 1832, Franz Liszt attended a concert by Paganini and decided he would strive to become just as virtuosic on the piano as Paganini was on the violin. By 1842, Europe was caught up in a fever called “Lisztomania.” The pianist-composer seemed to put his audiences into a sort of trance. His public concerts were “packed, noisy, at times almost riotous affairs,” writes historian and pianist Kenneth Hamilton in After the Golden Age: Romantic Pianism and Modern Performance (Oxford University Press, 2008).

“In Liszt’s day, outbursts weren’t just allowed, but expected,” Hamilton writes from the University of Birmingham in England, where he is a music professor. “You would shout ‘bravo’ at any passage you liked the sound of, and might even request that it be repeated!” Of course, no recordings exist of Liszt, but written accounts suggest that he was pretty phenomenal. Liszt himself later acknowledged that he’d pandered to audiences in his early years by playing virtuosic runs of notes that would impress people — even if that meant making up passages that weren’t in the original compositions. “In my arrogance I even went so far as to add a host of rapid runs and cadenzas, which, by securing ignorant applause for me, sent me off in the wrong direction,” Liszt wrote.

Women at Liszt concerts grabbed his silk handkerchiefs and velvet gloves as souvenirs — clearly, his appeal was not just musical. “Liszt seemed to have had the ultimate in personal magnetism,” Hamilton says. “Even those who hated his music were captivated by his appearance and personality. When you add together Liszt’s astonishing keyboard mastery with his looks and love of performing, you end up with the ideal pop star.”

Not long after Lisztomania, Europe and America were swept by Lindomania — also known as the Jenny Lind Craze. A Scandinavian native known as “The Swedish Nightingale,” Lind won a feverish following with her concerts in London in 1847. The soprano’s voice was so striking that The Illustrated London News declared: “It is as though we now learned, for the first time, what singing really is.”

The legendary showman P.T. Barnum organized and promoted Lind’s 1850-52 tour of the United States, building hype with a relentless promotional campaign. At a time when people had no way of hearing music other than having it played in person — and photographs were still a rare sight — the American public got swept up in the excitement manufactured by Barnum.

When Lind’s ship arrived in New York, the piers and nearby streets were filled with people eager to catch a glimpse of her. A crowd of twenty thousand camped all night in the street outside her hotel. After she performed at New York’s Castle Garden, a newspaper reported, “The audience were thrown into a frenzy of excitement, and cheered with a vehemence such as we have never witnessed at a concert. The orchestra stood aghast, the ladies waved their handkerchiefs, and the gentlemen their hats, convulsively.” After an encore, “women turned pale with intense excitement, and men started to their feet in the most frantic manner, while others might be heard exclaiming, ‘Oh, God!’”

Known for her wholesome image, Lind won acclaim for donating money to charities. Still, Jenny Lind merchandise — including bonnets, shawls, pianos, cigars and cocktails — capitalized on her popularity as she toured America. It was said that her voice was bright and penetrating, but some critics felt she lacked emotional depth. A congressman from Indiana described her as “nothing more than a very modest, tolerable good looking woman.” But she projected a quality of youthful innocence when she sang. As a minister observed, “It is hard to describe her. She looked as if she had just stepped down out of a poem.”

Some four decades after America fell in love with Lind, the country — or at least, its women — came down with a bad case of Paddymania. Ignacy Jan Paderewski’s concerts in the United States were virtually filled with women and girls. One critic who attended one of these performances — a man — said, “There I was, simply girled in! A huge and dominant gynarchy seethed around me.”

A New York World reporter who went to several Paderewski concerts in 1895 sensed “a mysterious current” in the room — “as though an invisible force had united Paderewski and his feminine adorers.” According to the World, one young woman remarked: “Do you know how the lost soul must feel? I do. … When I feel the sensuous throb of Paderewski’s heart, my nature so responds that I feel distance does not separate us. I feel my heart beating in rhythm with his. I feel all control is gone, that I rejoice in the abandonment. I feel that I am absolutely and wholly his. It is awful, but it is a grand sensation.” The World quoted another woman as saying, “He makes my heart stand still, my blood to flow from my heart as he wills it; he sets me on fire; he chills me. He is my master.”

It’s not clear from press reports how much noise these crowds made while Paderewski was actually playing. At a 1901 concert in Poughkeepsie, New York, the audience apparently stayed quiet long enough to hear most of the master’s performance at the piano, until one excited Vassar student screamed loudly just as Paderewski reached the climax of a Liszt composition.

In the face of such adoration, Paderewksi showed signs of strain. He was seen nervously pacing his hotel room. Paderewski’s manager said the pianist was bored by hysterical audiences. Or as one headline put it: “ADULATION MAKES PADEREWSKI SICK.” According to another report, Paderewski’s concert experiences had left him with a phobia of women. Paderewski once told a reporter about the “unpleasant feeling” he got from “annoyances” at concert halls. “These were the result, I suppose, of a peculiar mental state which all musicians know affects women of excitable temperament when they hear music,” he said.

