This article by Robert Loerzel originally appeared in Playbill magazine in April 2012.

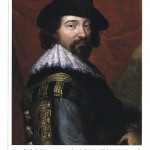

For hundreds of years, people have questioned whether William Shakespeare really wrote the plays we attribute to him. Strangely enough, a Chicago judge ruled on the question in 1916. For a brief time, an official legal decision was on the books in Cook County Circuit Court, declaring that the true author of Shakespeare’s plays was Sir Francis Bacon.

How did the Windy City come to be the venue for this groundbreaking, and possibly dubious, decision? It was all because of George Fabyan, a textile tycoon in Chicago who was obsessed with the theory that Bacon was the true author of the Bard’s scripts — a popular notion at the turn of the 20th century. Fabyan was a large, loud man with some odd obsessions. Riverbank, his 300-acre estate in then rural Geneva, boasted a zoo with bears, alligators, wolves, peacocks and prairie dogs. Pet monkeys scampered around inside his Frank Lloyd Wright-renovated house, where some furniture hung by chains from the ceiling.

Fabyan created a private scientific laboratory at Riverbank, hiring experts to study acoustic reverberations and the effects of the moon on crop growth. “You never get sick of too much knowledge,” he once said. The knowledge-seekers Fabyan brought to Riverbank included Elizabeth Wells Gallup, who said she’d found coded messages hidden inside Shakespeare’s plays. She claimed that the first folio of Shakespeare’s writings used a mix of different typefaces. She isolated the letters in certain fonts, and translated them with a “bilateral cipher” published by Francis Bacon. The words she coaxed from Shakespeare’s scripts seemed to be messages from Bacon himself, one of which appeared to reveal that Bacon was Queen Elizabeth’s secret child. In Richard II, Gallup found this statement: “Men call me Bacon but I am the Queene’s future heyre.”

Fabyan and Gallup believed they has all the proof they needed to discredit William Shakespeare. But William Selig, a Chicago film producer who tapped Shakespeare’s plays for some of his silent pictures, didn’t think so. Selig sued Fabyan in 1916, arguing that Gallup’s research would damage Shakespeare’s reputation — as well as the box-office receipts for Selig’s films. Cook County Judge Richard Tuthill ruled in favor of Fabyan, asserting that Shakespeare was “rather an ignorant man” incapable of writing such sophisticated plays. “Bacon was fearful of the effect upon his reputation if it became known he was a bookworm,” Tuthill said. “But he was a friend of Shakespeare, the theater manager, and he longed to try his hand at play writing, a thing he could not consider in his own name. Hence he used Shakespeare’s name as a cloak.” In the wake of Tuthill’s decision, Alderman Frank Klaus proposed changing name of Chicago’s Shakespeare Avenue to Bacon Avenue. “I don’t pretend to be a Shakespearean scholar,” he said, “but, according to Judge Tuthill, Shakesperare has ‘put one over’ for 300 years.”

However, newspapers and academics heaped scorn on Tuthill. “All that I have to say is that such a view is nonsense,” stated one University of Chicago professor. Some people suggested that the whole lawsuit was a sham, designed to generate publicity for Selig’s movies. The county’s chief judge questioned whether Tuthill had any legal authority to rule on the case. Under pressure, Tuthill rescinded his ruling. As he walked out of the courthouse, he muttered, “The mountains labored and brought forth a ridiculous mouse.”

But that wasn’t the end of the story. All of that research about secret codes in Shakespeare kick-started the field of cryptology. Eighty U.S. Army officers came to Riverbank in 1917 and learned how to decipher secret messages sent by spies and foreign countries. William and Elizebeth Friedman, who began their cryptology careers working with Gallup on those Shakespeare manuscripts at Riverbank, ended up decoding enemy communications for the U.S. military in World War I and World War II. In 1955, the married couple decided to take another look at Shakespeare. And now they saw where Gallup went wrong. Those different fonts Gallup had seen in the first folio? Those were just haphazard differences caused by primitive printing technology. No pattern at all. No secret messages from Francis Bacon or anyone else. Gallup had just found what she wanted to find.

The Folger Shakespeare Library gave the Friedmans a prize for debunking Gallup’s theories. When the Friedmans published a book with their findings, they couldn’t resist including a secret code of their own. If you isolate certain italicized letters in the book and translate them with Bacon’s bilateral cipher, you’ll receive this message: “I did not write the plays. F. Bacon.”