This article by Robert Loerzel was originally published in the December 2009 issue of North Shore Magazine.

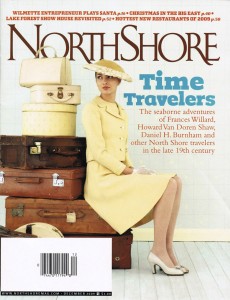

They boarded grand 19th-century steamships in their finery — well-heeled men and women embarking on what promised to be the adventure of a lifetime. What they saw abroad would inspire them and, in a few cases, would ultimately change the political, cultural and architectural landscape of Chicago and its North Shore.

WHEN FRANCES WILLARD TURNED 30 on Sept. 28, 1869, a grand tour of Europe had landed the adventuress and her steamer trunk in Genoa, Italy. The Evanston schoolteacher had been traveling the continent a year and a half already, first by steamship and then by train — and would continue her study of the Old World’s “high culture” for another year.

Willard’s journey with fellow teacher Kate Jackson (whose wealthy family bankrolled their two-year-long adventure) came at the dawn of a golden age of pleasure travel, an era when intrepid explorers boarded large steam ships to cross the Atlantic and see parts of the world they had only read about in books. In some ways, it was the American elite’s attempt to mimic the English, who believed that a “Grand Tour of the Continent” was essential education for those in the upper class. The notion of seeing the world was romantic and glamorous, but getting there was hardly luxurious. Willard’s transatlantic voyage took 12 days, and she was seasick the whole time.

However, once she arrived, and began to see the European cities, art and artifacts she had once only dreamed of, Frances Willard slowly began to discover the woman she would one day become.

Writing in her diary on her birthday, Willard was invigorated from seeing Italy’s treasures of art and architecture. “I was never braver for the future,” she wrote. But when she went to Rome a month later, Willard felt oppressed by the sight of so many poor people begging on the city’s streets. After two months in Rome, she wrote in her diary, “The world seems so sadly out of joint; ‘the cry of the human’ sounds so wailingly in my ears…” Willard began to feel the need to change the world. As she recalled later in her memoirs, “I never dreamed in those lethargic years at home, what a wide world it is, and how full of misery … Rome caught me an intense love and tender pity for my race.”

In Damascus, a tour guide took Willard up a set of rickety stairs to a slave market, where “several miserable negro women, tattered boys and one pretty Circassian girl” were penned up, waiting to be sold. “They hold out their hands for alms,” she wrote in her diary. “Some are in bed, sick in body or in heart. It is a sad sight to behold, in some regards the saddest upon which I ever gazed.”

In Egypt Willard saw women toiling to build a railway embankment, their backs lashed by all overseer’s whip. She described a woman in a black robe walking through the desert with a baby on her shoulder: “If we come near enough, the sight of that dusky face, into which the misery of centuries seems crowded, will smite us like a blow.”

And then, after two years abroad, Willard went back home to Evanston and began drawing from those experiences as she began lecturing about the plight of women around the world. Soon, she found herself in demand as a speaker. In the decades that followed, Willard became one of America’s most famous women, leading the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and crusading to ban alcohol, campaigning for women to receive the right to vote and later waging her battles on a global scale, advocating a “universal federation” that would bring peace to the world.

When Willard made her trip 140 years ago, historians estimate that only one out of every 1,100 Americans traveled overseas each year. While actual statistics are hard to come by, there is little doubt that other North Shore residents were among these fortunate few able to indulge in such an adventure.

“North Shore people would have been exactly the sort who’d make extended visits to Europe, perhaps while at university, perhaps on honeymoon, perhaps while exploring the Bohemian side of their personality while trying to write or paint on Paris’ Left Bank,” says John K. Walton, who edits The Journal of Tourism History.

Like Willard, many of these late-19th-century and early-20th-cenmry travelers brought back ideas, culture and philosophies that changed their lives forever. In some cases, those ideas and philosophies changed the North Shore, too.

Another prominent North Shore resident also traveled to Europe in the late-19th and early-20th century, bringing back influences that remain with us today. Between 1892 and 1893, architect Howard Van Doren Shaw made his first voyage, gleaning ideas from designers such as Charles Rennie Mackintosh of Glasgow, who was combining new elements with traditional forms.

“This type of extended sojourn to see the great art and architecture of the world was common among artists and architects at the time,” writes Shaw biographer Virginia A. Green. “Shaw spent his days sketching buildings and making notes about proportions and colors.”

Inspired by what he’d seen, Shaw built a country estate in Lake Forest called Ragdale in 1898. And Shaw continued to draw inspiration from his travels in 1913, when he visited Paris, Copenhagen, Prague, Vienna, Budapest and various German towns. Shaw’s sightseeing influenced the work he did on Lake Forest’s famous square. “The style of Market Square is a delightful amalgam of European vernacular motifs, planned to re-create the feeling of a village that has grown over the centuries,” Green writes in her book.

And then there’s the story of Evanston architect Daniel H. Burnham and Lake Forest architect Edward H. Bennett, who drew heavily on inspiration from overseas travels when they wrote their famous Plan of Chicago in 1909.