Critics praised Paderewski’s virtuosity, but newspapers were appalled and mystified by the female adoration he inspired. He is “not exactly an Apollo,” the World observed.

“To the eye there is nothing about him to make the pulse beat quicker,” the Chicago Daily Tribune noted, “yet women are spellbound in his presence, go mad in rapture over him, become hysterical and sigh, sob, and clinch their hands in nervous emotion. There seems to be no limit, no measure, to this feminine delirium.” Some newspapers suggested that Paderewski must have a hypnotic power.

His music was at least part of the reason audiences went wild, of course. The World’s reporter believed that Paderewski’s music was causing hysteria because so many of his audience members were “devoid of musical tastes, perceptions and training.” In that reporter’s view, people without musical training were incapable of appreciating “melodious harmonies,” but they did feel music’s emotional effect in the vibrations of their nerves. “Certain notes upon string instruments will so work upon the nerves of brute creatures that they will utter peculiar cries and yelps.”

The Tribune speculated that the women at Paderewski concerts imagined they were looking at “the ideal man” when they gazed upon this pianist. “Paderewski’s adorers … surrender themselves absolutely to the music and revel in all the emotions and sensations that their over-stimulated imagination urges upon them,” the newspaper editorialized.

In his 1982 biography Paderewski, Adam Zamokysi writes: “The sexual element in Paderewski’s success was, of course, exploited to the hilt. From the start there had been, as with Liszt and Paganini, serious over-reaction on the part of women to his playing, and it was reported with glee.”

And what of today’s classical musicians? Do any of them inspire reactions anything like the scenes at a Paderewski concert in the 1890s? “Such responses now seem mainly to be the reserve of pop music,” says Hamilton. Part of the reason for that, he says, is the change in concert etiquette. While outbursts were acceptable at a piano concert in Liszt’s time, they would be considered the height of rude behavior at a classical concert today.

But that doesn’t mean classical audiences can’t respond with tremendous enthusiasm after the final note sounds. Many performers, including Vladimir Horowitz and Van Cliburn, prompted tumultuous applause in the twentieth century, even if they didn’t have girls screaming in the middle of their performances. Media coverage and publicity campaigns rarely catapult today’s classical musicians to the same levels of recognition as they do pop singers or movie stars, but Chinese pianist Lang Lang seems to be maintaining a rock-star appeal.

Some have criticized Lang for being too showy, but his performance style is clearly part of why audiences respond so enthusiastically. Lang’s breakthrough came in 1999 at the age of sixteen, when he was a last-minute substitute for Andre Watts at the Ravinia Festival near Chicago. In his memoir, Lang recalls what happened after he finished Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto: “When I struck the last note, there was a silence, then an explosion. A jolt. ‘An electrical charge,’ one of the critics called it. And suddenly thirty thousand people leaped to their feet. From the stage, it felt to me as if all thirty thousand people were shouting ‘Bravo! Bravo! Bravo!’ It was the moment of a lifetime.”

Welz Kauffman, president and CEO of Ravinia, says another performance stands out in his memory for the way it electrified the audience. In 2008, the Siberian-born pianist Denis Matsuev played music by Rachmaninoff and others at Ravinia’s Martin Theatre. “People leapt to their feet,” Kauffman recalls. “They were applauding as he hit the last note. And they were exclaiming — not just bravos, but gasps and even a little bit of laughter, recognizing that what they’d just witnessed was so pyrotechnically thrilling. They’d never seen anything like it before and they may never see it again. It was one of those moments. I get shivers thinking about it. … I’ve been fortunate to hear many great pianists. This was just something else.”

Robert J. Zatorre, a professor at the Montreal Neurological Institute who studies the effects of music on the brain, says these manias may not have all that much to do with music. Liszt, Lind and Paderewski “all had some kind of interesting charisma, and perhaps music was their vehicle,” Zatorre says. “But there are plenty of nonmusical examples of people with amazing charisma able to make people behave in all manner of strange ways. … Think of football hooligans, political rallies and so forth.”

But Hamilton insists music must be part of the success of Lisztomania, Lindomania, Paddymania, Beatlemania and similar crazes. “Performing isn’t just about playing a piece of music,” he says. “It’s about communication between human beings. … There’s no doubt that a lot of the hysteria, once started, fed upon itself, like the crazy reaction to the Beatles in the early 1960s. Human capacity for self-delusion is almost infinite. But even with their charismatic appearances, Liszt and Paderewski couldn’t have had such an impact if their playing hadn’t been something special.”