This article by Robert Loerzel originally appeared in Playbill magazine in January 2008.

Are ghosts real? Or do these apparitions spring out of the human psyche? Are they supernatural beings from another world or merely manifestations of our own emotions? Robert Falls, artistic director of the Goodman Theatre, has never seen a ghost, but in directing Conor McPherson’s Shining City this month, he tackles material in which the notion of a phantom plays a key role. A man named John tells his psychotherapist, Ian, that he has seen his wife’s ghost. Real or imagined, John’s experience seems to spring from his feelings of guilt over the way his relationship had been going with his wife before she died in a horrific car accident.

McPherson, whose earlier plays included spooky dramas such as St. Nicholas and The Weir, says he has been drawn to stories about ghosts, vampires and other horrors since he was a child. The spirits in his scripts are both literal and metaphorical. “When people are having a supernatural experience, it always seems to me to be a very lonely experience. It’s a very good useful tool for getting inside a character’s vulnerabilities,” the playwright says.

In 1992, when McPherson was just 21, he introduced himself to Falls, who was in Dublin to direct The Iceman Cometh. In the coming years, as McPherson’s work began to appear on the stage with increasing frequency. (His latest play, The Seafarer, also marks the playwright’s Broadway directorial debut.) “I’m just bowled over by his writing,” says Falls, who earned high praise for this 2006 Broadway production of Shining City. “Often, with very few words, he creates extraordinarily deep characters.”

As a teen, McPherson’s main ambition was actually to play in a rock band, but then he read Glengarry Glen Ross, David Mamet’s quintessential Chicago play. “That really blew my mind,” he says. “I thought, ‘This is like nothing I’ve ever come across before.’ I knew then that I wanted to write a play. It had a huge bearing on me becoming a writer.”

McPherson describes Mamet’s plays in two contradictory ways. On the one hand, he loves how Mamet’s dialogue flows “like a river of thoughts.” On the other hand, he says, “It is very tightly structured and built like a machine.” McPherson set out to accomplish a similar combination of intellectual depth and naturalistic dialogue in his own plays.

Although McPherson has developed his own, distinct voice, Falls still sees some similarities to Mamet. “What they share is the ability to create characters who are struggling toward conversation, who are often bumbling around, finishing each other’s sentences,” he says. “People always say, ‘They’re such naturalistic writers. They have such a good ear for dialogue.’ It isn’t as if David and Conor just transcribe conversation. They take conversation and then they turn it into poetry.” Falls says McPherson, who is now 36, surpassed all his previous plays with Shining City, a drama that seems simple on the surface but has unexpected depths. “He writes with an extraordinary humanity.”

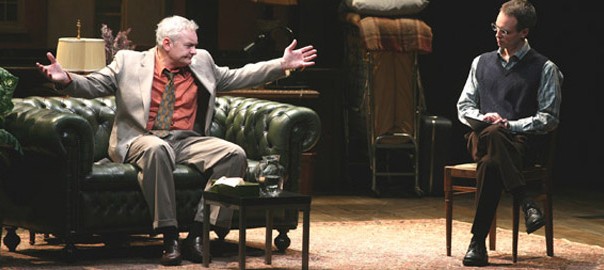

Falls’ 2006 Broadway production of Shining City was nominated for two Tony Awards, including best play. Time magazine, Entertainment Weekly and two New York Times critics, Ben Brantley and Charles Isherwood, included it on their lists of the top-ten plays of year. “In terms of construction, Shining City is as close to perfection as contemporary playwriting gets,” wrote Brantley. The Chicago run of Shining City will feature the same design as the New York production but it will have a new cast, led by Jay Whitaker as Ian and John Judd as John.

When Whitaker read the script before auditioning, he was struck by Ian’s enigmatic nature. Ian is onstage for the entire play, but he barely says anything during the sessions with his patient. At certain points in the play, however, audiences get glimpses into Ian’s private life, revelations that make him appear less sympathetic than he is when he’s merely listening. “I really think the audience is going to see this guy in the moments when I’m not speaking,” Whitaker says, adding that he doesn’t mind playing a character some audience members may end up disliking. “I’ve played a lot of villains, a lot of bad guys,” he says. “I always find something in those people that I love so dearly.”

The ghost story in Scene One was McPherson’s starting point for writing the script. Like the ideas that have sparked his other plays, it popped into McPherson’s head one day. “I don’t have a lot of control over it,” he says. “If an idea just comes into my head, and it stays for a long time, then that’s probably something I’ve got to write. It seems to sort of bake in my head like a cake.” As McPherson expanded that ghost story into a series of psychotherapy sessions between John and Ian, he explored the way men think about women and the way humans deal with loneliness and guilt.

McPherson gave up drinking a few years before he wrote Shining City, and he says his experiences overcoming alcoholism shaped the narrative. “Shining City is a play with a tremendous amount of guilt in it—looking at where drinking had brought me and how badly it made me behave, and how ashamed I was. That play is very much like the morning after. You’ve come through a big fright or a big emotional experience, and you’re standing, trembling in the sunlight.”

Although he shifted from musical ambitions to the theater long ago, McPherson still enjoys writing and performing songs, and he’s a devoted rock fan. The Neil Young and Gene Clark songs featured in Shining City are indications of his musical tastes. “Music is the art form I’m most interested in,” he says. “If I’m not listening to music, I’m reading about music or I’m playing music. It’s my secret world. That’s where my passion is, really.”

McPherson is modest about his musical abilities, calling himself an “enthusiastic amateur.” He doesn’t think he could achieve anything great as a musician, so he tries to write plays that are, in their own way, a sort of music. “You can’t really say what it’s doing to you,” McPherson says, describing the qualities of music he tries to capture with his writing. “It somehow made you feel different and slightly more alive. Something has happened. Exactly what that is, I can’t exactly say. You’re trying to speak to the audience’s soul more than to their mind.”