Visiting London in November 1908, Burnham wrote to Bennett: “The Chicago work is seldom out of mind and I feel more and more confident of it as I go about over here. There were has been such a thorough plan as we have for Chicago. But it will take 50 years to make such a solid town as London, even after we have the street layout adopted.” The following month in Italy, even as Burnham commented that Rome was the loveliest city he had ever seen, he wrote: “As we look back on Chicago, its vital quality looms up in the mind. There is where things are to be done.”

Bennett’s family donated these letters in 2008 to Lake Forest College’s library, along with more than 1,500 photographs that the architect used while he was working on Plan of Chicago. Many of these pictures showed Old World architecture. Bennett’s work was shaped by his experiences as a student in Paris. He had also toured the Mediterranean in 1902, and he would visit Egypt in 1910. Bennett was not just Burnham’s co-author on Plan of Chicago — he also worked on zoning plan for Winnetka and Lake Forest.

“Wealthy Chicagoans returned from Europe and wanted their houses and gardens to reflect the aristocratic and upper middle-class homes there,” says Arthur H. Miller, archivist and librarian for special collections at Lake Forest College.

“The Lake Forest places on maple grounds reflected European styles in houses and formal gardens, circa the 1890s to 1930s. These yielded to Art Deco in the 1930s and to International Style in the 1950s. But the post-Puritan generation here built in the mode of what they had seen in their travels for homes and institutions.”

On a trip to Europe in 1926 and 1927, another local architect, Henry Dubin, met the legendary Le Corbusier. Until then, Dubin had designed houses in the English Tudor style. “That changed his whole idea about architecture,” his son, Arthur Dubin, said in an interview. “He built a new modern house in Ravinia, and it was not easy to build it. They not only disliked the modern architecture but the fact that it was designed by a Jewish architect made them even more unhappy.”

Arthur Dubin, who lived most of his life in Highland Park and now lives in Northbrook, became an architect himself. In 1949, he sailed to Europe and retraced his father’s footsteps, looking at buildings designed by Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe. He sketched what he saw and sent postcards home.

“We tramped over Versailles from beginning to end,” he wrote. “It is a disgustingly grand palace. No wonder that the people finally decided to change things. The best part of the visit, like lots of other things here, was that it is just like the architecture history books say — except that now I have touched it myself.”

But architectural ideas were not the only concepts that travelers carried home to the North Shore. Golf was practically unknown in the United States when Lake Forest author Hobart Chatfield-Taylor returned from a trip to Scotland in 1892 with a set of clubs. A year later, he helped to create one of the area’s first golf courses, with seven holes near a bluff in Lake Forest.

Reading through the travel diaries, letters and books of North Shore residents, you can get a sense of what it was like to go abroad in the years before airlines made it easy. People passed the time on transatlantic ships by dancing, playing games, reading books and writing letters, but the most popular activity may have been socializing with other passengers.

Sailing in 1910 on the R.M.S. Mauretania (sister ship of the ill-fated Lusitania), Lake Forest schools superintendent John E. Baggett wrote that he was shy about striking up conversations with strangers. But he did enjoy the simple act of observing other human beings. “How queer many of them (us) are! Of how many kinds!” he wrote.

As two unmarried sisters from Winnetka, Mary and Beatrice Williams, crossed the ocean in 1928 aboard the R.M.S. Ausonia, Mary wrote in her diary: “I am having quite a flirtation with the head waiter. (I would!) He even told me his name this morning.” Later, she added: “I love this life. I never would have believed I could enjoy it so. … I like this little boat a lot. It would be better if there were not five girls for every man.”

Some North Shore tourists traveled abroad in search of romance — or, in any case, romance found them. And what better place to look for romance than Europe’s glittering ballrooms? Getting into a court ball was no easy task, but Cissy Patterson managed it. Patterson, who spent much of her youth in Lake Forest, was a member of the Patterson-McCormick clan that included Chicago Tribune publishers and editors. In 1902, when Cissy was 17 years old, she went along when her uncle, Robert S. McCormick, became the U.S. ambassador to Austria-Hungary. “Vienna is the prettiest, gayest, most frivolous place one could imagine,” she wrote in a letter. Later that year, Ambassador McCormick was transferred to Russia, and Patterson went there, too. A Chicago newspaper reported she “was having the time of her life in St. Petersburg with dances and dinners, wonderful fancy dress balls, suppers and wondrously brilliant court entertainments at the most sumptuous court in the world.”

At one of these dances, Patterson fell in love with Count Josef Gizycki, who had a reputation for womanizing. They got married in 1904, but the relationship quickly went sour. Gizycki’s “castle” in Ukraine was less romantic than his descriptions of it. “It was old and ramshackle and stood in the middle of a little village full of peasants’ huts,” Patterson later testified. “It was five miles from a railroad and almost entirely without modern improvements of any kind.” Patterson said her husband was cruel and unloving. After giving birth to a daughter, Patterson fled with the girl, Leonora. The count sent three henchmen to London to kidnap his daughter. He finally turned the girl back over to her mother when President William Howard Taft intervened by writing a letter to Czar Nicholas II. Patterson returned to Lake Forest, as her divorce case stretched on for thirteen years. Her fairytale romance did not have a happy ending — but Patterson bounced back in other ways. She later became the publisher of the Washington Times-Herald, and her journalistic scoops included an interview with Al Capone.

Some of the North Shore’s travelers were more like adventurers than tourists, trekking to exotic corners of the globe in search of scientific data or just a thrill.

Henry M. Bannister of Evanston and Robert Kennicott, who grew up at the Grove (now part of Glenview), went to Alaska in 1865 — back when Alaska was still foreign land. They were part of a Western Union Telegraph expedition exploring the Russian territory. Kennicott died of a heart attack while taking compass readings in the wilderness. An Eskimo rescued Bannister when he got lost in a snowstorm, after falling behind his companions and their dog sled. “I remember thawing my nose nine times and my cheeks several times but at the tenth trial Jack Frost got the best of me, and … no amount of rubbing or blowing the blood into my face would bring out the frost,” Bannister wrote to his parents. Bannister shared his observations about Alaska with officials in Washington, helping to persuade them in 1867 that the United States should purchase the territory from Russia.

Frances Willard’s nephew, Frank Willard of Evanston, spent years traveling in downtrodden disguises, hanging out with tramps and thieves in both the United States and Europe. Using the pen name Josiah Flynt, he wrote the book Tramping With Tramps. “Flynt” mocked American tourists for showing so little concern about the present-day conditions of the foreign countries they visited. “Americans flock to Europe in thousands, going feverishly from place to place as if their very lives depended on seeing such trifles as the old snuff-boxes of ancient celebrities,” he said.

Flynt stopped at the Munich home of playwright Henrik Ibsen and the Russian estate of Leo Tolstoy, where he ended up staying for 10 days. When Flynt talked about traveling with tramps, Tolstoy stroked his white beard and gazed dreamily at a chessboard. “If I were younger, I should like to make a tramp trip with you here in Russia,” Tolstoy murmured. “Years ago I used to wander about among them a good deal. Now, I am too old — too old.” (Flynt drank himself to death in 1907, according to his friend, Arthur Symons. “I have never met any one in whom the actual love of the road is so strong as it was in Flynt,” Symons said.)

William Montgomery McGovern, who began teaching political science at Northwestern University in 1929, had disguised himself as a “coolie” seven years earlier, sneaking into Tibet, where foreigners were forbidden. He traversed mountains to the capital, Lhasa, where he revealed his identity to Tibetan officials and met with the Dalai Lama. “He was a man who obviously was accustomed to be regarded as a god, and who, moreover, had a firm belief in his own divinity, and yet there was a great quietness, even modesty, about his manner,” McGovern wrote in his book To Lhasa in Disguise.

McGovern explored the upper Amazon basin in 1926, writing about his experiences in Jungle Paths and Inca Ruins. After joining the Northwestern faculty and moving to Evanston, he went to Turkey and Eastern Europe to collect items for Chicago’s 1933 World’s Fair. He also took some time off from teaching in 1937-38 to cover the war between China and Japan for the Chicago Times.

“He only traveled when somebody paid him, because professors in those days didn’t earn a lot of money,” says his daughter, Carol Cerf, who lives now in Massachusetts. With his amazing adventures, McGovern was a popular lecturer at Northwestern.

“He enjoyed being a character, and he loved telling stories,” Cerf says. He wasn’t driven by a desire just to travel, she says. “It wasn’t to see the world — it was to understand it, to explore it. He was curious.” And although McGovern braved the jungles of South America and crossed rickety rope bridges in the Himalayas, he hated flying in airplanes. “My father did everything he could to avoid it,” Cerf says.

The North Shore’s champion tourist from the pre-airline era may have been Anita Willets-Burnham of Winnetka. She did not go more miles than everyone else, but she sure knew how to get around on a tight budget, sketching and painting pictures wherever she went. After seeing Europe with her husband and four children in 1921-22 and then taking the same clan around the world in 1928-30, she chronicled their adventures in the book Round the World on a Penny.

On their first trip to Europe, their children ranged from nine months to 13 years old. On their second trip, they crossed the Pacific and made their way from Japan through China and India to the Middle East and Europe. They made their trips affordable by renting out their home in Winnetka while they were away. They learned how to find inexpensive lodging and split meals for five among the six of them. Willets-Burnham said the family’s expenses during their circumnavigation came to $2 a day per person.

Willets-Burnham’s advice for travelers included these tips: Wear a cape. “What is worn under a cape is nobody’s business.” Learn how to communicate through gestures. “I turned actress, and felt like a lady with a hundred faces.” Don’t be afraid of losing your way. “If you want to see a city properly, get lost in it.” Bring art supplies. “A paint box — a remedy for nerves, a substitute for adjectives.” Travel light. “Even the burden of one suitcase disturbed me. Why be a human truck horse?” And bring along your children. “Families are assets, and if you take one along you are always home.”

Willets-Burnham came out of her journeys with a feeling of warmth toward the rest of the human race. “Travel does something to you,” she wrote. “It has made me feel that the world is mine; I love it all.”